Labor Day Weekend, 2012

Let’s stay in town and do nothing! Or also: roasted pigs! Diplo! Goldfinger! Juan Martin Del Potro! Salt n Pepa!

A Flank Steak For The End of Summer

by John Ore

A series on things to make, eat and imbibe this summer.

The almanac says we’ve got a few weeks left of summer. But if you’re like me, Labor Day is the bookend that marks summer’s close and the beginning of all things fall — that pivot point when the the state fair shuts down and college football starts up. While I can’t get my head around summer ending just yet, I love the transition to fall, when grilling moves from the backyard to the tailgate. If you’re planning one final blowout of the summer in observance of our favorite socialist holiday, don’t bore your guests with burgers and dogs. Instead, serve this ambitious-but-worth-it meal that encompasses the heat, sweetness and spice of the Southwest. Warning: lots of cilantro below.

Main: Marinated Flank Steak

Sides: Cornbread Salad and Heirloom Tomatoes

Booze: Mexican beer or Spanish wine

MARINATED FLANK STEAK

I always get my hanger, skirt, and flank steaks mixed up, so have to do a quick mental review every time I hit that section of the butcher’s case. Hanger and skirt steak are known as “the butcher’s cuts,” because, as this article helpfully points out, “there was never enough of either cut to display, butchers would take them home for family meals.” Flank is often left to fajitas. I like grilling all three of them because they’re easy to prepare, require only a couple of minutes a side over high heat, and they serve you and your guests communally.

However, unlike the rest of my summer favorites, this recipe goes the marinade route instead of the dry rub route. I adapted these recipes from The Thrill of the Grill, published in 1990, a dog-eared and stained copy of which occupies a central place in our cookbook library. Ingredients and prep are usually customized based on the availability of seasonal ingredients and in the tradition of my father, who never wrote anything down.

Now, a marinade might seem a little high-maintenance, but you can prep a lot of the ingredients ahead of time, and the leftovers from this recipe are perfect for tailgating. You’ve got a long winter to look forward to, so let’s draw this out as much as we can.

2–3 lb. flank steak

Flank may not be the most tender of the hanger-skirt-flank troika, but it’s got a ton of flavor. Marinating helps tenderize as well as add some zing to it, while the BBQ sauce is smoky, spicy and sweet.

Marinade

1 can chipotle chiles, chopped

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 tbsp cilantro, chopped

4 tbsp olive oil

10 tbsp lime juice (say, 5 limes or so)

Coarsely chop the chipotle peppers, sauce and all, and mix with the rest of the ingredients in a large, shallow baking pan. Thoroughly coat the flank steak, cover, and marinate in the refrigerator for about 5 hours, turning occasionally. We’re not going for ceviche here, so don’t marinate to the point that the acid in the lime juice actually starts cooking the steak. The grill will start to get jealous.

BBQ Sauce

¼ cup honey

2 tbsp peanut oil

canned chipotle chiles

2 tbsp balsamic vinegar

2 tbsp brown mustard

8 tbsp lime juice (say, 4 limes)

2 garlic cloves

1 tsp cumin

2 tbsp cilantro, chopped

1 tsp salt

freshly ground black pepper to taste

serves 4

I’m not really into BBQ sauces, but sweet-and-sour combinations, like this one (and this one), are tremendous. Homemade sauces are kind of a pain in the ass to make, but so much more more rewarding. Combine all of the ingredients, save the cilantro, salt and pepper, and puree in a blender or food processor. You can adjust the heat in this sauce with the amount of chipotle peppers you add. I like a little bite that doesn’t overwhelm, so three are probably just right, but feel free to step it up to suit your asbestos tongue and alimentary canal. Add the cilantro, salt and pepper and serve in something festive like a gravy boat.

Prepare a hot fire in the grill, we’ll be using direct heat for this one. Remove the steak from the marinade, salt and pepper to taste, and cook over high heat for about 5 minutes a side. You’re aiming for a nice char on the outside, so don’t be afraid to let the flames caress each side. Let the meat rest for 5–10 minutes before carving. As with hanger and skirt steaks, you’ll want to cut against the grain at a decent angle using a very sharp knife for very thin slices. Ladle the sauce over the slices as you serve them, or be the guy that dips them directly in the gravy boat.

