Chuck and Jimmy

And now they’re dead.

As a certain kind of America passes away so that a meaner, uglier one can be born it is still something of a surprise when the remnants of the earlier era shuffle off, if only because it reminds us that they walked the same earth as we did (and are lucky to get off of it before the real horror comes down). There’s plenty to read about the passing of Chuck Berry and Jimmy Breslin if you are so interested — and you should be: We’re busy murdering the word “iconic” by applying it to anything that has lasted longer than ten minutes, but these are two actual icons, legends who spawned legions of imitators, men whose innovations were so profound that it is impossible to notice their influence in the world anymore because even those they influenced have themselves inspired imitation —but here are a couple of places to start.

- Chuck Berry Was the Sound of 20th Century America

- Legendary Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin dead at 88

These Times obits (Berry, Breslin) are also worth a read, and here are collections (Berry, Breslin) of their greatest hits.

Skipping Ourselves To Death

Apologies to Rod Serling

[We dissolve to a shot looking toward a metal spacecraft, which sits shrouded in darkness. An open door throws out a beam of light from the illuminated interior. Two figures silhouetted against the bright lights appear. We get only a vague feeling of form, but nothing more explicit than that.]

FIGURE TWO: So they were the most advanced civilization in the history of their planet, but now they’re all gone?

FIGURE ONE: Yes. If they had avoided some of the obvious mistakes, they could have ruled the universe, but success always contains within it the seeds of its own destruction.

FIGURE TWO: What happened?

FIGURE ONE: Well, the usual issues that complicate things for a species of this sort… avarice, jealousy, a lack of foresight… They told themselves they were living in a meritocracy, when really the richest amongst them had grabbed control of their political system and convinced many of them to go against their own interests through misguided tribalism and irrational fear. Meanwhile, they engaged in a sustained campaign of planetary destruction even way past the point when it had become clear that the damage they were doing was unsustainable.

FIGURE TWO: Interesting. And they weren’t able to save themselves through technological innovation?

FIGURE ONE: Technological innovation, ironically, is what brought the whole thing down. The rich can only keep their boots on the neck of the poor for so long. Revolutions happen and then society’s wealth is reallocated, for a brief time at least. The bad blood is washed away and a new order exerts itself. They could have survived it. The pillaging of their planet was nearly beyond repair, but they would have eventually come up with some sort of scientific solution, even if it had to be imposed on them after an emergency. This was not a race whose extinction was inevitable by any means.

FIGURE TWO: So… why couldn’t they work together to solve it? Surely they saw what was happening. They had mastered the atom, after all. What made the whole thing fall apart?

FIGURE ONE: Instead of focusing on making their world more equal for everyone or fixing their environmental issues, their best minds came together to ensure that they were no longer subjected to the tyranny of passively enduring sixty seconds or less of theme music while they sat on their couches and had televised content streamed at them hour after hour, hour after hour until they wasted away. Hour after hour… hour after hour… hour after hour…

[The camera slowly moves up for a shot of the starry sky, and over this we hear the Narrator’s voice.]

NARRATOR: The tools of conquest do not necessarily come with bombs and explosions and fallout. There are weapons that are simply [SKIP OUTRO]

Christopher Willits, "Clear" (Boreta Remix)

Winter is over, in a strictly technical sense

It’s spring. Nothing will get better — in fact, it’s all going to get a lot worse — but at least the birds will be chirping and the weather will warm up. So there’s that. And here’s this, which is pretty enjoyable. Enjoy! It’s spring.

New York City, March 16, 2017

★★★ The schoolyard was still icebound and the sidewalk snowbanks, yellow-stained, pressed in on the streams of parents and children coming from opposite directions toward two different doorways. A pair of wide-axled strollers locked up at cross purposes in the turbulent flow. Trembling rivulets of meltwater covered the glass side of the Apple Store. A man pointed a cameraphone at the building from across the street as the roof kept shedding ice. One flat chunk came flying and flipping down to land with a light crunch outside the protective rope. Out on Broadway, something fell heavily on a totally unprotected patch of pavement by the corner of the furniture store. The sun was warm and the air was not. Cleared snow lay in thick broken slabs. A canopy stood swaybacked with its unshed burden. At rush hour, some of the puddles were all liquid water, free of slush. The halal cart, missing at dinnertime the night before, had found a place to park.

