Aquaserge, "C'est pas tout mais"

They are pretty much all Mondays now.

It’s Monday, it’s cold, people who should know better have opinions on the Grammys that they are still tossing around and everything continues to be terrible. I wish I had a way to make your mood a little brighter but I do not. We’re just going to have to get used to things sucking for a long, long time, is the news from here.

A friend heard this one on the radio — which is still a thing people listen to, I guess — over the weekend and passed it along, and I am going to do the same. If you miss Stereolab then maybe this morning will be a little less terrible for you. Enjoy.

New York City, February 9, 2017

★★★★★ To uncorrected eyes, the gray out the window and the spots on the glass made it seem possible that the convergence of forces in the overnight forecast had come out misaligned. But the spots were ice and the gray was driven snowflakes, and everything predicted was happening. There was no reason not to fall back asleep until the children came in demanding breakfast. Already by then there were drifts on the concrete lip at the top of the next building. The flakes filled the avenue. Sometimes the view seemed to clear but it was just that the flakes had become tiny and hard to see. The wind rattled like a sheet of paper. By afternoon there were actual pauses, but the snow came back in bigger flakes. At last the end of it really came. Light came from the west and the clouds grew lustrous as the five-year-old began packing snowballs. The top snow was too dry and crunchy to hold together, but the deeper layers compacted easily enough. The five-year-old set up two or three yards off and hurled his missiles. From the southern position, to return fire, all it took was a handful of the loose snow lofted into the wind. A gust pulled down a curtain of snow from the scaffolding. Stubby icicles had been bent into pointing uptown. Snow inside a glove could be borne well enough, but a bare hand snapping camera photos burned in the frigid air. A toddler in a stroller rolled into the elevator, its cheeks true apple-red from the cold and swollen from grinning.

Things I Read This Week And Liked

Friday reading roundup

The morning after the show I attended, they woke up together, ordered “four hundred thousand dollars’ ” worth of room service, and experienced a moment of gratitude over being in a hotel room. “We’re both deeply romantic about hotel rooms. We’re, like, ‘This linen!’ ”

Kate Berlant and John Early’s Escape from Comic Realism

Experienced as the exception, leaks promise a rare glimpse of unfiltered, unauthorized truth. As the rule, uncertainty will prevail. Politics documented by leaks and politics enacted through leaks are two very different things — and from the outside, the second is indistinguishable from the first.

The Media’s Risky Love Affair With Leaks

When the real world is a nightmare and the former theoretical utopia of the internet is another one, it’s necessary to imagine what other kinds of utopias might look and sound like.

Album Review: MUNA Imagine A World Ruled By Empathy

(I was allowed inside swiftly, of course, with the mere mention of my name and my outlet and the spelling of my last name and the spelling of my last name again — I don’t mean to brag.)

Drinking Wine and Dropping Snacks Near Emily Ratajkowski at InStyle’s FW Party

Whitney was the first pop star who I knew was a pop star, because I heard my mother singing her music in the house when I was a child. This was my sole marker for what a popular musician was: any musician who made my mother happy enough to lend her voice to a brief opportunity for harmony.

Whitney Houston Was Too Perfect To Stay

Mm, clicky: Grey Gardens is for sale | After years-long baboon battle at Toronto Zoo, new queen finally emerges | A new amoeba that looks like a wizard hat 🙂 | Patti vs Aretha

Carrying Around My Shit

The diary of a Muslim immigrant in New York

Monday

I get to work at 7:30 a.m. so that I can go to the bank nearby. I want to ask about whether I would be able to transfer my savings out of the country if I’m forced to leave. The woman behind the counter looks at me like I’m crazy. The video camera on the counter looks at me like I’m dangerous.

After work I go to see my friend. She has two wonderful daughters, both engrossed in a cartoon on the TV when I arrive. I sit behind the couch to watch along, and the younger of the two slides off the couch and tiptoes around it towards me. She’s three years old and has a grin that completely disarms you. She’s offering me one right now — her little teeth perfectly alternate with gummy spaces. Her face doesn’t smile because she’s joyful, she seems to be joyful because she’s smiling. Lately, she has started asking people “are you ha-pee?” It’s a hard question to answer honestly (and it’s hard to lie to a child).