CORNBREAD SALAD

3 cups cornbread, crumbled

1/2 red bell pepper, diced

1/2 green bell pepper, diced

1/2 red onion, chopped

4 tablespoons parsley, chopped

2 tablespoons cilantro, chopped

2 green onions, chopped

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 jalapeno pepper, chopped

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

3 tablespoons olive oil

1 tablespoon white vinegar

6 tablespoons lime juice

serves 4–6

This Southwestern take on a panzanella uses cornbread and lots of peppers. Feel free to make homemade cornbread for this one (ooooh, la-di-da!), but don’t be ashamed to go to the bullpen and get some nice store-bought stuff. I mean, look at the list of ingredients up there. You’ve got a lot on your plate already.

However you end up with it, crumble the cornbread coarsely and spread evenly on a cookie sheet. Bake at 250 for about 90 minutes, tossing every 30 minutes, until it is dry and nice and crunchy, like granola.

Combine the veggie ingredients in a large serving bowl, add the cornbread, and toss to mix everything up. In a small bowl, whisk the oil, vinegar and lime juice into a dressing, then add to the cornbread salad and toss to coat evenly. Fresh corn straight from the cob or similar complementary ingredients also work well in this salad, so go nuts.

Serve everything with sliced heirloom tomatoes drizzled with olive oil and a little salt.

BOOZE

There’s a lot going on in this menu, and a lot of spice that’s going to just bulldoze right through drinks with subtle or delicate flavors. With that much cilantro, chipotle and garlic, a nice Mexican beer provides a neutral, seasonal and refreshing accompaniment that can help cut the heat of the food. Since I’m not that interesting of a guy, I prefer Pacifico

out of the bottle. Hey beer snobs: the limes are in the food, and at least I didn’t say Corona.

Staying with the theme, full-bodied, spicier Spanish reds like Riojas and Priorats stand a fighting chance against the bold flavors in the marinade, BBQ sauce, and cornbread salad. Priorat can be on the pricier side of the spectrum, but Alvaro Palacios makes an excellent one for around $20, as does Onix. Might as well start getting that palate back onto reds.

Previously in Hot For Summer: T-Bone, For Two and How To Make Beer Ice Cream

If it’s not snowin’, John Ore is grillin’.

New York City, August 29, 2012

★★★★★ The blue. The blue! There it was: a pure color field, simultaneously flat and as deep as the universe. Massed leaves in the treetops on Chrystie Street, stolidly lit and shaded and dimensional, stood against the flawless immateriality of it. Perspective faltered; the stairway going upward lost its way and pivoted into Escher space. Later there would be a few tiny flecks of stupid, stupid clouds, intrusions on the empty dome. Ridiculous.

The British Invasion... Again: After The Battle

The British Invasion… Again: After The Battle

by Robert Sullivan

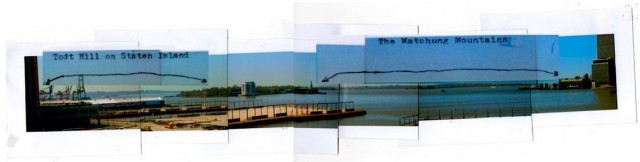

The final installment in a seven-day series exploring how the trail of the Battle of Brooklyn would pass across modern-day New York. Shown in photo, the Watchung Mountains.

It’s over. The Battle of Brooklyn is done, or at least it was on this day 236 years ago, with the Americans momentarily out of reach of the British, having evacuated to the island of Manhattan.

The British were shocked. “In the Morning, to our great Astonishment, found they had Evacuated all their Works on Brookland and Red Hook, without a Shot being fired at them,” a soldier wrote. Earl Percy wrote to his father, the Duke of Northumberland, from Newtown, a village in Queens, which the British now controlled, saying a British victory was at hand. “They feel severely the Blow on the 27th & I think I may venture to assert, that they wilt never again stand before us In the Field. Every Thing seems to be over with Them, & I flatter myself now that this Campaign will put a total End to the War.”

