Money Only Pays the Rent

Dead Can Dance are back. Did you miss them? Salome in the Lincoln Center Plaza! John Reed with Eric Banks! Plus sports, weather and more. (JK not sports.) (iTunes)

Writer Food From A To Z

Writer Food From A To Z

by Jane Hu

For Frank O’Hara, L was definitely for Lunch. He wrote most of Lunch Poems during his lunch hours — pausing, as he put it, “for a liver sausage sandwich in the Mayflower Shoppe” and taking notes on what he’d seen while roaming Manhattan. Eating and writing, eating and writing. I adore the book’s title, not just for its banal literality, but for its figurative (ahem, poetic) potential as well: The volume of poems, small as a subway map, tucks easily into one’s pocket. Like a snack. And the poems, too, can be consumed that way. As O’Hara’s famous “A Step Away from Them” suggestively ends: “A glass of papaya juice / and back to work. My heart is in my / pocket, it is Poems by Pierre Reverdy.”

Poems can be a form of sustenance. But a writer, no matter how high-minded, cannot live by poems alone. And as has been illustrated and explored elsewhere, particular snacks and foods often become intimately entwined with writers’ daily routines. What have been some of these favorites? And what were the make-dos when times were lean? (They don’t call them “starving artists” for nothing!) Let’s run through the alphabet and see.

A is for APPLES

Charles Dickens couldn’t get enough of baked apples — one of his favorite treats. He found beauty in their simplicity, and also believed the baked apple had other virtues as well. In an 1867 letter to his sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth, Dickens writes: “If ever you should be in a position to advise a traveler going on a sea voyage, remember that there is some mysterious service done to the bilious system when it is shaken, by baked apples.” Delicious and magical! F. Scott Fitzgerald also employed the basic apple in his survival strategies. While writing essays for Esquire in 1936, Fitzgerald stayed in a cheap North Carolina hotel where half of his diet was apples.

B is for BOOZE

Has anyone ever told you it’s easier to write after a drink or too? Alcohol can tip the paralyzingly self-aware into loquacity. There are your classic lushes: Hart Crane, Hunter S. Thompson, William Faulkner. Kingsley Amis’ famous “Boozing Man’s Diet,” included here, opens with the caveat: “”The first, indeed the only, requirement of a diet is that it should lose you weight without reducing your alcoholic intake by the smallest degree.”

But what about your more restrained drinkers? Robert Frost loved daiquiris. At the Waybury Inn near — one of his favorite dining spots — Frost would begin every dinner with a daiquiri. But only one daiquiri — never more. John Keats also wanted to get the most out of one drink: His fondness for claret caused him sometimes to place cayenne pepper on his tongue, to enhance the drink’s flavor.

C is for CHAMPAGNE

Oscar Wilde’s love for drink didn’t stop him from indulging in it. Wilde was wined and dined during his 1882 American tour, with servers instructed to bring him champagne “at intervals” throughout the day. As noted here, even in prison, Wilde ordered cases of his favorite bottle (an 1874 Perrier-Jouët) straight to his cell. Transcripts of Wilde’s April 1895 cross-examination confirm his devotion to champagne:

Mr. Oscar Wilde: Yes; iced champagne is a favourite drink of mine — strongly against my doctor’s orders.

Mr. Edward Carson, QC: Never mind your doctor’s orders, sir!

Mr. Oscar Wilde: I never do.

D is for DEXEDRINE

For Muriel Spark, Dexedrine was at once an appetite suppressant as well as a dieting aid. The author of Girls of Slender Means took the slimming pill for the first half of 1954 — a period of postwar food rationing. After more than half a year on the amphetamines, she started to have delusionary visions, schizophrenic-paranoid hallucinations not unlike those she depicted in The Comforters. Reading T. S. Eliot’s The Confidential Clerk, Spark believed that the play held codes targeted at her, and spent pages upon pages puzzling over the text. Friends described observing Spark as “watching someone using spiritual crossword puzzles.” Alan MacLean — Spark’s former editor — would later tell the New Yorker that she was “really quite batty” during the Dexedrine phase.

E is for ÉCLAIR FILLINGS

While Colette aspired to thinness (she devoted many a summer to shedding weight), girl still knew how to enjoy some pleasures. And there were some indulgences she just wouldn’t do without. Claude Chauvière, one of Colette’s secretaries, looked on with dismay, as her “passive, idle, greedy” employer scooped and ate the filling out of chocolate éclairs.

F is for FRITOS

Food can serve as creative incentive for the writer. Years ago Neil Simon mentioned a habit of rewarding himself for completing a difficult scene with a bag of Fritos. (He also pays homage to the chip in his plays, such as when it pops us as an important plot element in The Sunshine Boys.)

G is for GREENS

From Aristotle to Alice Walker, vegetarians have repeatedly demonstrated that one doesn’t need meat to fuel even the most active of brains. Other notable vegetarian writers: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Agostinho da Silvo, and Jonathan Safran Foer.

H is for HALVA

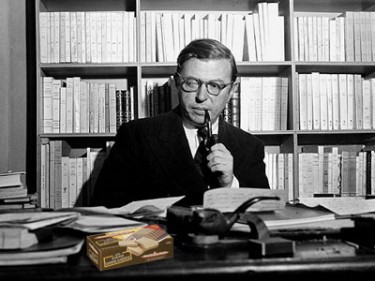

Jean-Paul Sartre was nuts about Simone de Beauvoir, but was nuts about halva more. During his time away at WWII, he craved the dense, nut-based dessert. In his letters to de Beauvoir, he would ask about his beloved treat. “Don’t forget,” he reminds her in 1939 to send two more boxes of halva. Then, in a following letter: disaster. “I was in an excellent mood today, and then I got your books (the Romains) but no halva. Is there another package?”

I is for ITALIAN SPAGHETTI

H. P. Lovecraft adored “Italian spaghetti,” especially with “meat-and-tomato sauce, utterly engulfed in a snowbank of grated Parmesan cheese.” Cheese was important. “How can anybody dislike cheese?” he wrote in a letter to fellow horror writer J. Vernon Shea, “I don’t suppose you would like spaghetti if you don’t like cheese, for the two rather go together.” Lovecraft not only enjoyed the taste of pasta — he appreciated its modest cost. “I have financial economy in eating worked out to a fine art,” he wrote in 1932. “I never spend more than $3.00 per week on food, and often not even nearly that.”

