When Bad Things Happen to Jimmy Dolan

A tabloid flagrant foul! And: NYU and the Destruction of New York is available at McNally Jackson. (iTunes)

How We Got So "Comfortable With That"

How We Got So “Comfortable With That”

by Jane Hu

“Comfortable” is a flexible term. Any one person’s threshold for comfort can differ from another’s. For the individual, comfort is relative: a heat wave in Edmonton, Canada, say, no longer agonizes after one has endured a heat wave in New York. When a person says “comfortable,” they often mean “pleasant.” Other times “comfortable” translates to just “bearable” or “satisfactory.” While the word “comfortable” doesn’t change, a person’s definition of it can, and usually does, with time — that is, with age and experience. It might happen gradually, incrementally, with constant comparisons between then and now. Comfort itself is relative, its meaning elastic.

The word “comfortable” has been thrown around since the Middle Ages, and the volleying shows no signs of letting up. English speakers have gotten perhaps even a little too comfortable with “comfortable,” with expressions such as “I’m not comfortable with that.” There’s something about “I’m not comfortable with that” that smacks of learned therapy talk — a polite way of talking about our feelings by talking about them obliquely. Or, really, not talking about them at all: “I’m not comfortable with that” is efficiently euphemistic — an efficient way of saying “I’m not comfortable discussing this.” I’m not comfortable with that can mean you disturb my sensibilities, or I feel vulnerable, or leave me alone. It all depends on what “that” is. The earliest employment of the phrase I can find makes it specific. Elvis says in 1957: “I’ll never feel comfortable taking a strong drink, and I’ll never feel easy smoking a cigarette. I just don’t think those things are right for me.” One’s comfort level can indeed change, though Elvis provides us with an especially unhappy example.

You’d think the earliest uses of “comfortable” would be in context of describing physical comfort, but the more metaphysical version of the term precedes the bodily one by at least 50 years. The OED finds the first written occurrence of “comfortable” in Richard Rolle’s religious text English Prose Treatises (circa 1340): “Sothely, Ihesu, desederabill es thi name, lufabyll and comfortabyll.” The phrase credits Jesus’s name as affording spiritual delight. Fifty-ish years later come the first descriptions of physical comfort, which often appear in association with medicines and drinks to aid the sick. For instance, the 1440–1500 Gesta Romanorum (a collection of anecdotes and tales gathered from that served as source material for works by Chaucer, Boccaccio, and Shakespeare) compares “wine comfortable” as “juice to the sick.” Of course, the two meanings, physical and spiritual, are not mutually exclusive: comfort of the body influences comfort of the being.

In regard to the language of comfort, little has changed from then until now (this is rarer than not when tracking the etymology of most Latin-cum-English words). The stability of “comfortable” is partly due to its interpretive expansiveness. The phrase “I’m not comfortable with that” we saw coming into use in the 50s with Elvis has grown since time. That kind of discomfort — about mental and moral unease — has become so definitively attached to the phrase “I’m not comfortable with that” that I have to wonder why, and where, and how?

“I’m not comfortable with that.” One hardly ever says this in reference to a mattress just tested. “I’m not comfortable with that.” See what I mean? The phrase harks back to the initial meaning of comfortable, except rather than spiritual unease, it suggests a more secularized psychological dissonance with a situation or idea. The notion of an “I” being uncomfortable with a “that” could only exist in the modern age, where “I” was seen as a holistic, cohesive, and stable self and “that” could be any abstract thing that the “I” imagines. That tests the integrity of the I. Mattresses, for instance, rarely threaten one’s psyche (though what one does on them might prompt one to employ, “I’m not comfortable with that”).

It makes sense that Henry James — the most delicate wielder of euphemism — would exhaust all the phrasings that involve metaphysical comfort. In The Tragic Muse (1890), “comfort” appears a total of 66 times. One example: “This enabled him to be generously sorry for his companion — if he were the reason of her being in any degree uncomfortable, and yet left him to enjoy some of the motions, not in themselves without grace, by which her discomfort was revealed.” Abstract, right?

