Gwyneth Paltrow Eats Dumb

Should intelligence determine whether animals are food?

I’ve been warning you for about a year now that octopuses are aliens, to be feared but also revered, and only eaten if you’re sure you can live with the concept of eating a very smart hand-brain. Apparently Gwyneth Paltrow has caught on to this, writing to her L.A.-based goop staff on Slack:

They have more neurons in their brains than we do. I had to stop eating them because I was so freaked out by it. They can escape from sea world and s — by unscrewing drains and going out to sea. #tangent.

They do have a lot of neurons, GP, but not more than we do. They also have three hearts and motherfucking SUCTION CUPS on their arms!!! Many widely acclaimed books have been written about these cunning cephalopods, and many of them address the idea of intelligence, consciousness, and a lot of other collegiate-sounding topics.

If you’re going to go down the intelligence road, we should probably talk about pigs. The issue of abstaining from eating animals because is so thorny, because where do you draw the line? Don’t plants have sophisticated lives too? And what about pigeons, a.k.a. squab? Food preferences aren’t really logical or even terribly defensible in a court of law. They can be moralistic, sure, but they won’t be consistent. As Natalie Angier wrote in 2009:

I stopped eating pork about eight years ago, after a scientist happened to mention that the animal whose teeth most closely resemble our own is the pig. Unable to shake the image of a perky little pig flashing me a brilliant George Clooney smile, I decided it was easier to forgo the Christmas ham. A couple of years later, I gave up on all mammalian meat, period. I still eat fish and poultry, however and pour eggnog in my coffee. My dietary decisions are arbitrary and inconsistent, and when friends ask why I’m willing to try the duck but not the lamb, I don’t have a good answer. Food choices are often like that: difficult to articulate yet strongly held. And lately, debates over food choices have flared with particular vehemence.

So don’t eat or not eat something because Gwyneth Paltrow does or doesn’t. First off, you probably can’t afford to if it’s like, magic powder that you have to add to your matcha smoothie every morning. And second, you should wade through these decisions and feelings by yourself. I have a hard time knowingly eating factory-farmed meat or dairy, but that doesn’t mean I haven’t done it. I realize that an easy way to rid myself of this anxious burden of deciding what is “okay” or “ethically consistent” to eat would be to just never mind about vertebrates entirely, or at least the mammals to start and maybe just keep the chordata because of the omega-3s, but the anxious burden is frankly the thing that makes me feel alive and human.

It is extremely amazing that humans get to sit at a restaurant and be like, “Should I eat this thing that I know is delicious, particularly when grilled to a sweet char, and which I would never make for myself at home because it’s a pain in the ass to handle and prepare plus I don’t even own a grill? Or should I abstain from eating it because I have read literally hundreds of articles about how cool these creatures are, like, is it morally inconsistent to be in awe of something and eat it anyway?” This is the privilege of being a human and I think the only way to not be a monster about it is to stay curious about your motives. At least you’ll have made a conscious choice.

And when the octopuses take over our planet (if we don’t acidify their oceans first), they will not care what you did or ate, because that sort of contemplative torture is just a made-up human thought experiment to keep society sort of always a little broken so that its constantly fixing itself. The octopuses also won’t care what you said on the internet or who the president was.

Free Shipping

Reading the Uline shipping supply catalog for pleasure

Last week a lot of creatives with Twitter accounts were pissed off at a shipping supplier. “Uline is run by garbage people,” said Oni Press’s Charlie Chu. “Friendship ended with ULINE. Now PAPERMART is best friend,” said artist Melty Buddy. “ULINE SUCKS!!!” said Bojack Horseman’s Lisa Hanawalt.

At least twice a year, Uline (a family-owned business with over 5,000 employees in three countries) sends its phone-book-sized catalog of shipping supplies to just about every business in America. That includes a lot of Etsy sellers, comic book authors, and independent artists—anyone who might need to put their work in the mail. And every Uline catalog contains a heartless political essay by company president Liz Uihlein, a major Republican donor and Trump advisor. Opinions like homeless people are scary and dumb proles shouldn’t vote. This time, she denounced health care reform, food stamps, and weed.

So if you don’t agree, don’t give Uline your money. But do read their catalog, which is otherwise a meditative pleasure.

First step, just rip out Liz’s essay. It’s painful, because once she unironically wrote “How many adults are up-to-date on the latest celebrity buzz, but have no idea what the price of a barrel of oil is?” and you’re going to miss out on that because that’s not the sort of pleasure we seek here. What we seek is nostalgia for the physical object, as practiced in classic art forms like Duchamp’s ready-mades, Kenji Kawakami’s chindogu, and Ben Katchor’s Julius Knipl.