J is for JAVA

Marcel Proust famously once drank 16 consecutive cups of espresso. While Proust ran on java jitters, Gertrude Stein was quite concerned about the effects of caffeine. Though Stein’s doctor prescribed her a cup of coffee each morning, she remained wary of the drink. Stein was always nervous about getting nervous and the very thought of coffee added to this anxiety.

K is for KRISPY KREME DONUTS

Nora Ephron rhapsodized about Krispy Kremes in The New Yorker: “The Krispy Kreme Original Glazed doughnut is yeast-raised and light as a frosted snowflake. It is possible to eat three of them in one sitting without suffering any ill effects.” Ephron especially loved watching the donut machine at work: “The sight of all those doughnuts marching solemnly to their fate makes me proud to be an American. Sue me. That’s how I feel.”

L is for LOAVES

Emily Dickinson and Virginia Woolf were skilled bakers, both specializing in bread. You can even try a few of Dickinson’s original recipes. Percy Shelley — who often dieted on just bread and water — would have enjoyed such company. Shelley found it difficult to walk by a bakery without stopping in to buy a loaf. Rumor has it that he constantly stored bread in his pockets, leaving a trail of crumbs wherever he sat.

M is for MILK

When Molière got sick in 1667, he resorted to a milk-only diet for two months. During the 1830s, Honoré de Balzac went on milk-only diets to combat stomach problems. Franz Kafka was a lacto-vegetarian, also because of digestion complications.

N is for NOTHING

Emily and Charlotte Brontë both had difficulties with eating. Emily regulated her diet, which was described by her sister as “very simple and light.” Meanwhile, Charlotte also voiced difficulties with eating, specifically in public. She especially disliked eating out, which she found a bore.

J.M. Coetzee doesn’t “drink, smoke or eat meat,” and takes long bike rides in order to keep fit. In a 1988 interview, Gabriel García Márquez talked about his “perpetual diet,” which restricted his food intake — whether from willful dieting, or because he simply couldn’t afford to eat. When William Hazlitt was at his poorest, he had quite the irregular diet, often going without breakfast and dinner.

O is for OYSTERS

Anton Chekhov was a fan of oysters. Coincidentally, when Chekov died, his coffin was transported in a freight car with ‘OYSTERS’ in large letters on its side. Walt Whitman, also an oyster lover, often ate them for breakfast. When friend John Burroughs told the poet he ate “too much blood and fat,” he went on to recommend that oysters be dropped from Whitman’s morning menu.

Alternately, Isak Dinesen lost weight with the following diet: oysters and grapes, washed down with champagne.

P is for PLUM CAKE

For one breakfast, Jane Austen sat before a spread consisting of plum cake, pound cake, hot rolls, cold rolls, bread and butter, chocolate, coffee, and tea. Balance.

Q is for APPETITE-QUELLING

When especially hungry while living in Europe, Ernest Hemingway would go to a Luxembourg museum “belly-empty, hollow hungry” to stare at pictures of food. Hemingway felt that looking at Cézanne paintings of food not only helped him not to eat, but also fed his aesthetic appetite too. “I learned to understand Cézanne much better and to see how he made landscapes when I was hungry.”

R is for RABBIT STEW

On her honeymoon with Ted Hughes to Spain, Sylvia Plath packed a copy of Joy Of Cooking in her baggage. With Irma Rombauer’s guidance, she was able to make Hughes a “delectable” rabbit stew for his birthday. As she set up her life with Hughes, Plath would pore over the cookbook, “reading it like a rare novel.”

S is for SODA WATER

Slightly overweight as a child, Lord Byron became a chronic dieter in later life. Invited to dinner at the home of the poet Samuel Rogers, Byron was offered fish, mutton, and wine — all of which he refused. Upon being asked what he would eat, Byron replied: “Nothing but hard biscuits and soda-water.” Rogers couldn’t provide his guest with these, so Byron finally settled on “potatoes bruised down on his plate and drenched with vinegar.”

T is for TEA

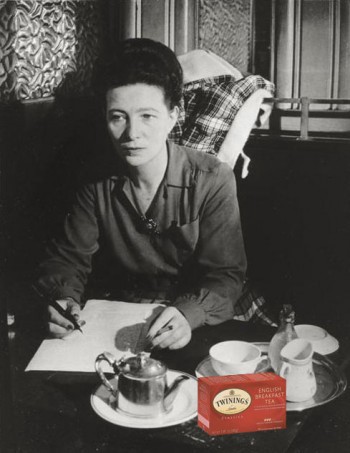

Upon rising, Immanuel Kant would drink one or two cups of tea (always weak). John McPhee and Paul Auster also reportedly start the day with tea; as Simone de Beauvoir did, too. In the late 70s, Stephen King began teaching and set up a routine in order to continue his own creative work in his off hours. Before settling down to write in the morning, King had to have “a glass of water or a cup of tea” by his side. “The cumulative purpose of doing these things the same way every day,” he wrote, “seems to be a way of saying to the mind, ‘You’re going to be dreaming soon.’” Jane Austen, of course, drank tea (though she disliked it with sugar). When working in the morning, C.S. Lewis loved having a good cup of tea brought to him. (He strongly believed that “Tea should be taken in solitude.”) The real question here is: who writes and doesn’t drink tea.

U is for UNORIGINAL

Jack Kerouac loved Chinese food (especially the pork dishes), but his favorite dessert couldn’t have been more American vanilla: apple pie à la mode.

P.G. Wodehouse’s typical breakfast involved a slice of coffee, toast with honey or marmalade, and tea. With this, he would read a “breakfast book,” usually a crime or mystery novel. He would get to work while smoking a pipe (obviously). Lunch usually meant one meat and two vegetables, followed by an English pudding. At around four o’clock, he would join his wife for English tea-time on good china and cucumber sandwiches. Jeeves!

V is for VANILLA PUDDING

Günter Grass has written nostalgically of “the vanilla pudding with almond slivers” that his father used to make.