Tuesday

There is a problem with my visa. I went back to London over the holidays and when I re-entered America in January, border control wrote the wrong date of expiry when processing my visa. It’s supposed to run out next year, but they wrote February 14, 2017 for some reason. If HR hadn’t spotted the mistake in my electronic records, I would have become an unauthorized immigrant overnight. An illegal, without even knowing it.

I was advised to leave the country and re-enter showing the paperwork that proves I’m allowed to stay here long after February 14 but I’m too scared to leave in case I can’t get back in. I call a friend who tells me to call a lawyer for advice. I find one, and she advises me over the phone to stay put. She explains that travelling is a really bad idea right now; I should try to get the error fixed from where I am. She describes clients who have no attachment whatsoever to the seven countries affected by the ban but who are being detained nonetheless. The lawyer tells me to try calling a number tomorrow to schedule an appointment.

Her voice croaks as she is about to hang up the phone, she sounds like she is crying as she says “I was lucky to be born here.”

Wednesday

I call the number at 9:02 a.m., two minutes after the office has opened. An immigration officer with a Hispanic last name fixes my problem by 9:05 a.m. and wishes me a good day. I sit in the office meeting room until 9:10 a.m. trying to make sense of it all.

I’m allowed to stay after February 14.

Elle magazine have approached me to be on a list of single people that they are curating for Valentine’s day. They send me a short questionnaire to accompany my photograph. I respond to the questions like “What would be your tagline on Real Housewives?” with answers like “Financial independence is freedom.” I wonder if they’ll publish it.

Thursday

I go to see the lawyer who helped me on Tuesday. My future in this country could depend on this woman, so I need her to like me so I think about what clothes to wear and how much makeup to put on. She didn’t ask me for a cent for the call on Tuesday. I take flowers.

We talk in the ground floor of her beautiful Brooklyn home. She asks me whether I have dual nationality, where I have travelled to recently, what kind of visa I have and who vouched for me first time around. She asks whether I have an American boyfriend and I say “no, I don’t want a green card that way anyway”. She responds with another question:

“How tall are you?”

“Uhm, five-four, five-five I guess”

“You would be perfect for my son.”

She shows me family photos on the shelf, “That’s him.” “Oh,” I reply “he’s cute. Is that him in that one?” “No,” she frowns, “that’s me.” I feel terrible.

Her grandfather escaped the Nazis she explains, so she understands how being different can make you feared by others and that, ironically, that can make you fearful too. She gives me a big hug as she sends me out the door and says she wants to do anything she can to help me. I want to get her more flowers.

Friday

If you’re easily repulsed you might want to skip these next two paragraphs. My gastroenterologist told me to collect three days’ worth of stool samples so I have duly done so. I have to give them to the lab today but, holy hell, I also have to go to court first thing in the morning after being given a summons. While filming a video series, my crew and I walked on what we thought were disused railway tracks. Two police officers discovered our four-person film crew and, after chewing on their pens a bit and conceding that there were no signs to tell us the tracks were active, decided to issue us with tickets all the same.

Should I go to the courthouse, wandering through the metal detectors and appear before the judge with these plastic containers of my excrement? Or should I go to the lab first and risk being late to my first (and please, God, only) court appearance. I text my friend to ask her advice and she replies “who the f**k decided to call it a stool?” She has a point, albeit an unhelpful one. I decide to try to ditch the poop at the doctor’s office. I rush through the streets thinking how strange it is that no one else but me knows what these bags conceal.

I make it to the court in time and find my friend Mae already there. We watch other defendants filing in as we wait for the court to be in session. There are ten of us in this room, now fifteen, now twenty. It looks like a little chapel — wooden benches sit in rows facing front, divided by a middle aisle for us to walk down to meet the judge.

And then I see him. My heart is pumping so large that it pushes through my back against the wooden seat behind me. “Oh my God, ohmygodohmygodohmygod,” I say to Mae. “Oh my God,” Mae replies. She too has just noticed that the last two defendants to walk into the courtroom include a tall bearded man I haven’t seen in seven months. It’s my ex boyfriend. Turns out he had also been trespassing somewhere in Brooklyn late last year, trying to find a place to skateboard.

He hasn’t seen us and sits on a bench ahead and across the aisle from where we are. Mae rubs my leg and says, “Oh my God” again. Finally, he swivels in his seat to take a look at the courtroom. He sees Mae, his eyebrows raise then he looks to see who she’s with and says “Oh… hey.” I wave awkwardly and we both laugh at how ridiculous the situation is.