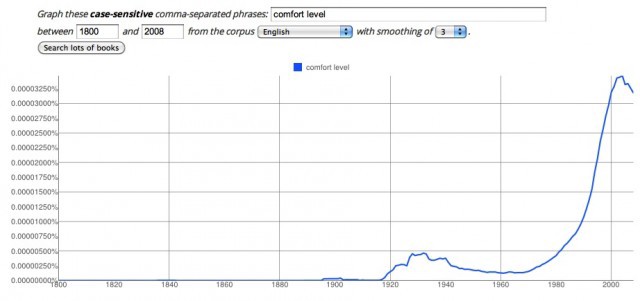

A close corollary to “I’m not comfortable with that” — capturing similar connotations as well as a quality of slang — was “comfort level,” which seems to have entered the popular lexicon from the 70s onward. A William Safire language column titled, yup, “Find Your Comfort Level” examined why in 1988.

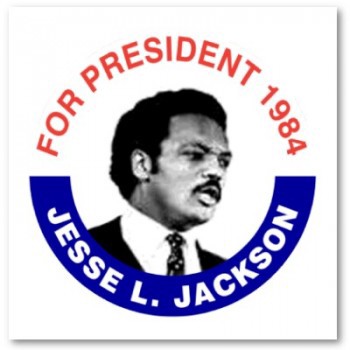

Safire begins his piece by calling “raising the comfort level” one of Jesse Jackson’s “favorite locutions”:

“It’s a mutual growth process,” said Presidential candidate Jesse Jackson of his appeal to white voters, “what I call ‘raising the comfort level.’”

As Jackson suggests, comfort levels can be adjusted. It requires some give and take, but one can eventually adjust to what might, at first, feel new and impossible. Safire proposes that Jackson’s use of “comfort level” exemplifies a change from prior meanings of the phrase:

He is not alone in the use of this soothing phrase. Business Week, reporting on the supersonic Concorde aircraft in 1975, wrote: ‘’Its comfort level is roughly similar to some of the smaller and older jets, although it is much quieter.’’ That sense of physical well-being is still widely used in travel writing, but the meaning has been extended in voguish prose to a relaxation of mental tension.

Again, the physical self and the mental psyche share their claim on usages of “comfortable.” The final sentence depicting “comfort level” might or might not have much to do with the “voguish prose…of mental tension” found in “I’m not comfortable with that.” But a search of “comfort level” in Google Ngrams shows that the expression originates at the same moment Elvis declared his discomfort toward drink and cigarettes.

Safire cites stockbrokers as the first to engage with “comfort level” — a twist, he suggests, on “sense of security.” The piece goes on to trace “comfort level” as it appears first in the financial and business districts, then on Madison Avenue and Toronto’s shopping district retailers, and later in politics. As “comfort level” is represented in the Times, the first articles where “comfort level” appears to describe a psychological baseline (rather than a physical one) begin in 1987. They’re also largely in relation to businesses, investments agencies, and the workplace. (Safire and I probably did the same search, except I had the Internet.)

The speculation throughout Safire’s piece is a titillating, and enabling, thing. Where I had a hunch that “I’m not comfortable with this” stemmed from the discourse of therapy sessions, Safire offers this about “comfort level”: “Where is it from? My first guess was psychiatric jargon.” One statement from the chairman of the Psychiatry Department at George Washing University, however, and this hypothesis is off the table. Safire concludes that “comfort level” derives from “climate control”:

I remember Joe Frederick, president of Long Island’s Sheet Metal Workers Local Union No. 55, using the phrase frequently in the 1950’s: “You can’t get a consistent comfort level without warm air heating.”

Safire does not attempt to make a connection between “I’m not comfortable with this” and “comfort level.” I assumed an association between the two, but would he have? Impossible to tell from his article. And does it really matter, finally, if we pinpoint whether “comfort level” came from psychiatric discourse or “climate control”? From the sporadic guesses and clues Safire tugs into his argument, it doesn’t really feel like he all that much cares about claiming or confirming the phrase’s ultimate origins. What matters more is how we explain why some phases catch and keep on.