W is for WAR RATIONS

Most British writers suffered from food (and paper!) rationing during WWII (and afterward, as demonstrated by Muriel Spark). Imported fruits like bananas were especially hard to come by. Once, on a rare occasion when Waugh’s wife managed to bring home three bananas for their children, Waugh proceeded this way: sitting down before the children, he peeled the bananas, slathered them with cream and sugar, and then ate every last one. Whether this illustrates the desperation of living under rationed conditions, or simply Waugh’s generally churlish demeanor, I couldn’t say.

X is for EXTREMES

Franz Kafka believed in chewing food 100 times per minute. In 1912, he called himself “the thinnest person I have ever known.” As a young adult, Victor Hugo would eat half an ox in one sitting — and then fast for three days.

Y is for YOLKS

When living in exile in the Channel Islands, Victor Hugo would rise at dawn and eat 2 raw eggs, drink a cup of cold coffee, then begin writing.

Z is for ZINGERS

Dorothy Parker fed her readers the wittiest zingers. And leading us back to our alphabet’s beginning, she once said, “Ducking for apples — change one letter and it’s the story of my life.”

Related: A Timeline Of Future Events and A Short History Of Book Reviewing’s Long Decline

Jane Hu knows the muffin man.

New York City, August 27, 2012

★★★★ A warm, indifferent sprinkle at noon erupted into a window-thumping downpour. People jumped up from staring at their computer screens and hurried over to stare at the water battering against the glass. A sheet of water covered the landing of the fire escape; drops came spraying in through the top of the doorframe. It was raining inside, the final flourish of a showpiece. The remaining hours to evening were irresolute: a high dome of feathered pure-white clouds, with a low layer of yellowish clouds blowing rapidly north below. Lost mylar balloons flashed, drifting apart from one another, higher than the building tops and lower than a departing airplane.

Trick Yourself Into Thinking You Don't Suck

“If you don’t feel happy, fake it. You wouldn’t constantly burden a friend with your bad mood, so don’t burden yourself. Try holding a pencil horizontally in your mouth. ‘This activates the same muscles that create a smile, and our brain interprets this as happiness,’ [some cognitive psychologist] says.”

— Does this work? I don’t know and I don’t care. The real mystery to me here is why anyone, knowing what they know about themselves, thinks they deserve to feel happy. They don’t. None of us do.

The British Invasion... Again: The Mystery Of The Missing Marylanders' Grave

The British Invasion… Again: The Mystery Of The Missing Marylanders’ Grave

by Robert Sullivan

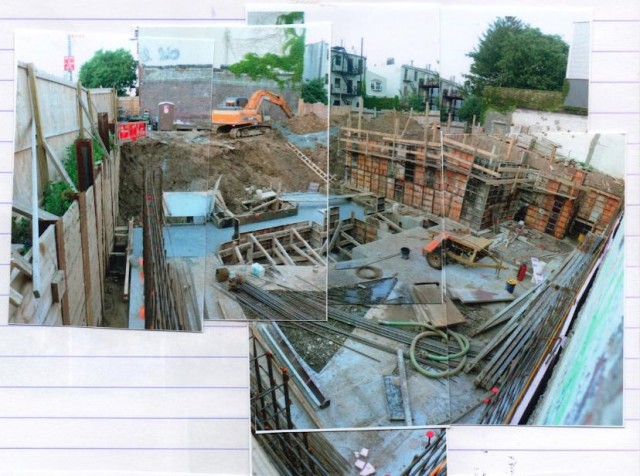

Day five in a series exploring how the trail of the Battle of Brooklyn would pass across modern-day New York. Shown in photo, a potential burial site of the Maryland regiment, near the intersection of 3rd Avenue and 8th Street, that went uninvestigated when it was recently dug up.

The day after the battle, there are dead and wounded all around: 1,000 American soldiers in the woods and the fields all around what is today Park Slope and Greenwood Cemetery, all along the Shore Road that is today in the vicinity of 3rd Avenue and 3rd Street, as well as Pep Boys, Hotel Le Bleu and J.J. Byrne Park. A thousand men were captured. The late John J. Gallagher, the military historian and forensic historian (who is buried on Greenwood Cemetery’s Battle Hill, in view of the harbor and all the field of battle) wrote: “Scattered parties of the living were still hiding in the forests and swamps or trying to make their way to the inner lines around Brooklyn Heights.”

The day before had been a hot summer day, but now there was a summer rain, with lightning and thunder — a storm, that kept the British from sailing up the East River. The British position, after the previous day’s fight, is the opposite of gentrification: the British now control all of the land to the east of Brooklyn, threatening the Manhattan-convenient Brooklyn Heights, where the Americans are held up in their forts and camps. A Rhode Island soldier wrote: “After we got into our fort there came a dreadful rain heavy storm with thunder and lightning, and the rain fell in such torrents that the water was soon ankle deep in the fort.” It was a typical summer rainstorm, much like the rainstorm that was reenacted in Brooklyn this morning, 236 years later.

The big casualties were at what was known as the Old Stone House. The British, under General Cornwallis, were stopped from their advance toward Brooklyn Heights by an American general, Lord Sterling. (His title was disputed in England but Washington, perhaps due to an acute need for experienced military commanders, did not mind calling him Lord.) With a group of about 250 soldiers from Maryland, they attacked the overwhelming number of British soldiers — attacked six times, each time, scores falling dead. George Washington, while watching from what is today Trader Joe’s, is attributed with saying: “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose!” Cornwallis later said, “General Sterling fought like a wolf.”

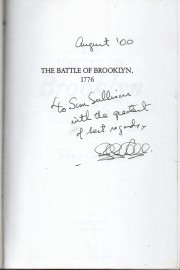

The Marylanders were reportedly buried by the British in a mass grave, and the whereabouts of that grave have long been of great interest to local Brooklyn historians. But it’s not an interest widely shared elsewhere, despite the valor of the Maryland troops having allowed the rest of Washington’s army to escape. Gallagher was occasionally in search of the grave, at the time I spoke to him about it, at a book signing in 2000, when he signed a book for my then 11-year-old son, ancient history.

