Rackurracy Is Important

“In a June 24 story about the growth of Hooters-style restaurants, The Associated Press misspelled the names of the CEO of Tilted Kilt Pub & Eatery and the owner of Mugs N Jugs. The correct spellings are Ron Lynch and Sam Ahmed, respectively.” And there’s a photo!

What a Town! Tonight's Dueling Readings and Book Parties!

Supplemental reading: Marco Roth and Gideon Lewis-Kraus at 192 Books; the n+1 reading at KGB; Barefoot Runners NYC. (Subscribe on iTunes)

Are You Smarter Than a Legal Rockstar? Obamacare at the Supreme Court

by Eric Spiegelman

“Perhaps,” Ezra Klein wrote last week, “the Supreme Court will surprise us on this one” — meaning the Court might not overturn the part of the Affordable Care Act that would require nearly all Americans to maintain at least some amount of healthcare insurance. “But if they don’t, I think the right question will be why so few in the legal academy saw it coming.”

The list of constitutional law scholars who have stated publicly that the individual mandate is constitutional includes some of the most famous legal minds in the nation. Laurence Tribe. Kathleen Sullivan. Ronald Dworkin. Lawrence Lessig. Mark Tushnet. Eugene Volokh. These are con law’s rockstars, who regularly dominate the lists of most-cited authorities. All believed the individual mandate to be a perfectly acceptable use of Congress’s power to regulate the economy or levy taxes. The possibility that they might be wrong sent a couple of them into a tizzy. “I’ve only mispredicted one big Supreme Court case in the last 20 years,” said Akhil Amar, another rockstar, told Klein. “That was Bush v. Gore… If they decide this by 5–4, then yes, it’s disheartening to me, because my life was a fraud. Here I was, in my silly little office, thinking law mattered, and it really didn’t. What mattered was politics, money, party, and party loyalty.”

It’s not really as dramatic as all that. The case — officially Florida v. United States Department of Health and Human Services — will likely be quite closely decided for two reasons that have nothing to do with politics or money or party loyalty. The first reason is a philosophical one: this case pits two very old and fundamental constitutional values against each other in a way that we haven’t quite seen before. The second reason stems from the current composition of the Court, which has four conservative to conservative activist judges, four liberal to fairly liberal judges, and Justice Anthony Kennedy. It has never been clear where something like Obamacare fits with Kennedy’s view of the Constitution. And that loops back around to the first reason, so let’s start there.

At the end of the Revolution, each American colony became, essentially, its own sovereign nation. Like any group of sovereign nations, they had some troubles getting along, especially when it came to trade. Some states tried to impose tariffs on products made in other states, and those states responded with their own protectionist policies. It was kind of a mess. Believing that free trade would ultimately be a better approach, the states entered into a union. They tried this twice; the first time didn’t take.

The Constitution, which came out of the second attempt, is largely a multiparty economic treaty. The America of 1789 has much in common with the Eurozone of 2012. In both, sovereign nations gave up their right to individual currencies in favor of a “multinational” one, and they agreed to drop all interstate tariffs and other forms of protectionism. Unlike the Eurozone, however, the American Constitution created a central regulatory agency: the federal Congress. In order to make sure Congress could do its job, the states had to grant it certain powers.

The powers of Congress, listed in Article I of the Constitution, are referred to as “enumerated powers,” meaning that Congress can only do the things specifically listed. (The list includes the so-called “commerce clause,” which gives Congress the power to regulate commerce “among” the states.) This limitation was by design. The states were concerned that the new government might try to assert itself outside of the agreed-upon boundaries. It was a sentiment reflected by the Tenth Amendment, added not long after the Constitution was ratified, which says that any powers not delegated to Congress were “reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” Among the powers the states had in mind were these things called the “police powers.”

The police powers include basically everything that a state government can force an individual to do. Forcing someone to pay income taxes is one such power (and a power not granted to the federal government until 1913). Regulating for the public health (like quarantines), safety (helmet laws, zoning) and morals (blue laws, curfews, banning foie gras and/or Big Gulps) is another. The states didn’t want the federal government pushing their locals around. Pushing locals around is the state’s job.