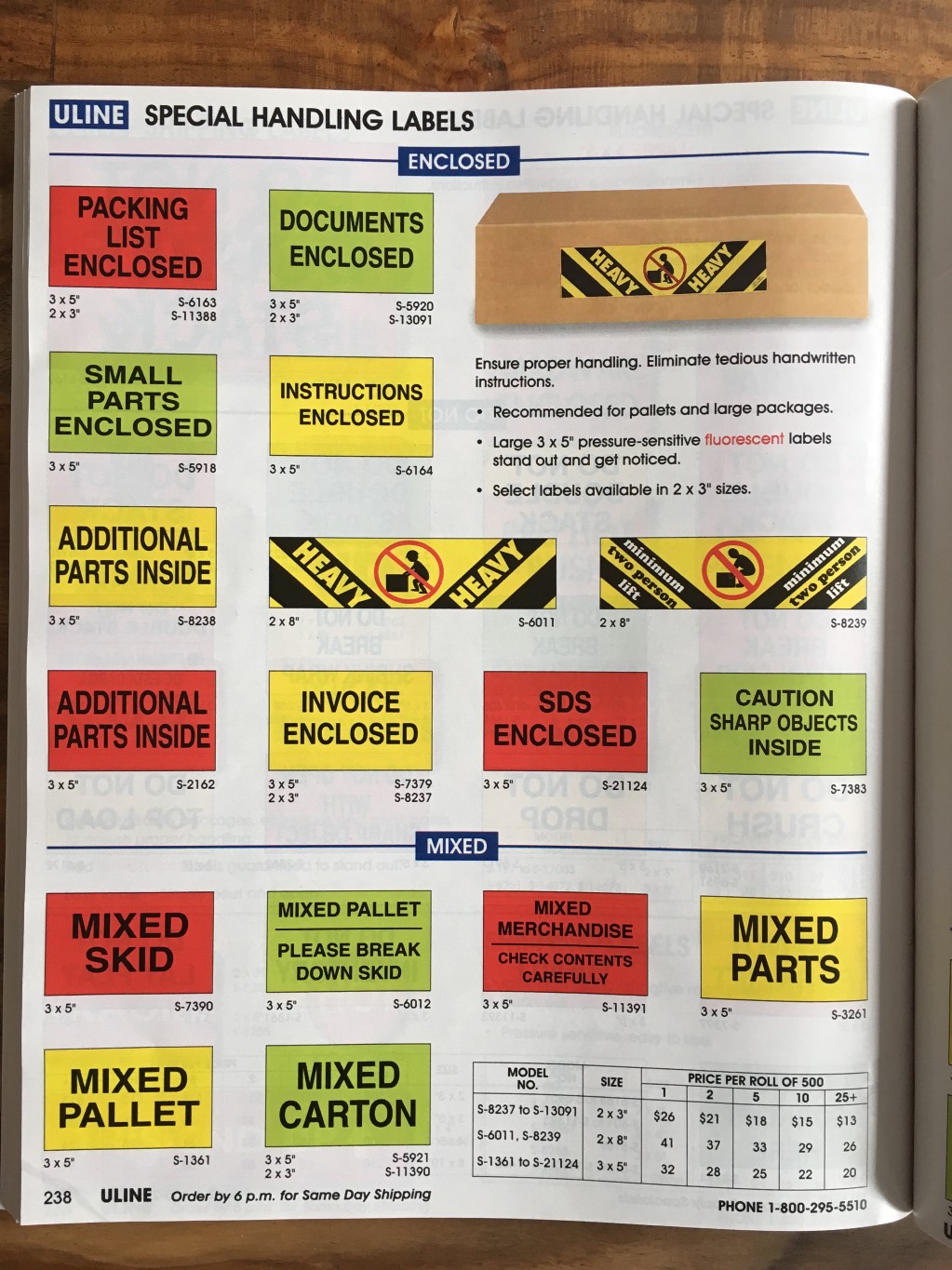

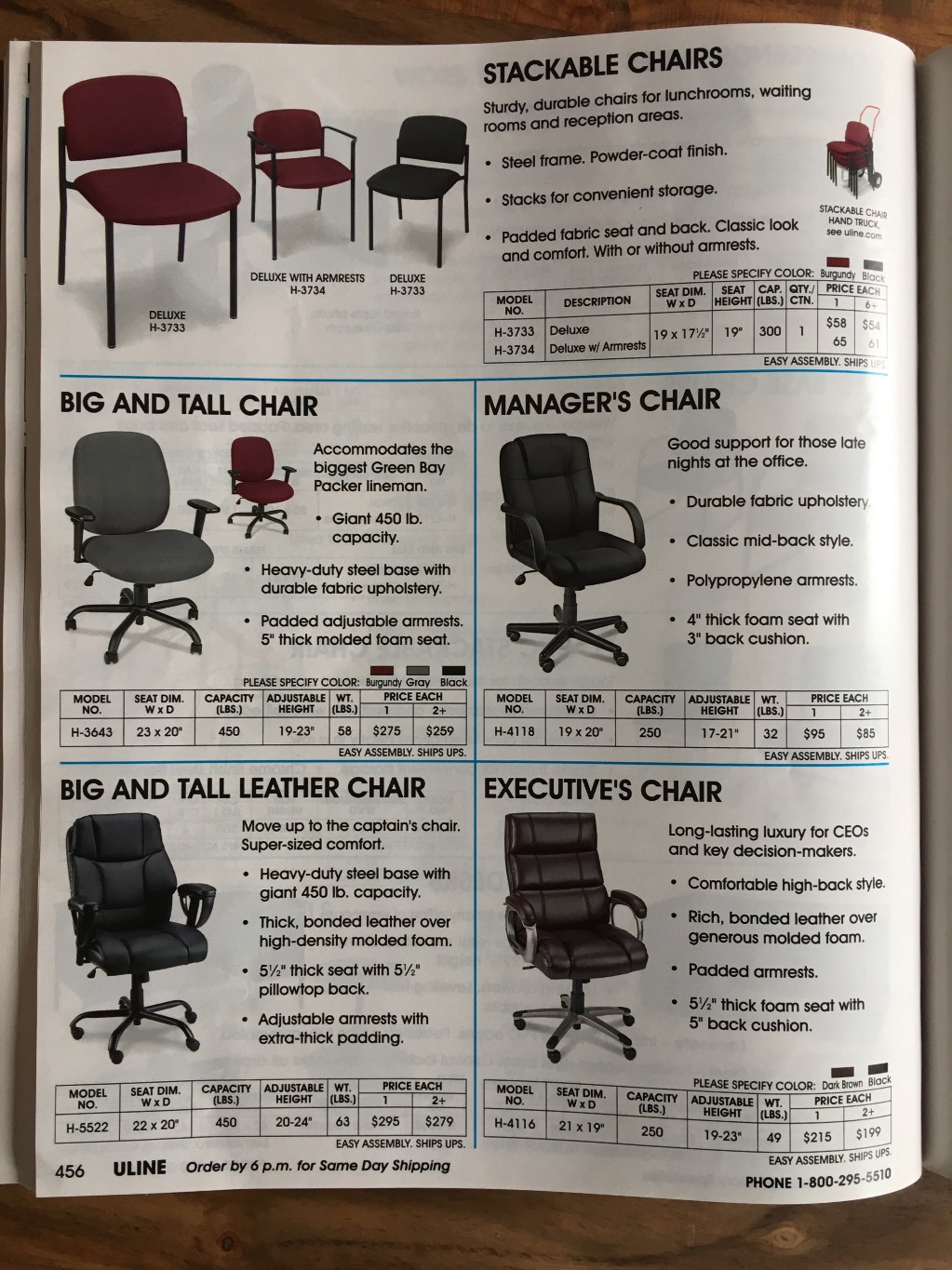

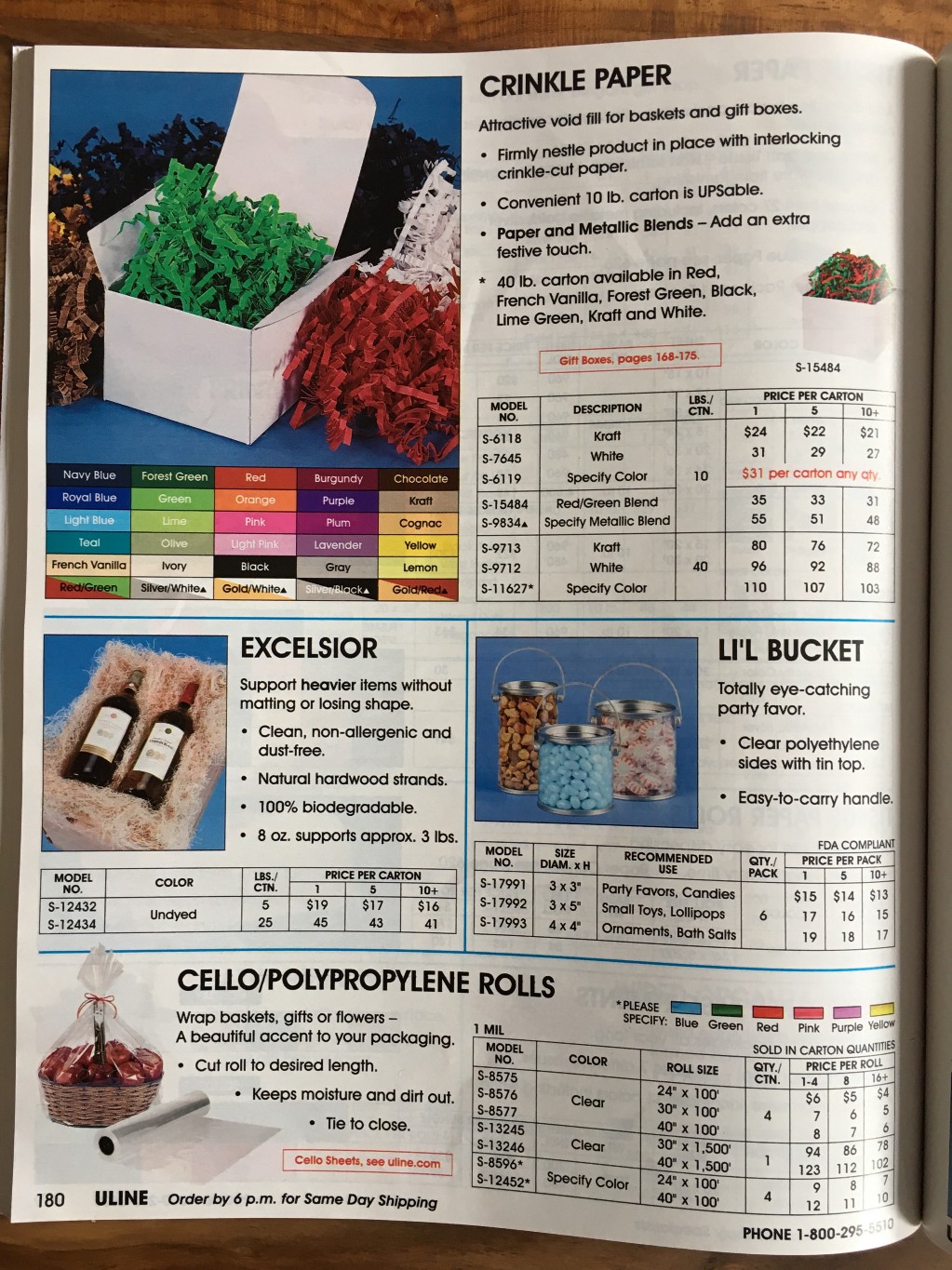

For your initial exploration, flip to any page. Pause, peruse. Flip again. On each page is something fascinatingly mundane, something you’ve only considered part of the surroundings, something other products came packaged in or trucked through or built by, now isolated and explored as a product itself, with specifications and varieties. Something like:

- Wrapping paper: Waxed, butcher, freezer, or “bogus”.

- Handicapped parking space stencils.

- Floor mats, in varieties like drainage, Superfoam, anti-fatigue, Cadillac, and Hog Heaven.

- Hair nets and beard nets.

- Staple hammers.

- The Mini Pak’r Air Cushion Machine, which inflates “25 feet of void fill per minute.” Repeat to yourself, “void fill.”

- Five-foot-high bags of industrial packing peanuts, pictured with human for scale.

- Gojo-brand foaming soaps. “Rich, creamy foam with the push of a button.”

- Those yellow bumpy rectangles on the edges of curbs.

- Strapping Protectors, which would make a great Power Rangers knockoff but are in fact the little corner pieces of fiberboard that protect box edges from the straps and ties, which would otherwise cut into them like a plastic bag handle cutting into a palm.

- Silent polypropylene: noiseless clear tape to “eliminate the warehouse racket.” Pictured with a worker taking a phone call while taping up a box.

Each listing includes a product name, a well-shot but straightforward photo, and a table of prices. There are always discounts for larger volumes. Some items are interesting in their particularity; others for the vast variety contained within a seemingly irreducible category: Reclosable bags include zipper bags, double zipper bags, slider-lock bags, drawstring bags, self-seal adhesive bags, leakproof bags, gusseted bags, in hundreds and hundreds of sizes. Very few items carry a brand name. Even cataloged and priced, they seem as anonymous and eternal as rocks.

For most of you this will be enough. For the devoted, it is appropriate to begin a cover-to-cover reading. Compare product colors and sizes: Cub Pink, Debbie Blue, Vogue Purple, Jumbo Lime. Get savvy to industry terms: carboys, frosty eurototes, heavy denier nylon. Gravity shelf bin organizers, slatwall gondola displays (“the workhorse of retail stores everywhere”). Stackable pallets, rackable pallets. The Tuscan smoker’s pole.