The Wheel And The Knife

The ecstatic and drastic rituals of Russia’s radical Christian sects.

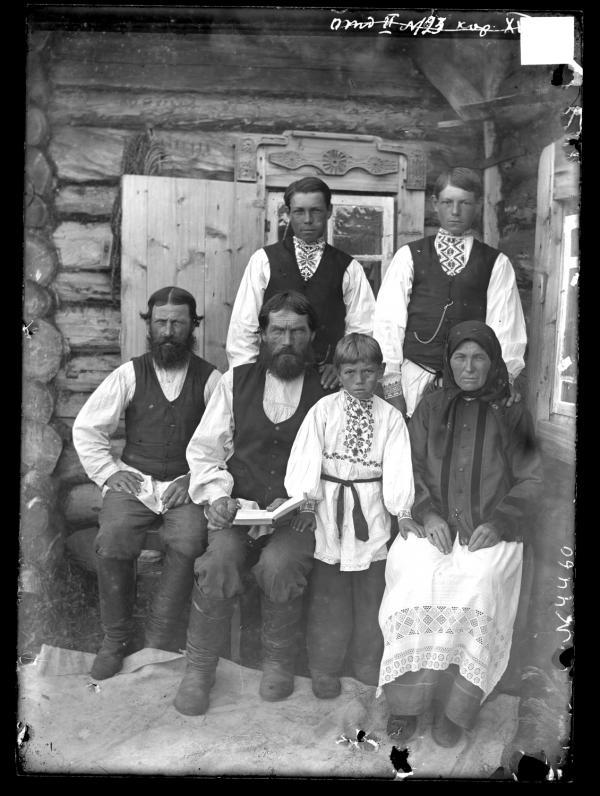

Whether at home or on the road, a true servant of God must always be alert to the snares of the devil. The year is 1717. The Russian Orthodox monk Antonii is on holy pilgrimage. Weary from his journey, he stops in a home for wayfaring strangers outside the town of Uglich, north of Moscow. There he meets two widows, Kapetolina and Avdotiia. From their conversation he realizes that they must be heretics. He pretends to be a fellow schismatic, and begs to meet their teacher. They refuse — it is forbidden — but they promise to ask his permission in the future. Antonii thanks them for their consideration. The next day he denounces the two old ladies to his superior, the archimandrite.

An investigation begins; arrests are made. Gradually, the truth emerges: the women belong to a sect, which has long met in secret. Its leader is a former soldier who says he is Christ. Its members include a farm worker, a cloth-seller, a merchant of butter. They do not drink or marry. They say they do not fornicate. Instead, they meet at night in secluded houses, sing hymns and dance to exhaustion.

The 1717 investigation marks the entry into official history of a group that called itself God’s People, but which was widely known as the Khlysts. In their rituals and beliefs, the Khlysts tried to solve an old puzzle: How to live in a world without God, where holiness is missing and even his prophets are silent or far away? Their answer was to pursue ecstasy, everywhere, even at pain of death. In time, the Khlysts gave rise to a rival, or offshoot sect with very different ideas. These were the Skopts, and they believed that the way to holiness lay in extreme renunciation: not just of sex, but of the very organs that mark sexual difference. Now, their practices might seem grotesque or obscene. But they carry a lesson, of how hard it is to square belief with life and how much we might need to give up if we want to make life paradise.

This was the question posed by two Christian sects, the Khlysts and the Skopts, which operated in Russia several centuries before the revolution of 1917. Both were heretical offshoots of the Orthodox Church. One was accused of leading its followers deep into the woods of sexual profligacy. The other publicly urged its members to engage in self-castration. Both were frequently persecuted by the state, and widely despised by the people.

The story of the Khlysts begins in the 17th century, in the province of Kostroma, with a peasant (and perhaps, a runaway soldier) named Danila Filippovich. Unusually for the time, Danila could read and write, and he knew Scripture. He travelled across Russia and preached. One day in 1645, on a hill in village of Gorodina in the Province of Vladimir, the godhead descended upon Danila in his fiery cart, trailed by angels and seraphim. Henceforth, he regarded himself the Living God. He issued commandments like Moses on Mt. Sinai. He announced that there was no teaching but his. From now on, the only book that mattered was the “dove-like” book written in the heart by the Holy Spirit. To prove his point, he took all the books he owned, put them in a sack, and threw them in the Volga River.