Every year there is a memorial service, a small group of people coming to Brooklyn from Maryland, as well as Pennsylvania and Delaware. The American Legion post at 9th Street and 9th Avenue has a plaque. But still, the Marylanders feel forgotten.

To imagine where they were it is necessary to picture the Gowanus not as a canal but as a marsh, with famously large oysters. There was a millpond, where water collected to power a mill. There was a tidal aspect, as there is today. To imagine where the Marylanders might be buried, you have to try and picture where the filled in creek ends and where the land on an old Dutch farm would have begun, a difficult task. Traditionally, it is thought to have been along 3rd Avenue, near 9th Street. There was a plaque for many years. In 1957, James Kelly, the borough historian of Brooklyn at the time, got the federal government to do a dig along 3rd Avenue, near 8th Street, in the vicinity of the traditional burial site. It was a dream come true for Kelly. “No place is more sacred in America,” he wrote. He was with the archaeologists during the dig, when they found nothing, with the exception of old clay pipes and foot-long oyster shells. Recently, an historian was in the Times saying that there should be a dig a few yards away. “The evidence is quite strong,” he told the reporter. “I’m confident enough that I tell everyone I know.”

I know how he feels. A couple of years ago, when a building went up a few dozen feet away, construction crews began to dig a large pit — it was, I realized when I passed it, in the same general vicinity as the traditional Marylanders burial site. I called every archaeologist I knew. Nobody was interested. The hole got deeper. I looked for signs — of what I knew not. I called more people. I took photos. At last, construction began, the hole filled. It was depressing, to say the least, as it is now, when I think of it. I always wonder if there are ghosts in the underground parking lot.

Previously: The Landing In New York, Scouting Old Locations, The General And The Moose and The Battle Begins

Robert Sullivan is the author of a several books, including Rats, How Not To Get Rich, and the Meadowlands. His newest book My American Revolution will be published Sept. 4 and is available for preorder.

Jennifer Egan, Saboteur?

Jennifer Egan’s “recent sci-fi excursions expose her not as a writer resigned to the waning importance of literature, but as a literary ‘luddite’ willing to take things to the next level, to begin a sabotage.”

— I’m not buying all of this but I like this as an idea.

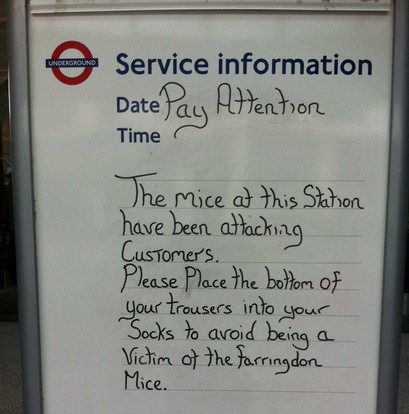

Knifecrime Island Under Attack From Plague Of Toe-Nibbling Rodents

Britain: If the cats don’t get you, the mice will:

[A] gang of rampaging mice appear to be striking fear into the hearts of London commuters, after being reported to be nibbling their toes. Passengers at Farringdon station were left puzzled after an official-looking sign warned the mice had been “attacking” customers. The handwritten notice advised: “Please place the bottom of your trousers into your socks to avoid being a victim of the Farringdon mice”.

Oh, August, you cannot end soon enough. [Pic via]

What Did You Want To Accomplish When You Grew Up?

What Did You Want To Accomplish When You Grew Up?

The first in a series about youth.

When you’re a kid, there are no limits on the world — everything seems possible. When he was seven, my brother truly believed that one day he’d wake up to see a T-Rex peering at him through his bedroom. (Yes, he had just watched Jurassic Park.) He also talked about inventing a plane that could withstand the strength of a tornado enough to fly within its wind currents, for a real bird’s-eye view of the storm. To find out other would-be inventions and asked an assorted group of tech- and science-minded folks, “When you were young, what did you want to invent, discover or accomplish in the future?” Here’s what they said.

Sam Biddle, senior staff writer at Gizmodo

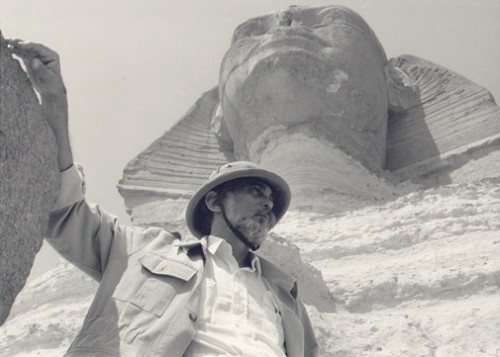

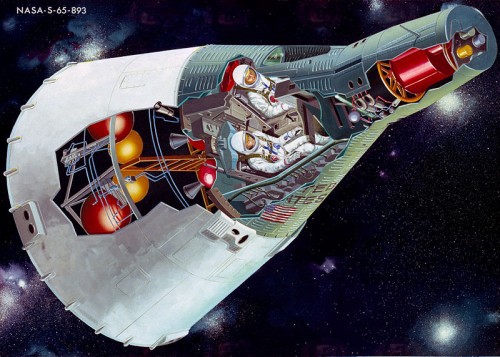

I never wanted to invent anything when I was little. Probably because my parents were writers, and that’s a silly and impossible thing to try to comprehend when you’re tiny. Like most little boys in a vaguely militarized society, I wanted to be an astronaut and be in rockets and discover planets, until my parents told me you had to be in the Air Force before you could be an astronaut. Is that even true? I never really followed up, since I was, like, five. My parents didn’t push me in any direction as I grew up, but didn’t want their tiny little guy having missiles fired at him, so it was vaguely discouraged. That was the end of the astronaut phase. Then I dreamt of being an undersea explorer, idolizing Robert Ballard and Jacques Cousteau, only to gather from my parents that pretty much everything underwater had been discovered already, especially the Titanic, which had the fuck discovered out of it already. After going to the British Museum when I was eight years old, being an Egyptologist seemed pretty neat, and it impressed dinner party guests when I said “Egyptologist,” but then my parents told me that all the stuff had been found in all the Pyramids and tombs, and that it probably wouldn’t be something anyone could do by the time I grew up. I think this is probably true, so thanks, Mom and Dad. By then I was starting to get really excited by books and reading, so I just figured I could somehow make money doing what my parents did, and gave up studying math and science and diverted all of my mental energy into Star Wars novels and writing dumb short stories about robots and museum heists and robot museums. But my parents are proud of me now as a non-child, so I’m mostly pleased too.