On the other side of the East River, a minister in Manhattan watched the Americans came ashore, out of breath, bedraggled, their spirits transformed, after only the first battle of what would be a long war.

He wrote in his diary:

In the morning, unexpectedly and to the surprize of the city, it was found that all that could come back was come back; and that they had abandoned Long Island. … [I]t was a surprising change, the merry tones on drums and fifes had ceased, and they were hardly heard for a couple of days. It seemed a general damp had spread; and the sight of the scattered people up and down the streets was indeed moving. Many looked sickly, emaciated, cast down, &c;,; the wet clothes, tents, — as many as they had brought away, — and other things, were lying about before the houses and in the streets to-day; in general everything seemed to be in confusion. Many, as it is reported for certain, went away to their respective homes. The loss in killed and wounded and taken has been great, and more so than it ever will be known. Several were drowned and lost their lives in passing a creek to save themselves. The Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland people lost the most; the New England people, &c;,. it seems are hut poor soldiers, they soon took to their heals.

The invasion of Manhattan was imminent. Washington was not feeling good about it. He wrote to the president of Congress: “… with the deepest concern I am obliged to confess my want of confidence with the generality of the troops…” By the end of the war, his feelings would change, but right now, he despised the militias.

After the Battle of Brooklyn, there was another end-of-summer rainstorm, lightning killing American soldiers in camp. And then fighting begins in Manhattan, British troops landing at Kips Bay, on September 15, just below what is today the U.N. There will be a battle in what is today Central Park, where the British, thinking they’re winning, use a fox hunting call (indicating that the fox was about to be caught) to insult Washington, and Washington, a fox hunter recognizes it, after which the British lose. A friend of mine spent a year or so walking and looking around before he could see the outline of the valley in which this battle took place, in and around McGowan’s Pass, but now he swears he can see it. Eventually, George Washington moved his headquarters to the Bronx, at the Morris mansion, Washington Heights, a house Bob Vila once visited, on a campaign through the area.

As fall came, action went up in to Westchester — the Battle of White Plains — and then back into upper Manhattan, near Mount Washington (the mount was already named for Washington in 1776). At last, the British pushed the Americans out of Manhattan, at which point the American fled Fort Lee, raced down through Hackensack, burning bridges behind them. They crossed the Meadowlands, and then got to the Delaware, which they also crossed, General Glover once again taking all the boats from the British side and carrying them over to the American side, in case.

And so we are poised, by Christmas, for the Crossing of the Delaware, and then, 176 years later, for the first reenactment of the Crossing of the Delaware, begun by a theater impresario, history buff and inventor of the Smellodrama, St. John Terrell. The crossing is reenacted every year, as it is in this video, in which Washington is played by a local police officer. (I saw this particular Washington play once, though “play” does not seem like the right word as the reenactors refer to themselves as “living historians.”)

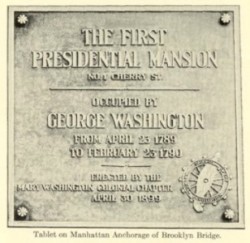

After crossing the Delaware, Washington will bring his troops back within striking distance of New York City — oh, how he wants to take the city back, even though his allies, chief among them the French, really don’t think he should bother. When he comes back into town, he rides his white horse down Broadway — that’s the kind of guy he is — and a year later, sets up in the first White House, on Cherry Street, now beneath the Brooklyn Bridge. There used to be a plaque but I can’t find it anymore.

The key to the winning of the war, from a geologic standpoint, is the Watchung Mountains, pictured at the very top. I don’t want to go too deeply into it here; you could read a book about it. But I will say that you might not have ever noticed them before; that they are mountains even though you don’t think they are and that geologists who study the history of American warfare see them as more than significant, especially since Washington set up camp behind them, in Morristown, New Jersey. “Washington’s choice of winter quarters at Morristown behind those natural redouts was a stroke of genius,” wrote the geologist Bradford Willard in a 1963 essay entitled “Geology and Wars: A Neglected Factor in Wars Within the Continental Limits of the United States of America.”

