Giant Lady Robots Fight Each Other Because Why Not

“Three years in the making, the Robot Restaurant cost almost 126 million dollars to build.”

— I feel a little better about the Freedom Tower now.

U.N.: "There Are Some Hellholes Even We Won't Venture Into"

“The United Nations scoffed on Friday at claims by a judge in Lubbock County, Texas, that U.N. troops could invade the southern U.S. state to settle a possible civil war, which the judge warned could be sparked if Obama is re-elected in November.” [Via]

The British Invasion... Again: The Battle Begins

The British Invasion… Again: The Battle Begins

by Robert Sullivan

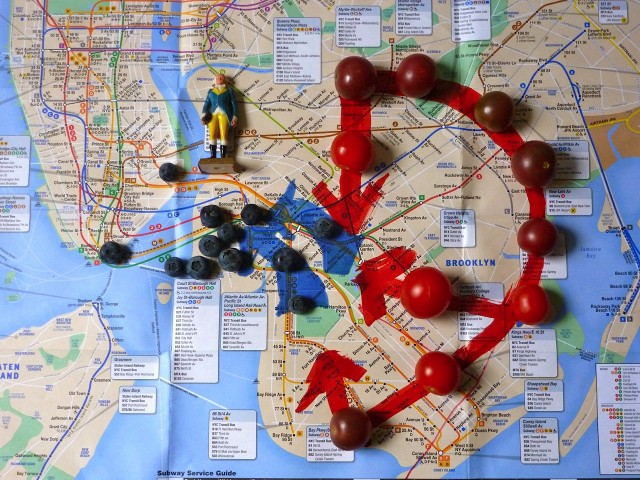

Day four in a series exploring how the trail of the Battle of Brooklyn would pass across modern-day New York. In photo here, the blueberries represent the American side, the cherry tomatoes, the British.

You don’t hear a lot of Monday-morning quarterbacking as far as the Battle of Brooklyn goes. The battle was a loss, but let’s face it: the odds were never good for the Continental Army, and there are not a lot of ways it could have played differently. Sure, there was a general who got sick and had to be replaced at the last minute on the American side, and maybe that was a factor; there were also numerous points at which Americans were asleep at their posts, either literally or figuratively. But even if Washington had managed to win (or not lose), he’d likely have been beaten out of New York eventually, anyway, as he was by fall. Things would not look at all promising for the American side until Christmas, when Washington crossed the Delaware. Another reason you don’t hear a lot of Monday morning quarterbacking is because not a lot of people care. Like I said, it was a loss, as opposed to a glorious victory.

But the actual battle began on this day in 1776, five days after the British landing, and it began with watermelons. The British and the Americans skirmished in the dark in a watermelon patch, where British soldiers were eating, yes, watermelon. (The watermelon patch was planted next to a tavern that, according to historian John Gallagher, was frequented by tourists who came to the spot to see a large rock that was said to resemble the devil’s footprint, a rock that has since gone missing.) Why were the soldiers eating watermelon? Because watermelon was, as now, in season, though if you factor in climate change ours might be in season a little earlier now. Remembering the Revolution is, if you ask me, all about the seasons.

Let’s look at a subway map to get our bearings on where this all went down. In terms of the subway, Washington and his troops were, roughly put, in the area of the F Train stops at Fort Hamilton Parkway and 7th Avenue, in Park Slope and Sunset Park. The British began marching the night before, and they headed down Kings Highway, along a road running north through Brooklyn that is still called Kings Highway. One group took a left at Broadway Junction , where today you could change for the J,Z, A, C and L lines. Those Redcoats headed straight for the village of Bedford, which is today very hip. The other group took a left at Flatbush Avenue, to surprise the Americans by coming through the backside of the woods that are today woods called Prospect Park. A gun was fired by the Redcoats when they arrived in Bedford.

You can walk these roads today — the city turns out to be really good at preserving old human paths (think Broadway, a former trail of the Manhattan Lenape tribe called Wickquasgeck), and when walk you walk Kings Highway early on a summer morning, and you get to the intersection of Kings Highway and Flatbush, you feel as if an army might have turned left here. You just do, trust me. But in terms of artistic representations, things are limited. There are a few plaques in Prospect Park, but there is no great painting, a la Emanuel Leutze’s “Washington Crossing the Delaware” at the Met. In the 1950s, a Brooklyn historian had an artist from the Brooklyn Eagle draw up a kind of imitation Leutze, and after years of fighting, got it made into a Battle of Brooklyn stamp, in 1951. It shows Washington seated on a horse in Brooklyn Heights, pointing the way forward, and features the inscription, “Washington Saves His Army.” The Battle of Brooklyn-related plaque I miss the most was in Red Hook Lane, on Fulton Mall. The plaque is not only gone; the city recently delisted the street. Red Hook Lane, officially speaking, no longer exists.