As a nerdchild, I hoarded brochures and bookmarks. I once received a baseball card case as a gift; I threw out the baseball cards and filled it with my collection of local business cards: contact info for roofers, accountants, and graphic designers. I developed a blank-notebook fetish that easily outpaced my writing. My favorite video game was the bookstore-simulation demo inside Excel, which came pre-loaded on a hand-me-down laptop from my aunt, along with a trial account for Compuserve. I’ve read other catalogs for pleasure, beyond the obvious clothing and furniture porn; I admired the thousand-lot plastic party favors from the Oriental Trading Company and the intricate miniatures of my sister’s American Girl catalog. But nothing speaks to infinite possibility like the shiny bubble mailers and massive wood crates of Uline. Like my notebooks and my business cards, they make me feel, without doing anything, that I can do everything.

While Uline’s catalogs are updated just twice a year, they feature sixty different covers each year. Most use the same straightforward images as the interior. Sometimes the cover features a smiling employee, a leaping carp, or a beagle popping out of a box. Occasionally the designers go high-concept with a parody of Amazon’s delivery drones, or a ring of hands in brightly colored work gloves. One cover featured two models dressed in corrugated cardboard; customers were sharing and blogging it for weeks.

Maybe like me, your life’s work lives entirely on computers. Maybe the outlets that host your work tend to shut down after a few years, leaving no concrete evidence of your years of effort. Maybe you get jealous of (and romanticize) anyone who builds something solid like a car engine or a table. Maybe you and your fellow digital knowledge workers are surrounded by fetishizations of these physical occupations, in WeWorks and coffee shops made of barn wood and Edison bulbs. You know that’s not what real work looks like. The practical world of Uline is made of plastic, styrofoam, and particle board. The models wear polos and black-soled sneakers. It’s a true representation of the physically mundane.

In the real world, all these honest objects are exploited as tools of capitalism, and the profits from selling those tools are fed into the American political machine. But the pictures in the catalog are just signifiers, as ethereal as your spreadsheets or your blog posts. If the Uline catalog can honor the material world in all its potential, then so can your work. By boycotting Uline, but still appreciating the catalog as its own end and not a means, you promote the catalog to a work of pure art, an inspirational text: Every object can be contained, every void can be filled. And your work has value, whether or not it can be counted on an easy-count digital scale.

