Stop Renaming Neighborhoods

“The real action, though, was on the side streets, populated by the myriad businesses needed to produce a garment, making everything from fabric to pins and needles. There machines and people worked day and night filling the orders left by buyers from across the country. I remember pushing my way through the hundreds of master cutters and patternmakers who crowded the sidewalk along 38th Street at lunchtime, dodging the hand trucks carrying stylish garments that later appeared on the backs of women from east coast to west. This is what the words ‘garment district’ meant. Every one recognized the garment district not just as a geographic designation, but also as a living entity.”

— Jewelry historian Jean Appleton argues against a business association proposal to change the name of Manhattan’s Garment District to the “Fashion District.” Doing so, she said, would “erase a vital part of New York’s past.” I still can’t over how anyone thought it could be a good idea to change the name of neighboring Hell’s Kitchen to “Clinton.” Hell’s Kitchen is the greatest neighborhood name in the history of the planet.

Becoming Stephen King

Becoming Stephen King

by Michelle Dean

“Critics are men who watch a battle from a high place then come down and shoot the survivors,” Ernest Hemingway once wrote, with typical pugnacity. But are the critics sometimes right? In this occasional series we’ll examine the early careers of now-beloved authors to see what the critics first made of them.

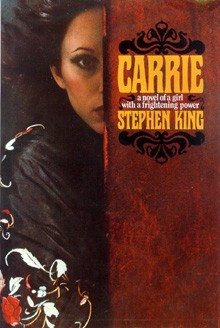

Carrie, the high-school revenge fantasy that launched a thousand tampons, started out in Stephen King’s mind as a short story. He intended to place it, according to his memoir On Writing, with the magazine Cavalier. (Cavalier was a Playboy/GQ precursor that is still published today in a slightly less exalted form.) He’d been writing a lot for them; it was the chief way the Maine schoolteacher could make any money. His salary was just $6,400 a year, a little under $30,000 in today’s terms. Cavalier’s intermittent checks had bought the family things like amoxicillin for his young daughter’s ear infections.

Blessings like those had convinced King that the only thing worth writing, at the moment, was short stories. They paid. So when Carrie began to flourish, extending long past Cavalier’s 3000-word limit, he threw it away. The length wasn’t the only thing about it that troubled him; he also felt he didn’t know enough about girls to write it. His wife Tabitha pulled it from the trash, and insisted he continue it. She promised to fill him in on the ways of young women. And within three months he had a seventy-thousand-word novel.

Doubleday bought it for $2,500, the equivalent of just under $14,000 today. People in the publishing world loved the novel, and by the time Doubleday was looking to sell paperback rights the price was at $400,000, of which $200,000 went directly into the pockets of the agent-less Mr. King. For those keeping track, that means King cleared what is about a million today on the paperback of his very first novel.

When the novel was published in hardcover in 1974, it wasn’t reviewed by any of the major publications, though it got a tiny plaudit in the New York Times from someone writing the mystery column, one with the engaging title of “Newgate Callendar,” who observed, “That this is a first novel is amazing. King writes with the kind of surety only associated with veteran writers.” “Hard to believe,” sniffed a less-impressed reviewer at the Chicago Tribune, “but almost as hard to put down.”

But for all the money and relatively good reviews, Carrie sold only 13,000 copies in hardcover, which back then wasn’t impressive enough to put it on the New York Times bestseller list. It took Brian De Palma buying the rights, and the release of the paperback in 1975, for it to sell a million copies. It was only then that the Stephen King that you and I know, and grew up with, was on his way.

It just goes to show you: it’s not just luck you need to have a successful literary career. It’s luck, piled on luck, piled on luck again, and around the corner, you need another sprinkling of it. That’s just the way the Fates roll.