Rebecca Boyle, Popular Science contributor

When I was a kid I wanted to be an astronaut — Sally Ride, who passed away recently, was my personal heroine. In 1986, my haircut was pretty much exactly like hers. Thanks to her, it never occurred to me that it would be groundbreaking or uncommon for a woman to fly a space shuttle or study physics — it seemed eminently reasonable. I had an inflatable shuttle in my bedroom and I covered the walls with glow-in-the-dark stars arranged like constellations. I dreamed of going into space and discovering a comet, just like Halley’s Comet. I even tried to read Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, and kept a dictionary next to me so I could look up the biggest words.

When I was in sixth grade, my parents indulged this ambition by sending me to Space Camp, which was awesome despite the fact that I was mercilessly teased for my astronaut flight suit. Then I grew up to be a writer instead. Two weeks ago, I was at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory for the Curiosity landing, and it felt like coming full circle — I might not fly into space, but I can do it virtually. Although, you never know. If there’s ever a volunteer mission for humans to Mars, maybe I’ll sign up and blog about it.

Matt Buchanan, editor of Buzzfeed’s FWD blog

I like sleeping. I hate missing things. What that’s meant, forever, is that I often stay up until 4am or until dawn, and then I wind up sleeping to four in the afternoon. Less than ideal. I’ve gotten better about this since I’ve gotten older — ’’cause like, work — but it’s still one of the core dynamics in my life. So when I was younger I wanted to invent a method or device or like discover alien technology so that whenever I went to sleep, the whole world stopped cold. Paused. I even imagined a cool special effects sequence that would show what it was like — because I figure in those moments between being fully awake and fully asleep, or have a waking dream, that whole world would be tripping balls. Things would be slowing down and speeding up. No one would know but me, of course. But it’d mean I could sleep as much as I wanted, whenever I wanted, and I’d never miss a thing. What a luxury.

Clay Dillow, contributing writer at Popular Science

When I was a kid, my dad picked up this two-seater go-cart at a second-hand sale. My brother, sister, and I loved that thing, and we spent innumerable hours tearing around the place, as well as fixing flat tires and learning how to replace the perennially blown clutch. It was at some point during these years that I became fascinated with the idea of powered parachutes, or PPCs — those three-wheeled, dune-buggy-looking vehicles that fly suspended beneath a huge parachute. I remember desperately wanting to figure a way to hack that go-cart — with all five of its horsepower at my command — into a powered parachute of some kind. In essence, I wanted to invent my own personal flying machine. So in some respects, maybe I wanted to invent the flying car. But really I just wanted to shake myself loose from a two-axis, terrestrial existence and go skyward — an impulse that I feel is perfectly natural.

I also wanted to invent teleportation. Still do.

Cory Doctorow, writer and BoingBoing editor

Total, multilateral, global nuclear disarmament.

Kelly Faircloth, tech writer at Betabeat and The Observer

Ever since an all-too-early exposure to “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” I’ve been obsessed with faster-than-light travel. But it turns out I’m completely, utterly horrible at math, and therefore I realized pretty early on I would not be inventing FTL technology. So my abiding secret desire as a child was to discover some Stargate-style ancient alien relic with spacefaring technology that humanity could just rip off. Voilà! A shortcut to the stars.

Sadly, there were no extraterrestrial wrecks to be stumbled upon in Middle Georgia. (I checked.)

Ann Finkbeiner, writer and The Last Word on Nothing proprietor

If “young” is between 10 and 15: I lived on a small farm that didn’t distinguish between men’s work and women’s work, you just did what needed to be done. So though I was obsessed with books, feeding chickens or cleaning bathrooms or hoeing beans usually needed to be done — the upshot being that I read those books behind chairs where I wouldn’t be noticed. All this created in me a powerful laser-like yearning to get the hell out of Dodge and write books myself, books that would take the reader into rich and meaningful worlds that would make beautiful and orderly sense. I didn’t do that though.

John Green, writer

I wanted to be an earthworm scientist. I basically wanted to be this guy. That guy has my dream job. Later, by high school, I wanted to be a novelist, but I think I mostly just wanted to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. I remember when Toni Morrison won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and that seemed really fun and exciting.

Rebecca Greenfield, staff writer at The Atlantic Wire

As a child, I was concerned with the mundane: traffic and weather. Being late made me anxious, so when stuck in traffic jams, I dreamt up a genius invention called the flying car that, when stopped behind a long line of motionless cars, could fly above and beyond the traffic. (Different than an airplane! Because it could also drive on the road. And, was in the shape of my family’s minivan.) I understood that there were inherent complications with my invention. If everyone had flying cars, then there would be flying car traffic jams. (Point defeated.) And, in-flight accidents would probably be nastier than on the ground ones. But, I was more concerned with the end goal: A world without traffic, something that would make a lot of people — but especially me — happier and more on-time.

I also loved arguing about the weather, a skill that would lead to my eventual election as the first female president of the United States of America. Weather-related arguments involved convincing someone they were either wrong about the forecast or about the current ambient conditions. These arguments were easy to win because nobody wants to get into a deep conversation about what it’s like outside, unless they are a grandparent and grandparents always let their grandchildren win. These sparring talents meant I was destined to be a great lawyer, and, as we know, great lawyers get elected presidents of countries. I am not sure younger me knew what future me’s presidential platform would involve, but it probably had something to do with global warming — rising gas prices were another worry of mine. And, waste — I hated waste. Perhaps I should have gone the law school route because the climate is scarier than it was back then and the planet could probably use some of President Greenfield’s green policy proposals. (E.g. “Mom, why didn’t you take the reusable bags to Wegmans!”)

