Organic Food Makes You A Monster

“These findings reveal that organic foods and morality do share the same conceptual space,” Eskine concludes, adding that the study “suggests that exposure to organic foods helps people affirm their moral identities, and attenuates their desire to be altruistic.”

— Loyola University New Orleans psychologist Kendall Eskine discusses his finding that being around organic foods turns you into a jerk, apparently because you think the organic food makes you extra virtuous. This explains why people who shop regularly at Whole Foods are so insufferable.

Photo by Yuganov Konstantin, via Shutterstock

"You Get On The Internet And Pretty Soon You're Drunk": The Orthodox At Citi Field

“You Get On The Internet And Pretty Soon You’re Drunk”: The Orthodox At Citi Field

by Sean Patrick Cooper

While the ultra-Orthodox steadily streamed down the 7 train platform and onto the pavilion, a group of four teenagers sat around the big red New York Mets apple, waiting for their friends. This was last night, an hour or so before the Citi Field gates opened. Outside the stadium, a few hundred ultra-Orthodox Jewish men stood around, waiting for the masses to arrive to this rally about the dangers of the internet. The 40,000-stadium tickets had sold out the week before and the event organizers — The Union of Communities for the Purity of the Camp — had scrambled to rent nearby Arthur Ashe Stadium for the 10,000 or more attendee spillover. These boys were among the other early arrivals. One of them, tall and skinny, with his wide hat tilted up over his face, came over to speak to me, his words coming out in excited staccato bursts.

“You get on the internet and pretty soon you’re drunk,” he said, as he mimicked a person wobbling back and forth. “You’re drunk on distractions, and you can’t get back to focusing on your studies or to your work or to your family.”

One of the boys took a call on his cellphone from a friend who’d just arrived by bus. The group left to go find him in the parking lot.

“Well, now I don’t know what I’m going to do,” said the boy who stayed behind. “I guess I’ll just wait here for some action.” He wore a thick black coat and rimless glasses. Columns of curls framed his round face on either side like fly traps. He was 16, in his third year of what I would consider high school.

We chatted for a bit, and he explained to me how the internet affects his mind. “I had an iPod touch for a while and it was really bad. I’d go find a bench outside an apartment complex and get on someone’s wi-fi signal, and watch Youtube videos of car chases, cop chases, action movie scenes. Watch them for hours. Then I’d get some video games on there and go home and play them till 3:00 in the morning and be wrecked when I woke up. Just ruined the whole day, my mind all scattered. I couldn’t stop,” he said. “You know, it’s sort of like smoking cigarettes, and when someone asks you, ‘When are you going to quit?’ ‘Well, I’m going to quit when I have this last one.’ But there’s always one more after that last one, and another pack after that. You can’t really quit once you start because you’ll always have one more last one.”

He had bought his iPod Touch from Walmart and recently sold it to a classmate, but still goes with friends who have iPods to sit outside apartment buildings to watch clips on Youtube. Behind us, a barefooted man wearing a leopard-printed toga started jumping up and down. He raised a Fred Flintstone-style club at the passing crowds, and yelled something incomprehensible about not using electricity or cars. He was with a satirical protest group called Cavemen.

“I wish someone would put him back in his dog cage,” the teenage boy said, smiling. “I’m worried he might come over here and bite me.”

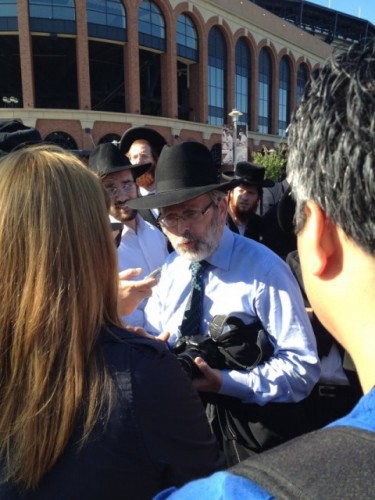

A few minutes later, a group of Orthodox men gathered around a pair of women protestors talking loudly with an older man with a neatly trimmed grey beard. Around them stood media people taking their picture. “Yes, but you don’t seem to understand the thrust of the protest,” the man said.