There are, of course, those who wish that Jesus had taken the wheel from the Fates when they anointed King the Biggest Thing in Books People Actually Read For the Last Thirty Years Or So. Recently, apropos of very little, the LA Review of Books published an essay by someone named Dwight Allen entitled “My Stephen King Problem.” I’d summarize it for you but I doubt I need to. King is the kind of writer about whom everyone has some grand sweeping opinion, and the negative ones are all the same: He’s a hack, here is a terrible sentence, there is a cliché, a stock character. The peons all read the man and they do not want from literature what I want from literature, which is enrichment and philosophy and definitely more than a few references you’d have to pay college tuition to understand. You know the routine, everyone’s danced it a few times.

We have this argument about a lot of writers. Particularly the rich ones. Particularly the ones who get rich off the first novel. And much of the time those authors’ egos are so inflated that they deserve it. Thinking of yourself as the Second Coming of Literature is an unflattering figure to cut, and a lot of people mistake money — or its fickle brother-in-law, media attention — for real, heartfelt praise. People like Vidal, and Mailer, and, well, Bret Easton Ellis: chest-beating appears to be the way they ward off the inevitability of Death. (At least two of them have been proved wrong.)

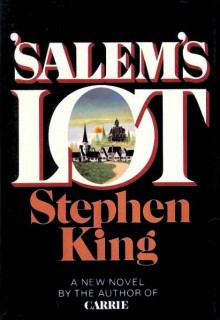

But then King was never like that. When Salem’s Lot, his second novel, was published, bestseller status was a preordained thing. The reviews were sparse, but slightly more sanguine this time — a Chicago Tribune writer complained the book was “a bit long,” presaging the self-diagnosis of “diarrhea of the typewriter” King would offer in later years. But in September 1976, it would hit the number-one spot on the paperback list. And to celebrate the occasion, King wrote something for the New York Times Book Review. He wrote an essay about someone else’s novel.

The novel in question — David Madden’s Bijou — was a smaller, more literary release. It was a bildungsroman about a young man who worked as an usher in a movie theater. King said it was “one of the books I admire most in the world.” He compared it to his own book, finding Salem’s Lot too easy, too accessible: “Bijou is a cooler ocean, and the footing underneath shelves off much more suddenly.” And, King noted, it had taken Madden six years to write it. In exchange for that sweat of brow, Madden had earned a $15,000 advance, about $2,500 a year. In exchange for the eight months King spent writing Salem’s Lot, he stood to make about half a million.

From there King’s piece devolves into a half-hearted defense of his style, which he refers to as the “Plain Style,” rounding up Robertson Davies, Milton, Joyce Carol Oates in an unlikely army for the defense of “honest books.” Like so much of King this argument is a bit rambly, a bit kitchen-sink, if pleasantly so. And at the end all he offers to the aspiring writer is the potential to do your honest best:

The object in view is to not let the money sway you from that, or the critics, or the wrath of god. Honest intent has nothing to do with art, one way or the other; art is its own master and talent is merely its whore.

His upshot is that the only thing you can do honestly is “sit down in front of the typewriter and do the best job you can.” That is the kind of plainspoken advice that can both comfort and drive critics crazy. Because there are a lot of people out there earnestly writing their opuses on nights and weekends, in the margins of bad jobs and marriages. But the doggedness isn’t enough to rescue the work.

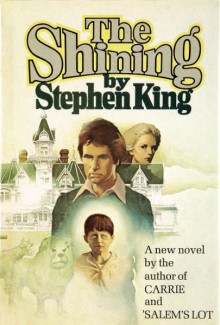

That theme — that it isn’t enough to be honest — played out when The Shining, published in 1977, finally put King in the sightlines of the literary critics. King has often said that the book is somewhat autobiographical, at least as regarded his less-than-ideal (not to mention alcoholic) state of mind, though he said he didn’t quite know it as he was writing.