***

Safire begins his piece with the appeal pitched by Jackson, a black Presidential candidate, to white voters: “It’s a mutual growth process… what I call ‘raising the comfort level.’” It’s a minority figure’s call for the majority to shift their perception on what is “bearable” and “satisfactory,” if not “pleasant.” In 1990 (two years after Jackson’s run), the Times used “comfort level” in an article titled, “Harvard Law School Torn by Race Issue.” The title is deceptive as the piece is about a declaration by Derrick Bell, a black male professor, saying he would stay off the job until Harvard gave a black woman tenure. A black female student is quoted:

They have had years to find a black woman, but they just want to keep the status quo, what they call the comfort level of white men. The fact remains that we are getting only a white male corporate view of the law. We need black women mentors to tell us what it is like out there when we join a firm and start trying to get clients.

Same idea as Jackson’s situation, except add sexism on top of racism to the equation. You know from which side.

Ten years after Jackson’s hope of “raising the comfort level,” and a white woman uses the same euphemism to describe her reluctance in sending her daughter as one of the two white students in an all-black North Carolina charter school:

“I’m not going lie to you and say it does not test my comfort zone,” Mrs. Premont said. “But I knew enough about the school to overcome any comfort level issues that I had.”

My discomfort here isn’t caused by Premont’s judgment of the school’s tenor, it’s with using something like “comfort level” to describe it. Another piece around the same time uses phrases like “comfortably integrated to largely black” to describe a neighborhood that is actually striving for racial balance. I understand: sometimes the language grinds against the act.

The phrase of course isn’t isolated to issues of race. “Comfort level” often turns up when issues of gender inequality or scenes of sexual anxiety are being discussed, particularly in connection to businesses and institutions. In 1987, the Times used “comfort level” in articles about sexual politics in the office and one about merchandizing of fruit: “It has to do with the comfort level of the buyer. The buyer has to be comfortable knowing what the product is, who would buy it, what temperature it needs, does it require special handling.” OK. See? Comfort is relative. In the article on sexual politics, the men are uncomfortable because they feel threatened by women in the office. The women are uncomfortable because they feel diminished by men. Maybe, yes, ok? But when you have the luxury to maintain a rigorous comfort level about where your fruit comes from? That might better illuminate the present-day burgeoning of “I’m not comfortable with this.”

Like Jackson’s white voters, people who are able to dissect the origins and packaging processes of their fruit have a choice. The former might be race based, and the latter class based, but both have, in a word, privilege. They’re able to sense and articulate their discomfort because they have the option of remaining as they are, which is comfortable. The world is actually trying at all times to make their lives — those of the most comfortable — even more so. “Would men feel more comfortable shopping at drugstores?” asks a 1995 Times piece about the crises of emasculation men face whenever near cosmetics.

She attributes the male comfort level to the pharmaceutical look of the store and the packaging, the no-fragrance policy and the convenience of ordering by mail. She says one “older gentleman” in Italy orders 50 shaving creams at a time.

Who knows, it might be the most privileged — in terms of sex, race, and class — who feel threatened the most, who sense the greatest discomfort. Is it because they expect their comfort levels maintained at all times — that the world always to yield to them? Another article theorizes that only in America do supermarkets aim so desperately at making their clients feel at home:

to transport you into a place of chromatic familiarity, a ‘high comfort level,’ for the same reason that the music is slowed down: rather than try to rouse us from our coma, the soothing pastels and assuaging complexion seek to keep us in our drowsy 14-blink, 60-beat state. Slowly. More slowly. More time. More purchases. Slowly, now. Frozen spicy popcorn shrimp. Sleepy, now. More slowly.

The mood of this scene begins to sound something like a therapy session. Indeed, a company’s analysis of their clients’ comfort level begins to feel like a psychologist’s assessment of her patients. Get them at their most comfortable — their most vulnerable — and then get them on your team. The speech act “I’m not comfortable with that” could bring everything to a halt, so best to ease people in by putting them at ease. Comfort slides gradually, incrementally. Slowly. More slowly. More time. Sleepy, now.