Fred Guterl, Scientific American executive editor

In nursery school I remember this one kid whom the “big kindergarten kids” made fun of. I recall they objected to his shoes for some reason. He and I started hanging out on the swings and the jungle gym together. I don’t remember when we started to get interested in space, but when we were a little older we became obsessed. It was the early 1960s, during the moon race, and NASA was launching Mercury and Gemini capsules, in the long slow crescendo to Apollos, which seemed hopelessly distant and futuristic. All my friend and I wanted to do and think about was try and get into orbit somehow. We would spend hours in the garage, building spaceships out of anything we could find lying around. We built one out of plywood and two-by-fours that was triangular, with a “control panel” of old screws and knobs, and we’d spend hours fiddling with them and practicing for the day we just knew would arrive when the ship would carry us aloft. A while later we use pointy wood screws to attach the two garbage to one another, and attached them in turn to the top of an old discarded boiler casing we had found in the woods. I climbed a ladder and crawled into the “capsule” on top. My friend lit the boiler. It didn’t take off. I remember yelling, “It’s getting hot!” Mission aborted. My friend kicked the whole apparatus over. I still have a scar from the landing — one of those sharp screws was sticking out. Eventually, my friend and I drifted apart, the space program went into remission, we got interested in adolescent things. It took many years for me to return to that early inspiration. Now I’m a science writer.

Eric Hand, reporter for Nature

I wanted to build a massive, livable, year-round treehouse.

Reyhan Harmanci, West Coast editor of Buzzfeed’s FWD blog

My mother quit her job when she had kids, and she was always very ambivalent about that choice. It made a big impression on me: When I was little, I didn’t have any particular calling but really craved some kind of professional success. I can remember learning about obituaries and my parents telling me that the highest honor was to have an obituary in The New York Times and then plowing through old Times newspapers, trying to figure out what kind of person was most likely to get this award. I came up with “businessman” which was handy, because at the time, my fourth-grade side hustle involved making and selling (non-ironically) friendship bracelets for $.50 each. But even as I cycled through numerous career paths (in my head) — artist, lawyer, fashion designer, novelist, horseback rider, potter, hair stylist, Supreme Court judge, presidential speech writer — that dream of being featured in a New York Times obituary persisted. It only occurred to me later that even if I did get that highest of honors, how would I know?

Thomas Hayden, science journalism lecturer at Stanford

When I was a preschooler, I just wanted to be a cowboy or a firefighter. I managed to do a little bit of both of those along the way, but by the time I was about 14, what I wanted to invent more than anything were machines powered by the heat of a well-turned compost heap. I experimented for years, trying to maximize heat production and energy capture, and eventually managed to power a small steam engine with compost heat, using petroleum ether rather than water. I subsequently studied microbial ecology in university to push my efforts further but then, tragically, became distracted by writing and threw my life away on science journalism. Imagine if Tesla had been similarly seduced by the high glamor of the written word? Devastating!

John Herrman, deputy tech editor at Buzzfeed

I had a pretty short dream-span as a kid. I also had the unfortunate, but I think common habit of interpreting small approvals as, like, cosmic endorsements — a good grade or a nice comment or just any little success was a sign that I could eventually master some new thing, no problem. (Q: What makes a millennial a Millennial? A: A conflation of ability and actual accomplishment combined with a gross overestimation of ability.) There was an author phase (I was going to write the next Hardy Boys), a scientist (paleontologist) phase, a doctor phase. Lots of short phases, followed by a healthy and complete teenage collapse of confidence.

Last time I was asked this question was when my middle-school class was assembling a 20-year time capsule. My note to myself had a dollar attached, to go toward a beer with my two best friends at the time, and a pencil-scrawled insult: “Are you seriously not married yet?”

Sarah Kessler, associate editor at Fast Company

When I was seven, my parents told me that I could have a pony… if I bought it myself.

At the time, I didn’t realize this actually meant no, so I enlisted my neighborhood accomplice, and we set to work dividing our allowance into mason jars labeled “horse,” “horse food” and “barn.”

It turned out that financing a horse cost more than our combined $15 of life savings. And as a pair of seven-year-olds, our employment opportunities were limited. Thus we were forced into entrepreneurship. We made friendship bracelets to hawk at the local beach, set up a lemonade stand on our rarely trafficked rural road and attempted to sell our younger brothers into manual labor.

I’d like to say this scheme was the first sign of budding business prowess. After all, we did make, like, 20 bucks. But I think it was much more indicative of how much I wanted a freaking pony.

Maggie Koerth-Baker, science editor of BoingBoing

I was about 5 or 6 when I first came up with an answer for the question, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” My early career goal: Become a ballet-dancing archaeologist who was also President of the United States. Apparently, I expected to be much better at time management than I actually am.

Matt Langer, Awl contributor and New York Times developer

I always wanted the future to look the way it did in William Gibson and Bruce Sterling novels. Like it did in Blade Runner, more or less: dystopic but strangely enough still kind of alluring, this hypertechnologized world where it just rains all the time and the sun never comes out because the atmosphere’s been pumped so full of gases (ha, which shows how neurotic we are, really, considering that back in the ’80s our collective awareness of these things was pretty much limited to a fuzzy understanding of the term “chlorofluorocarbons” and a gnawing worry about using too much hair spray). But the (ugh, for lack of a better word obviously) cyberpunk world those guys portrayed not only seemed totally plausible (if not even a little bit inevitable) but it also gave something of a silver lining to the notion of a dystopia, at least inasmuch as sure, yes, we couldn’t see the sun, but look at us we were still conquering this miserable world with our TECHNOLOGY! And so in any event this was all very appealing to young nerdy me, the thought that I could grow up to live in a city illuminated only by neon lighting and blinkering LEDs, where people ducked into noodle bars to get out of the rain and ate alone while chefs bantered away behind the counter in foreign languages. There was even an old video game that did this world very well, a game called Privateer (part of the Wing Commander franchise for those who remember the days when video games used to come on forty-odd 3.5″ floppies), and one of the missions in that game took you to a city that perfectly captured this future: lots of rain and dark alleyways, severe concrete architecture, light sources that always flickered, etc. Looking back I realize the aesthetic was probably just “Tokyo in shitty weather,” but whatever, it felt exotic. Anyway, turns out all these sci-fi writers were only right about the greenhouse gas half of their dystopian futures because we’ll all actually just be dying in fires and floods pretty soon here — but it was fun to pretend while we could!