In any event, critics did not feel he had done the best job he could. Richard Lingeman, in the Times, deemed King “a writer of fairly engaging and preposterous claptrap,” whose chief talents were his imagination and his ability to gauge the market for his sort of work, chiefly the young and impliedly credulous. Another reviewer, Jack Sullivan, found the clichés too much to bear, and hated the way King had of apologizing for them right in the text. (In King’s defense: Getting to use this tactic is one benefit of making your protagonist a writer, like Jack Torrance is, one supposes.) The scares the book offered were not enough for Sullivan; though he did find a few scary, “the hyperbole and stylistic fumblings make an equal number unintentionally funny.”

A freelance reviewer for the Chicago Tribune was something of an exception. He liked The Shining well enough, though he spent over half his review in an abstract riff on the frightening ways of children, which suggests he may have missed the boat on The Shining’s actual villain. But he also took the opportunity to backswipe at King’s prior achievements: “Carrie is badly written… for all its far-out scenes [it] is merely appalling and somewhat numbing in effect.”

I happen to disagree with this critic, but I’m at pains to articulate why. Like many of King’s fans, I read him as a lonely teenager. I was like a kitten clinging to a magic carpet. But once, when I was extolling the virtues of It to a friend in high school, he asked, “But what is the ritual of CHUD?” And I realized I could not really answer, beyond the sort of icky juvenile sex thing, and in that moment grew up, a little. My honest reading was suddenly not enough.

That said, at least once a year, usually in that time where things are most underwater, I re-read my favorite book of his, The Stand, first published all the way back in 1978. I am apparently not alone in being the kind of person who’d declare it the best thing King ever wrote. “There are people out there who would have been perfectly happy had I died in 1978,” King told the Paris Review a few years back. “I usually tell them how depressing it is to hear them say that something you wrote twenty-eight years ago was your best book.” The only thing he’s asking for, I guess, is that you extend him the same sort of kindness he has always been so quick to offer others.

Previously: Becoming Joan Didion

Michelle Dean writes in a lot of places, now. Follow her on Twitter.

Thirsty Park Slope Moms Will Let Little Beauregard and Synesthesia Run You Down for Beers

“On one occasion, he said, a child on a tricycle collided with his friend’s leg.”

— Come on, people. Slutty Park Slope moms have to get their craft beer on somewhere, even when they don’t have the nanny that day. Let them take the kids to Ted Nugent’s son’s Greenwood Park beer hall and have their affairs in their Volvos outside, they’ve totally earned it. Won’t someone think of the children?

New York City, August 1, 2012

★ A day with hardly any good points, yet not worth being miserable about. The reward for waking up early was a mud-brown western sky, collapsing quickly into gray mist and a shower. The rain clouds went away, came back again, and then lingered with one foot in the doorway, unable to take a hint. A three-dollar umbrella was exactly what it deserved. Come sundown, the western edge of the clouds lifted a little, revealing that the mud sky of morning had been replaced with scarlet Play-Doh. It was an improvement, anyway.

Scholar Finds The Fact That Mitt Romney Somehow Got To Be A Presidential Candidate Totally Amazing

“It is not true that my book Guns, Germs and Steel, as Mr. Romney described it in a speech in Jerusalem, ‘basically says the physical characteristics of the land account for the differences in the success of the people that live there. There is iron ore on the land and so forth.’ That is so different from what my book actually says that I have to doubt whether Mr. Romney read it. My focus was mostly on biological features, like plant and animal species, and among physical characteristics, the ones I mentioned were continents’ sizes and shapes and relative isolation. I said nothing about iron ore, which is so widespread that its distribution has had little effect on the different successes of different peoples.”

— University of California’s professor Jared Diamond gives Mitt Romney The McLuhan Treatment.

Tabloids Go Very Different Directions On This Whole Gay Chicken Marriage Thing

“American neo-Nazis and some top black conservatives have found rare common ground — over Chick-fil-A’s stand against gay marriage” — The Daily News.

“Free speech backers flock to Chik-fil-A” — The Post.

