Son

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s work appears in The New Yorker and Catapult, and on her Instagram feed. Her first book, A Bintel Brief, was published by Ecco Press in 2014.

Spring Cleaning Isn't Worth It

There’s a Rolled-Up Kleenex Somewhere In Your Apartment And You Will Never Find It

And other answers to questions you didn’t ask.

“It’s Spring Cleaning Time. What’s the best way to get started?” — Clean Dean

I’ve never understood clean people or the need to celebrate the coming of Spring by moving everything around. People who care about cleanliness already dominate the airwaves with their advice about having to be insanely clean at all times. Like if you drop a sock somewhere it must be put in a Tupperware container labeled “Dropped Socks.” And then filed somewhere under “Found Socks: Not My Socks.” With some kind of triplicate paperwork to be filled out.

There are whole rooms of my apartment I don’t go in because I’m afraid raccoons may be in them. We used to have a cat that would warn us when things were awry in our living conditions. Now we think the cat is on their side. It’s all very mysterious.

If I were to clean, it would be because I was looking for a Gumby costume or something. Then I clean only enough to find the Gumby suit under all the other crap I have all over the place. There is a layer of laundry that covers all things in my part of the apartment. Which is weird because I’m usually naked whenever I’m walking around. Sometimes I alternate nudity with trying on different things, seeing if they still fit. Frowning at a sombrero that used to fit me when my head was less swollen from eating cheese. Putting my Lost Dharma Initiative jumpsuit. Sighing that it is a little tight.

If you’re going to clean you should really spend at least two, possibly three, days in bed contemplating the task in the dark with the covers pulled up all the way over your eyes. I cannot find the covers because my apartment is pretty messy, so I use whatever is close at hand. If you still feel like cleaning after those days are up then something must be pretty serious. Your roommate may be trapped under a falling couch. Or you have misplaced a pizza under a pile of old copies of The Economist. In these cases natural instinct just takes over. You dig and dig until you find pizza or bone.

But any other attempt at straightening should not be entered into lightly. While placing something in a closet, you displace the spot for another thing. If you put old clothes in a box, you will find, inevitably, another clothes somewhere else. It is like a Möbius strip of things. And somehow you are always the one who has to do something about the clothes. There is no one else. There used to be a character named Mommy that would help you with such projects. She’s in Arizona. And doesn’t like coming to your apartment because your choices “make her sad.” And yet someone every year for the holidays buys you a giant bag of sweaters and underpants. It’s all very confusing. And should not be contemplated while being upright.

I also clean sometimes when I need enough change for the bus in the morning or quarters to do the laundry. This can be quite fulfilling when it goes right. See, all of this was worth something after all. Saving me from a trip to the ATM, these dimes and nickels. Nickels! They are so thick. And yet so easily discarded. Like tiny, worthless, broken dreams.

The energy you spend scrubbing your abode could be spent contemplating the mysteries of the universe, one at a time. Dust is always falling. Falling over the laundry and and the issues of The Economist. Falling over the $50 life-sized singing Santa I left in the corner. Falling over the Christmas tree that is still up in the very next room. Falling over the living and the pizza. There’s nothing you can do, no amount of scrubbing or organizing you can complete that will change the direction of the falling dust. It is falling when you sleep, when you are at work, when you have slipped into a coma.

If you do have a room that you think needs a little help just push everything off all of the furniture and then push the larger and larger pile of stuff into another room. Perhaps the room you have abandoned to the wild beasts you think might live there. Just push it right into the corner. And then never go in that room again. Unless you are looking for that Gumby suit. Which is apparently just nowhere. Gumby!!

Don’t clean your apartment. Spend the time and the effort clearing your mind of banal, meaningless tasks. Someday we’ll all be dead. Possibly from raccoon bites. Or because we eventually got buried by the crap in our homes. And couldn’t open the front door any more. When that time comes, maybe then and only then should we spend time worrying about cleaning. The rest of the time, just throw it over there. Do you smell pizza? Yeah, so do I.

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works at a bookstore.

Slacker, "Amen To The Lonely"

It just doesn’t get any easier.

It’s rainy, it’s Monday, the same people are still in charge of the country that were in charge of the country on Friday and now they have something to prove. What’s good? Nothing. Maybe this will shake you out of the torpor from which you seem unable to emerge this morning, even if only for a moment. Good luck and enjoy.