These two values are put into direct conflict by the individual mandate provisions of the Affordable Care Act. On one hand, healthcare costs would decrease if everyone in the United States had health insurance, so coercing people to buy health insurance is a way to regulate the economy, and Congress has the power to regulate the economy. On the other hand, this form of coercion is a police power, and it’s not a police power specifically enumerated in the list of those granted to Congress.

Conservatives lined up behind the latter value. If Congress can coerce an individual to do something, and exercise a power apparently owned by the states, and they can do so in the name of regulating commerce, then what can’t it do? How far can the definition of Congress’ enumerated powers be stretched? As Justice Scalia asked during oral arguments: if Congress can force you to buy health insurance, can they also force you to buy broccoli? The question I like to ask is: what if Congress forced you to buy a gun?

Where Kennedy stands on all this is something of a mystery. Even his own former law clerks can’t seem to agree. About as close as you can get to insight into the way Kennedy might rule is his concurring opinion in US v. Lopez, in 1995. In that case, the Supreme Court struck down a federal law as being outside the scope of Congress’s powers under the commerce clause. He wrote: “were the Federal Government to take over the regulation of entire areas of traditional state concern, areas having nothing to do with the regulation of commercial activities, the boundaries between the spheres of federal and state authority would blur and political responsibility would become illusory.” You can read that to be in favor of the individual mandate — or against it.

People really seemed to think Kennedy would be pro-mandate, at least until oral arguments, when he levied a series of tough and highly skeptical questions at the Solicitor General arguing the case. But even then, closer inspection revealed some doubt. Nobody knows for sure which direction Justice Kennedy, who is presumably the fulcrum on which this case balances, will tip the scale.

Back to Ezra Klein’s question. For a case that is close on both objective and subjective grounds, why are the top legal scholars in the country so certain the law at issue is constitutional? At heart, it’s probably wishful thinking. They argued what they believed the law should be. That, ultimately, is a responsibility of everyone in the legal profession; advocacy lies at the heart of the job. When faced with that kind of uncertainty, the best you can do is say what you think the law should be. Justice Kennedy actually does the same thing when he rules on a case. The difference is, when Justice Kennedy comes to believe what the law on mandatory insurance should be, that is what the law is.

Eric Spiegelman went to law school.

Don't Worry About Being Late: You're Never Off The Clock Anyway

“Bosses in the U.S. and parts of Europe are less strict about employees showing up at the office on time, trusting that they are working long before they actually get to the office thanks to the growth of smartphones, the cloud and other ways to access work remotely, a new study suggests.” [Via]

16 Things You Can Do With Your Free Hand, Besides Catch A Baseball, While You're Holding A Taco...

16 Things You Can Do With Your Free Hand, Besides Catch A Baseball, While You’re Holding A Taco Bell Beefy Nacho Burrito In Your Other Hand

1) Deep fry Snickers bar

2) Drink 64 oz. tub of soda (somewhere other than New York City and Cambridge)

3) Eat KFC Double Down Chicken Sandwich

4) Sprinkle extra shredded cheese on Taco Bell Beefy Nacho Burrito

5) Spray Cheez Whiz directly into mouth

6) Stuff entire hard-boiled egg in mouth, squeeze packet of mayonaise directly into mouth atop hard-boiled egg

7) Crumble potato chips onto cheeseburger

8) Spread butter on steak

9) Dip corn dog into marshmallow fluff

10) Shovel handfulls of M&Ms; into mouth

11) Fish sausage links out of pocket

12) Order Domino’s

13) Eat two slices of pizza stacked one-on-top-of-the-other and tied together with Slim Jim

14) Drink mug of Cool Ranch salad dressing

15) Pour mug of Cool Ranch salad dressing on chest

16) Eat other Taco Bell Beefy Nacho Burrito

Hurricane Names That Spell Trouble: An Unscientific Survey

Hurricane Names That Spell Trouble: An Unscientific Survey

On April 13th of this year, the name Irene was officially retired from the list of Atlantic Basin Hurricane names. In all, six Hurricane Irenes have raged around the Atlantic, but there won’t be a seventh. The screenshot here, taken from NOAA’s Historical Hurricane Tracks (a complete timehole of an application) shows all of the past Atlantic Irenes.* Irene 1971 actually hopped across Nicaragua to become a Pacific storm, Hurricane Olivia, something that’s happened only a handful of times in recorded meteorological history: Irene-Olivia was the first named storm to do so. Irene 1981 struck France. Then Irene 2011 rolled up the East Coast last summer. Clearly, it was only a matter of time before the name was sent to live on a farm.