Gorey Went And Got Some

“An earlier version misstated the term Mr. Vidal called William F. Buckley Jr. in a television appearance during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. It was crypto-Nazi, not crypto-fascist. It also described incorrectly Mr. Vidal’s connection with former Vice President Al Gore. Although Mr. Vidal frequently referred jokingly to Mr. Gore as his cousin, they were not related. And Mr. Vidal’s relationship with his longtime live-in companion, Howard Austen, was also described incorrectly. According to Mr. Vidal’s memoir ‘Palimpsest,’ they had sex the night they met, but did not sleep together after they began living together. It was not true that they never had sex.”

'The Mists Of Avalon': Free To Be In Camelot

‘The Mists Of Avalon’: Free To Be In Camelot

(Trill of exultation.) The Mists of Avalon, which I somehow managed not to read until two or three years ago, has a very peculiar place in my heart. Regret and relief, it might be fair to say? I can guarantee that this is a book I would have taken far, far too seriously if I’d read it when I was eleven. As it stands, I completely tore through it and wore more dresses for a while and dragged out my Loreena McKennitt CDs and took a lot of baths with Lush products and pretended to be a servant to the Goddess, but in that awkward, slightly-embarrassed, self-conscious way you do when you’re nearly thirty and still unable to erect productive boundaries between yourself and the written word. Oh, children, but if I’d read Marion Zimmer Bradley’s epic Camelot-ian yarn at eleven… what then? What would have happened to the WORLD?

I would not be here talking to you, that’s for sure. I would have gone Full Hippie. I would no longer be grudgingly purging myself of body hair, I would have a wide selection of natural deodorants (I do hear great things about Soapwalla), I would be living in… hm. That’s an interesting question! I guess I would have stayed in rural Canada, or somehow made my way to Portland, or Austin. And then become either a lesbian barista or one of those people who speak Gaelic. It sounds pretty great, now that I’m thinking about it. Either way, I would have become a pagan. There is not a doubt in my mind that I would have become a pagan. Like, finish the last page, go to the nearest womyn’s bookstore, purchase Wicca for Dummies, and then ALL THE CANDLES. Because this book is a Goddess-y, witch-y, magik-y, glorious mishmash of feminine power and clitorises (clitori?) and heavy green dresses and ancient blah blah. Everything you enjoyed about The Dark is Rising sequence, but with hard-core eroticism. I mean, it’s not all GOOD eroticism, or anything. The book is over a thousand pages long, and it’s just not possible to maintain exclusively erotic sex scenes without mixing it up a little with inadvertent incest, and dream-sex, and sex-with-people-who-are-channeling-deer, and so on.

What DID happen to me, as an adult, as a direct result of The Mists of Avalon, though, was natural childbirth. If you asked me why I gave birth without drugs, I probably said something like “blah blah cascade of interventions, blah blah Ricki Lake, blah blah baby can do drugs in college like non-God intended,” but the real answer was “because I really, really love The Mists of Avalon, and wanted to insert a Bad-Ass Goddess note into my birthing experience.” It pretty much worked, too! I mean, at a certain point (I am not necessarily endorsing the decision to eschew the epidural; it is kind of a clusterfuck), all that weird stuff does kick in. So, if you’ve ever had any curiosity about how it would feel to have your brain come apart and transform you into an animalistic, primal creature who taps into your inner (NOT GODDESS, YOU DO NOT BECOME A GODDESS) vole or ferret or some kind of tiny burrow-dwelling creature that writhes and moans and crawls, natural childbirth is for you. Okay, I think I’m making it sound really unpleasant (which it totally is!), but I guess it is also transformative and powerful and stuff. At any rate, when I was going through transition, I had this full-on hallucination that I was Morgaine, fucking the Horned God at the Beltane Fires, which is what happens when you become actually insane from physical discomfort. I am just making this sound better and better!