We each get an “Adjournment in Contemplation of Dismissal” — it means that the judge doesn’t care whether we’re guilty or not guilty. So long as we don’t get into trouble for the next six months, our cases will be dismissed.

Six months. Immigrants already know that we have to meet an impossibly high standard of citizenship. We have to be more patriotic, more polite, more hard-working. But this ruling makes me extra cautious to keep my head down and never be in the wrong place again. But that means not attending protests, that means not saying “I am here.”

At about 7:30 p.m., those of us who are left in the office hear that a federal judge has halted Trump’s “Muslim ban.” I look at a coworker who can also be described as Muslim (though she doesn’t describe herself that way). We both sigh — it’s good news we won’t get excited about. I notice how a lot of frightened people end optimistic sentences with the words “for now.”

Saturday

I leave my apartment at 8 a.m. to work on a series of data visualizations for Black History Month and don’t get back until 9 p.m. It’s worth it.

Sunday

I work until 5 p.m. when I have to go out for a date. It’s for a Valentine’s Day special of a podcast I’m working on.

There is nothing noteworthy about the date except that there is a producer sitting at the bar behind him with headphones on listening to our conversation. Where normally I am used to listening to a man talking at me about his dog, now I can spot someone in the far-off distance who looks slightly irritated on my behalf. I am used to shrugging when a man who is a musician and photographer explains polling to me (even after I tell him I am a data journalist).

He tells me he was going to vote for Trump but ended up going for a third-party choice instead. I don’t say very much. The producer comes over and says it’s time to wrap up. Would I go and wait in the other room while she asks him a couple of questions?

I haven’t cried all week but my lip quivers as I stand in the side room. The producer walks in and flings her arms open as she says “if I die, I want you to marry my husband and raise my child.” I burst into tears which I bury in her chest.

Mona Chalabi is the Data Editor of Guardian US. You can read her diary from last week here:

A chronicle of fear: seven days as a Muslim immigrant in America | Mona Chalabi

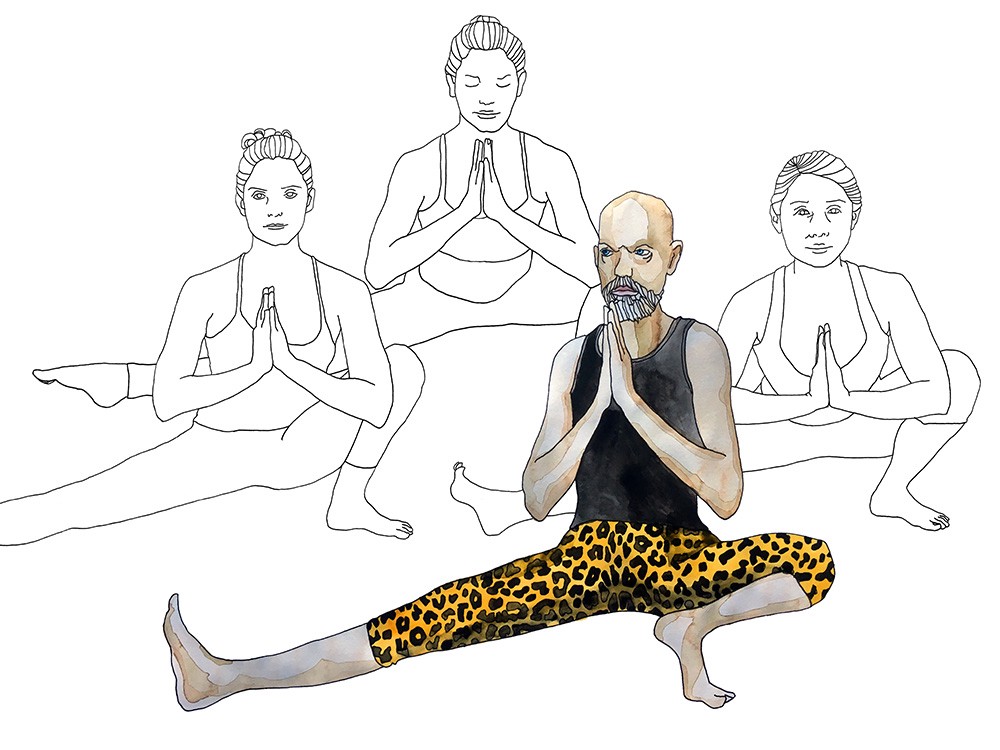

Yoga studio, Greenpoint

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

Oh god what was I doing here, what were we all doing here, in our Active-Wear, “finding a comfortable cross-legged seat” on our “sits bones” and “inhaling for Om” — which, much like the burning of bras to feminism, had always seemed to me more like a hackneyed parody of yoga rather than something people actually did. But here we were, half a dozen men and women obediently closing our eyes and chanting om as a stick of palo santo burned gently in a corner while outside, everywhere, the world truly was, as the parlance went, in flames.