Tom McGeveran, co-editor of Capital New York

I figured out pretty early on that I wanted to be a philosophy professor — somewhere around sophomore year of high school. This seemed both a safe (ha!) and fulfilling (perhaps ha?) idea at the time, and it stayed with me for about seven or eight years.

I was going to go get a PhD in philosophy, and figure out some way of turning all of the stuff in common among followers of Derrida and his ilk, and Catholic theologians, and Talmudic scholars, into some kind of not-crazy, distinctly American moral philosophy that would matter, on the scale of John Rawls, but across metaphysics and epistemology and not just politics or ethics or law. I felt, in a way that seems adolescent in retrospect, probably because it was, like I alone realized they were speaking the same language and that our cause was against analytic and Anglo-American philosophy, which was doing lots of great stuff on its own but was much in danger of removing the most important questions of philosophy from the agenda.

I hadn’t quite figured it out yet — I thought the answers lay somewhere in the nexus you could find Thomas Merton, Gershom Scholem, and Derrida all crossing, and I was starting to think of Emmanuel Levinas as a weird lodestone.

I wasn’t serious enough not to want to fuck around after college a bit (where I took really only philosophy, language and history classes, and as few required courses as possible), as everyone did in the mid-90s, but I was pretty sure my fate was there waiting for me, as an inevitability.

But I had a rude awakening when I was accepted to zero philosophy PhD programs (apparently 23 year old white men who would like to simply try, again, to explain how absolutely everything works with a simple theory were not yet in vogue), and when I started hearing the stories of academics a few years older than me who were trying to get on. They all kind of high-fived each other when one of them got an appointment to a rural community college post in Alberta.

After my post-college rumspringa from academics, in which I switched low-paying temp and administrative jobs every couple months to keep being able to go out to gay bars, downtown performance art events and poetry readings, I realized I would never unlock that philosophical-diplomatic secret, never really figure any of that out, and that I would never be a world-changing poet or philosopher or priest. It was weirdly comforting: I was finally able to get down to work. And, I loved New York too much to ever consider leaving it.

Michelle Nijhuis, Smithsonian contributing writer

A few years ago, my alma mater sent me a copy of the application essay I wrote in 1990. (It was typed. With a typewriter, kids.) I cringed and put the envelope in a file. Now that The Awl has given me a reason to finally read it, I’ll risk humiliating my 17-year-old self — I can just hear the poor girl rolling her eyes — with an excerpt.

Once I thought that I wanted to be Something. I saw Something as a mystical title, indefinite but recognized by all: she is Something, isn’t he Something, wow aren’t they Something.

I did not know that in order to be Something, one must “exhibit leadership potential” but never realize that potential until the proper time. One must belong to many organizations and stand for many causes, but never weep or scream or take a radical stance on behalf of anyone in particular. One must always use a soft lead pencil, fill in the circle completely, and make the mark dark.

I didn’t realize that if you’re going to be Something, you certainly can’t walk up any waterfalls or sound any barbaric yawps (although you may read selected works of Walt Whitman. Selected mind you) or haunt any dusty bookshops or travel to any exotic foreign countries except for business purposes. You can’t drink fewer than eight glasses of water each day, and you can’t let someone lean on your shoulder without expecting something back. You can’t laugh at the world as you try to save it, and you can’t sing in the shower. And I keep telling you that there will be none of that kite flying while you’re on the way to being Something.

When I discovered all of this, I thought, well, isn’t that something. And being Something wasn’t very attractive any more, for suddenly I could be anything.

David Quammen, writer

When I was a boy I thought I wanted to be 1) a herpetologist, or 2) an entomologist, or 3) a writer. Slightly later, I focused on writing, and thought for a while the ideal career path would be writing satiric songs or else novels. Then I rediscovered the natural world, discovered science, discovered nonfiction.

Jessica Roy, tech reporter for the Observer and Betabeat

My favorite book as a kid was Mandy by Julie Andrews Edwards, a novel about an orphaned girl who climbs over the wall behind her orphanage and discovers this little cottage that she fixes up and turns into her own hideaway. I dreamed constantly of growing up and finding my own abandoned place like that where I could sit and read and be alone. I once found a pile of boards stacked against a tree in a wooded area near my house, but it turned out to be a homeless man’s squatting zone, so that didn’t turn out so well. I also used to scale this weeping willow tree by my elementary school and settle into the branches to read and pretend it was a secret place, but one day the school district decided to cut it down. A group of men arrived wielding tree cutting equipment and my fourth-grade teacher let me and a friend leave class so that we could go over and try to stop them from chopping down our favorite tree. The men just laughed at us. I stole a piece of bark from the doomed tree, which is probably still buried among love notes and paper fortune tellers in a box in my dad’s garage. I settled for building blanket forts and dreaming about publishing a novel “by age 25” in my bedroom after that.

Matt Soniak, Mental Floss blogger

1. I wanted to invent a machine that would efficiently squeeze toothpaste out of the tube for me, and not leave any little bits behind.

2. I was obsessed, around the age of eight or nine, with the idea of discovering a stable, hidden population of animals outside their native range. For a little while I was sure I had evidence of a group of marmosets living on the streets of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

3. I wanted to touch a boob.

I was an ambitious kid, I guess. I have since accomplished at least one of these things.

Clive Thompson, Wired columnist

I’m 43, so I started playing video games with Pong and Space Invaders. I spent a ridiculous amount of time in the arcades of Toronto, and I desperately wanted to make my own video games.

I figured if I had my own computer, I could have taught myself. But my parents, while totally middle class and able to buy one, wouldn’t. My mother argued I’d just use it to “waste time playing games.” She didn’t realize that playing games is a conduit to thinking about games and, for me anyway, learning how to program well enough that I could make my own. (Though she wasn’t entirely wrong either; I’d probably have blown a lot of schoolwork playing games.) I knew a bit of programming back then but not enough to make good games.

So I put my game-designing desires on the backburner and worked instead on my other big desire, which was to be a journalist. Luckily, that one worked out!