If the young woman was genuinely confused about the rally’s intent, so too were many of those in attendance. It was widely known the rally was to be about the dangers of the internet, and it was speculated that its speakers would use the rally to define what role the internet should play in the daily lives of the ultra-Orthodox community. But in the weeks leading up to the event, the message from the organizers was mixed. Some were saying that no proper Jewish home should have internet access, and probably not even a computer. Other interviews and statements implied that the internet was okay to use, but only if it were filtered with special software and being used for business.

In a letter to the parents of students enrolled in a Prospect Park Yeshiva, administrators wrote that “they demand that each and every parent attend this special gathering.” Similar letters from other schools floated around the internet in the days leading up to the event. For the women who weren’t allowed to attend — it has been decided shortly after the event was announced that it would be a male-only rally, it being deemed too complicated to divide the stadium into separate gender sections — live video streams were being broadcast to gatherings in Dallas, Chicago, and Detroit, Los Angeles, Cleveland, and Miami, Toronto, Mexico City and as far away as Brazil.

As afternoon closed in, the sky was blue and the sun was warm and there was little humidity in the air. Families, wandering over from Arthur Ashe Park with children in strollers, looked around in confusion and then headed back over the boardwalk bridge. Hundreds of buses were on their way to Citi Field, coming in from the ultra-Orthodox communities of Flatbush, Williamsburg, and Monsey; from Lakewood, New Square, and Kiryas Joel.

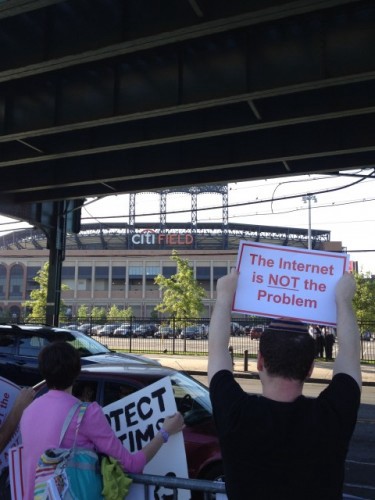

Down the street from the subway platform, the small group of Caveman protestors gathered about fifty feet away from a larger and better organized protest group called The Internet Is Not A Problem. The large group, maybe a hundred strong, was led by Ari Mandel, who had the idea to organize the group after speaking with his friend, Chanie Friedman, both of whom were frustrated at what they saw as a misdirected use of energy by ultra-Orthodox leadership. The greatest threat to the community wasn’t technological, Mandel told me, but rather how the community was addressing cases of sexual abuse of children. He pointed to a pair of recent New York Times articles that exposed a potentially massive problem within the tight-knit Jewish community, wherein victims and their families were being discouraged from, and sometimes even ostracized for, speaking to the police about instances of sexual and physical abuse against their children.

As cars and buses passed by into the parking lot, Mandel and his group held signs with messages like “The Internet Never Molested Me” and shouted sing-song slogans.

“There’s some back and forth here between us and the people in the cars, but there’s no serious dialogue yet,” said Mandel. “Just a few people who’ve come up to us and told us we’re embarrassing ourselves and the community.”

Friedman stood beside Mandel, holding a small sign as she leaned against the metal barricade separating the protestors from the crawling traffic. “They don’t want to understand the consequences of child sexual abuse, of what happens when you’re exposed to that,” she said. “I read on a Yiddish forum someone saying that the whole concept of sexual abuse is made up by the Goyim, the outside world.”

She continued: “There’s this attitude within the community that this is just something that happens. They’ll say, ‘It happened to my father, and to his father, and it’s just no big deal.’ But the focus on the internet is just a distraction from what’s really going on here.”