Nick Douglas is the creator of the web series Jaywalk Cop and Nick & Siri and former editor of the blogs Urlesque and Slacktory. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and their books.

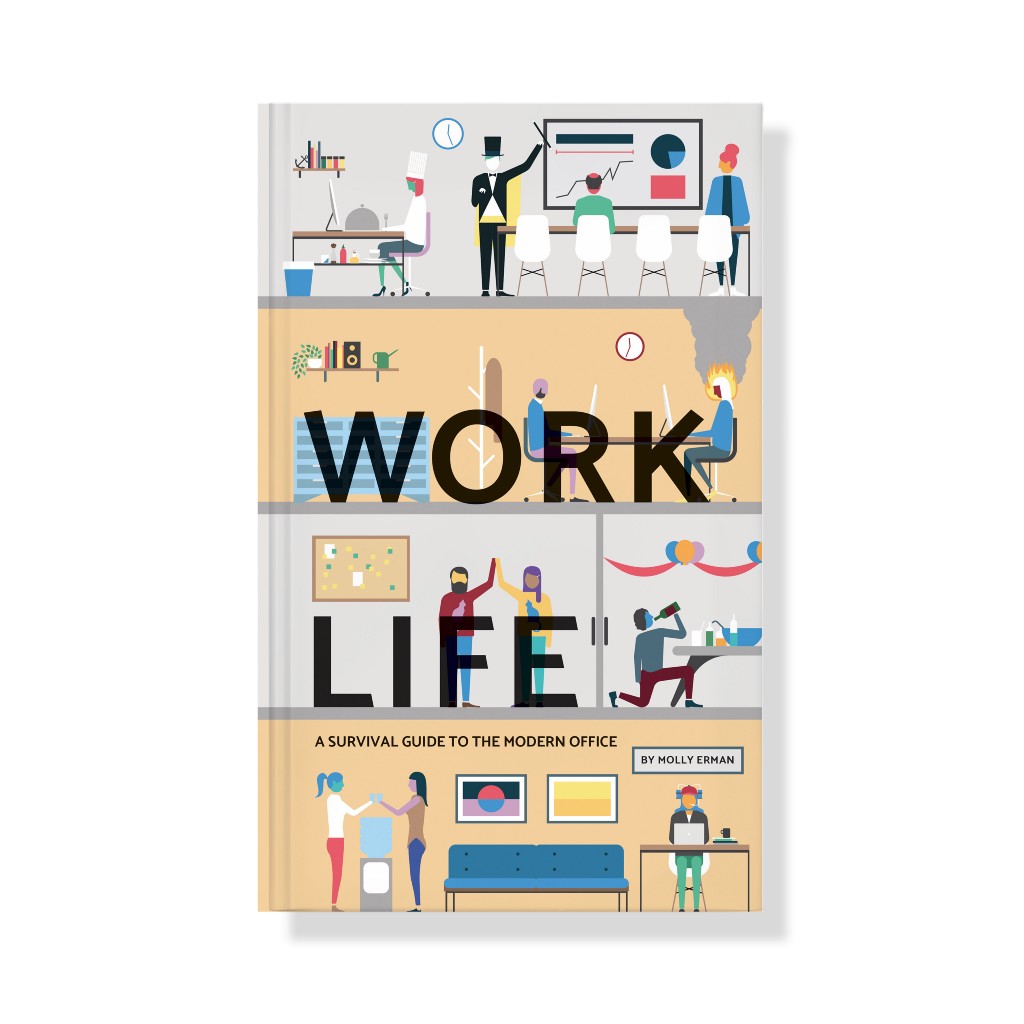

A Survival Guide To The Modern Office

An excerpt from ‘Work Life,’ out on March 21 from Dovetail Press.

I arrived in New York right after college, prepared to shed my skin. After spending over one thousand days living in Bloomington, Indiana, having listened to T-Pain’s “Buy You a Drank” so many times that it threatened to underscore all my thoughts forever, I was starting an entry-level position at Vanity Fair. (Can you hear that? It’s the sound of angels singing, remixed by T-Pain.) I was over the moon, impoverished — and, it turned out, unprepared.

I’d bought a blue Theory suit and an Ikea bed, and I was living in a windowless lime green railroad apartment with two other girls downtown. I arrived at that midtown office with earnestness and intention coursing through my body like drugs. I wanted to be wonderful. Despite my best intentions, there was so much I didn’t know about working in an office. I wasn’t alone. My roommates and I, all 22 years old, would come home so tired from workdays of trial and error that we’d fall asleep in our clothes before dinner.

I spent much of my twenties trying to understand what it meant to do “good work.” My fellow assistants and I became a mesh network of support for each other. G-chats flew between us in real-time as we contemplated pressing questions — how to request time off, how to deal with a disrespectful coworker, and what to do if you’ve seriously effed up bigtime. Is office dating always illegal, or is it kind of okay? Can you leave the office before your boss, or should you stick around — and what to do if it’s 9 P.M.?

Somewhere along the way (before the proliferation of the word “adulting”) we figured it out. We got bigger jobs, and stopped sending each other “SOS” group texts. Last year, when I was trying to wrap my head around having lived in New York for a decade, I decided to write the work handbook that my friends and I could’ve used during that hot confusing summer that we all landed here. Work Life: A Survival Guide to the Modern Office is a recreation of the friendly, whispered wisdom I benefited from in quiet corners and on walks to grab coffee. (Make that coffees. I still have the orders memorized.)

My grandfather always said the key to success is to “Walk in like you own the place.” My hope is that Work Life makes that easier to do.

It’s okay to get angry, just don’t press “Send.”

Ditching the plastic utensils restores self-respect.

Embrace your mistakes, then keep it moving.

Admittedly, this is my favorite illustration in the book. Courtesy of Dovetail Press.

Sometimes you’re sick, and sometimes you need to seem sick.

Molly Erman is the author of “Work Life” and the Director of Communications for New Lab in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. She is an alumna of The New Yorker, Alfred A. Knopf, Artisan Books, and Vanity Fair. Molly lives in Manhattan, where she strives to keep her houseplants alive.

No Platform

What do the rapacious monsters who are ruining everything want?

If you have had a hard time articulating to yourself or others why the “new economy” for which a large sector of our technology and business media continues to cheerlead is actually a scam of epic proportions that will fundamentally destroy whatever is left of this country’s tattered social contract, here is one sentence that will help you on your journey to expression:

“Platforms seek total control even as they abdicate responsibility.”

It comes from this piece by John Herrman, the rest of which will enable further understanding. Everything is terrible, but at least you can have a better sense of why.

Platform Companies Are Becoming More Powerful – but What Exactly Do They Want?

Brothers Black, "Analog Relief"

Remember when people weren’t always asking if you remembered when everything wasn’t always crazy?

Good morning. This track is called “Analog Relief” and it is, I fear, the only sort of relief you will receive for some time. I therefore strongly urge you to enjoy it, because I know what the rest of your day — week, month, etc. — will be like and, well, see the previous sentence. Okay, let’s do this. Enjoy.