Several hundred strangers yelling their rage and resistance at JFK Terminal 4 had made a mighty noise. I’d shouted my favorite chant, This shit is illegal/ I-LL-E-GAL until it faded and I’d felt a brief disappointment as another rose up in its place. But this, a low reverberation of six strangers’ single syllables, just seemed hysterical. Awfully so. At least the string quartet on the Titanic played more than one note as the ship sunk.

I wondered if thoughts like these were crossing your mind too. I’d recognized you from the class the day before. It would be hard not to, because you were six foot six, leggy, and looked like Michael Stipe, if he were to wear high-gloss, skin-tight leopard print. (He should.) I gave you a smile of recognition when I walked in and it startled you — you shrank back with shyness, which struck me as delightful coming from a fifty-something man in leopard print leggings. Outrageously dressed introverts pierce me straight to a place of tenderness.

Half way through the class, your skinny buttocks were half a meter away from my nose as we squatted wide and lunged low from one foot to the other, our palms in prayer, like ninjas or cossacks. As you launched your haunches to the right there came a modest but definitive fart, a plangent toot sounding out into the quiet. For a second, I was six years old, ambushed with anarchic glee, casting for an eye to catch to share a suppressed giggle. No one blinked, of course. I don’t even know if you were blushing because my only view was your backside. Perhaps you’d achieved the level of yogic equanimity where a fart in class was just cause for a koan. A tree falling in the forest. Except we were around to hear it.

I recalled the way my husband’s delight had verged on mania when I’d told him what “trump” meant in British slang. It made me homesick, not so much for Britain as a place, but for its idiom, where intransitive verb predated incoherent villain. We’d Googled to confirm and the definition we found ended with this generous description: “often in a highly audible way (as in with trailing sound).” What with your resemblance to its frontman, I already had R.E.M on my mind, and now I found myself mentally singing their 1992 single ‘Everybody Hurts,’ except my brain was replacing “hurts” with “trumps.” I enjoyed the rest of the class.

The Harvest Of The Damned

I wonder how Steve Bannon’s screenplay ends

The Daily Beast revealed this week that they’d gotten their hands on an 11-page outline for an unmade movie Steve Bannon was shopping around Hollywood in the spring of 2005. It’s entitled The Singularity: Resistance Is Futile, with an alternate working title of The Harvest of the Damned. Fun!

Steve Bannon Wanted Mel Gibson for His Movie About Nazis, Abortion, ‘Mutants’

The document lists Bannon as a writer, producer, and director of the would-be movie, and divides it into 22 segments the Beast describes as, “A heady, incomplete mix of science, history, religion, and politics.”

It sketches out a story in which mankind’s unquenchable thirst for knowledge and scientific advancement has led to horrific, fascist atrocities and forced sterilization, drawing a direct line between those atrocities and modern bio-technology… The draft is unfinished, so it is unclear precisely what Bannon’s full message and story arc were intended to be. But the theme that genetic and reproductive sciences has led to Nazi horrors and war crimes is a theme seen in a lot of conservative agitprop.

The Beast focuses a lot on plot summary. Over the course of the film, scientists try to perfect the human race—but at what cost? (A: God’s natural order for the world.) Hot topics include “the Enlightenment, Christianity, English literature, physics, nanotechnology, genetic engineering, and ‘incomprehensible social change’” and there’s a lot of Hitler material in there too. I highly recommend you check out the excerpts they have.

What really piqued my interest, though, is the fact that the outline has no ending. The second-to-last section of the movie is described as “post-humanity,” where “The New Immortals” seem to be “living happily… ever-after” in a society that touts “spare body parts for sale.” Exciting. Can’t wait to see what’s at the finish line for these people.