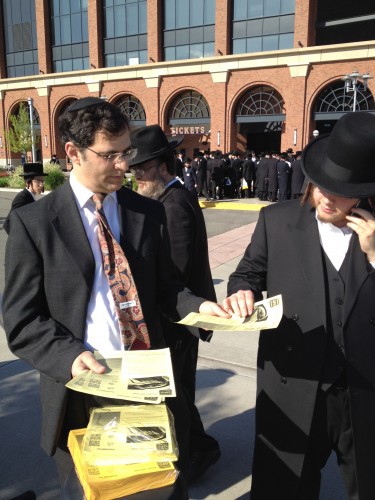

The police presence at the event was heavy but mostly confined to the background. Bomb-sniffing dogs were kept on short leashes around the perimeter of the parking lots. Getting closer to the stadium, you could feel the mood lighten to an almost jovial atmosphere. Some of the men were taking pictures together, posed underneath the glowing neon of the Citi Field signs. Near the left field gate, a man wearing a dark grey suit and a floral print tie handed out yellow flyers for his new product: An iPhone app designed to locate kosher delis and restaurants.

“I mean, it’s not practical. You can’t ignore the internet,” he said, as men in suits darker than his grabbed his flyers. To the passing event goers he said, “Free app here, not the internet. Find kosher minyanim and mikvahs.”

“I’m here to get the word out about this,” he told me. “I mean, look around, we’ve got, you know, 40,000 potential users here. Right now, we’re looking at 25,000 active app users. And I’m working on trying to find some advertisers. I need big advertisers who will pay a flat rate instead of this five cents an impression deal.”

A man in a black fur hat asked him what, exactly, was an app, and he explained it to him. The man grimaced and walked away.

By 7 p.m., the stadium was awash in an ocean of black suits with specs of white poly-cotton. It was an awesome sight, and bizarre, too, to see the empty baseball field surrounded by a capacity crowd of religion traditionalists. For whatever reason, the organizers decided to arrange the event speakers and esteemed guests on a purple dais behind the center field wall, instead of on the infield. High-ranking ultra-Orthodox clergymen took to the podium while above them a video feed zoomed in on their bearded faces. The speakers, ranging in age from forty to perhaps seventy and older, were a rhetorically gifted group. A few were even eloquent. A couple spoke only in Yiddish, but the rest delivered their speeches in strong English, peppered with Yiddish phrases. Inconsistent subtitles appeared sometimes in real time, and sometimes obviously delayed and incoherent, on the huge screen behind them. The phrasing varied from speech to speech, but the message, roughly speaking, was the same throughout: Modern technology poses pitfalls for a servant of God. There are serious questions about who needs the internet and who does not, since the internet does not belong in a Jewish home, even with a filter.

Social media, speakers argued, is a technological evil that is destroying the community’s sensibilities, sensitivities “and the way we think and live.” Many of the speakers made this point as well: Our way of life might appear to be intact on the outside, but on the inside, there are problems.

For hours the speeches went on, sometimes too loudly as they boomed over the PA system and echoed around the empty, manicured infield. In a general way, the ironies and contradictions of the event seemed almost too obvious to point out: the organizer’s use of modern technology to transmit each speaker’s critiques of modern technology to audiences around the world. The fact that in nearly every row of seats, there were men checking the screens of their Blackberries or iPhones. Less obvious but still lingering in the air was the uncertainty that the internet was really the corrosive evil the organizers made it out to be. Didn’t many men in the stadium make their living online? Wasn’t the event bankrolled, in part, by the owner of B&H; Photo, an electronic store with a strong online presence? Towards the end of the rally, many of the men in the crowd had the glazed gaze of the bored and obedient. Others were walking towards the door.

Near the end of the rally, a man in a dark black suit and tall hat asked me to take a photograph of him looking through a glass entrance door. “One with me holding the binoculars and one without,” he said, while he posed carefully against the glass. I snapped both photos while he looked on intently at a TV screen broadcasting the rally.