After fifteen years of wandering, Danila came across a spiritual son in the manner of St. Paul. His name was Ivan Suslov. According to legend, his parents were both a hundred years old when he was born, and they were so poor they used a broken pig trough for a cradle. When Suslov was thirty-three, he met Danila, who named him his Jesus Christ. He worked miracles. Twice he was crucified, and twice he rose from the dead. The second time he was also flayed, on the order of the czar. When returned to earth a young girl covered him in a sheet which stuck fast and became a second skin. He levitated, and he flew. With Danila, he visited heaven three nights in a row. He was buried in the village of Kriushino in the province of Kostroma.

Suslov and Filippovich gathered many followers. After their deaths (or, ascensions) those followers recruited followers of their own. They called themselves the Christs, or Khristy. Outsiders, noticing their habit of flagellating themselves, nicknamed them the Whips, or, in Russian, Khlysty. The Khlysts believed that Jesus was born like any other man. He was no different from other men until the age of thirty, when the Holy Spirit anointed him and made him God’s son. And if the Holy Spirit could enter one man, it could enter others as well, even women. It stood to reason then that there could be many Christs, and many Mothers of God. The Khlysts’ aim was to bridge the world of the supernatural and the present, to merge divine time with our own, but hardly any of them would admit to it in public.

The great Russian folklorist Andrei Sinyavsky has called the Khlysts the most interesting, as well as the most impenetrable, sect in Russian history. This is because the Khlysts kept the true nature of their beliefs hidden from the profane. Novices, upon being accepted into the sect after long trials, had to take a special oath: “I vow to keep secret all that I shall see and hear at meetings, never sparing myself, never fearing the knout, the stake, the sword or any other torment!”

The Khlysts believed that lying was a sin, but only when the lie was committed before God. To conceal themselves from persecution, they became masters of dissembling. When missionaries denounced the Khlysts to their face, they acted horrified that anyone could believe such horrible untruths. When priests asked, “Have you sinned?” the Khlysts would reply: “I am guilty before you. Father.” When the priests gave them wine to drink at Mass they would keep it in their mouths and wait until the service was over to spit it out.

The Khlysts called their communities “ships” or korabl’ because they felt themselves to be abandoned on the sea of the profane world. Each ship had a helmsman. If it was a man, he was called their “Christ.” If the community was run by a woman, she was known as the “Virgin.” They abjured onions and garlic, for they were thought to mask the odor of sanctity which they detected in one another. They avoided meat, because it was the product of copulation. And they avoided the potato, believing it to be the true shape of the fruit with which Eve tempted Adam.

For all its prohibitions, the core of the Khlysts’ religious practice was about a conscious pursuit of ecstasy. They called their main rites radenie, a word that means zeal, but also connotes fervor, and joy. Radenie were typically conducted at night, in a cottage far removed from neighbors. Here, the Khlysts sought God in dance. In ones or twos, they spun like dervishes, twirling until the candles in the hut blew out and they collapsed exhausted, drenched in sweat. Sometimes they would gather together in larger numbers for ‘ship,’ or ‘round,’ dance in a ring around a vat of water. As they danced, the Khlysts spun in a circle and flagellated themselves. Suddenly, a whirl would appear in the water, a sign that the Holy Spirit had appeared. Sometimes the water would boil and bubble, and the baby Jesus would appear in the steam. Then the Khlysts would take the water home and consume it, getting “drunk” on what they called “spiritual beer.”

Music was a mainstay of Khlyst worship. They had a gift for composing hymns. According to a Khlyst saying, “A song (pesenka) is a ladder (lesenka) to God.” Their music was strange and haunting. It had something in common with the music of American Shakers and shape-note singers. Frederick Cornwallis Conybeare, an English scholar of religion, wrote of once seeing a group of them in procession on the solitary plains between Yerevan and Mt. Ararat. He called it “the most stirring devotional music I have ever listened to, adding “No one who has encountered them will forget their deep-set intensely gleaming eyes, their spare emaciated frames, their reposeful manner. They seem to have dropped out of another world into this one.”