The great thing is that in the intervening years, learning programming has become easier and easier. I’ve always done bits of programming here and there, mostly so that I know, intellectually, what a language is capable of. But I never bothered to learn so much that I could make games. Now, however, there are a bunch of languages that are amazingly well suited to making interactive games, like Processing, or pieces of hardware for making interactive physical games, like the Arduino.

My six-year-old son recently asked me, in a hilarious generational echo, ‘Hey, how could we make our own video game?’ So I downloaded MIT’s free Scratch programming language, which is custom-designed for letting kids design games, and together we’ve designed a couple of games in the last few months. It is, as I’d suspected, a blast playing a game that you yourself have created.

In a way, I’m glad I never became a game designer, because — having met game designers, and gotten a glimpse beneath the hood — I doubt I’d be very good at it. It requires a type of devotion, creativity, and attention to detail that I do not really possess. But I’m glad that programming language for DIY game-making has become simple enough that one can now dabble in it. It’s a great hobby!

Nitasha Tiku, staff writer for the Observer and Betabeat

I was never one of those kids who took things apart just to put them back together, which is probably a leading indicator for becoming an inventor or builder (of physical things, code, etc.). Much like hurting animals → serial killing. A friend once showed me the wire-y insides of a radio he’d pried open in his basement and I was like, Oh, so that’s how you figure out how things work. And not, as I did, by reading the book The Way Things Work, then promptly forgetting where lightning came from.

I wanted to discover excuses to stay indoors and read. Like rain or minor apocalypses. After my brother and I watched Defending Your Life (Albert Brooks, Meryl Streep, set in limbo) I worried there might be cameras secretly taping you everywhere, so I’d check around for them, especially in other peoples’ bathrooms. Does that count as a “discovery”? Pretty sure I wanted to be good at everything and very special, eventually.

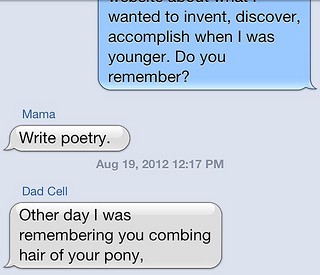

I tend to remember things very precisely or not at all, so I asked my parents.

He’s talking about my My Little Pony, which reminds me — I wanted someone to invent something that tasted as good as that plastic smelled.

Natasha Vargas-Cooper, writer

Phillip Larkin invented sex in 1963. Masturbation was created twenty-five years later when I discovered it’s basic formula. During that period of time, I wanted nothing more than to invent a cure for masturbation, a painless antidote. My mission was partly successful by 1989 when I (finally) threw away my mother’s tattered and sodden copy of The Joy of Sex book I kept under my bed.

David Wagner, writer for The Atlantic Wire

It probably isn’t hip to admit that you were ever devoutly religious, but when my kindergarten teacher asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I confidently answered, “a pope.” That’s right. Not the pope. A pope. I thought they were as common as firefighters and astronauts. Imagine my surprise when I found out that only one dude at a time got to ride around in the Popemobile.

I come from the kind of Catholic family that goes above and beyond attending mass every Sunday (people who don’t observe holy days of obligation aren’t real Catholics, after all). First holy communion, confession, confirmation — I went through the whole sacramental suite. I even did time as an altar boy and played in the church praise band (I know bragging is a sin, but man could I lift the Lord’s name on high). Other families teach kids to revere the President, or brain surgeons, or maybe engineers. But where I come from, no earthly mortal is more important than the head of the Roman Catholic Church.

I wasn’t all that disappointed to learn that my papal aspirations were highly unrealistic, just surprised. I guess it was the first time I realized that “you can accomplish anything you set your mind to” is more of a pat on the head than a true statement. I began cycling through other career choices. Those guys who flip signs at intersections, pointing drivers toward the furniture outlet, seemed pretty cool for a while. After seeing Jurassic Park, I pictured myself as an intrepid paleontologist. Later, I thought seriously about becoming that jazzy dude in Nordstrom who tinkles away at the piano. If someone would’ve told me that I’d grow up to write for the Internet, I would’ve said, “How can somebody write for Yahooligans?”

Now that I’m what you might call a lapsed Catholic, I look back on my younger self and chuckle. But after I get through chuckling, some wistfulness sets in. I no longer have any desire to be a pope, but I do sometimes wish my head were still filled with such innocent, naive dreams.

John Wenz, writer

I became an iffy believer in the concept of God sometime around when I was 13. And I was in Catholic school at the same time, which put me in a weird, weird place. After being told the concept of God and Heaven for so long, suddenly the most terrifying thought to me was the concept that of consciousness ending and that being it when I die. So of course my iffy understanding of science led me to the ultimate idea for an invention I couldn’t possibly implement: I wanted either a robotic body I could put my brain into and live forever, or I wanted to entirely digitize my brain and be able to live as a sentient computer program, like a really boring version of The Matrix entirely design to allay my fear of death. Some of the details of the robotic body have changed — I no longer need it to withstand the vacuum of space — I’m not entirely sure I’ve given up on this dream.

Related: What Books Make You Cringe To Remember?

Nadia Chaudhury wanted to somehow create the ability to stop time like the girl from Out of This World. She still wants it. Top photo and Gemini capsule illustration courtesy of NASA; photo of powered parachute by Derek Jensen; pony photo by Steve Lodefink; Popemobile photo by Broc.

IDF Bulldozer Officially Accidentally Runs Over Person Twice

The death of Rachel Corrie — who was bulldozed while trying to prevent a house demolition in Palestine, atop a pile of dirt and wearing an fluorescent orange vest — has been ruled an accident in court in Israel.

Would You Like 'New York Times' Platinum Executive Status? (Yearly Joe Nocera Lapdance)

This “brainstorming about what the Times should do” is largely accurate. People love membership, when it doesn’t suck. The idea is to go more MoMA or BAM and less NPR. Look at the BAM Cinema Club membership levels, which are (sorry!) better executed than MoMA’s. But also, then look at airline frequent flyer programs. People love belonging. But more than they love belonging, they love having status. Scratch even the most socially liberal person and you’ll still find a person that loves convenience, if not outright status snobbery. (Just speaking from personal experience!) (Photo credit.)