“Why do you want the photos of yourself?” I asked.

“I need proof that I was here, or else I’ll get in trouble. I got two pieces. This parking ticket stub,” which he pulled out of his pocket, as if to prove to me he was actually standing right there. “And now the photograph of me outside the building. It’s so people will believe that I came, so they know I was really here. Sometimes you gotta go the extra step to prove to people where you are.”

Sean Patrick Cooper’s writing has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, The Millions, The Rumpus, and other places too. He’s currently studying literary reportage at NYU, and at work on many pieces that are almost done.

Eggs Gorgoroth

I invented something delicious in my kitchen yesterday, which is not something that happens very often. I like eating food, and reading and watching TV shows about food, but I am not a great chef. This invention, however, was so delicious that it made me feel like Marcus Samuelsson. It’s an eggs dish, a scramble, and totally simple. I’ll share the recipe with you so you can feel like Marcus Samuelsson, too. (It’s hardly worth the word “recipe,” in fact.) Do you like picked herring?

This invention arose, as Frank Zappa will tell you so many do, out of necessity. There was a problem, one that had started a few days earlier when I bought three house mustard herring filets at Shelsky’s smoked fish shop on Smith Street in Brooklyn. I’ve been really enjoying Shelsky’s since moving to Brooklyn from the Lower East Side, and so sadly far away from Russ & Daughters, last year. The whitefish they get from Door County, Wisconsin, is amazingly clean and creamy tasting, and the salad they make out of it, with new pickles already mixed in, is great. As have been all the smoked fish and pickled herrings I’ve tried — up till the house-mustard variety. It’s made with whole, bright yellow mustard seeds, and a lot of them, and looked very tempting sitting in its silver tray behind the glass of the display case. When I got it home, though, and put a slice on a cracker, I found it overwhelmingly sharp. I like to think of myself as an adventurous eater, and one who appreciates big flavors, so this came as something of a blow to my ego. (Well, to the ridiculous extent that one’s palette becomes a point of pride — but it does, right?)

I put the tupperware tub in the fridge and didn’t get it out again for a few days. (While finishing all the other tupperware tubs I’d brought home along with it.) I didn’t know what to cut it with. What goes with pickled herring, really, other than crackers and other strong tastes like onions or horseradish? I don’t much like to put pickled herring on cream cheese — something about the sweetness rubs me wrong. I thought I might end up throwing it away — a shame, as I hate wasting food, and the fillets are $3.75 a piece.

Then, yesterday morning, I was wondering what to have for breakfast — single-handedly killing polar bears by staring into an open refrigerator — when I saw a carton of eggs, some leftover steamed asparagus from the previous night’s dinner, and the lonely, aging, mustard-pickled herring sitting in its clear-plastic tupperware like the Boy in the Bubble.

Eureka! It would be saved!

I scrambled three eggs (which means beating them in a bowl with a little milk, pouring them into a pot — better than a pan — over melted butter and doing as Kenny Shopsin said to in his lovely cook book, Eat Me, “Cook them slowly over a low fire and try to control yourself in terms of playing with them.”) I did not add salt, like I sometimes do if I’m having scrambled eggs on their own, but instead, while they were cooking, chopped four or five stalks of asparagus and one of the herring filets into small pieces. (Dice-sized pieces, roughly, so I guess I diced them.) When the eggs had just about reached the point of my preferred doneness (I prefer them “just right”), I clicked off the burner, added the asparagus and the pickled herring, mixed them in and scooped it all into a bowl. (I don’t know what would happened if you cooked pickled fish over a flame, but it seems ill-advised.)

Man, was it good! The rich, buttery eggs softened the mustard and brine of the herring just enough. And the asparagus added some bright, healthy green to the flavor. “Scandinavian Scramble,” I thought to call it. But the taste was still so big and bold, and, really, particularly Norwegian, as opposed to Danish or Swedish. (I’m making this up now, I don’t know the distinctions so well. I’m just making up a reason for myself to find a better name.) I figured it could stand up to something intense and powerful, the forces of darkness. So I went with Gorgoroth. “Eggs Gorgoroth.”