In this world though, the Khlysts were treated with constant hostility and suspicion. Their night-time rituals gave rise to many unsavory rumors. It was thought that they engaged in group marriage, and that their radenie ended in orgies. Numerous police searches and raids failed to turn up anything salacious. But the Khlysts varied — every ship was governed by its own Christ, and each Christ obeyed the will of the Holy Spirit. Sometimes this meant that their worship veered off even further from the mainstream.

In Ivan the Fool, Sinyavsky relates how in the mid-19th century, “a 29-year-old ‘Christ’ by the name of Vasily Radaev confessed that he had slept with all of his female followers.” During an interrogation he explained, “I copulated with them all, but I did not allow others to, I copulated with them not of my own free will, but by the will of the Holy Spirit.”Radaev seems to have stumbled upon the old antinomian principle that the only way to fight sin is with sin. The Skopts, an offshoot of the Khlysts, came to the exact opposite conclusion. They made the suppression of sexuality the absolute center of their belief, and they pursued this goal by means that have inspired lasting revulsion, as well as misunderstanding.

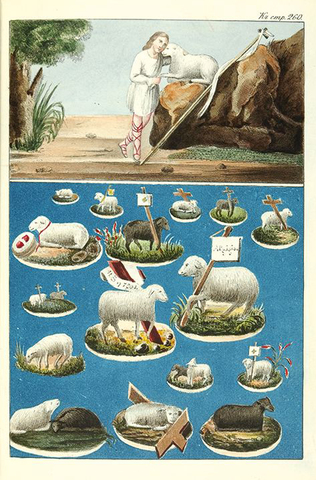

The origins of the Skopt sect are unclear, but they seem to have been an offshoot of the Khlysts, from whom they borrowed the practices of the radenie and the round dance. To this they added the radical principle of castration. The Skopts (their name means ‘the Castrated Ones’) believed that in Paradise, the first people created by God were without sex. Breasts and genitals were only added to the human form after the Fall. They were thus literal fruits of Satan, deformities, and as such, had to be cut off.

Like the Khlysts, the Skopts practiced their faith in secret. Their symbol was the dove, their patron was St. George, and their instrument was the knife. They called castration “mounting the white horse” or “receiving the great seal.” There were greater and lesser seals. To have one’s nipples and testicles excised meant becoming an angel. Losing the breasts and penis as well made one an archangel.

Before accepting castration, a Skopt prepared for death by saying farewell: “Farewell sky, farewell earth, farewell sun, farewell moon, farewell lakes, rivers and mountains, farewell all earthly elements.” If they survived the procedure, which was conducted without anesthesia, they would find themselves reborn in a heavenly body.

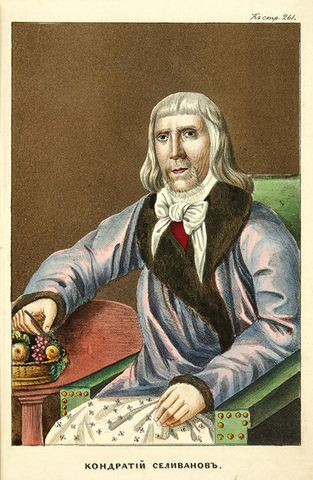

The Skopts’ first recognized prophet was a man named Kondratii Selivanov. He was a peasant, born sometime around 1732 in the province of Orel. In his youth, he belonged to a Khlyst ship headed by a Virgin Mother named Akulina. A prophetess named Anna recognized the young beggar as the true son of God. Selivanov began preaching, but he had trouble persuading Akulina’s congregation to accept castration. So, in his words, he “set out across the damp earth,” showing everyone purity. In time, he acquired one disciple, then many.

Eventually, he had so many that the authorities became alarmed. Selivanov’s disciples were exiled to Riga. He was imprisoned in Irkutsk. There, he began to preach that Akulina had actually been the Empress Elizabeth, in disguise, and that he was her son, the Tsar Peter III, escaped from the grave. This was treason, and it earned him the knout.

But then, a reversal of fortune: Peter III’s son, Paul ascended to the throne. He revered his father. He even crowned his skeleton before crowning himself. Then he summoned the Siberian stranger who claimed to be his father to St. Petersburg for an audience. It is unknown what they discussed in their meeting. According to one rumor, Paul asked Selivanov if he was his father. Selivanov replied that if Paul would take up his cause (castrate himself), he would become his spiritual son.