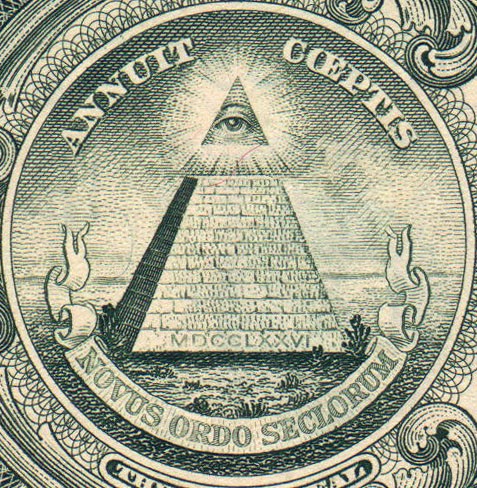

The final section, though, is much less detailed. It’s entitled “THE SINGULARITY,” and allots four-minutes for only the following description: NOVUS ORDO SECULORUM. It’s an apparent variant of the Latin motto we print beneath the pyramid on the American one-dollar bill, and translates to “New Order of the Ages.” Would be cool to know what that… entailed, Steve. Purely for art reasons. Not fear ones.

No one seems to be able to get a hold of Bannon for comment, though. His former writing partner confirmed that the project was “unfinished” and also said she can’t remember the contents of the outline, but something tells me they brainstormed some endings. And that their specifics—or at least their cultural overtones—may come up in conversation sometime over the next four (lol) years. It would be cool if we could look into them now.

Anyway, I have reached out to our president’s Chief Strategist for comment and will update this post as soon as he gets back to me:

@stephenbannon how would ur screenplay have ended?

> Your medal

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

For getting through these last three weeks, you deserve a medal. Maybe a few medals.

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

Eluvium, "Windmills"

Back to reality

Let’s just get right to it: “Disquiet is a benefit compilation of ambient artists, across three volumes, with 100% of the profits going to non-profits that support the environment, investigative journalism, women and minorities.” Pre-order it here or check out the sampler for the first volume here. And here is something absolutely gorgeous from Eluvium, which I hope is not the best part of your day but let’s be honest probably will be. Enjoy.

Three Weeks Later

A reflection in verse

You’d think by now the whole thing would be easier to endure

You’d still be sad and angry, but less frenzied than before

You’d make it through the day without becoming quite so tired

You’d have a conversation where “calm down” was not required

Each time your phone lit up it wouldn’t fill your heart with fear

You wouldn’t frame your plans around the phrase “if we’re still here”

You’d have a decent shot at simply sleeping through the night

You’d feel something other than a permeating blight

Instead you are reminded as each custom is defiled:

The world is being held hostage by a giant fucking child

Nice Chops If You Can Get It

How one of the last segregation-era businesses in Chattanooga, Tennessee struggles to survive urban development