I made them again for lunch today. Yum.

Why Does Vinyl Sound The Best? A Chat With A Musician Who Knows

by Seth Colter Walls

This post is brought to you by got milk? Find out what else is fake at scienceofimitationmilk.com.

I have a confession: I don’t think I can rightfully be counted as among the new wave of vinyl fetishists. Sure, I own a turntable, like any proper trend-piece-generating/hating Brooklyn-residing arts-interested person, but I don’t listen to as many releases as possible on it. Sometimes, twirling around a piece of audiophile-approved, 180-gram, 12-inch plastic, before commencing with the nervous hovering of the tone arm whilst wondering if the needle needs replacing, I’m as apt as anyone to think: “oh for the love of Steve Jobs, let’s just press a button marked ‘play’ and get on with life already.”

But despite all that “the cloud” has promised us, not all music of interest has made it over into a digitized format just yet. For example: one of my favorite “new wave”-era bands is this group that called themselves Tirez Tirez. They opened for Talking Heads quite a bit; like R.E.M., they called the IRS label home for a part of the 80s; they sometimes used interesting/irregular metric patterns and syncopations, and even when not, had great melodies, which were written by frontman Mikel Rouse. Yet only their last album as a working group, Against All Flags, was ever put out on CD. It’s the sort of minor tragedy that sends one to eBay and Amazon Marketplace, ready to pay too much for the original vinyl pressings.

Rouse, who after the band’s demise became a producer of various pop and classical things, has a handle not just metrical complexity and the like — but also about why it is that vinyl hits our ears in a particular way that CDs can’t.

It’s something he’s been thinking about a lot lately, given that, in 2010, the New York Public Library acquired his archive. Since then, Rouse has been at work digitizing his back catalog of analog material. After Tirez Tirez, Rouse went on to have rather a successful career as a writer of multimedia modern operas (or “stage pieces,” if you get all in a swivet about the word “opera”) that have played at Lincoln Center and BAM, such as Dennis Cleveland, and Gravity Radio. (I interviewed him recently about his excellent new song-based double album, False Doors/Boost.)

Seth Colter Walls: Mikel, what are all the reasons for vinyl being a bigger deal now than it was, say, in the last two decades?

Mikel Rouse: Of course the obvious thing to many people is that analog sounds better than numbers approximating analog. And I don’t think one can dismiss the tactile nature of a record and the aspect that you can actually perceive time passing. Also, due to the time constraints of fitting sound onto a vinyl disc — a 15- to 20-minute limit per side — you actually get a pretty good time frame for human attention, as opposed to the extended time of CDs, around 70 minutes, and the perceived need to fill that space, whether one has enough good material to fill the space.

Personally, I think one of the main reasons folks think vinyl sounds better is the limited frequency range a disc requires to fit the sound on the disc. Digital doesn’t have this limitation, and while that theoretically should be a good thing, our ears have had 70 years of conditioning to the limited frequency range of vinyl discs.

Let’s listen to an example by streaming some music-on-vinyl that you own the rights to. This is your 1983 single “Under the Door,” which is one of my favorites from your catalog. I think I also like my particular vinyl “rip” of the song. Is there a good reason for that? Anyway, I like being able to listen to this song and all its zig-zagging synth ostinatos while out and about, which is why I have it on my phone.

I think your vinyl transfer might sound better to you for the reason I [just] mentioned — because the frequency range on the vinyl is rolled off a bit in the highs and lows. This can make the music seem more “rounded” toward the middle frequencies. This single was also recorded to 2-inch tape, and tape compression has a big effect on the sound quality of analog recordings.

You’re now in the process of remastering and digitizing your boxes and boxes of old analog tapes and vinyl recordings for your “living archive” at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Has that process taught you anything about old analog formats like vinyl versus the digital “future” everyone’s always talking about?