Related: Histories of ‘Schadenfreude’ and ‘Blackmail’

Jane Hu is uncomfortable with the term ‘precarious.’

Make Crap At Home

If you are for some reason so inclined, here is how to make a Big Mac in your own kitchen. Although I have to think that no matter how closely you follow the instructions, you’re never going to attain that particular flavor that is associated with the existential despair of actually being in a McDonald’s and ordering a Big Mac. You know the taste. It’s a mixture of resignation and umami. [Via]

Hotel Gets Publicity

“Guests at a hotel in Cumbria may get a shock next time they reach for a copy of the Gideon Bible from their bedside cabinet. The Damson Dene hotel near Windermere, Cumbria, has decided to replace the book — which is traditionally stocked by British hotels — with copies of the erotic novel Fifty Shades of Grey.”

Face-Eating Goes Global

“So what do you think? Was this a real ‘zombie’ attack? Or did the man do it just because he’d had a few too many at lunch?”

Hiking The Grand Canyon In A Day

by John Ore

Signs posted at the rim of the Grand Canyon warn you not to attempt to hike to the river and back in one day: it’s too strenuous, and you need to be prepared with food and a gallon of water per person. Apparently, there are several deaths (especially in the summer months) and 250 rescues made each year, so the National Park Service is serious about this. Typical warnings exhort: “DO NOT attempt to hike from the rim to the river and back in one day, especially May to September.”

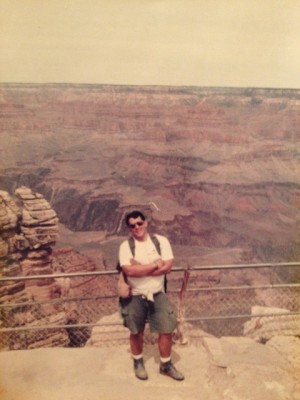

I arrived at the Grand Canyon in late March. It was Spring Break, 1990.

A couple of fraternity brothers and I had decided to drive from Berkeley to the Grand Canyon, stopping and camping along the way as time and our whims permitted. A loose itinerary included Death Valley, Las Vegas, the Natural Bridges National Monument, and really anywhere else that looked at all interesting in our Thomas Guides. “Camping” was a bit of a relative term: we threw everything we could think of in the back of a small Toyota pickup without much thought given to space or utility: we had a huge family tent that looked like it was from the 1970s, overstuffed sleeping bags, army surplus backpacks, boda bags and canned beans, and, of course, beer. (I later found out that someone had brought a 9mm handgun.) Three of us jumped into an old Volkswagen Scirocco and followed the other two in the pickup off into the Sierras one evening only to discover that our preferred route across the mountains was still closed for the winter. We made the detour and drove through the night. Around 6 the next morning, we watched the sun come up near Mono Lake as we pitched the tent in a deserted campground. We dozed off for a few hours, but woke up when a park services ranger came by to oust us. It turned out the campground was closed for the season. This would, it turned out, become a theme of the trip.

***

Three days later, we arrived at the Grand Canyon under darkness, resigned to having to wait until morning to actually see it. We’d camped at Furnace Creek in Death Valley, done a few half-assed day hikes, and stopped in the Arizona desert to fire off a few rounds from the 9mm (the ammo came from a Kmart somewhere, where we also bought some fishing licenses that we’d never use).

The South Kaibab Trail starts 7,260 feet above the Colorado River on the south rim of the Grand Canyon, and runs about 5 miles to the Phantom Ranch campground on the floor of the canyon. Three miles in, you’re still a mile above the river at Skeleton Point, where you are advised to turn around if day-hiking. From there, it’s a steep vertical descent to the river. Three of us — Scott, Jeff and I — decided that we were going to hike down to Phantom Ranch, spend the night at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, and hike out the next day. Our two other companions dropped us off at the trailhead, opting out of the hike.

We were just college jerks, ill-prepared and poorly outfitted for our expedition. It was late March, but there were still patches of snow here and there on the canyon rim. We were wearing shorts and t-shirts, maybe with a sweatshirt tied around our waist, each hauling a sleeping bag, canteen, and perhaps a can of baked beans. We didn’t even bring a tent.