New York City, March 19, 2017

★★★★ The banks of ice were still standing. They were begrimed by now, especially on their street sides; even so, the ambient filth of days had not saturated their hard surfaces the way it would have soaked into soft snow. A dump truck went by with dirty chunks of hardened snow sticking up out of its bed. Pigeons crowded around dark yellowish and glistening chunks of food on the still-white ground inside the little fence of Sherman Square. The midday shade was a little bit too chilly after walking in the sun, but by afternoon the warmth would spread. Dirty water sparkled on its way into the storm sewer.

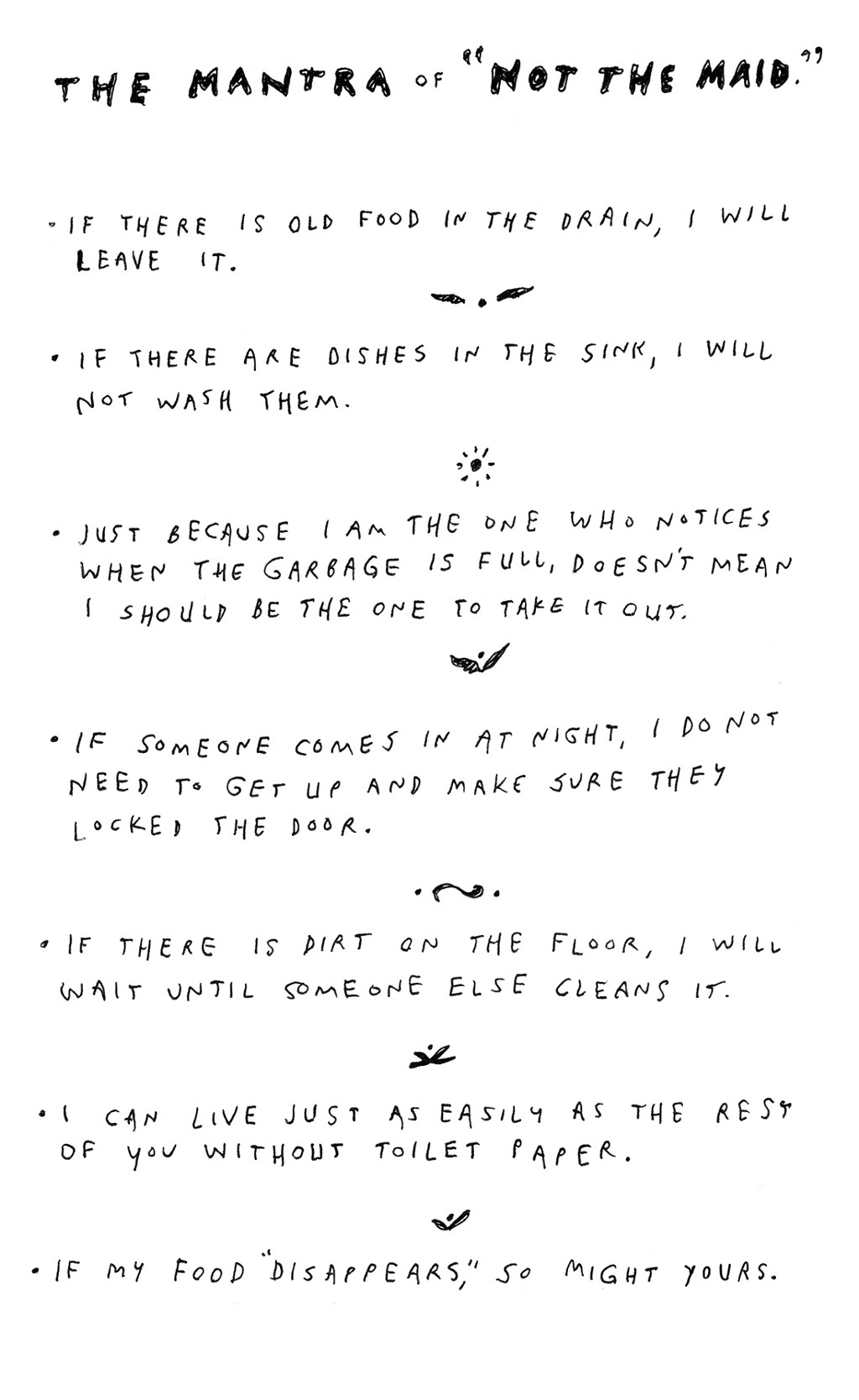

Not The Maid

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s work appears in The New Yorker and Catapult, and on her Instagram feed.

Campus Ambivalence

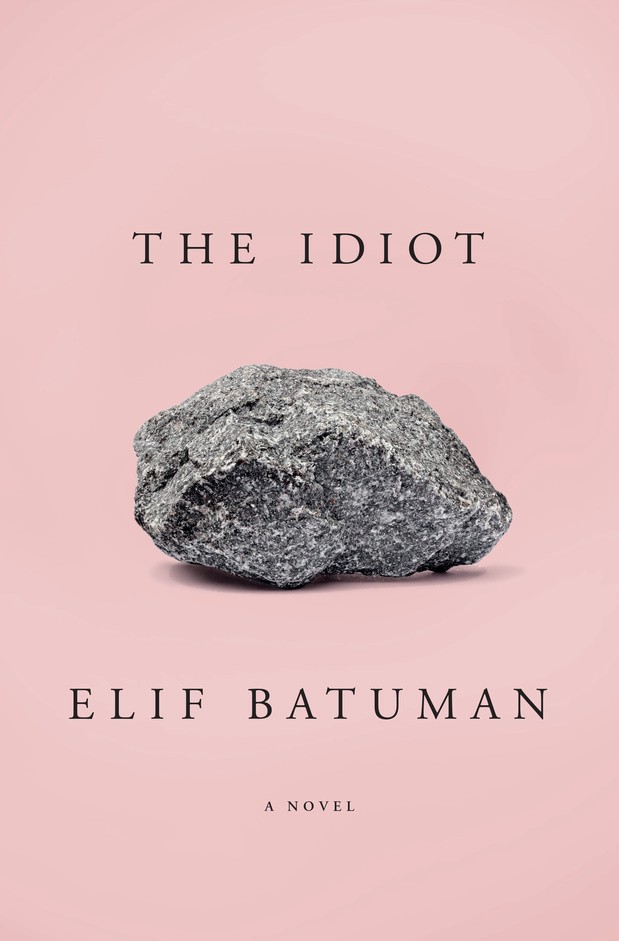

The Aimless College Romance Set In The Aimless Romance of College

Elif Batuman’s ‘The Idiot’ is a satire of the campus novel

Most people come to college uncertain what to expect. I arrived on campus armed only with information gleaned from seasons 4 and 5 of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and a distinct awareness that over the next four years I was supposed to and indeed expected to “find myself.” Selin Karadağ, the protagonist of Elif Batuman’s The Idiot, isn’t sure what to do as a freshman at Harvard in the mid-1990s; she seems genuinely to be there to study, and is diligent if not purposeful about it. She ends up accidentally checking every box of the stereotypical college experience anyway: learning a new language, volunteering, studying abroad, getting drunk for the first time, and falling in love.