Archiving the analog masters was a real eye opener. Of course, I mainly wanted to preserve some historic recordings before the analog tape degenerated too much. Most of the tapes had to be “baked” in order to be played and transferred to digital. But I was also hoping to unearth some distant gems I might have forgotten. (That didn’t happen as much as I would have hoped!)

But something else did happen. Even if there was a so-so tune or questionable mix, there was still this truly familiar sound quality to all of the recordings. And that sound was the sound of tape compression. I’ve had the good opportunity to work with a number of great recording engineers over the years, like Martin Bisi and James Mason. These engineers knew how to “hit the tape” in such a way that the tape acts as its own kind of compressor. So after hearing this, I set about to upgrade my studio with more analog/tube eq’s and compressors. I’ve also used two-track tape with a sync tone to get a tape sound that I then transfer to a digital workstation.

When we were talking about one of your two new records, Boost, you were mentioning how you ran all the electronic percussion material through some vintage tube amps, I think? Your recent records really have had an amazing “sound” to them, quite apart from the intricacy of the various parts. Can you describe a bit your learning curve on this end, in making the complex density of things on a song like “Professional Smile” (David Foster Wallace fans take note) sound like pop music? Or on a song like “Orson Elvis”?

It’s a great question because over the years I’ve really tried to mix my love for complex metric structures with my love for classic pop production techniques. The problem is, much great pop music is fairly stable metrically and much of the instrumentation is vamping or enhancing a similar structure — this is obviously an over-generalization, but you get my point.

Rouse’s two new albums are available to stream from their BandCamp page. Toggle through the embedded player to find the songs under discussion below.

So you can love that luxuriating sound that pop music can build up with layers reinforcing each other. But my work uses layers of great complexity that are crossing and contradicting each other. So common pop techniques like compression have to be used very carefully or everything just turns to mush. The idea isn’t to use complexity for complexities sake. It’s because in a track like “Professional Smile,” I’m digging the tearing-your-head-off effect that these multiple meters produce. And when those kind of unexpected metric combinations collide with very current, formulaic techno sounds, it becomes both familiar and unknown at the same time. I like hearing “Professional Smile” in a club or a bar because everyone is talking over it, and it just sounds like a lot of the typical stuff you could hear due to the production value. But then when people notice what’s actually taking place in the music, it kind of throws them a curve. And a lot of people seem to get that. It’s not a trick; it’s offering a tune on a combined number of levels. Tap into any level you like.

“Orson Elvis,” for example, has a multi-tempo rhythm going on that could be a similar effect to the two tempos one can experience in dubstep music. But because these multi-tempo rhythms in “Elvis” are also cycling around each other, rather that staying within the same 4-bar structure, the effect is quite remarkable. Also, adding the steel guitar and vocals circling around all of this controlled chaos sets the mood for the lyric content. So the metric guitar/vocals/sequencer combinations are there to set the text and kind of illustrate or orchestrate the text meaning:

Every hit on line

Takes its toll in time

Time you don’t get back

Running with the pack

Miracles agree:

What we really need

Takes us off the grid

Back to where we live.

Part of the song is about the life lost from social media. And the juxtaposition of the tempos heightens this feeling of instability.

Can you tell us what is even going on with the rhythms in this song, exactly? (We enjoy weirdly specific knowledge of things.)

After a vocal entrance of two cycles of 3 and 7, “Orson Elvis” starts with this sort of loping 7 meter phrase on percussion doubled by steel guitar. This is an accompaniment to a short vocal narration. But beginning with the sung phrase: “If Hollywood instinct is right on the money,” a faster electronic percussion pattern in 5 comes in propelling the vocal entrance.

But this isn’t simply a metric juxtaposition of 5-against-7, because the two patterns are in different tempos. So where a simple 5-against-7 phrase would mean the “5 phrase” repeats seven times and the “7 phrase” repeats five times to complete one full cycle. In this case you have the moment of periodicity after the “7 phrase” has repeated eight times. It’s basically a tempo canon, but in conjunction with the techno beats, it’s an arresting effect.