The Emperor did not castrate himself. Instead, he had Selivanov confined to an asylum. But soon the Emperor was dead, and a new Tsar — Alexander — was on the throne. Alexander freed Selivanov from prison. He went to live with some wealthy merchants who followed his faith. One of Alexander’s ministers, a chamberlain named Alexei Elyansky, took a special liking to him. He conceived of a plan to turn all of Russia into a single Skopt ship. State prophets would direct every branch of government. Elyansky and twelve other castrated holy men would command the army. The Tsar would be advised at all times by Selivanov himself. Special prophets would serve on battleships, “so as to offer the captain advice with the voice of heaven before going into battle.”

The tsar rejected Elyansky’s scheme, and had him confined to a monastery. In 1805 though, Alexander visited Selivanov before leaving for his first campaign against Napoleon. Afterward, persecution of the Skopts largely ceased; they were warned not to engage in any more castrations, and not otherwise harmed.

Selivanov died in 1832. For decades, his followers refused to accept that he was dead, awaiting his return. Despite their inability to procreate, their numbers continued to increase. At their height in the late 19th century, they may have had as many as 100,000 followers. They became known for their probity, frugality, and devotion to hard work. Some managed farms. Others lent money, but never to other members of their faith. Many grew rich. They lived as model citizens — honest, respectful, and careful not to draw too much attention.

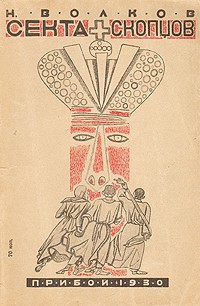

Still, they were persecuted by the government, church, and society. Some were exiled to Siberia. Others fled to Romania, where they dominated the horse-cab business. In Russia, they were tried in the courts, courted by missionaries, studied by ethnographers and denounced by the bishops. Though they inspired disgust in many, they also elicited a curious fascination. The most sympathetic treatment of the Skopts came from members of the revolutionary left.

The radical opposition had long felt a kinship with the Skopts and other schismatics. Heresy was the Russian way of revolt, the thinking went; breaking with orthodoxy was the first step in breaking with the Tsar. Populists, nihilists and socialists all sent representatives to the different sects. One of the most perceptive students of the Skopts, was the Bolshevik Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich. He went on to become Lenin’s personal secretary and helped set the Red Terror in motion. Later still, he helped organized a museum of atheism in Moscow where a display on the Skopts featured as a central exhibit.

They make a strange pair: the hardened Bolshevik, using terror to usher in modernity, and the archaic-seeming sect mutilating their bodies to remove the taint of original sin. In their own way, the Skopts had embarked on a social experiment no less radical than that of the revolutionaries. In pursuing castration, they removed the great stumbling block to utopia: desire. After all, what makes us more selfish than love? The Skopts redirected the passion reserved for children and lovers to the community as a whole — they lived in communes, not families, and held property in common. Their kin were determined by belief, not blood.

In other places and times, this would be known as communism. Across the centuries, the Khlysts and Skopts ask, is it better to live for joy or purpose? Dance, make love, get drunk on the joy of the body say the Khlysts, to the sound of whips. Mortify the flesh, punish the body, and be free, say the Skopts, to the sound of bells.

New York Public Library's Rose Reading Room, South Hall

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

I’d been resolved not to fall into another of those situations with neighborhood baristas, those relationships of daily small talk and incremental intimacy, where before you know it, it’s plain too late to ask their name. So months back — maybe even a year ago? — I’d introduced myself to you. I’d tried to remember, I’d repeated it to myself, but yours was an unusual name and — I’m sorry — by the next day it had escaped me. A “k” in it, somewhere? That’s all I’ve got. I have a weird name too. Yours, however, did not have the retentive advantage of being shared by a character in a global cultural phenomenon.