Irene will be replaced by Irma, who sounds just lovely. But nice, unassuming names can wreak havoc, too. The five strongest hurricanes since we started keeping track are: Camille, Allen, Gilbert, Wilma and Mitch. Hurricane Fifi was responsible for 10,000 deaths. Hurricane Lenny caused $1.24 billion (in today’s dollars) damage. The perceived toughness of a name really reflects nothing about the hurricane itself. So what? Let’s throw our qualms about correlation/causation out the window and see if there are any patterns we can squeeze out of this list of retired storm names!

The World Meteorological Organization in Switzerland decides storm names. Originally, names were nonstandard. Oh, this storm destroyed a boat? Name the storm after the boat! And so on, all very haphazard. For a few years, the phonetic alphabet was used. Then. in 1953, a list of alphabetically organized non-repeating women’s names

were defined to formally christen storms, giving us decades of grandma-sounding hurricanes, like Flossy, Gerda and Ethel. In 1979 the list was amended to alternate with male names and repeat itself every six years. Particularly devastating storms, it was agreed, would have their names “retired,” to prevent future confusion. Retired names are replaced with ones of the same gender and usually origin (Atlantic names come from English, French, and Spanish. So Juan was replaced by Joaquin, Gaston replaced by Georges, etc.). Seventy-six names have been retired so far. There’s been some discussion about whether Gracie, which made landfall in Georgia and South Carolina as a Category 3 storm, is really retired or not, but it’s been off the lists since 1959, and since it’s unlikely to end up used again unless the head of the WMO has a real yen to rile up a bunch of weather nerds, I’ve included it in the count here.

As the six-cycle system was implemented in 1979, we’ll start there. If a greater number of retired names equates to more active seasons, let’s see which name cycles have been more devastating than the others. Are any of them overachievers or total slackers?

Individual cycles (including future years of some because the columns line up so nicely):

A (1979, 1985, 1991, 1997, 2003, 2009): 8 retired names

B (1980, 1986, 1992, 1998, 2004, 2010): 10 retired names

C (1981, 1987, 1993, 1999, 2005, 2011): 8 retired names

D (1982, 1988, 1994, 2000, 2006, 2012): 3 retired names (so far)

E (1983, 1989, 1995, 2001, 2007, 2013): 12 retired names (so far)

F (1984, 1990, 1996, 2002, 2008, 2014): 10 retired names (so far)

As you might expect, things are more or less even (important to note that in Cycle C, five of the seven names were retired in 2005 alone). Does an uneventful history for Cycle D thus far mean we can expect a calm year in 2012? Maybe! The last retiree went down in 2000, so we’re overdue? Maybe! That’s the nice thing about statistics based on meaningless distinctions: draw your own conclusions. Shoot for the moon! If you miss, you’ll burn up in the atmosphere on your agonizing descent.

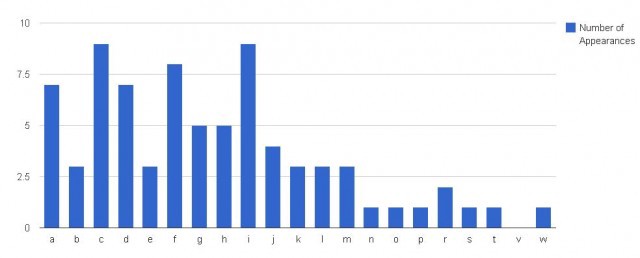

The name frequencies themselves are a bit more useful, as they’re not on an arbitrary six-year cycle (so we will use the full 1950-onward list), but serve as more of a seasonal indicator. Here’s a chart showing frequency of retired names by letters of the alphabet.