I’m pretty into it. Anyway: thanks for talking about this and vinyl and everything else!

Rouse: Sure!

Related: When Did The Remix Become A Requirement?

Seth Colter Walls is a culture critic and reporter for Slate, NewYorker.com, The Village Voice, Washington Post, Capital New York, and lots of other places. His favorite Mikel Rouse album is Recess. Top photo by Andrea Ciambra; photo of Rouse by Betty Freeman.

Sponsored posts are purely editorial content that we are pleased to have presented by a participating sponsor, advertisers do not produce the content.

Women Unamusing

“Female bosses are less likely to make jokes in the boardroom because they are met with an awkward silence for eight out of every ten attempts at humour, a study has revealed.”

Celebrate The Notorious B.I.G.

This video is what the best MC ever to pick up a mic looked and sounded like when he was 17. Seventeen! Brooklyn’s Biggie Smalls was born forty years ago today. Ego Trip has ten rarer videos up to mark the occasion. But this one always blows my mind when I watch it. The way he carried himself, his posture, his enunciation, the control he had of that booming voice — he knew how great he was already.

"Prehistoric Facebook" Also Sucked

“Cambridge boffins are studying a ‘prehistoric version of Facebook’ to gain a unique insight into the daily lives of our ancestors. Scientists are analysing thousands of images scrawled across two granite rock sites — each the size of a football pitch — in Sweden and Russia. Archaeologists believe the sites were an early form of ‘social networking’ used by Bronze Age tribes to communicate with each other.”

The P.T. Anderson Cult Movie Trailer Is Here, Oh My God

*SCREAMING*

(Cult movie like, movie about a cult; not cult movie like “cult movie.”)

Things I Didn't Get To Eat (Or Drink) At The Great GoogaMooga

Things I Didn’t Get To Eat (Or Drink) At The Great GoogaMooga

by Heather Wagner

I ventured from lower Manhattan to Prospect Park this past Saturday with all intentions of enjoying myself at The Great GoogaMooga, an unfortunately titled food and music festival featuring some of New York’s biggest, baddest-ass culinary luminaries: Blue Ribbon, Spotted Pig, Char No. 4, Co., Colicchio & Sons, Luke’s Lobster, The Meat Hook, Roberta’s — over seventy A-list vendors ready to serve a discriminating crowd. This was the festival’s inaugural year, its first crack at becoming a welcome-to-summer institution, a chance to satiate palates both rugged and refined, and a venue for all to experience Brooklyn at its most food-obsessed. But like a maple-cotton-candy-on-a-pretzel ($5), it turned out to be initially enticing — but ultimately unsatisfying.

My adventure started auspiciously enough. The Googa Gods had shined down upon Prospect Park; the sun was out on a clear, bucolic 74-degree day. I had, however, arrived on the wrong side of the park and was forced to ask a laconic cop for directions.

I could not wrest the words “Where is The Great GoogaMooga?” from my mouth. So instead, I asked him, in a low mumble, where “The Festival” was.

“Yeah, yeah, that Gunga Munga thing? Take a right on 16th, you’ll see it.”

I entered the park and came upon a large fenced-in expanse of Nethermead Meadow. Smoke billowed from dozens of cheery, Old West-style vendor stations emblazoned with names like Bacon Land and Foie Gras Doughnuts. Police barriers contained a shuffling line of prospective attendees as a ’90s cover band blasted hits that nobody necessarily need hear again (is anyone dying for a 311 revival?). I arrived at the entrance and presented my ticket. Entry was free but you still needed a ticket with a QR code. You could also pay $249.50 for “ExtraMooga,” which entitled you to a separate entrance, special VIP dining areas, prime concert seating, and access to a lounge where it was promised you could brush elbows with the likes of Chuck Klosterman and Patton Oswalt.