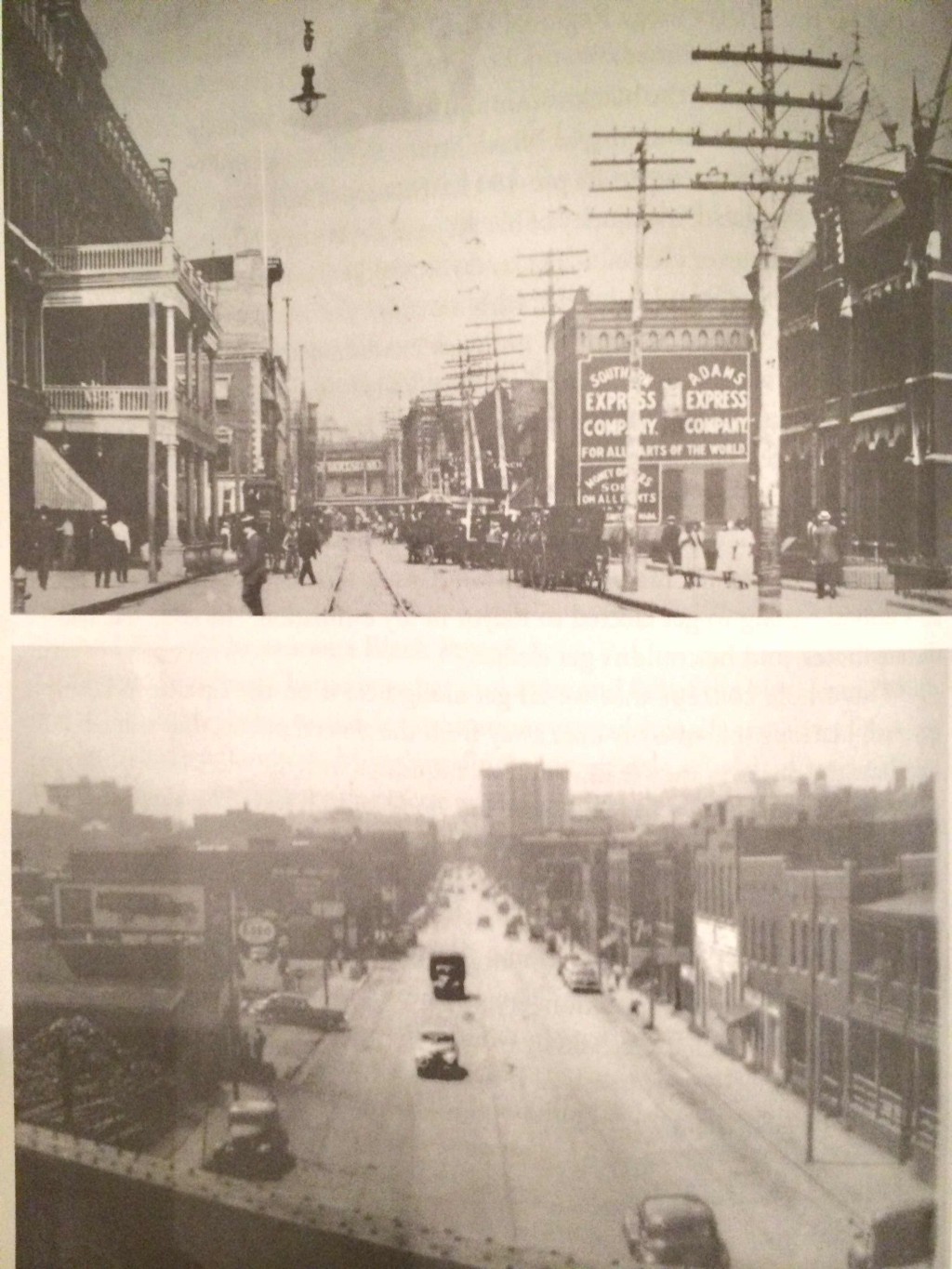

Along the eastern block of Chattanooga’s M. L. King Boulevard, an array of large, colorful murals distracts the eye from a smattering of old, crumbling, graffiti-infested, two-story buildings that desperately cling to a former, much grander life. Before the street’s name was changed in 1982 to honor the slain civil rights leader, it was called Ninth Street, or “The Big Nine,” and it was the epicenter of Chattanooga’s black community.

As a result of segregation, Ninth Street thrived with black-owned movie theaters, grocery stores, night clubs, and countless other businesses for most of the twentieth century. It was also a hotbed for the music scene: Bessie Smith sang on the street corners of the Big Nine as a little a girl; Fred Cash and Sam Gooden played on Ninth Street before forming The Impressions with Curtis Mayfield; same with Jimmy Blanton before Duke Ellington, and Clyde Stubblefield before James Brown. These musicians catapulted the Big Nine to a fame comparable with New Orleans’s Bourbon Street and Memphis’s Beale Street, and even New York’s Harlem; but it was the local musicians who played in clubs and juke joints that elevated the area to its regional fame.

Everyone from Cab Calloway to Jimi Hendrix came to town to play Memorial Auditorium, where until the 1960s blacks were forced to sit in the balconies while the white patrons sat in the better seats on floor level. After their shows, the performers and their bands headed down to Ninth Street to jam with local musicians and house bands who frequented the other venues. After the clubs closed at 3 a.m., everyone would go to down to Memo’s to get their chopped wiener fix. A chopped wiener plate, or “chops” consists of chopped hot dogs covered in a special, secret-recipe chili sauce, served with slaw, a roll and a side of mustard sauce.

Memo’s, a family-owned restaurant open since 1966, is owned and operated by Vic Williams, Jr. and his sister Mona Hammonds, along with their children and grandchildren. Business is steady, with most customers trickling in to get take-out, but it’s far from what it used to be in the heyday of Chattanooga’s music scene. Moses Freeman, a Chattanooga City Councilman, has known the Williams family since 1952 and has been coming to Memo’s for fifty years. Before there was a Memo’s, there was a place called Pit Casaloma’s, Freeman said. When Richard, Vic’s father, bought it, it became a gathering place for those heading out to or coming back from the clubs. “There was a time when Memo’s was hopping, along with the rest of Ninth Street,” he remembered.