The plot is minimal: Selin enrolls in linguistics and Russian classes, and begins talking to Ivan, a Hungarian senior in her Russian class. Their correspondence turns into an epistolary romance that’s painful, occasionally thrilling, and mostly disappointing. At the end of the school year, Selin enrolls in a summer program to teach English in Hungarian villages and has a summer that feels “like reading War and Peace: new characters came up every five minutes, with their unusual names and distinctive locutions, and you had to pay attention to them for a time, even though you might never see them again for the whole rest of the book.”

All of her experiences turn out to be less exciting, less enriching than they are supposed to be, if they don’t backfire completely. The Idiot is a parodic subversion of the college coming-of-age story — the classic narrative of the college experience of an upper-middle-class young person attending a liberal arts or Ivy League school, usually written by an upper-middle-class graduate with some adult perspective. But in this depiction, no hindsight intrudes, and it’s very much not idealized; Selin’s experience comes across as largely cringeworthy, boring, and nonsensical, just like college really was.

Selin slogs her way through classes that attempt to instill a comically exaggerated (but painfully accurate) version of abstruse academic thought:

You wanted to know why Anna [Karenina] had to die, and instead they told you that nineteenth-century Russians were conflicted about whether they were really a part of Europe. The implication was that it was somehow naïve to want to talk about anything interesting, or to think that you would ever know anything important.

She sets out on a path to become a linguistics major, thinking that way lies the key to understanding language, but little does she know her Linguistics 101 class will turn out to be the most arbitrary and dogmatic of all. “I don’t know what anything means,” she complains to Ivan in an email. “I have this book that says LANGUAGE on the cover and isn’t teaching me anything.”

Selin hasn’t yet read Barthes, but she seems to intuitively grasp that, as A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments tells us, romance is a lot like close reading. And just as her literature professor ignores the question of what the text means, Ivan’s motives remain frustratingly opaque to Selin. Ivan shows Selin some pictures from his vacation, including pictures of his girlfriend (of course he has a girlfriend). “I looked at the picture carefully, trying to figure out what made her a girlfriend…There was a donkey in the picture. That couldn’t be relevant. Or could it?” Everything has meaning in the text that is the beloved; the lover is inevitably driven by obsession to become a literary critic, analyzing everything the beloved says or does to death.

Ambiguity in love mirrors Selin’s academic exasperation with the idea that things simply don’t mean anything. Our budding linguist says, “Insignificant subtleties are the only difference between something special, and a huge pile of garbage floating through space. I’m not making that up. People discovered it in the nineteenth century.” She’s impatient with the idea that words can mean whatever you want them to mean — an idea that’s been in vogue among academics since the sixties or so, and may or may not have always been a tool of trash men, hell-bent on wasting women’s time since the beginning of human history. No one can catch you being dishonest if you have plausible deniability about what you meant.

The pursuit of insignificant subtleties leads Selin to read a lot into Ivan’s words, but sometimes she would have been better off taking them at face value. While on a “date” that is of course not actually labeled a date, she learns firsthand about Ivan’s slippery rhetoric:

Periodically Ivan would say I should talk more and keep him from bullshitting. It wasn’t clear to me in what sense he meant ‘bullshit.’ I had the uneasy feeling I was being warned about something. I said no, it was interesting. He said he just didn’t want to feel that he was telling me all this bullshit.

Note that she doesn’t say: “He just didn’t want me to feel that he was telling me all this bullshit,” or “He just didn’t want to tell me all this bullshit.” Ivan doesn’t mind acting out a questionable scenario; he just doesn’t want to feel uncomfortable about it.

The questionable scenario, of course, is that classic college freshman-girl milestone: becoming romantically and/or sexually involved with an older guy, particularly a senior. (See “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” season 4, in which freshman Buffy, ever the overachiever, dates a grad student who is also her TA). It’s no coincidence that these types of relationships are so common. It is important to remember — as Ayesha Siddiqi notes in a piece I re-read regularly — “attractiveness is codified along a gendered division of power.” To be a feminine, conventionally attractive woman is to be or appear to be young, innocent, frail, vulnerable. These same hegemonic standards expect men to be tall, strong, socially and physically powerful. Freshman girls arrive on campus as “fresh meat”: cuter, more susceptible to flattery, and more eager to please than their older and wiser female peers. To them, senior boys may seem intriguing and mature, whereas senior girls see these 22-year-old dweebs for who they really are.

Older men are known to use explanation and interpretation to reinforce their structural advantage over younger women. Selin writes to Ivan about Pablo Neruda’s “Ode to the Atom,” an allegorical poem in which an atom is seduced by a general, creating nuclear weapons. Ivan writes back in a pensive tone, twisting the allegory in another direction entirely:

Your atom, I think it will never go back to peace…Once it has been seduced there is no way back, the way is always ahead, and it is so much harder after the passage from innocence. But it does not work to pretend to be innocent anymore. That seduced atom has energies that seduce people, and these rarely get lost.

Not only has Ivan found a way to sexualize an atom, he’s implicitly gendering it, too. What gender do you think an entity that is seduced, thereby losing its innocence, and then becomes responsible for allegedly seducing people — not through its actions, just through its “energy” — could possibly be?

It’s possible that Ivan’s feelings about Selin are a little more complex than the projected narrative about the atom (spoiler: no sexual activity ever occurs between them, though it’s unclear whether Ivan’s as ambivalent about that as Selin is). In one scene, when Selin and Ivan are in a bar and “Linger” by the Cranberries comes, the song feels “ominous” to her because of “the aestheticized girliness, infatuation, and weakness” of the singer’s voice. Selin tells Ivan she doesn’t like the song…and Ivan replies that he does. This would be an innocuous disagreement — the Cranberries are an acquired taste — if it weren’t representative of a lurking power disparity between them.

Selin occasionally withholds or cuts off communication to gain the upper hand, to “win” some contest of power, but that doesn’t change the fact that Ivan has control of the relationship. He dictates its terms. At first he wants to keep their relationship strictly to email, “because spoken language is so demystified, so simplistic, a trap” (no, really), so that’s what they do until he decides they’re going to hang out in person. Their relationship might be based on some mutual feeling, but it’s fundamentally unequal. After Ivan takes Selin to a bar for a beer even though she’s underage and doesn’t feel like it, she recalls,

I felt so unhappy. I just didn’t understand why we couldn’t skip the part where I drank two more pints of beer. ‘Well, I wouldn’t want to push you,’ Ivan said, somehow ironically, as if alluding to the scenario known to both of us in which boys pushed girls, and which was so obviously not what was going on.