The most retired names are C and I names, with nine each, closely followed by eight Fs and seven As. Of eligible letters, only V remains unretired. This makes sense; most hurricane seasons don’t make it that deep into the WMO’s 21-letter alphabet (no Q, U, X, Y, or Z). V and W named storms didn’t appear at all until 2005 (in the ocean, not on the list. They’ve been on the list, just unused). Personally, I’m hoping for that to change in 2014. Do me proud, Hurricane Vicky!

* There have been a handful of South Pacific Irenes, and the name’s still active for that region.

Previously: How To Not Get Lost

Victoria Johnson devotes the same ardor to hurricane season and hockey season. She is thankful there is only minimal overlap.

Chef Gets His Knives Out

“He has entirely bought into the establishment idea that table clothes, square plates, and stars define an objectively good restaurant. The value system he applies to Harlem is not one the community has ever accepted, and frankly, the rest of New York’s neighborhoods and food scenes are rejecting it as well. While the rest of us are busy winning over New York City with fistfuls of cilantro, funny glasses, and raw dining rooms, Marcus is up in Harlem plowing for the old guard — trying to carve out a new market for an outdated sensibility. He’s importing a concept on its last legs and trying to convince Harlem it’s new and worthy. Red Rooster might work better in a place like Las Vegas’ New York New York Hotel, a sorry attempt at recreating the city for people walking around with souvenir drinks. It doesn’t belong in Harlem.”

— Oh my. Baohaus chef and columnist Eddie Huang does not like Red Rooster chef and memoirist Marcus Samuelsson.

Hope You Can Swim, Coastal Elitists

“A new U.S. Geological Survey report published Sunday says that sea levels are rising three-to-four times faster along parts of the U.S. east coast than they are globally.”

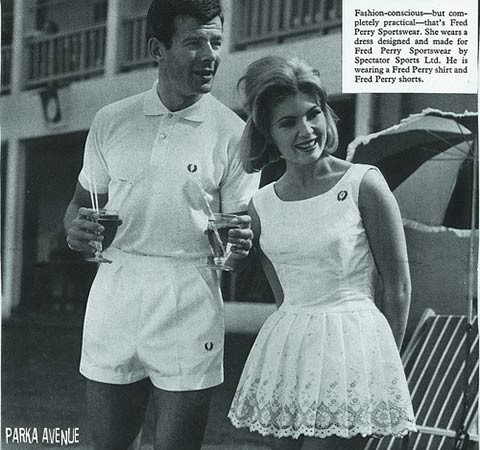

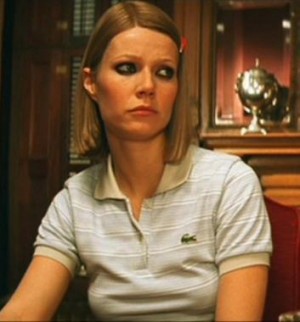

A Tale Of Two Tennis Shirts

by Jason Diamond

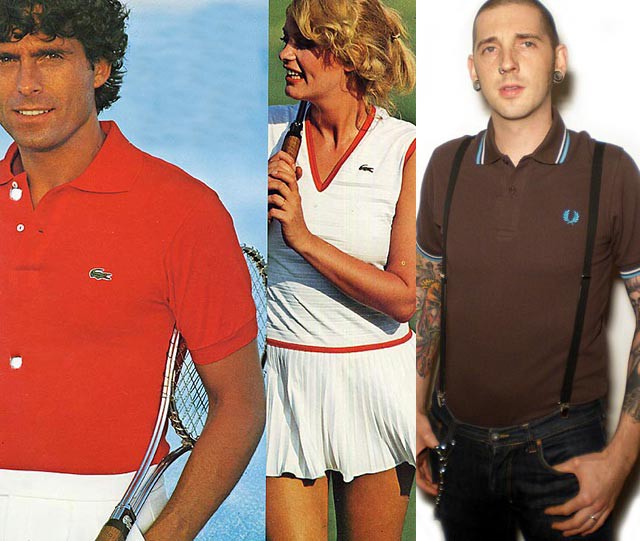

According to Google Maps, you have to walk 232.9 feet (17 seconds) to get from the Lacoste Boutique on Prince Street to the Fred Perry store on Wooster Street in Manhattan’s Soho neighborhood. Yet despite the fact that they’re practically neighbors, the stores feel like two different worlds. At Fred Perry, your salesperson is a short girl with a Scottish accent, a labret piercing, and a Chelsea Girl haircut. “Shot by Both Sides,” the biggest hit by Howard Devoto’s post-Buzzcocks band, Magazine, is blasting over the speakers, and the wares are arranged neatly, leaving sizeable gaps between each item in a way that leaves valuable floor space wide open. The shop looks modern, if by modern you mean ‘mod,’ which, as it happens, was one of the youth subcultures that incorporated the clothing brand into its uniform back in the 60s.