Vic Williams, Jr. remembers his father’s first business, an ice-cream store called Frozen Joy. “My dad started working there when he was fourteen. I think by the time he was fifteen, he was manager. So, by the time he finished high school, he got a loan and bought the business.” He then bought another ice-cream shop called Eskimo Joe’s, before finally getting into the chopped wiener business.

Al Hammonds, who married into the Williams family and now works at Memo’s, told me Richard’s wife created the chili sauce for the wieners, and it took off. “She took it to another level. The only thing I can think of is that you can’t get this chili sauce recipe they developed anywhere else.” Hammonds wife and Vic’s sister, Mona, chimed in. “And lots of people try to emulate it, but it’s not the same.” Al was a Memo’s fan well before he married Mona, He was raised on chopped wieners, he said. “Now I can’t get enough. And I work here and still can’t get enough,” he said.

Before it was The Big Nine, it was just Ninth Street. In 1870, John Lovell, the son of a white father and a black mother, set up his business on the street under a tent and sold whiskey and ran a prostitution ring. He eventually earned enough money to build Mahogany Hall, home to Chattanooga’s largest bar and dance club. Another early African-American businessman, E.O. Tade, is regarded as the father of the Ninth Street community, helping to establish a prominent district for blacks to work and socialize in without fear of retribution.

By the turn of the twentieth century, juke joints and bars abounded. Old Crow Place was among the most popular, a place that promoted wrestling matches with a grizzly bear kept in a sawdust pit in the back. But Ninth Street bustled with more than just bars and clubs. Just a few blocks away, Lincoln Park had the first lighted softball field for blacks, and the South’s largest blacks-only swimming pool, thanks to the Works Progress Administration. A teenaged Willie Mays played baseball there as part of the Negro League. Ninth Street was the center of the business district. “It was hustling and bustling,” Councilman Freeman recalled. “We had taxi cabs who ran routes — what we call jitneys — who all brought people here to do business; to buy clothes, to pay rent, to get their hairs fixed, barber shops to get their haircuts, shoe shine parlors.”

“The nightlife was totally something different,” He said. “They operated two and three shifts, day and night because at that time, Chattanooga was a manufacturing town. When one shift got off, they came to Ninth Street. So you have beer vendors open early in the morning to sell breakfast and beer… people would start on one end of the Ninth Street and walk their way to the other end making a lot of bar-hopping, club-popping, and you had a variety of music.”

But starting in the 1950s and continuing for the next two decades, the Westside Renewal Project (or as it was later known, the Golden Gateway Project) dismantled the neighborhood. A product of the Housing Act of 1949, which provided federal funds for cities to buy distressed properties and spawn massive urban renewal projects, it rerouted the new interstate highway routes through Chattanooga. The project forced many of the black-owned businesses of Ninth Street to relocate, and destroyed more than a thousand buildings.

More than sixteen hundred families had to move, forcing the local housing authority to create public housing in other parts of the city. Jeff Pfitzer, program officer for The Benwood Foundation, a non-profit working on revitalization efforts on M. L. King Boulevard, said, ”The wholesale removal of so much — and granted, it was poor-condition housing stock — but the wholesale removal of that much housing stock in an urban environment represented a big displacement of the local population.”

Douglas Turner Day is a folklorist who was commissioned by the Chattanooga’s Allied Arts, the Tennessee Arts Commission, and the National Endowment for the Arts to do a research project to preserve the history of the Big Nine back in the early 1990s. He attributed the loss of businesses and homes of Ninth Street, but the culture as well, to urban renewal, or as he referred to it — borrowing James Baldwin’s line — negro removal. “Those doing the planning and implementation may have had good intentions, but the end result was institutional racism. It may have not been anybody’s intention to try to drive black business people out of doing it but that’s what happened.”

In 1955, the City of Chattanooga authorized changing Ninth Street from a two-way to a one-way road, which meant less traffic running through the area. Williams remembers what this did to Memo’s. “When they made it one way, it almost killed his business because customers were leaving, they weren’t stopping anymore when they were leaving town… And see back then, they just did it. They didn’t have a public forum.” Residents and business owners weren’t included in the city’s decision-making plans.