Hiking down, the goal of our trip finally came into focus: as people say, you don’t quite believe the Grand Canyon is real because its scale is off the charts. It’s so huge you have a hard time believing what’s right in front of your eyes. It was a warm, partly cloudy day, and we were fueled by our enthusiasm and the sheer vastness of the canyon that was swallowing us. We set a leisurely pace, stopping to take pictures along the way, and eventually made it to the suspension bridge over the river by mid-afternoon. After a refreshing dip in the Colorado River, watching rafting tours drift by, we made our way to the Bright Angel campground to grab a campsite. Understandably more spartan than the crowded campground in the village at the canyon rim, Bright Angel was tucked into a small ravine off of the river on the way to Phantom Ranch, with small campsites roughly demarcated off of the trail. It was pretty empty. Perfect for an overnighter, we envisioned sleeping under the stars at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. We set up camp and started a small fire to cook with. Then a ranger came by.

***

There are three main “Corridor Use Areas” below the rim of the Grand Canyon, all of which require backcountry permits for camping. The Bright Angel campground is one of them. Apparently, people apply for permits weeks, months, even years in advance. With the benefit of the internet, you can discover this in about 5 minutes. With the benefit of hindsight, you could probably have discovered this by doing a tiny bit of research 20 years ago. As I said, we were just dumb-ass college kids. At today’s prices, it would have cost the three of us $25 total to camp at the bottom of the canyon overnight.

The ranger asked us for our permit, which of course was the first time we’d heard of such a thing. Naturally, we simply asked if we could buy a permit from him. This was an honest request; it didn’t even dawn on us to attempt a bribe, and we were naive enough to think that rangers sold permits like train conductors. His response was very matter-of-fact: you could only obtain permits at the rim of the canyon, they were absolutely required, and people waited months to get them. Then he told us we’d have to leave. Not just the campground, but the Grand Canyon. (As a result, by the age of 20, I’d officially been kicked out of the Sherman Oaks Galleria, the City of Beverly Hills, and now the Grand Canyon.)

It was about 5. We protested, using the day-hiking warnings as our defense. He told us we could rest, get some food and water in us, then hit the trail. We’d be fine, he said. We briefly considered finding someplace secluded along the river to hide out for the night, but we were so frustrated at having our Grand Canyon experience spoiled by bureaucracy that we just wanted the Hell out. Within an hour we were headed along the river to the Bright Angel Trail. We’d planned to use it as our exit the next day anyway, reasoning that it was less steep than the South Kaibab Trail and its trailhead was in the village, where our friends were camped. But it was also almost twice as long as the South Kaibab Trail. (My father would later remark: “I would have told the ranger to go screw himself, and make them bring in a helicopter if they wanted to arrest us.”)

Starting our ascent, I immediately knew it was going to suck. My knees were still shaky from the 5-mile-plus descent, I wasn’t in the best shape, and we had 9 miles to go. Uphill. At first, there was a sense of camaraderie, the three of us sort of shrugging our shoulders, viewing this as just another byproduct of our loosey-goosey approach to the trip, an adventure, and muttering about how fucked we were. After an hour or so, we fell silent and trudged along. Later, as dusk came, my legs started cramping up. Jeff and Scott would take turns pounding my quads and calves with their fists to try to loosen up the cramping muscles (and probably also out of frustration at my slow progress). Halfway up the trail, under darkness, we stocked up on water at the Indian Garden campground while I tried — in vain — to convince my march comrades that we could sneak into the campground and spend the night. Instead, we pushed on in the dark.

The worst part — well, one of them — about hiking in the dark was the sensation that you were walking in place, like on a treadmill. The trail and incline and switchbacks barely changed in the cones of our flashlights, and the lack of discernible progress was exacerbated by the dark mass of the rim just sitting there outlined against the starry sky: it never changed, never drew closer, and never went away. Several times I sank down on the trail — as much from desperation as fatigue. So we just stopped on the trail, lit an impromptu fire, and cooked our beans in the can to rest and break up the monotony. I’m sure this was illegal, but we didn’t care. I wanted to unroll my sleeping bag right there. Scott and Jeff just wanted out.