Something that bothered Washington throughout the war was the presence of the prison ships that the British kept in the East River, filled with Americans that the British had taken prisoner. The people on the ships became known as the Prison Ship Martyrs after the revolution; all told, an estimated 11,000 men and women were left to die on the British prison ships in Wallabout Bay, the cove off today’s Brooklyn Navy Yard. The first prisoners put on the prison ships were the survivors of the Battle of Brooklyn, and after that various prisoners from all over, as well as, presumably, citizens who refused to take a loyalty oath. More people died on the prison ships than died in all the battles of the entire Revolutionary War.

If you were an officer, or had any economic wherewithal you could buy your way off the prison ships. If not, you died there. Many are thought to have been black slaves who fought on the American side (even though the British offered them their freedom if they fought for the British side); others were average soldiers, as well as sailors taken off privateers. In the early 1800s, when businessmen raised money to build the statue of George Washington that now stands on Wall Street, Tammany Hall asked why there wasn’t a monument to the Prison Ship Martyrs, as the bones were still washing up on the shores of Brooklyn for many decades after the war.

Today the bones are interred at Fort Greene Park in a crypt, beneath the beacon-like obelisk designed by Stanford White, put in place after Walt Whitman began a campaign for a monument. Every year, there is a ceremony there, commemorating them. I have read recently that there also will be a beacon on the top of the new World Trade Center tower. It is the part of the building that will bring it to a height of 1,776 feet. On September 11th, 2001, people in the area of Fort Greene Park went to the top of the park to watch the old World Trade Center towers as they burned and eventually collapsed. It seems to me that some places are always important to us. We go to certain points in our home landscapes over and over, to help us strategize, to find protection, to try to find a way to understand.

Previously: The Landing In New York, Scouting Old Locations, The General And The Moose, The Battle Begins, The Mystery Of The Missing Marylanders’ Graves and The Amazing Evacuation

Robert Sullivan is the author of a several books, including Rats, How Not To Get Rich, and The Meadowlands. His newest book My American Revolution will be published Sept. 4 (next Tuesday!) and is available for preorder.

A Poem By Bob Hicok

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

The ongoing

Do you know Bertolt Brecht’s The Hammer Throwers?

One hundred men divide on right and left sides

of a stage and throw hammers at each other

for half an hour. Every performance, a different number

of men are standing at the end, twenty nine

or three, and in one performance, the most famous,

one hundred and one men took a bow. Bertolt Brecht

was alone in noticing that his play

had given birth to a man. When asked his name,

the man replied, I am Bertolt Brecht.

But I am Bertolt Brecht, Bertolt Brecht

said to Bertolt Brecht, who responded, then we

are Bertolt Brecht. According to Bertolt Brecht’s

last diary, Bertolt Brecht survived

two more performances, until a splendid flurry

of accuracy hammered the cast down

to a single man. That man ran home

and told his wife, this evening, I was the star

of the show. She looked in his face

for the night sky, and told him that loving him

was a decision like breathing. She had never said anything

like that before and never said anything

like that again. She returned to knitting

the red scarf she’d been knitting since they were wed,

it ran out the door, where it was joined by the other

red scarves so busy existing. The man touched

where a hammer had grazed his temple, it felt warm,

like sleep feels right before sleep

and right after sleep, when he sometimes wonders

if he’s remembering or dreaming. Yes, his wife said

the one time he asked if he was remembering

or dreaming, yes you are.

Bob Hicok is.

Looking to get your poetry on for the long weekend ahead? Stop by The Poetry Section’s archives and tell ’em we sent you. They’ll treat you real nice. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

The Toothless Apparatus That Investigates NYC's Cops

What’s it like working for the Civilian Complaint Review Board of New York City, which investigates complaints against the NYPD? Not so fulfilling, it turns out, as one of its investigators confesses.