New York City, March 23, 2017

★★★ The elevator was full of coughing. Children kicked hard chunks of ice to send them skimming around the schoolyard. Scarves were wrapped tight and knotted. Slowly the sun brought the day up out of the deep pit of cold where it had begun, but the wind still brought the knit hat unbidden out of the coat pocket. The light was piercing. One yellow blossom lay in the tangled mat of a limp and flattened planting of daffodils.

Goldfrapp, "Moon In Your Mouth"

Silver Eye, Goldfrapp’s new one, is out next Friday. Here’s the third track they’ve shared from it thus far and now I hope we do make it another week just so we can hear the rest. The sounds in particular here are so excellent that I am willing to overlook the lunar content. Enjoy.

Getting to No

Taking a page out of Paul Ryan’s old D.A.R.E. notebooks

Senator Schumer’s staffers were all lazing around, playing Would You Rather. It had been a long day on the Hill, as usual. They were cracking open Bud heavies and happy, for once in a long time, because their boss had promised to do the right thing: filibuster Judge Neil Gorsuch.

Chuck Schumer barged in, cocky as Foghorn Leghorn. “I did it guys. I did what you wanted me to. I stood up to Mitch McConnell,” Chuck said.

“We got the New York Times alert!” The staffers clinked their bottles again. The one they all called Fuller knocked the bottom of his bottle against the mouth of Marnie’s bottle, so that beer flowed like a foam party.

“Now how are we going to do this?” Chuck Schumer asked, avoiding his temptation to set up Fuller and Marnie. “How are we going to get the fence sitters to no?”

“Leave that to me, boss. As a former Bernie Bro I know how to say no.”

“Yes, sure, Fuller. But we need a game plan. We need to actualize the nos. A step-by-step guide for my colleagues who aren’t used to saying the word.”

“I have an idea,” Marnie said. She whispered to Fuller, “Remember the D.A.R.E. program? Eight ways to say no to drugs? What where they…” Marnie was already Googling on her phone. “Here they are.” Marnie tilted her phone into Chuck Schumer’s face.

“These might work. Fuller, print this out.” Schumer handed Fuller Marnie’s phone. “Make enough copies for the caucus and have them laminated. Actually make hundreds. I want to wallpaper the Senate with these. In the dining room. When Senator Kaine is ironically slathering his burnt steak in ketchup I want him reading these. In the gym. When Senator Feinstein is walking her 10,000 steps on the treadmill I want her reading these.”

“Does it matter that Nancy Reagan probably came up with the list?” Marnie asked.

Chuck Schumer wasn’t listening. “Marnie, let’s go. Fuller, meet us in Senator Bennet’s office. President Obama said that Michael could lead us into the future. Well, here is his chance.”

Chuck Schumer and Marnie stood in the doorway of Michael Bennet’s Senate Office.

“Senator Bennet, where are you on Neil Gorsuch?” the Senator from New York asked.

“Chuck, you know he is from Colorado like I am. I have my staff out in the district this week, going to craft breweries and ski slopes to temp check my constituents. I haven’t made up my mind yet.”

“Perfect. We came here to teach you how to vote no,” Chuck Schumer explained. “Marnie, pretend you’re Judge Gorsuch.”

“I am a judge who wants all truck drivers to work for free and in the blistering cold. Until, that is, they are replaced by self-driving trucks. Will you please put me on the Supreme Court?” Marnie asked, deepening her voice for effect.

Fuller arrived with the laminated print-outs. Chuck Schumer handed Senator Bennet a guide.

“It’s very simple. Just pick one of these strategies.” Senator Schumer handed a laminated guide to Senator Bennet. “You can do, let’s see.” Chuck Schumer fumbled for his glasses. “Marnie, can you read these for my colleague from Colorado?”

“Number one. Saying, ‘No thanks.’” Marnie said. “So that’s like — ”

“Do you guys think parroting Nancy Reagan is what we need to be doing right now?”

“Nancy was a dear friend,” Chuck Schumer lied. “Marnie, keep reading, please.”

“Number two. Giving a reason or excuse,” Marnie said, pointing to the list. “If someone asks you if you want a beer, you could say, I don’t drink beer. As your reason. But in our case, you could be like, no, I won’t vote for Gorsuch. And your reason could be, God, there are so many.”

“Because he hates disabled children,” Chuck Schumer offered.