Some Battle of Brooklyn reenactments happened over the weekend, but they’re over now. And reenactments are hit or miss for me; they can feel a little stiff, depending on my mood. So I did what I have often done in the past to commemorate the event, which was head down to the Gowanus Canal, and scout it. I started at the top of a little hill, on 3rd Street in Carroll Gardens. I stood there. I looked at this sky this morning, summer morning clouds, perhaps the sort of clouds that appeared then. I imagined running down the slope that is Park Slope, through the marsh that became a polluted canal, and up into Brooklyn Heights. Even with pavement, it’s a slog. It’s a long walk, even if you are not being chased by a British army. You can still feel the little valley. And note: all across the land that became the United States of America, where there were once large, oyster-laden marshes, like the Gowanus Marsh that is now down to the impounded Gowanus Canal, there are now factories, industrial sites, sports arenas, airports and polluted creeks.

Then tonight, I’m heading to a dance performance — a reenactment of the battle with movement, with humans addressing the space. It starts at 7 p.m., and will take place at the head of the still visible (especially if you are coasting on a bike) Gowanus valley, at the F Train’s Bergen street stop. It was choreographed by Paul Benney, a dancer, and a member of iLand, a collaboration of dancers and scientists. I’ll also eat some watermelons, and have some of the last tomatoes of the season for lunch. The blueberries are getting tired, like Continental soldiers about now — they had lost the Battle of Brooklyn by lunch. I need a lot of energy, to get ready for the evacuation that’s happening 236 years ago tonight. After that I’ll head down to the harbor, to keep an eye on the water watching it closely, for signs.

Previously: The Landing In New York, Scouting Old Locations and The General And The Moose

Robert Sullivan is the author of a several books, including Rats, How Not To Get Rich, and the Meadowlands. His newest book My American Revolution will be published Sept. 4 and is available for preorder.

Where It Begins

“[Penn State] has pulled the classic Neil Diamond song, ‘Sweet Caroline’ from its musical program for the upcoming season, according to a report by the Altoona Mirror. School officials made the call to pull the plug on the popular sports anthem after expressing concerns about the nature of the song and its lyrics. The song’s chorus features the line ‘Touching me, touching you’ and was written to describe an 11-year-old Caroline Kennedy.”

New York City, August 26, 2012

★★★ Appropriate wallpaper. Going outside wasn’t a chore; neither was going back inside. The clouds were mostly proportionate to the sun. There was one stray big one that an excitable child could believe might have a bit of rain in it. By the time the excitable child made it into the 72nd Street subway control house — the newer one, on the uptown side of the street — the cloud had gone away, without having cast enough shade to ease the heat under the glass roof. Further down Broadway, a free sample spoon of gelato was fluffy, its surface unmelted by the ambient air. The employee running in and out to hawk the samples was wilting a little, though.

My Doomed Attempt To Make Jjajangmyeon At Home

by Ben Choi

A series about foods we miss and our quests to recreate them.

When I was little my father used to take me and my brothers into L.A.’s Koreatown after Korean Church. We would often stop by the Joonggook jip (Korean-Chinese restaurant) for a steaming bowl of my favorite lunch, jjajangmyeon, a roasted black soybean sauce served over hand-pulled thick wheat noodles. My father would always tuck a paper napkin under my chin, since the inky sauce was liable to leave flecky dark-brown stains on my white Sunday shirt.

Now I’m grown, and I no longer feel comfortable wearing a makeshift bib in public. To avoid visible stains I always wear black when I go out for jjajangmyeon. Wearing black is doubly a propos, because I’ve begun mourning over the inevitable decline of this tasty noodle dish. In its most authentic form at least, the lost food I feel so nostalgic for is heading quickly towards being truly lost — towards extinction.

I know I’m being a little dramatic. Jjajangmyeon is one of the most popular foods in Korea and in Koreatowns across the globe. It’s the number-one South Korean delivery/takeout food, as omnipresent as pizza is in the U.S. But I’ve found it harder and harder to find a good bowl of it, and, by my observation, jjajangmyeon has changed over the years. It used to be a cultural touchstone, a manifestation of the best parts of assimilation. Chinese immigrants adapting their cuisine to fit the tastes of their valued Korean customers. Now it’s perceived as a Korean dish, and it’s being served up primarily by Koreans. What used to be a process has become an endpoint, a product. Imagine going into typical American-Chinese takeout place and seeing some white guy manning the wok. When the last ethnic Chinese chef who was trained in Korea hangs up his apron, that’s where we’ll be.