I often saw a deliberate short-circuiting of investigations, “fast-tracking” cases, or exonerating them without statements from all or even any of the officers involved. Often the rationale was that officers would likely repeat information conveyed by other officers in testimony or reports — essentially granting the police a presumption of consistency that fundamentally undercuts the CCRB’s ostensible neutrality, given that inconsistent witness testimony undermines the case of complainants. After I became a supervisor, the agency’s fundamental problem came into clearer view for me: The large majority of decisions made within the CCRB, by investigators and supervisors alike, were driven not by the goal of conducting full and fair investigations but by the desire to avoid more work.

Drink Hard, Exercise Hard

“Of all individuals who exercise vigorously, heavy drinkers tend to exercise the hardest. University of Miami Researchers evaluated the self-reports of 230,000 people nationwide regarding their weekly exercise and drinking habits. Of those who reported participating in vigorous exercise, men and women who were considered heavy drinkers worked out 10 minutes more than moderate drinkers, and 20 minutes more than non-drinkers.”

— Um, good for those guys, I guess. Personally I think my dedication to drinking is so intense that it precludes any efforts at exercise, but, you know, to each her own. (But listen: YOU ARE GOING TO DIE ANYWAY. Skip the workout and have another. We end up in the same ground, and this way is more fun.)

We're All Gonna Fry

Somewhere at the heart of my Venn diagram delineating the concurrence of disgust and desire you’ll find at least four of these items. Coronary City, here I come!

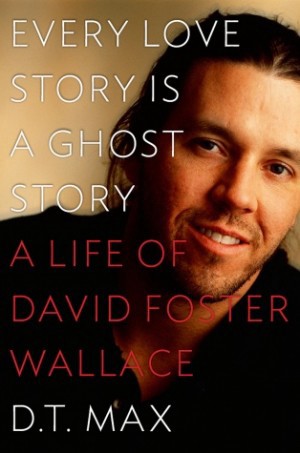

A Conversation With D.T. Max About His New David Foster Wallace Biography

A Conversation With D.T. Max About His New David Foster Wallace Biography

by Michelle Dean

In 2009, D.T. Max published a long piece about David Foster Wallace, and his suicide, in The New Yorker. The project grew into the biography Every Love Story is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace. In the final months of the book’s completion, through a stroke of incredible luck, I had the opportunity to help Max as a research assistant. Biography, it turns out, is complicated, wrenching work, particularly when your subject inspires the kind of devotion Wallace can, and where the end of a life comes in the form his did. With the book’s release today, I wanted to talk to Max about the process that went into its research and writing. Granted, it’s a strange thing to be interviewed by someone with whom you’ve worked for several months already — but he was willing, and over the past few days, we had this exchange by email.

Michelle Dean: The act of biography is obviously an enormous commitment to another person’s life, whether the terms are temporal or emotional or just sheer intellectual stamina. How did you end up undertaking that commitment here?

D.T. Max: I had no idea how hard biography was, especially a first biography of someone. I’d never done one before. I guess I just thought you asked people where someone was and what they were doing and you stuck it on note-cards, then you strung the parts together, à la Richard Ellmann. Definitely not the case, at least not with David. The first step was just the beginning of a very long slippery process. But, then, think about auto-biography? Do you remember where you were in May 1989? Or June 2001? And if you don’t care enough about yourself to remember that, why would anyone else? You don’t have to be a writer to have this experience, one that for me really reads as challenge, the ultimate challenge before the writer. How do I prevent you from disappearing into the past? Slipping into oblivion? Growing ghostly?

Right, but often biographers get misty-eyed in retrospect about how the subject “chose them” or what-have-you. Did you come to feel that way at all? I mean, it’s obvious that the biography was an outgrowth of the 2009 New Yorker essay you wrote, but beyond that.

The New Yorker piece was 10,000 words long and I’m sure it felt like an eternity to most writers and readers of magazine articles, but I felt I had elided over the problems, not gone deep enough. It seemed to me that there was a lot of unprocessed information in it. When I was done most of David’s life was only a little less spectral than when I began. I felt, for instance, I did a particularly cursory job on what would later turn out to be a fascinating time, Arizona, where he wrote Girl with Curious Hair. I just didn’t understand that time at all.

I felt a calling to do this, you know, and it was a calling that grew.

From outside too, I imagine?