Here was the thing that made seeing you a suckerpunch: today, earlier this afternoon, walking through the subway, you’d appeared quite firmly and clearly in my head. You, a person I barely knew and hadn’t seen or thought about in a year! I’d felt a surprise at the thought of you, a what are you doing here? So I didn’t believe it, when, an hour or so after this, I looked up in the South Hall of the Rose Reading Room of the New York Public Library and there, a few tables over, was someone who looked exactly like you. I stared so hard that I felt the person opposite me — an elderly man peering down his spectacles at a laptop which bore a union jack sticker — cast a reproving glance. Like, stop gawping young lady and get to work. I kept gawping. They looked exactly like you because, yes, they were definitely you.

You had the same butch haircut I remembered. Red flannel shirt. You were hunched over a textbook with a yellow highlighter in hand and I wondered what you were studying to become or what you already were, other than the person that had made me a soy matcha latte most mornings for a period of five or six months. We’d shared a little history, minor dramas, all of which had been intensified by me being the only one in the place between the hours of 8am and 11. Which, of course, I now realize, is probably why it shut down.

There’d been the guy on the bike, do you remember him? It was a morning after snow, the roads slushy with it, and I’d looked up out the window and watched him fold right off his bike into the tarmac. And just lie there, on his side, like a bug. You and I had met eyes in surprise, slight horror, then both rushed outside. We’d helped him up, got his bike locked up, called his work, got him in a cab to a medical clinic and the whole time he’d barely said anything, stunned with shock or pain. His bike stayed there, locked up outside, for weeks, causing me to fret each time I saw it. There was him. And then there was that guy who’d peevishly swiped a napkin one summer morning, remember him? You’d yelled at him fruitlessly as he made off with it down the street, sauntering. It was the first time I’d seen seen the waving of white fabric as an antagonistic gesture.

Now, I wanted you to look up and see me, but also not, because there would be unavoidable and false romance in the moment. I thought of that scientific study that claimed that if a pair of strangers did a certain sequence of things, culminating in them staring into each other’s eyes for four minutes, they would, apparently, fall in love. I felt that if you, two desks away, were to raise your gaze and meet my eyes under the pink-flushed clouds of these ancient high ceilings, it would almost as excruciating as staring into a stranger’s eyes for two hundred and forty seconds. Because if you looked up, you’d recognize me, probably, and you’d see me writing and the excruciating thing would be you not knowing that I was writing this, about you.

Awlcast Episode Nine: Handwashing

Talking hygiene with Lindsay Robertson.

How many times per day do you wash your hands? Do you wash your hands after riding the subway? When you’re on the subway, do you touch the pole? Do you cover your mouth when you sneeze, using the crook of your arm rather than your dirty hands? How often do you sanitize your phone? Do you carry Purell with you? Do you wash your hands after you shake hands with new people? Are you self-conscious about how much you wash your hands? Are you using non-antibacterial soap? When was the last time you got sick? Do you know how contagious norovirus is? Do you take probiotics? We discuss and overthink all these questions and more on this week’s episode of the Awlcast, with our special guest, “a person whose hands are almost always clean.”

Eight Weeks Later

A reflection in verse

Every week that passes makes it easier to forget

That once there was a time you weren’t always this upset

You’re not yet at the point where all your anguish comes pre-reckoned

But still, when awful news drips out at every single second

It feels almost ambient, like water or the air

You can’t recall an age when all the terror wasn’t there

It’s only human nature that eventually you’ll settle

And not spend half your life in demonstrations of your mettle

It’s hard to wake each morning when the world must be resisted

You get exhausted trying to be the woman who persisted

You need to take a rest, and if you don’t you’re going to drown

And that’s too bad, ’cause now’s when all the real shit comes down

Banish The Shakes

Paul Ryan’s Cheat Day: Shamrock Edition

Everclear’s “Father of Mine” sputtered out of Paul Ryan’s car radio. The aux cord must not be jammed into the socket tightly enough, Paul Ryan thought. Even though he knew every word by heart, the skips distracted him. It was a perfectly good first-generation iPod, so some dirt from his pocket or his bag must’ve accumulated inside the headphone jack again. He visualized himself entering his office, bending a paperclip to clear the lint from his mp3 player, and he felt strong.

His phone chimed. Representative Kevin McCarthy bragging that he Facetimed with Trump. Trump wants to know what a health savings accounts is. Can you send him one of your Powerpoints? Do you have a Powerpoint about health savings accounts, thinking person emoji, sarcastic face emoji?