I passed on that and headed into the plebian entrance. I was then presented with a staggering line for ID Check, necessary for the procurement of adult beverages.

So, a sober day in the park it would be then! There was also the option to invest in “Googa Moula,” a pre-pay system that streamlined the beer-and-wine process, but it seemed like such a haphazard operation that I chose to soldier on.

On the main stage, Pedro Martinez was playing muted Cuban beats. Scores of hungry attendees waited patiently in lines that stretched up to 50-deep. April Bloomfield’s Spotted Pig Burger was the most in-demand, ‘natch.

At this point I realized that chronicling more than a few personal culinary experiences might take hours to accomplish, so I decided to simply take pictures of other people’s hard-won food instead:

A gregarious girl’s Roberta’s Pizza.

A mellow dude’s Blue Ribbon Fried Chicken.

A stressed mom’s Luke’s Lobster.

An affable girl’s Pickle-on-a-Stick from Eat Me Sweetly.

A proud server of Crawfish Monica.

Hefeweizen in an unidentified sport sandal.

Despite the well-chronicled vitriol in re: Artisanal Brooklyn and its evil, pushy, narcissistic breeder population, the crowd seemed overwhelming good-natured, kind and, dare I say, eerily docile? Perhaps because they, too, were sober and weak from hunger.

Yet there are always some fascinating, mildly irksome standouts. Why is there is always a guy with a hula-hoop at outdoor festivals? What’s the connection? I guess it’s just fun and “anti-mainstream” kooky, like joss sticks or a hacky sack. Behold the pure childlike wonder on this 37-year-old man’s face:

And hey, it’s the cast of “Girls”! Ha, just kidding. I actually don’t get HBO but figure they must look somewhat like this.

Hold up… naked guy? Finally, someone’s shaking things up! Upon further inspection, he was actually wearing flesh-tone shorts artfully obscured by the police-barrier/dining stand.

Goth-Queen parasols also seemed to be a trend.

As were Excessively Photogenic Guys.

And some Good-ol’-Bros for good measure.

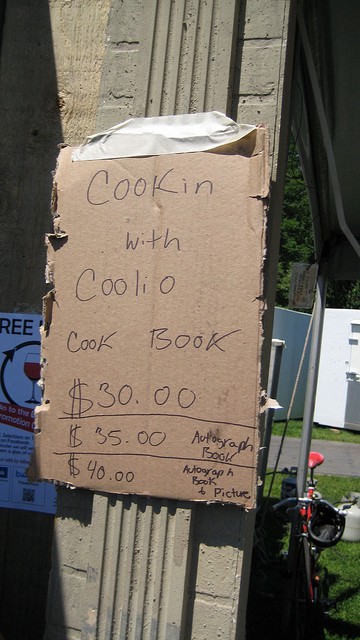

Chef Coolio was in the house!

This guy was stationed here the entire time.

By far, the highlight of the day was witnessing a slaphappy crew delightfully digging in to a pig face. Yes, a literal pig face. They had apparently won this Saw III-reminiscent prize in an arm-wrestling competition at The Meat Hook’s station. Please note this brave gentleman extracted an eyeball from the pig’s face to imbibe.

It looked rough going down but he was a good sport.

I left at 4 p.m., before the scheduled sets of Holy Ghost! and The Roots. I heard via Twitter that GoogaMooga had run out of beer and wine at this point but were trying to resolve this situation. I posit that the first year of any festival of this undertaking must naturally be a bit of a hit-or-miss experience and that the organizers certainly meant well. And perhaps things got better when the sun went down. But alas, I could not stay. I had a reservation at Corton that night. It was delicious.

By the way, I was tempted to buy a $15 GoogaMooga plastic Spork to commemorate the occasion. But not tempted enough.

Heather Wagner is a copy director at Elle and author of Friend or Faux and Happiness on $10 a Day. Follow her on twitter at @heatherwag or read her inevitable tumblr.