Anyway, The Mists of Avalon. For the un-initiated, it is a retelling of the Camelot narrative through the experiences of the female characters, with a whole “collision of hawt pagan spirituality with the creeping menace of lame, sexless Christianity” thing that gets eventually mostly worked out with “oh, well, if people are willing to just be cool, then the Virgin Mary could be a face of the Goddess, and maybe Avalon still exists in our hearts and for our super-dope priestesses.” That part is kind of great, though, because I used to always be wandering around popping off about “the Dark Ages,” until I had this boss medieval lit professor who pointed out that, to paraphrase, the world completely sucked for everyone until about fifty years ago, so acting like that particular era was Dark is a little silly, like “and then there were more oil paintings, and there was much rejoicing, but you were still all covered in boils and farming shit for potatoes.”

If you’re a The Mists of Avalon virgin, you may become slightly perturbed by your inability to keep characters straight. I mean, no offense to Marion Zimmer Bradley, who I would totally make Pope, had I my druthers, but, good gravy, somewhere between Morgaine, Igraine, Gwenhwyfar, Morgause, Viviane, Nimue, and Niniane, it becomes a bit of a task to remember who is a Good Witch and who is a Bad Witch (joke! everyone is both awful and okay). And those are just the ladies! The men are even worse, particularly since some of them are their own uncles and there’s some serious pansexual buffet action to boot. Which is the other nice thing about The Mists of Avalon, right, loads of free-to-be-you-and-me goodthinkfulness.

Like all books that try to explain that having magical powers is a double-edged sword, and a curse, and not something to be wished for or taken lightly, you don’t really buy it. Not that the idea of putzing around Avalon in service to the High Priestess forever sounds great, or anything, but obviously having magical powers is awesome and pretending otherwise is a mug’s game. Speaking of the High Priestess of Avalon/Lady of the Lake, it’s good to point out that in this take on Arthurian legend, both “Lady of the Lake” and “Merlin” are like “Shamu,” i.e. positions held in turn by different individuals. Just to confuse you further? And it’s long. Whoo, boy, it’s long. Can we take a minute to mention that very, very classy books and trashy books alike are often really, really long? Like overlapping circles between A Song of Ice and Fire and A Dance to the Music of Time. Long books are the best, though, especially if you have the problem establishing boundaries between fiction and life that we discussed earlier. And, you know, if you’re going to become trapped in a work of fiction, why not make it an overblown feminist exploration of Arthurian legend?

Okay, I know people have strong feelings about The Mists of Avalon, some of which might even be negative (grrrr), so let’s get our discussion rolling with the rollowing questions!

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• Ugh, on the back of my edition, they call the character “Guinevere” instead of “Gwenhwfar,” like they think extra consonants are too alienating, but if you’re already reading the book it’ll be too late.

• Did you know that Loreena McKennitt’s “The Mummer’s Dance” is the theme song to a telenovela? (“Corpo Dourado” — it only ran for a season.)

• I think we touched on this briefly during The Secret Circle, but please, please weigh in, ex- and current- pagans.

• Do you like Lush products? I know the store is like Yankee Candle on (oh, I was going to say ‘bath salts,’ that’s funny on extra levels!) meth, but until you’ve exfoliated with “Angels on Bare Skin,” you haven’t LIVED.

• Do you ever wonder if, like “Brooklyn Without Limits” on “30 Rock,” Lush is secretly owned by Haliburton, and the joke is on me for basically tithing my income there when I was young and broke and smelled wonderful and had very soft skin and a permanently-slippery tub due to all the bath potions?

• Have you had natural childbirth? You don’t have to!

• Do you have magical powers? Even tiny, tiny ones like growing your fingernails really fast at will?

• Do you know any magical people?

• If Christianity hadn’t showed up to bum everyone out, do you think we’d all be happily building wicker men and Maypole-dancing to this day?

• What would the JFK White House have looked like if THIS was the version of Camelot they were all into?

Previously: Naked Came The Stranger and Gone With The Wind

Nicole Cliffe is the books editor of The Hairpin and the proprietress of Lazy Self-Indulgent Book Reviews.