In setting out to recreate my childhood favorite, I know I’m doomed to failure. At its heart jjajangmyeon is immigrant street food, and my homemade version is bound to be, like me, too Korean and too American. I’m certainly not going to be able to hand-pull the noodles, or ferment and roast the soybeans for the sauce. I’m relying on store-bought Korean products, so it’s on the flavor details and textural niceties I’m going to concentrate. In the end, though, I’m just like that white guy slinging General Tso’s chicken.

Here’s a little historical background on jjajangmyeon. Immigrants from China’s Shandong province brought their distinctive food culture to Korea about a century ago, during the time of Japanese rule. Over three generations, a legendary hybrid cuisine was developed in the lunchrooms and take-out joints run by these culinarily gifted ethnic Chinese Koreans, and Korean-Chinese food became extremely popular. Unfortunately, in the 1960s and 1970s, under Park Jung-Hee’s military dictatorship, Chinese Koreans were heavily discriminated against, having to contend with laws that limited or outright eliminated their rights to own property, and run businesses. The majority of ethnic Chinese in Korea were forced to migrate, once again, this time mostly to the United States and Taiwan. In the United States, many of these two-time emigres opened Korean-Chinese restaurants in the burgeoning Korean communities of Los Angeles, Chicago, New York City, and Fort Lee, New Jersey. There are some that will tell you that the best Korean-Chinese food is American Korean-Chinese food, and I’m inclined to agree. I’ve always suspected I got in on the good stuff.

What makes jjajangmyeon great is what separates it from other Korean food. Korean food is known for bold, distinct flavors and textures, but jjajangmyeon’s gustatory effect is subtle and cumulative. The salty and slightly sweet sauce, with its little chewy tidbits of meat and vegetables, forms caramelly whole which complements the freshness and softness of the noodles. There’s also a lot less meat here than you’ll find in most restaurant Korean food. And, heck, there isn’t even very much garlic in it.

I’m a bit of a purist about jjajangmyeon. And though I accept that non-Asians can excel at martial arts, I have the conviction that only ethnic Chinese living among Koreans can make great jjajangmyeon. My Korean homies’ll spice it up too much, or make the noodles too firm. Chinese nationals who have not lived in Korea may have the noodle skills, but will lack the insider understanding of the Korean palate. There are, though, fewer Korean-Chinese folks around than there used to be. As we move further from the generations of Korean Chinese that created this dish, fewer of their children will go into the family business, and all that good double-diaspora know-how will go into engineering and finance rather than noodles. Hand-pulled noodles are available in only a handful of joonggook jip in any city I’ve been.

I really feel a sense of loss. The once-thrilling build-up that used to accompany trying a new jjajangmyeon joint has been displaced by a cycle of disappointment not unlike following the mating difficulties of giant Pandas at the zoo. “The sauce is watery at that new place. Ooh, and Pei-Pei has given Ling-Ling a nasty bite on the leg.”

On the bright side, decent homestyle jjajangmyeon is much easier to come by nowadays. The decline of the great, from-scratch, genuine article in restaurants has definitely correlated with an increase in the availability of black-bean paste of quite good quality (I recommend Cheong Jeong Weon (청정원) and Haechandle (해찬들)) and passable factory-made noodles. These allow you to make jjajangmyeon at home that rivals what you’ll find in many restaurants today. In fact, this might be how most places make it now.

I wound up making this recipe three separate times, modifying as I went along. Here are a few things I learned from all the trial and error:

• Uniformity and size of dice is very important. Even ½-inch pieces feel a bit large and tough.

• Definitely make sure to pre- fry the black bean paste. It totally makes the flavor more subtle and complex.

• Don’t use too much starch. It dulls the flavor, and an overly thick sauce won’t adhere to the noodles in the right way.

• Use the right kind of noodles. I experimented with knife-cut and Shanghai style noodles. Definitely use Korean noodles that are specifically for jjajangmyeon. (I know the package says “udon,” but the Korean writing beneath it also says “jjajang.”)

• Quick-rinse the noodles and drain well. Leaving too much surface starch or extra water on them adversely affects how the sauce adheres.

• Definitely finish with sugar and sesame oil. It tempers the saltiness of the sauce.

I was pretty pleased with the recipe I arrived at. It’s about as good as you’ll find in many restaurants. The noodles don’t come close to hand-pulled, or even freshly made machine-cut ones, but they mate with the sauce rather nicely. The sauce is actually quite good. The veggies and meat are about the right firmness, and the flavor and texture come pretty close to the mark.