“Chuck,” Senator Bennet said.

Chuck gestured to Marnie to keep reading.

“Number three is: repeat refusal, or keep saying no. This is also known as the Broken Record method.”

“We brought a special guest for this one. Senator Klobuchar, please, come in,” Chuck Schumer stage managed.

“I’m Judge Gorsuch. I’m a complete asshole. Would you vote to confirm me?” Fuller, live-action role playing Neil Gorsuch, asked.

“No,” Senator Klobuchar said.

“Come on!” Fuller urged like he was used to doing so.

“No.”

“Just try it!”

“No.” Senator Klobuchar said, stamping her feet.

“That’s perfect, Senator Klobuchar,” Marnie continued. “Do you understand, Senator Bennet?”

Senator Bennet was typing out an email to his chief of staff to reschedule his fundraising calls because his colleagues were wasting his time again.

“Number four is walking away,” Marnie said. “Okay, this is a fun one. It’s where you say no and walk away while saying it.”

Senator Bennet rolled his eyes. “My issue isn’t so much how to say no as it is whether to.”

“That, conveniently enough, sounds like number five,” Marnie said, holding her ground. “Which is changing the subject. Senator Klobuchar, we need again you for this one.”

Fuller and Senator Klobuchar broke past Senator Bennet and then scuff jogged into the center of the room.

“Let’s smoke some marijuana and then why don’t you vote to confirm me.” Fuller said, larping Neil Gorsuch once again.

“No. Let’s watch my new video and vote to confirm Merrick Garland instead,” Senator Klobuchar said. “I’m not sure ‘video’ works here?” she whispered to Marnie and Chuck Schumer.

“It’s fine, Klobs,” Fuller said to Senator Klobuchar as he tried to bump her fist with his.

Marnie made a note to excise the word ‘video’ from the how-to-say-no guides.

“Number six is avoid the situation. D.A.R.E. says, if you know of places where people often use drugs, stay away from those places. If you pass those places on the way home, go another way.” Marnie paused. “How would that translate in the Senate?” she asked Chuck Schumer.

“That’s the easiest one! Don’t show up to vote!”

“I can’t avoid a Supreme Court nomination vote,” Senator Bennet said. “That’s like one of our basic responsibilities as Senators.”

“Okay, then how about number seven? Giving a cold shoulder,” Marnie offered. “Senator Klobuchar?”

Amy Klobuchar scooted to the center of the room again.

“Hey! Do you want to smoke and then vote to confirm me?” Fuller-as-Gorsuch asked.

Senator Klobuchar stood silently for several beats.

“This is me ignoring Neil Gorsuch,” Amy Klobuchar explained to Michael Bennet.

“I can’t do that,” Senator Bennet said. “We sometimes run into each other fly fishing or performing other rugged activities about Colorado. I can’t ignore him.”

Marnie furrowed her brow. “Last one, then. Number eight. Strength in numbers.” Marnie cued to Senator Schumer to open the door. “The idea, I think, is that there’s power to be derived from solidarity.”

Senators Sanders, Warren, Franken, Harris, Booker, Murphy, Brown, Gillibrand, Durbin, and Duckworth entered the office, clapping in unison.

“Okay, now this is me giving you all the cold shoulder,” Michael Bennet said as he walked away.

“No, that’s you walking away, Michael. Number four,” Chuck Schumer said. “The strategy you mocked.”

“Come on, Michael. We need this,” Cory Booker pleaded. He and Dick Durbin mock tackled Senator Bennet. Fuller jumped into the scrum. “Strength in numbers!” they chanted.

“Strength in numbers, Michael. Please join us,” Chuck Schumer begged, his hands raised as if in Christian prayer. Then he repeated, “Join us” another forty-eight times, like a very broken record.

None Of Us Will Change Our Minds About Trump Or Any Other Fucking Thing

None of Us Will Change Our Minds About Trump or any Other Fucking Thing

Arie Kruglanski and the rigidity of belief.

Let’s forget, for a little while, about Donald Trump’s lies. There are so many, ranging from the asinine to the near-sublime, that we probably won’t miss any genuine whoppers if we ignore the president’s unrelenting dishonesty for a few minutes. As for the litany of cringe-worthy mistakes and miscues that have characterized Mr. Trump’s first two months in office, where should we begin? With the misspelling of N.A.A.C.P. co-founder W.E.B. Du Bois’s name in a Department of Education tweet?