Across the street at the Lacoste store it’s an entirely different story: It’s bright, this season there is a ton of neon, and Rihanna is blasting out of the speakers. Shoppers are greeted by a gaggle of employees who, between them, fulfill just about every hipster cliché you can throw out — big glasses, asymmetrical haircuts, ripped up layers fashioned after Rodarte runway looks. The Lacoste shop is also very modern; modern as in, very much of the time and place it occupies.

But what the two companies lack in comparable aesthetics, they make up for in their very similar histories: Wimbledon champions founded both brands — René Lacoste started his company in the late 1920s, while Perry’s shirts made their first appearance in 1952 — and both companies became famous for manufacturing very similar looking tennis shirts. These shirts are casually referred to today as “polo shirts” (which is technically wrong: the term polo shirt originally referred only to the long-sleeved button-up shirts worn by polo players). Even though the shirts look and feel similar and cost about the same (Lacoste shading a little less expensive), somewhere down the line the laurel wreath of Perry’s logo became a favorite of mods, skinheads, rude boys, football hooligans and Brit Poppers, while Lacoste became the sport shirt of choice for the rich and privileged and anyone looking to be seen as such. But why did it turn out that way?

***

I meet Paul for beers at a bar off St. Mark’s Place. Paul is about 6-foot-4 and built like a brick house. He’s got a muscular build that looks natural, not like it took years to chisel at the gym, “It’s working-class physique,” he says with a smile as he lifts up his right sleeve to show off the laurel wreath tattoo he got as a tribute to his favorite clothing brand.

With his buzz cut and imposing build, Paul looks like the stereotype of a Fred Perry loyalist, and indeed he’s worn the company’s shirts “at least three a week since the 1980s.” He grew up in England; he was fourteen when Margaret Thatcher became prime minister in 1979. He tells his story in a whimsical, almost Dickensian way: “I was a pissed-off kid. I’m not quite sure at what it was I was so angry with, but Thatcher didn’t help things much. So I decided I should let people know I was angry.” With the aid of his mother’s leg razor, Paul became a skinhead because “it looked fucking tough,” and, soon after that, acquired his first Fred Perry shirt through questionable means, “I took it off some guy’s back after a fight. I said to him, ‘that looks like my size,’ and I just pulled it off.”

As he reminisced about his reckless teenage years, Paul was careful to point out that, no matter how out of control the rest of his life got, he always took great care of his Fred Perry shirts because you “could only afford one or two of them.” Some of his friends, all skinheads, made fun of him, saying he looked like a “fucking mod” wearing Fred Perry shirts. “The real salt of the earth guys,” he said of them.

Paul outgrew the skinhead lifestyle around the time he says that it started becoming synonymous with the racist National Front. He’s the child of a white English father and a black, Jamaican-born mother, and his mother was alarmed by the images of angry men with shaved heads wearing Fred Perry shirts marching through the streets, chanting to deport non-English born citizens. “She didn’t understand I wasn’t one of those kind of skins; it was hard for her.” He continued: “I eventually got into E” — ecstasy — “and realized I didn’t need the violence. But I always wore Fred Perry. Still do.”

When I pressed him to explain why he thinks Fred Perry shirts became so popular among pissed-off British youth, his response was carefully chosen. “I’ve always been a Man. United supporter. All my friends were Arsenal, but my dad was from right around Manchester.” He paused. “They weren’t the team they are now, but I suppose if Bestie [late soccer legend George Best] had made shirts, I’d be wearing them today instead.” When asked whether he’d ever consider buying another brand of tennis shirt, he doesn’t hesitate for a second: “No.”