HOMESTYLE JJAJANGMYEON

(Serves 4)

1 tsp. peanut oil

½ tsp. sesame oil

4 tbsp. Korean black bean paste

1 tsp. peanut oil

½ tsp. sesame oil

½ lb. pork country rib, diced

1 tsp. peanut oil

½ tsp. sesame oil

1 medium white onion (about 1 cup), diced

2 small zucchini (about ½ cup), diced

Korean white radish (about ½ cup), diced

2 cups water

1 tbsp. potato starch dissolved in 1 tsp. water

2 tsp. brown sugar

½ tsp of sesame oil for drizzling

1 Persian cucumber, cut into thin matchsticks

Heat peanut oil and sesame oil together in a small nonstick skillet over medium high heat to shimmering. Stir in black bean paste, combining thoroughly with hot oil. Heat while stirring constantly for about 2 or 3 minutes. Set aside.

Chop pork and all non-onion and non-cucumber vegetables into ⅓-inch dice. You’re aiming for a high level of uniformity in the pieces, so use a very sharp knife.

You want to discard the seeded portion of the zucchini. To do this chop off both ends and slice in half lengthwise, and then slice each half lengthwise again. This creates a 90-degree triangular prism of seeds. Cut it out.

Onions are round, so it will not be possible to get totally uniform pieces, so aim for a ½-inch wide dice at the surface of the onion that way, the pieces will average about ⅓ inch. Cut the cucumber into 2-inch matchsticks.

To brown the pork, heat peanut and sesame oils together in a wok over high heat, to shimmering. Brown pork to about what would be a medium-steak level of doneness.

Carefully remove the pork and set aside, leaving as much rendered pork fat and oils in the wok as possible.

Add Korean radish to hot fat, stirring intermittently but vigorously for 3 minutes. Now add onion and give it the same treatment for 2 minutes. Add the zucchini for just about a minute. Finally re-incorporate the pork to the vegetable mix.

Add water and the black bean paste you fried earlier. Combine well and bring to a boil.

When sauce reaches a healthy simmer, add potato starch slurry.

Lower heat to medium and let the sauce thicken to the consistency somewhere between half-and-half and cream.

Stir in the brown sugar and finish the sauce with a drizzle of sesame oil, about a half-teaspoon.

For the noodles, bring a couple of quarts of water and a healthy pinch of salt to rolling boil. Add about 3 servings of the jjajang noodles, as this should translate to about 4 normal servings. Boil for about 3 to 4 minutes. The noodles should be considerably softer than al dente pasta, but still have some elastic bite to them. Rinse quickly under cold water for just a second or two. You want to get rid of some of the surface starch, but keep the noodles warm. Drain well and portion into bowls. Top liberally with jjajang and garnish with cucumber.

So there you have it. Homestyle jjajangmyeon. Please enjoy. But if there’s a well-regarded Korean-Chinese restaurant near you, I encourage you to seek it out and try the traditional version. Just remember to wear black.

Previously: My Attempt To Make The Perfect Nebraska Runza, How To Enjoy A Beef On Weck When You’re Not In Buffalo and How To Enjoy A Pasty When You’re Not In North Michigan

Ben Choi, who writes this site’s Search For The Next Sriracha column, lives in the Bay Area with his wife Erica and dog Spock.

Economy So Bad Even Racists Are Sympathetic

“The economy is so lousy for middle-income Americans that the same people who chafe at the rise of welfare dependency under Obama don’t automatically default to a ‘get-a-job’ attitude — because they know there are no jobs.”

Life: How Much Longer Do You Have To Keep Doing It?

How many years might be added to a life? A few longevity enthusiasts suggest a possible increase of decades. Most others believe in more modest gains. And when will they come? Are we a decade away? Twenty years? Fifty years? Even without a new high-tech “fix” for aging, the United Nations estimates that life expectancy over the next century will approach 100 years for women in the developed world and over 90 years for women in the developing world. (Men lag behind by three or four years.) Whatever actually happens, this seems like a good time to ask a very basic question: How long do you want to live?

I’ve been thinking about this very basic question for a while now, and weighing all the pros and cons — the fact that life is essentially a series of disappointments, underwhelming events, long waits in lines behind people who could care less about whether or not they are inconveniencing you through their own idiocy, the chance to experience the inevitable decline in your mental and physical abilities, and the opportunity to watch your loved ones die vs. the occasional enjoyable meal or movie that actually isn’t too bad — I’m going to say “28 years.” Which I guess puts me into suffering’s golden time right now. How ‘bout you? Tell us in the comments. Or whatever. It doesn’t matter either way. Nothing does.

Doze And Learn

Apparently you can learn stuff in your sleep. I am always trying to figure out which Hemsworth brother is which, so if someone can arrange to help me get that sorted during naptime, super!

The 'Times' And Occupy

Remember how the New York Times was totally in the tank for the Occupy movement? You don’t? Here’s why.