With an obvious typo on Trump’s official inauguration poster?

Or with my personal favorite (so far): Trump and the RNC paying tribute to Abraham Lincoln by tweeting out a dreadful, saccharine, fridge-magnet quote and wrongly (of course) attributing it to the 16th president.

It’s almost enough to make a fake-news junkie believe that Trump and his pals are intentionally making themselves look lazy and dim-witted, as a kind of smirking pledge to their proudly incurious base:

See? We’re not all that interested in books or history or foreigners. That shit is for ivory-tower eggheads and losers who pretend to like “Wait Wait … Don’t Tell Me!” So we can’t spell. So what? Fake news! Build a wall! Trucks! Trucks!

But, okay, just … forget all that. Let’s focus, instead, on a more pressing reality: namely, the unlikelihood of the president’s backers ever “converting” to the anti-Trump camp. If Donald Trump’s routine debasement of the Oval Office has not chipped away at his popularity among his hardcore fans, no amount of prodding, cajoling or accurate, triple-sourced reporting will change their minds. Because here’s the thing: whether we consider ourselves conservative or liberal, radical right or radical left or middle of the road, very few of us ever change our minds once we’ve settled on what we believe is the truth about an issue, scandal or public figure.

Arie Kruglanski, a professor of psychology at the University of Maryland, has spent much of his decades-long career examining the ways in which people form beliefs and judgments. He has crafted a theory of what he calls “lay epistemics,” i.e., the study of how individual thoughts create subjective knowledge. In Dr. Kruglanski’s view, a craving for certainty drives much more of our decision-making than any of us want to believe or admit, and times of crisis and polarization only serve to ratchet up our craving for that certainty.

Born in Poland in 1939 — a bad year everywhere, of course, but murderously abysmal in Poland — and raised in a Jewish ghetto, Dr. Kruglanski knows a thing or two about both crisis and polarization, as well as the sway that demagogues can exert on individuals, nations and eras.

As a young man, Kruglanski was attracted to and inspired by Freud’s work on unconscious motivation. When he studied psychology at the University of Toronto in the mid-1960s, he found the field dominated by neo-behavioristic theory and the study of animal learning. “This was initially disappointing,” he recently told me, “but I quickly learned that animals, too, are motivated — by hunger and thirst — and to this day I draw on learning and conditioning theory to understand human motivation. To my mind, motivation is the force underlying most of human action, and understanding it is the key to successful interventions to change behavior” — preventing individuals from committing violence, for example, or convincing people to study and to acquire education.

“The basic understanding that psychology has come to embrace,” Kruglanski said, “is that our opinions, impressions, and attitudes are ‘motivated.’ In other words, our opinions are not formed by information alone, because information can be manipulated and distorted. The dog that wags the tail of information is personal motivation. We assume we want the truth, but very often we want something else: to make a decision so that we can move on. Certainty is critical to this process, and the dynamic applies to everyone; we all hold views and make decisions based on our motivations.”

The present-day political climate in the United States, alas, provides for an almost textbook environment in which to watch Kruglanski’s theories play out on a grand, unsettling scale.

“For example,” Kruglanski noted, “if I have a strong motivation to see and defend Donald Trump as an admirable president whose administration will be beneficial to me, my family and society as a whole, then any counter-arguments will slide off of the position I hold, like water off a duck. Anything contrary to what I believe with certainty will be minimized or ignored.”

Kruglanski made frequent use of the term “closure” when discussing the process of formulating one’s worldview through the lens of motivation, rather than through a cool-headed gathering and weighing of information. I asked him if his use of the term is categorically different than the sort of pop-psychology way that many of us have come to speak of closure: that is, working through emotional trauma and accepting that something terrible has happened — the death of a loved one, the end of a relationship — so that we can finally move on.

“No, it’s not that different at all,” he said. “Prior to making a decision, we formulate a knowledge that we’re confident about.

“Say you don’t know who is responsible for the murder of someone you cared for deeply. You’re paralyzed. You can’t move forward. But once the killer is found, tried, and convicted, you have the answer, you have certainty about what happened and you can put it behind you and you can move on. That’s an extreme case, of course, and there is far more complexity involved in moving on from something so horrific — but there’s a kind of elemental commonality there between those two examples of closure. In each case you gain a kind of knowledge. You’ve found an answer, or formulated a confident knowledge about a given question that allows you to act.”