After five hours, we ran out of water, and our little unit of three fractured. Scott, convinced that he could find a shortcut to the top, took off straight up the hill despite our protests that he had one of our two working flashlights. We’d see his outline on a ridge, we’d yell “Scott!”, he’d reply “What?!?!?”, and we’d ask him what he was doing. No answer. Then we’d repeat the call-and-response with the same results. Eventually, we gave up. Jeff and I marched on, convinced Scott was going to fall off of a cliff with the keys to the pickup. 20 minutes later, I spotted a patch of snow glowing in the moonlight above the trail, and made a beeline for it (I was thirsty). Jeff started to scream and curse me, thinking I was taking off like Scott had — and because I had the only remaining flashlight.

***

Jeff and I would emerge at the Bright Angel trailhead at 12:30 am, about 6-and-a-half hours after we’d started hiking out of the Grand Canyon and more than 12 hours since we’d first glimpsed the canyon from the South Kaibab trailhead. We found Scott at the top, waiting for us. We were too tired to be pissed at him, and wandered into the Bright Angel Lodge where they gave us orange juice at the closed bar after listening to our story. We even managed to hitch a ride back to our friends’ campsite.

The next day, Scott, Jeff and I left the Grand Canyon as soon as we could. Our other two friends stayed, but we’d had enough. We headed towards Monument Valley, Utah; the three of us crammed into the cab of the pickup, dazed and sore. We set up camp alongside the road somewhere near Natural Bridges National Monument, convinced yet another ranger would come along to roust us. Upon looking at the map and discovering we were a two-day drive from Berkeley, we lost our resolve and started on the long drive home with nothing but an audio book about Abraham Lincoln and Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma on cassette. Both of which are super creepy to listen to while driving Route 50 through Nevada at 2 in the morning.

Previously in series: Portraits From A Cross-Country Road Trip, Fly Fishing The Universe and A Chat With A Person Who Has Been To Disney Parks 40 Times

John Ore hasn’t been back to the Grand Canyon since. Top photo courtesy of eGuide Travel.

A Takedown of the Berlin Holocaust Memorial

I’ve never heard anyone say an ill word about the Berlin Holocaust Memorial! And yet here is a fairly thorough take-down.

The title doesn’t say “Holocaust” or “Shoah”; in other words, it doesn’t say anything about who did the murdering or why — there’s nothing along the lines of “by Germany under Hitler’s regime,” and the vagueness is disturbing. Of course, the information is familiar, and few visitors would be unaware of it, but the assumption of this familiarity — the failure to mention it at the country’s main memorial for the Jews killed in the Holocaust — separates the victims from their killers and leaches the moral element from the historical event, shunting it to the category of a natural catastrophe. The reduction of responsibility to an embarrassing, tacit fact that “everybody knows” is the first step on the road to forgetting.

That’s certainly true, the way history works: in 200 years, will people even be sure what the Holocaust was? While they are guzzling Brawndo.

What Is Mike Bloomberg Wearing at Mogul Fest?

So, again, where is our mayor? He’s had no public schedule for three days in a row & he’s calling into his radio show.

— Mike Grynbaum (@grynbaum) July 13, 2012

So it turns out @MikeBloomberg is at MogulFest in Sun Valley, Idaho. Here he is looking thrilled about it: bit.ly/M6Rzgz

— Mike Grynbaum (@grynbaum) July 13, 2012

Pretty sure he’s clad in head-to-toe Loro Piana. MAYBE Cucinelli. But you know, he’s from Boston, so it just might be high-end JC Penney.

"I think the following 15 rape jokes are hilarious"

Well, Kate Harding went and made a list of rape jokes that she considers to be actually funny. (At least one of them did indeed make me laugh!) TRIGGER WARNER: Dane Cook is on the list. (Double trigger warning: “racist v. rapist” in this one. Complicated.)