Ivan’s motivations don’t seem all that sinister, just inconsiderate and dickish. It’s so textbook it seems inconceivable that Selin doesn’t realize he’s no good. But who hasn’t fallen for the exact equivalent of this person — tall, intelligent, mysterious, sure of himself, and so clearly not respectful of your feelings? After all, the effect of someone’s charm is hard to rationalize away while you’re experiencing it. It is only on the second read, with more distance, that the horrible things Ivan says really stand out. He tells Selin he sympathizes with Raskolnikov’s decision to murder an old lady in Crime and Punishment because it was the only way to study in peace (Selin’s reaction: “I wondered why he had told me something so terrible about himself”).

Selin’s remark mid-book that Ivan “felt to me increasingly like the parody of a love interest” is the most obvious indication yet that the romance she’s embroiled in is a Mad Libs version of a college romance. Ivan also hangs a subtle lantern on the stereotypical scenario he and Selin are acting out: “Apparently now I have to show off to you my record player,” he quips after bringing Selin back to his dorm room. Lakshmi, a cool and beautiful fellow freshman Selin comes to know through the student literary magazine, describes her relationship with a senior boy, Noor, that is clearly just a more glamorous-seeming version of Selin’s frustrating, confusing, unsatisfying, physically unfulfilled relationship with Ivan. Noor is also intriguingly foreign—a literature major from Trinidad who moonlights as a DJ—and together he and Lakshmi do ecstasy and talk about post-colonialism. It all sounds much cooler, but Selin and Lakshmi feel similarly disappointed, vulnerable, embarrassed, and jerked around by their respective non-relationship relationships.

Being involved with terrible men is supposed to be a rite of passage for young women—a sad bit of conventional so-called wisdom that in some ways echoes “boys will be boys.” But in The Idiot, there’s clearly not even much to learn from this aimless romance. At the end of the novel, Selin concludes, “I hadn’t learned anything at all,” specifically within the linguistics department but presumably in a broader sense. But there does seem to be a moral or lesson, or at least a phrase that pops up midway through the novel and becomes a sort of motto: “What is man that thou art mindful of him.” And isn’t that the most important thing young women living in a patriarchal society need to learn, after all? That man doesn’t warrant quite so much effort and attention? “What was man? It occurred to me that I could be less mindful of man, and I seemed to catch a glimpse of freedom,” Selin says to herself in order to remain in emotional control when she gets a phone call from Ivan.

While Selin’s not emotionless, she is logical; that serves as her best defense against the cultural imperative that women subordinate their own desires to those of men. When she hears a song consisting of the line “I miss you, like the deserts miss the rain,” over and over again, Selin wonders: “Why would a desert miss rain? Why wasn’t it okay for a desert to be a desert, why couldn’t anything just be what it was, why did it always have to be missing something?” Why, in other words, does a fish need a bicycle? What is man that thou art mindful of him?

The bright spot throughout all of Selin’s tribulations is the wit and intellect with which she recounts them. She may not feel like she’s learned anything from her freshman year, but the reader knows about her what we all wish we could tell our younger selves: don’t sell yourself short; you’re more wonderful than you realize, and the whole messy question of other people will sort itself out. Maybe.

What's The Best Place To Be On The Subway?

I’ll Give You My Subway Seat If You Promise Not To Urinate on Me

And other answers to questions you didn’t ask.

“What’s the best place to be on the subway? I used to think it was leaning against the doors. But now I am not so sure.” — Subway Stan

This depends on what subway system you are on. The Green Line T in Boston has these bendy parts in the middle of every trolley that are great to stand in. But none of the other lines are at all bendy. In Washington D.C., you have to get away from those doors, man. They will close right on your face and drag you for miles by the face. Not a fun ride.

My two favorite rides is a tie between the Roosevelt Island Tram in New York and the Duquesne Incline in Pittsburgh. Neither one of them goes anywhere in particular. But the view of New York is pretty amazing from the Tramway. It is like you are floating away past the bridge. The Incline is a house that goes up a hill. That is pretty awesome. I have always wanted to live on a house on a bridge, like the one in “It’s a Wonderful Life.” But a house that goes up a hill is even better. You get a nice view of Pittsburgh from the top of the hill. Pittsburgh has lots of bridges. And they put French fries inside of sandwiches for some reason.

Most of the time, I’m not riding the subway for fun. I’m riding it because I have to go someplace. Like the dentist. Or court. So I’m really in it for speed and ease. And not for thinking lyrically about traversing the clouds. I used to be big about leaning against the doors. I used to think the doors were the only place to be. I don’t sit on the New York subway unless it is absolutely necessary. Like I’ve had a rough day in the dentist’s chair. There is just too much of an emotional battle for every seat, I can’t be a part of it. So much attention is paid to where are there seats, how can one get a seat, who should be sitting, manspreading, etc. The seats are basically like the Korean border. And I just can’t participate in that kind of tense warfare.

I will sit on the PATH trains that zip me to and from the city. They have this one-person seat that is sometimes right near where the conductor works the knobs and buttons and looks out the window to make sure no one’s face is stuck in one of the doors. So you have one seat to yourself. You can watch the conductor fiddle with the instruments. And you don’t have to worry about anything. Except falling asleep and waking up in Newark.

I usually get stuck in the middle between the two doors holding onto the ceiling for dear life. The ceiling I don’t mind touching. The bars I don’t mind touching. Everything else on subway trains I imagine has been recently urinated on. Everything in New York that’s shorter than 6 feet tall has been recently urinated on, according to my calculations. That’s not necessarily always bad. Urine isn’t sterile, but it’s not as bad for you as bed bugs or the clap or whatever else is on those seats. Why do people scramble and battle for those seats?

On the PATH train, the best place other than the aforementioned one-person seat is the one in the middle of the train car in front of the TVs. We have our very own train TVs, bitches. It is an informative version of NBC 4’s news cast. Except with no sound. Plant yourself right in front of the TVs. They have fun games like Scramble and Guess Who’s From New Jersey. Michelle Rodriguez of The Fast and Furious movies is. The Scramble is way too hard; they always put the first two letters so far away. There is also a guy that reviews new movies. He always seems to give them a silent thumbs up.

If you’re in the middle of the car, away from the doors, with a little hold on one of the bars, you’re OK on the PATH train. On the New York subway, I think the best place to be is the same place. Although there are no TVs. People would probably urinate on them. They tried to put TVs in the Boston T stations but Bostonians were pretty sure they were some kind of hideous thought-control experiments. I could get with thought control experiments if it would make people not urinate all over everything. Or to stop Showtime.

Is there any more dreaded word that could tickle the Subway riders’ ears? I always seem to forget my headphones on days when I have to go to Brooklyn for a poetry reading and then it will be Showtime, right on the bridge. If I’m in the middle, without TVs, I will probably get kicked in the face. These dudes have mad skills, don’t get me wrong. And usually they will not kick you in the face because they are so talented. But the feeling that you’re going to be kicked in the face is almost as bad as being kicked in the face.