This notion that a quest for certainty drives not only our decisions but our personal politics might be unnerving to those who take pride in getting their news from more than a handful of sources. From Kruglanski’s perspective, information is just one piece — and hardly the keystone — of the edifice making up our private belief systems.

“Most people assume that information is what creates knowledge,” he said. “This is not so. Information can be warped and suppressed. Take death, for example. What can be clearer than death, right? But even death can be denied. People were led into concentration camps where it was readily apparent to anyone who cared to see that they were going to die. And yet they assumed and believed what they were told. That they were only going to showers. So we see that the human mind is capable of tremendous distortions, and it’s all in the service of our own motivations.”

For those of us who have long been seeking arguments that might convince Trump supporters that their man is a thin-skinned totalitarian paranoiac surrounded by far-right cretins, moral bankrupts and probably a few traitors, Kruglanski’s theories could turn out to be liberating. After all, if people make decisions and hold beliefs based not on information, but out of a desire for certainty, then we can safely forget about changing the minds of millions and millions of fervent Trumpkins. It’s never going to happen, just as it’s unlikely that Trump opponents will one day wake up and suddenly “get” why he is such a charismatic and trustworthy leader.

For my part, I’ll take my own certainties and those of my neo-liberal (that’s right, I said it) compatriots over Steve Bannon’s, Stephen Miller’s, Kellyanne Conway’s or Paul Manafort’s any day. May the better motivations of our nature win.

We Got Annie

The Parent Rap

When I was a child, maybe 5 years old, I went to see the first movie I ever recall seeing in a theater. My grandmother, my mother’s mother, took me to see Annie, which came out in 1982. The occasion felt like well, an occasion. As I recall, I dressed up. It was raining and the movie I saw enraptured me. We emerged from the film — probably a matinee — and I was surprised to see that it was still daytime. Before, I’d clung to “Sesame Street” and Mickey Mouse; now, I had Annie. It was my first step, tenuous as it was, towards thinking like an adult.

This was, of course, mostly before you could watch movies on demand at home, so instead of seeing the movie a thousand times, I was reduced to playing, over and over, the recording of the soundtrack. To me, more than anything, Annie has always remained mostly about the songs. I also had a book of stills from the movie that I pored over, learning the names of the orphans and the other minor characters.

Annie the film was based on a Broadway play of the same name which debuted the year that I was born, 1977. I didn’t know this, nor did I know that the play in turn was based on a comic strip, Little Orphan Annie, from 1924, the year that my grandmother was born. I didn’t know any of this. I didn’t know that the film was directed by John Huston, who directed some other movies which would later in life be favorites of mine: The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The Misfits.

I grew up thinking that Albert Finney was always bald, and that he was Daddy Warbucks; when, in high school, I discovered The Rocky Horror Picture Show, I screamed, “that’s Rooster!” when I saw the sweet transvestite roll onto the screen. Bernadette Peters and Carol Burnett and Ann Reinking were to me, not accomplished Broadway performers and comediennes, but Lily St. Regis, Miss Hannigan, and Grace Farrell. They always will be.

So it was with some excitement that, several months ago, I decided to try showing Annie to my three-year-old daughter, Zelda. She’s a bit of a song and dance person, I said to myself, I bet she will like this. And she did.

She took to Annie in a way I could not have predicted. She became obsessed with the songs, she knows the dance routine from “It’s A Hard Knock Life,” carrying buckets and rags around, flopping on the floor, gesticulating wildly. Some days, we wonder what we have invited into our home. She insists, sometimes, that we refer to her as Annie. She renamed our dog Penny: she now answers to ‘Sandy.’ Occasionally, I answer to “Miss Hannigan.”

And even though Zelda can watch the movie any time she wishes, because times have changed and we have Netflix now, Annie is mostly the songs. But watching the film with her — and she is agnostic, she will watch any version, though the 1982 one owns her truest affection — I see it now with different eyes. It is, I must admit, the one thing I allow her to watch which is probably a bit above her age demographic.

I didn’t know until recently that the movie itself is often considered by critics to be “not good.” To me, it is perfect. The songs are brilliant, the choreography lovely, the casting is genius. I admit that I see all of this not with the eyes of a critic but through the thick glasses of nostalgia, and yet, I know that this movie has real artistry to it.