There are a lot of brand loyalists like Paul, and the continued popularity of Fred Perry shirts among the likes of contemporary skinheads to “The Modfather” Paul Weller, and the Pitchfork-approved Danish hardcore band Iceage as an idiosyncratic factoid that Malcolm Gladwell could write a New Yorker article about. It’s easy to attribute the phenomenon to tradition, like loud music and drugs, and figure that the shirts are just part of the entire youth culture package. But why Fred Perry? Why not Lacoste? The two shirts are practically identical: Both 100% cotton pique tennis shirts, both retailing in America for $85 to $90. Yet somewhere along the way, Fred Perry shirts became linked to a skinhead culture that prides itself on its working-class background, while Lacoste shirts, called the “sport shirt of choice” by The Official Preppy Handbook in 1980, have been a country club staple ever since. Two shirts named after athletes who excelled in a sport that is generally played and enjoyed by people with the leisure and money for expensive lessons and court time.

But while Lacoste and Fred Perry may have built the same shirt, Lacoste was built from the top down and Fred Perry from the ground up.

***

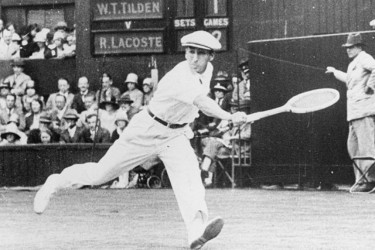

To begin, understand that René Lacoste is the father of the modern tennis shirt. Before Lacoste, tennis players were running up and down the court wearing uncomfortable flannel trousers and shirts — style won over functionality in those days. Trying to keep the players looking clean and proper, Wimbledon officials instituted a strict “tennis whites” rule in 1890, the light colors better camouflaging the players’ sweat. Lacoste, the son of a wealthy businessman, was one of the world’s best tennis players. Enrolled into one of the most prestigious schools in France, Lacoste was pegged to follow in the footsteps of his businessman father. Instead, he found himself attracted to the game of tennis. His father (an understanding man, to say the least) gave his son five years to excel in the sport. By 1925, he’d won his country’s major, The French Open, becoming one of the “Four Musketeers” of French tennis, a group that won a combined 20 Grand Slam titles for their country between 1924 and 1932.

Even during the height of his playing career, Lacoste’s creative streak never left him. He’s credited with creating the world’s first tennis-ball machine, and, long after his 1963 retirement, he took out a patent on the tubular steel tennis racquet. But it’s his short sleeve jersey petit piqué cotton tennis shirt that was his most revolutionary creation. Sleek, stylish, white, and, above all other things, comfortable, Lacoste first wore the shirt during the 1926 US Open (which he ended up winning), and the new style became a sensation.

Lacoste was the first athlete to sell merchandize emblazoned with his logo: the now ubiquitous crocodile (In fact, the Lacoste company claims, to some dispute, that Lacoste’s shirt was the first article of clothing to sport a visible brand name.) In 1933 Lacoste co-founded La Société Chemise Lacoste, and the shirts went on sale to the public.

Fred Perry, who was five years younger than Lacoste, spent much of the 1930s as one of the best players in the world. He won three Wimbledon titles and was the first player to win all four Grand Slams in his career. Seeing Lacoste’s success, Fred Perry launched his own tennis shirt line in 1952 during his native country’s biggest tennis championship, Wimbledon. The shirts became a huge success in England, outselling Lacoste shirts within five years, and the company eventually moved into other tennis gear. As Paul described it to me, “It got to be like Michael Jordan and Nike. They were comfortable and your dad wore them on the weekends even if he didn’t play [tennis].”

While Fred Perry focused on growing its business in England, Lacoste was expanding westward. The shirts first appeared in the U.S. in the early 50s, at the then-hefty price of about eight dollars apiece. Marketed as “the status symbol of the competent sportsman,” the shirts were sold in high-end department stores on Madison Ave. and by Brooks Brothers. They were a hit. After taking over the company from his father in 1963, Bernard Lacoste — along with the British clothing company Izod, who purchased a stake in Lacoste in 1953 — the company started outfitting presidents and entertainers. By the mid 60s, the company had expanded to offer shirts in a variety of different colors.