“The flight of the whites to the suburbs in the past thirty years, followed by the African-American population moving further out killed the downtown,” said Kristy Hunley, Benwood’s program and financial officer. “It happened everywhere, not just M.L.K. The black-owned businesses moved with the population that supported their services. Our downtown department stores moved to the malls.” By the early eighties, the few remaining shops and clubs on Ninth Street had barely enough customers to stay open, but Memo’s survived.

In 1981, many of the city’s black residents wanted to change the name the name of Ninth Street to M. L. King Boulevard, hoping it would spark revitalization efforts in the area. A few white business owners were against the idea, feeling it would be bad for business, but on Jan. 15, 1982, the name change was enacted. In 1986, the Bessie Smith Strut — a free street festival featuring live blues music — began as part of the city’s Riverbend music festival in an effort to drive more traffic to the area. For a while, it worked. Throngs of crowds, black and white, would jam pack on the boulevard, dancing in the street. But in the last few years, crowds have been thinning. The Bessie Smith Hall and Chattanooga African-American Museum opened in the area in 1997 with the promise of other businesses following; they didn’t. The former Big Nine continued to rot.

Between 2002 and 2005, a local organization called M.L.K. Tomorrow incentivized residents and potential home buyers to invest in the neighborhood surrounding M. L. King Boulevard. by helping to fund the construction of new houses and the renovation of old ones. Eventually, a few new businesses sprung up, hoping to take advantage of the expanding student population at the nearby University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, which meant the construction of more dorms creeping closer to the boulevard.

In 2012, local arts organizations began commissioning local artists to paint murals on the buildings on M.L.K. Blvd., acknowledging the area’s vibrant past, something that had been buried for years as the area sank into despair. Among the murals adorned on historic buildings dotted up and down MLK Blvd.. When the AT&T building, formerly the South Central Bell building, was built on Ninth Street in 1973, it looked like a bunker of sorts (To be fair, though, it was built that way in case of catastrophe, so that the city’s phone lines would stay intact). Now, it’s covered in a huge, colorful mural inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Public Art Chattanooga, together with the Benwood and Lyndhurst foundations, commissioned Philadelphia-based muralist Meg Saligman to paint the mural, working with the community to create something that reflected what the Big Nine represents to Chattanooga.

During one of my many visits to Memo’s, Vic told me more about Richard, who died in January, 2016. He told me his father was a strict disciplinarian but he still liked to have fun. He said once, back in the seventies, someone stole several boxes of hot dogs from the restaurant. “The police called and told me that we got your merchandise… that we recovered and we could come down and pick them up. Okay, easy delighted you know? So, when we got down there it was less than what the person said that they had.” His dad didn’t argue and he and Vic took the boxes back to the store. “But the next day we opened, there was a line of police cars lined up, coming in buying hot dogs,” Vic said with a laugh. “I thought that was pretty good.”

A report called “The Unfinished Agenda” was released a couple of years ago by Ken Chilton, a professor at Tennessee State University’s Department of Public Administration. It detailed some alarming statistics about race in Chattanooga. The report says that in the mostly-black neighborhoods of the city, unemployment is staggering, with the average poverty rate at 63.5 percent. It also points out that though urban renewal is a different process now than it was back in the fifties and sixties, the effects are often still the same, with black families being displaced, forced to move to lower income neighborhoods or even public housing, because they often can’t afford the higher property rates.

Back on MLK Blvd., two new breweries have opened up, and another restaurant is in the works. The Camp House, a local coffee shop, moved from it’s location on the Southside to MLK Blvd. to help encourage businesses to move to the district. Student apartments have also been built nearby, a block over from the boulevard. This time, it looks like efforts to revitalize are going to stick. And that’s good economically. But as disappointing as it was to drive through the area when it was neglected, whatever history that was here pertaining to Chattanooga’s African-American community, it looks like is, like everywhere else, slowly being washed away. And as new life is breathed into the Big Nine, Memo’s continues to hang on. But business isn’t what it used to be. In an effort to bring business and music back to the boulevard, Memo’s will begin showcasing live music on the weekends.

As Memo’s celebrates it’s 50th anniversary this month, the Williams family hopes to be a part of the renaissance that seems to be happening all around them. But if the music fails to bring more customers into their restaurant, one of the last of the Big Nine establishments may not be able to survive.

Charles Moss is a writer from Chattanooga, Tennessee. He’s written for The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Slate, and other publications.