It’s also not really, when you watch it, a movie that is by our standards today very child-friendly. It’s easier, actually, to see Annie as part of a longer history of children’s stories where, inevitably, adults are sort of uniformly complicated, unwieldy, and often bad. Annie is pretty unapologetic about that: the kids are smarter than the adults, who are often menacing drunks. Miss Hannigan is a pathetic drunk government employee, her brother Rooster and his girlfriend Lily are criminals; Daddy Warbucks is a Republican, a self-made billionaire without any formal education. He’s a capitalist, but one who hangs out with FDR. Annie almost dies in the movie, saved by Warbucks’s body man, Punjab, played by the insanely awesome Geoffrey Holder, who I knew as a kid as a spokesman for 7Up. What Zelda makes of all of this — of the menacing adult world punctuated by scruffy, know-it-all kids, I can’t be sure. She’s only three, after all.

I was a little older than her when I first encountered Annie, and I distinctly recall wanting deeply to be an orphan. I didn’t have any problem with my home life (not yet) but the possibility of being a single being, alone in the world, was deeply fascinating to me. Annie, the protagonist of the film, makes hard decisions several times in the movie. She’s the moral center of a film that is deeply, complicatedly female driven. She is offered the wealth and comfort of Warbucks’ mansion when Grace — who is, of course, in love with Oliver Warbucks — convinces him to try adopting Annie, but she rejects it in favor of trying to find her real parents, whom she wrongly believes to still be alive. Children often reject safety for what they really want and, though that comes to seem foolish to us as we move towards adulthood, the nobility of it is apparent in a film like Annie. Annie’s righteousness (which yeah, can sometimes be a little grating) is most evident in her conversation with Franklin Roosevelt and Warbucks, as she tries to convince her adoptive father to get on board with the New Deal. Ridiculous? Yes.

But what’s most ridiculous, in 2017, that a Depression-era movie resonates with a little girl born in 2014. And it does. Even the more complicated themes are not lost on her. To hear her belt out “who cares what they’re wearing on Main Street or Savile Row,” is a true joy but it is also weirdly affecting to have her question me, to accept harsh realities she has never heard before. “Some babies don’t have a mommy or a daddy, that’s called a orphan,” she declared one night before bed. Another morning she said simply, “I’m glad I have parents.”

We both love Annie: I’m just glad that, unlike her mother, she doesn’t yet want to be orphaned. When I was in college, I worked for several years waiting tables in a restaurant. It was a fancy place, and though I liked all my co-workers, I kept mostly to myself. One night, I let the owner of the place, a big guy with a big personality, know that my father and a group of people were coming in. “You don’t have to do anything special, just say hi if you can,” I said meekly.

“You have parents?!” he said. “I always took you for an orphan, I guess.”

The Parent Rap is an endearing column about the fucked up and cruel world of parenting.

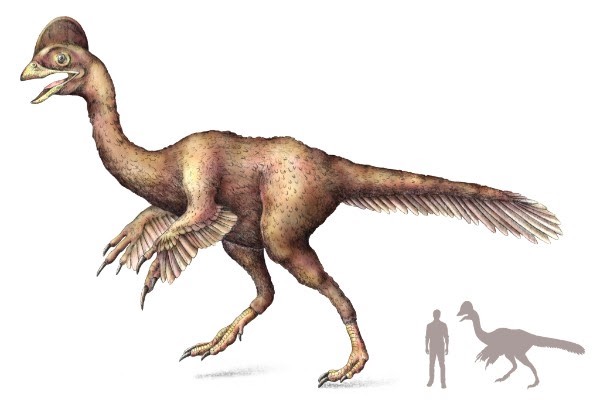

> Fake dinosaur news

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

BREAKING: These dinosaurs are helping their injured dinosaur friend get home to his dinosaur wife and family.

THIS JUST IN: This dinosaur is haunted by the specter of a ghostly, miniature version of himself and a bipedal creature that is the constant companion of the ghostly, miniature version of himself.

COMING IN NOW ACROSS THE WIRE: Jesus was a dinosaur.

UPDATE: Dinosaurs are outwardly very critical of smoking but if you’re out drinking with them they will 100% try to bum a cigarette off you in the back alley.

BREAKING NEWS: Dinosaurs are not good dancers.

JUST IN: Dinosaurs were not anime villains, as much as contrary evidence might suggest.

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.