Meanwhile, Fred Perry shirts remained a very English garment. They were passed down in working-class families from fathers to sons, looking fashionable enough to be matched with army surplus parkas leftover from the war, pork pie hats, and sta-prest trousers as part of the uniform for mods of lesser means that couldn’t necessarily afford the expensive custom suits that other mods wore.

Soon, the “hard mods” were choosing more working-class accessories like work boots and suspenders, and the skinhead subculture evolved out of that fading London mod scene. By the close of the 60s, The Who were putting out rock operas; amphetamines gave way to psychedelics; and in many cases, mods became hippies. While the association between skinheads and racism is now almost instant — thanks to organizations like the National Front latching on to their tough look — they were the working-class face of British youth subculture before punk, and Fred Perry tennis shirts were an important part of the equation.

The 1980s turned out to be the decade of the tennis shirt; closets all across America held Penguins and Le Tigres. Lacoste and Ralph Lauren battled for the hearts and cash of Americans from coast to coast. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s possible to see that Lauren’s Polo brand won the battle, due to Lacoste’s oversaturation of the market and Lauren’s superior branding. In a 2006 interview with Businessweek, René Lacoste’s grandson, Philippe Lacoste, discussed the company’s fall from grace, saying its prestige “eroded over time because we expanded our distribution channels, and even were sold in J.C. Penney.”

By the time the 90s rolled around, the preppy look was out and nobody was calling tennis shirts by their proper name anymore. They were now “polo shirts.” Advantage: Ralph Lauren.

Fred Perry didn’t make it much out of England until the late 1990s. In the U.S., it was seen mostly as a straight tennis brand. But eventually, as time went on, buyers at big-name department stores like Neiman Marcus and Nordstrom realized that the label was big among popular Brit Pop musicians like Oasis and Blur and added Fred Perry to their merchandise. The brand became progressively less tennis associated. In 2010, they produced a line in collaboration with Amy Winehouse, and the rebranded Fred Perry got into live music by sponsoring the Dot to Dot music festival that featured (among others) indie bands like The Drums.

Lacoste still has a hand in the tennis world. The brand dresses the American star Andy Roddick along with almost a dozen other pro players. Perry had a deal with Andy Murray — the player that many believe has the best chance to be the first player from Great Britain to capture a Grand Slam title since Fred Perry himself beat American Don Budge at the 1936 US Open — until Murray signed a more lucrative deal with Adidas in 2009. The company still has a tennis collection, but it’s made up of four pieces of clothing: white shirt, white shorts, a white tennis sweater and a white tennis jacket.

But the shirts created by René Lacoste and Fred Perry stopped being about tennis a long time ago. From an advertising standpoint, tennis is the sport most associated with luxury. If you want proof, just open a magazine and find the ad featuring one of the games greatest players, Roger Federer, trying to sell Rolex watches; or look at the companies who sponsor the Grand Slam events: Mercedes, J.P. Morgan, Evian, and Grey Goose. The tale of the two tennis shirts is really a case of commodity fetishism: Lacoste is a luxury brand, so people with money wear Lacoste, and the people who run Lacoste market to their base. Fred Perry clothes are also expensive. Fred Perry has shops in high end/high price shopping areas all over the world and a dedicated following. People associate Fred Perry with rebellion and youthfulness, and that relationship is why the company has thrived for so long without expanding and marketing as aggressively as Lacoste. But at the end of the day it’s the same thing as Coke or Pepsi, Ford or Chevy, Apple or Microsoft: You’re either a Lacoste person or you’re a Fred Perry person. But either way, you’re just wearing a tennis shirt.

Jason Diamond lives in New York. He also lives on Twitter.

Here Is Something Else Parents Are To Blame For

“The extra hours moms and dads are putting in at the office are taking its toll on their family’s nutrition, according to a new study. Research by Temple University’s Center for Obesity Research and Education revealed that greater stress levels for both moms and dads are interfering with healthful eating opportunities. The study found that parents experiencing high levels of work-life stress have one and a half fewer family meals per week than parents with low levels of work-life stress and eat half a serving less of fruits and vegetables per day.”

— The biggest culprit? Working moms, who are of course responsible for all the terrible things that happen to children these days.