He twitched and pressed on the gas.

Why would Congressman McCarthy text him that? Didn’t he know Trump messages him daily? Didn’t he know that Trump doesn’t actually care what a health savings account is? No one fucking cares what a health savings account is. They’re a fiction, a metaphor for no socialized medicine. No shared responsibility. There’s no such thing as society. Just individuals and families.

Fuming, Paul Ryan U-turned into a McDonald’s parking lot. When he woke up that morning he wasn’t planning on it being a cheat day, he even puked in his mouth during suicides at boot camp, which usually means it will be a good day. But the iPod skipping, this text, repealing and replacing Obamacare, it was all unraveling him.

“Fuck you,” he said to himself. “It’s St. Patrick’s Day.” A Shamrock Shake could reset this day, this week, this 115th Congress.

The drive thru speaker reminded him of a confessional. Fast food orders should be confessed, he thought. There’s no reason anyone has to be obese. It’s a choice. Paul Ryan was choosing to cheat that St. Patrick’s Day, and tomorrow he’d as easily choose to not eat anything. He’d choose to call Tony Horton and choose to challenge him to a box jump contest until one of their knees blew out. And then he’d choose to open a bag of Doritos and he’d choose to breathe in so deeply that the orange residue would tingle the back of his nasal cavity. He’d choose to restrain and he’d choose to transform that restraint into power.

“Bless me, Father,” he said to the drive thru speaker, feeling like a son of a bitch.

“Excuse me,” the voice responded. A thick and deliberate Boston accent. Kennedyesque in its fakeness, Paul Ryan thought.

“Bless me, Father.” Paul Ryan doubled down. “It has been five weeks since my last confession, my last cheat.” The first travel ban, Paul Ryan thought. “I’ll have one Shamrock Shake, please.”

“Three forty nine. Please pull around,” the voice said.

Paul Ryan did as he was told. When he arrived at the window, he recognized immediately the person waiting for him.

“Senator Edward Kennedy.” He said his name like he was going door to door again, campaigning for his first race. He was so terrified that he actually sounded sincere.

“I’m the ghost of Saint Patrick’s Day Past, son. We thought, God and I, if we could somehow reach you, then you wouldn’t dismantle the healthcare law I dedicated my entire life to enacting.”

Even in death liberals still talked down to him, Paul Ryan thought. “With all due respect, Senator. You died before President Obama signed the bill.”

“And so we, God and I, beat Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher at beer pong,” Ted Kennedy’s ghost continued, “and while they were drunk and passed out, I snuck down here.”

“Ronald Reagan wouldn’t drink,” Paul Ryan simpered.

“Trust me, son. If I couldn’t get elected President, do you think the American people will let you become President after all the deaths your Obamacare replacement will cause?” Ted Kennedy manifested a political cartoon, the one of Paul Ryan’s healthcare plan pushing 24 million people off of a cliff, but the paper slipped through his fingers because he was a ghost.

“They’re preventable diseases. Obesity. Diabetes. Hypertension. They’re avoidable. Why should I pay for the treatment of illnesses people don’t have to get?

“Society is individuals and families, son,” the ghost answered.

“Will the Shamrock Shake complete your order? Anything for a work wife, perhaps? An egg McMuffin?” Ted Kennedy turned to the cash register. “My work wife was Barb Boxer. Whatever happened to her?”

“Did you know we’re not supposed to say ‘work wife’ anymore?”

“What do you call the women who accompany you when you go get coffee?”

“Colleagues.” Paul Ryan imagined Hillary Clinton and one of her aides emailing about banning the use of the term ‘work wife.’ Adding the term and its definition to the sexual harassment trainings the Department of Labor mandates. Another regulation to bog everything down. Paul Ryan gripped his steering wheel like he was about to accelerate his car into the building.

A teenager in a McDonald’s uniform walked into the booth where Ted Kennedy was sitting. “Holy shit. It’s that man who works for Trump.”

The Ghost of St. Patrick’s Day Past vanished.

“I don’t work for Mr. Trump, sir,” Paul Ryan lectured. “And thank you for coming to work today. It’s an honorable choice, full of — ”

“Not full of healthcare. At this fucking job.”

He gripped the steering wheel tighter.