Being in front of the doors is just too much. You have to get out of people’s way and still preserve your place leaning in front of the doors. You don’t want to be more than arm’s length from the doors. Then you’re nowhere. You’re being hit by people’s backpacks. You’ve got arms in your face. People want to get by you, even when the train is moving. You are rolling around the subway car like a discarded Mountain Dew bottle. Just rolling and rolling, belonging to nothing and no one. Alone and afraid and possibly the next thing to be peed on.

There is no 100% foolproof place to set up shop on public transit. There are just too many variables. You’ll get a seat and then you’ll feel bad for some lady and you’ll have to give it to her. You will be leaning against the doors and then the doors will open and you will fall out and have to live with the Morlocks who live in the subway tunnels. Never ever pull the emergency brake unless you want to create an emergency. And always remember, sometimes after a long day, there are worse things to sit in then dried urine.

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works at a bookstore.

Winter to Spring

The changing of the seasons, illustrated

The crows make cut-paper silhouettes in the snow.

Winter stalled. We kept undercover. We didn’t believe the news. The trees threw sticks while the kids built schools of blocks and taught plastic smiley faces to read. The sky was the color of paper.

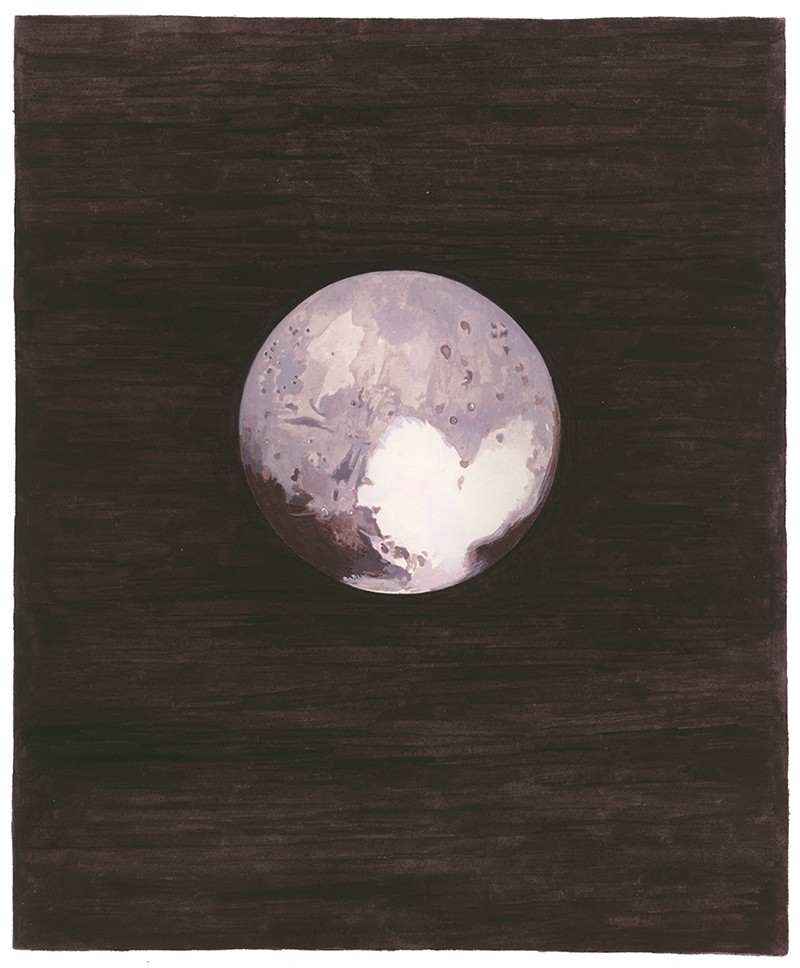

At the edge of the solar system Pluto sends a cold-hearted Valentine.

The storm came and set up a thick crust of snow no good for forts or footprints. The shrews and mice tunneled beneath and occasionally ran across the road. I saw one in the evening and thought it was a dry leaf until the car lights picked up the shine in its eyes. Midwinter dirt and frost stuck to boots and coats, socks and gloves, hats and hands.

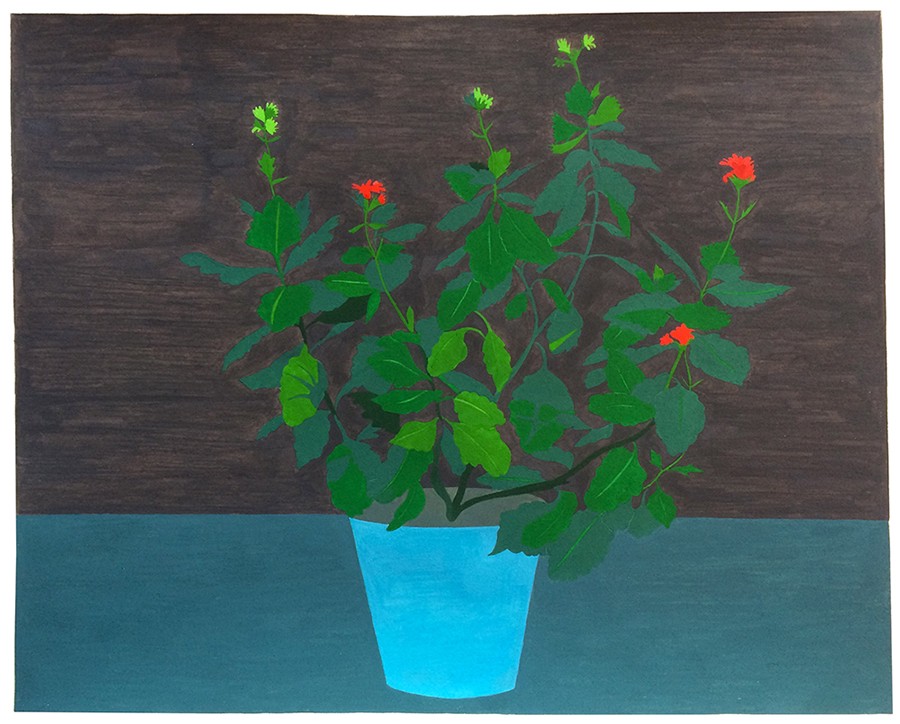

The houseplant delivers small bouquets of red.

Moment by moment the light returns. Underground the roots are waking up and neighbors tap the maples for sap. Gallons of sap boil down to a few cups of syrup. It is a long process. There will be a slow burst of new color soon. The trees offer bits of crimson out the tips of their branches. The houseplant extends its red messengers.

The daffodils turn their star faces up to the sky.

Yellow arrives first in small bundles — the crocuses then the daffodils rise up to open bright blooms. Graylight shifts to yellow, to green, to pink. On this we can count. Spring is in the air.

Spring Is In The Air!

(Previously: Fall to Winter)

Amy Jean Porter is an artist who lives in Connecticut.