“Full of quiet dignity. I flipped McDonald’s hamburgers one summer during college.” Paul Ryan stumped. This is why he entered politics. To explain how work generates your own fortune. Fortune, not privilege. He smiled as he remembered he was the Speaker of the House.

“This guy works for Trump,” the employee said to his manager.

“I work with Trump. With him.” He reached for his phone. He tapped in Trump’s private email address. The subject line read “Dismantling society.” The body read, “I have ideas about this.”

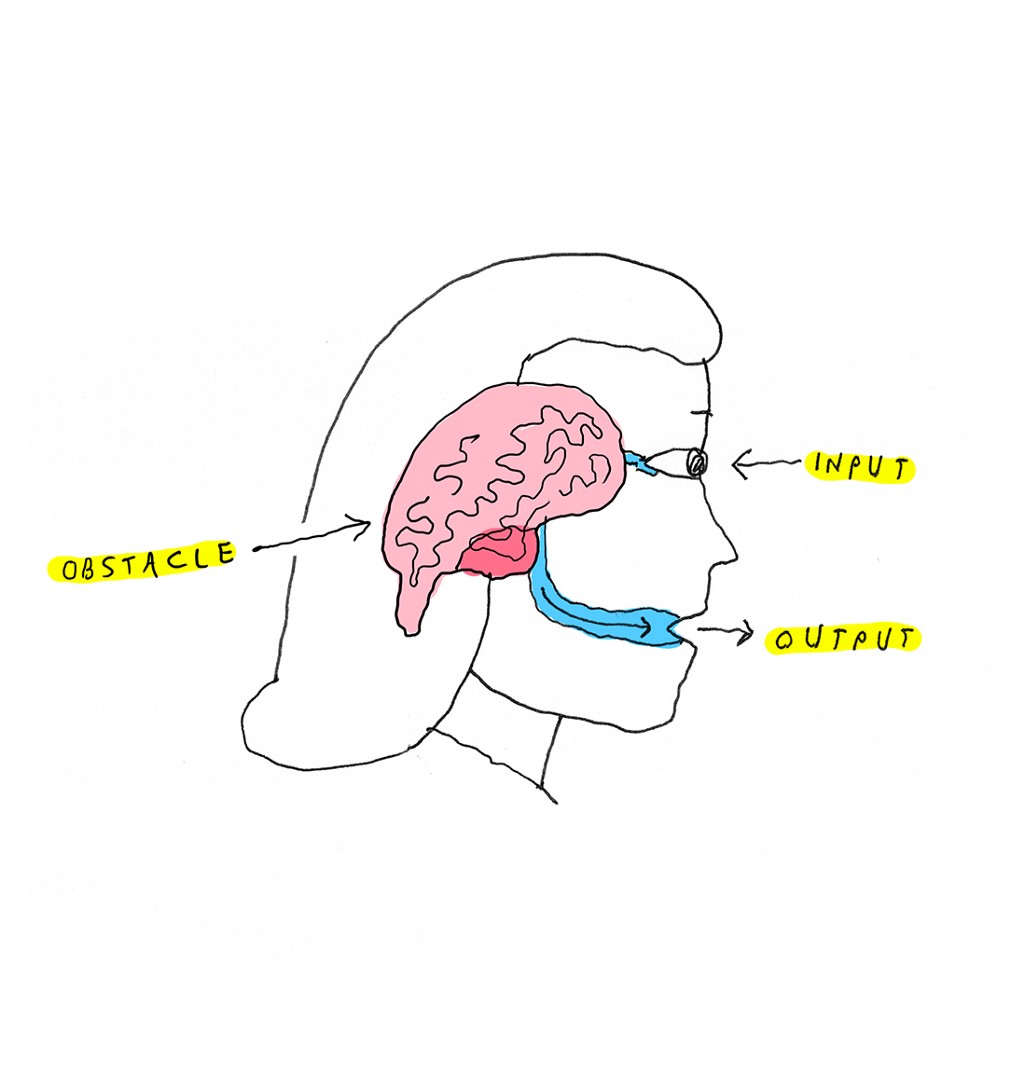

The Brain

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s work appears in The New Yorker and Catapult, and on her Instagram feed. Her first book, A Bintel Brief, was published by Ecco Press in 2014.