There was this communal grief over David’s death that at least for me was eye-opening: the posts from people comparing his death to that of John Lennon, people speaking about the world as a scarier place without him. It started just after he died and kept growing and growing. It’s still growing.

Look, David was special and the purity of his commitment to his readers and his interest in their well-being was seductive — I saw this more and more and kept thinking about a more ample way to respond to this as a writer — that insistence that what he wanted to do was show what it was to be a “fucking human being.” If he wanted to show what it was to be a fucking human being, could I return the compliment?

But, you know, his is a terribly sad story too and if anything led me to hesitate it was that sadness. I took an oath at the beginning to make the book happier than the article, to catch the joy that kept breaking through. I don’t know if I succeeded.

It’s odd. As this project progressed, and the further I got into research, the more surprised I felt at all the trouble in his life. On some level, the cliché goes, it was all in those books, it was all there, but those books are joyful, too.

David lived his life mostly indoors and in his head. He starts out a boy in central Illinois, goes to Amherst College, does his graduate work at the University of Arizona, teaches briefly back at Amherst and Arizona, then home to eastern Illinois, becomes a graduate student at Harvard, enters a halfway house, winds up in Syracuse, back to Illinois to teach and then finally Pomona College near Los Angeles, to the end we all know.

But there are things that haunt me that got left out and phrases that bounce around in my head. One was about David and his dogs. I thought a lot about why he had usually two oversized, undertrained dogs tearing up his living room and scaring anyone who came to the door.

Maybe because he was so anxious he also had one of the most routinized lives you can imagine. He eats the same breakfast, goes to the same twelve-step meeting, works out with the same weights day after day. Yet in these humdrum stats — little different from those of any academic gypsy — is an immensity of feeling, living, and a great deal of suffering. The breakdowns, the suicide attempts, the triumph of Infinite Jest. How do you write about such a narrow but intensely lived life? How do you reveal the multitudes contained in the little rooms in which he lived? For a biographer it’s a challenge. When you get to the tradecraft of writing there are always strange allurements, inducements that would make most people shrug and say, why did that interest him? Among other things I wanted to capture the life of a late 20th-century middle-class American of my own age with roughly my own interests. We were both into Alanis Morissette at the same time though only he had a poster of her on his wall.

And in biography, you can use either a wide net or a narrow one. The dilemma was often how much you wanted to include. Too much and these things can become a kitchen sink (particularly when your subject wrote an 1100-page book himself); too little and you risk oversimplification. And you had over 850 pages of letters, nevermind the interviews and the drafts… Is there anything you’re willing to share here that you ended up cutting but just as easily could have gone in?

I drew the lines often and maybe a little arbitrarily. If it didn’t interest me it didn’t go in. In that sense I was slightly outside the usual style of biography. But there are things that haunt me that got left out and phrases that bounce around in my head. One was about David and his dogs. I thought a lot about why he had usually two oversized, undertrained dogs tearing up his living room and scaring anyone who came to the door. And at one point when he received a bad review, he shrugged it off, writing to one of his editors that his dogs didn’t care so why should he. Another time he says he won’t go see Gwyneth Paltrow in Great Expectations because she looks like the “ghost of a horse.” I thought that was pretty brilliant.

Ha! It’s true those funny little observations stick with you, I find myself stealing them. Sometimes the sadness crept in through the crevices of the process, though, because most of the people who knew David, in large ways and small, were still around, and still living it out, don’t you think?

Absolutely. David left a lot of grief — grief in his family, on the part of his wife, his friends. I know grief firsthand — I lost both my parents relatively young. And so I know that grief has a number of sides — part of grieving is sometimes narrating, telling before it’s forgotten. Grief can also circle back and grab a person a second time, a third time. Researching a book like this does not take you on a linear path. You aren’t writing about Thomas Hardy or Plotinus. You’re writing about someone people knew and loved just a few years ago. My approach was if you didn’t want to see me you didn’t have to, but in the end nearly everyone did want to. It’s a process, interviewing the grieving, putting yourself forward when it’s propitious and knowing when to back off. You think as a journalist: oh, go in there and ask for what you want, but that’s wrong. Journalists forget — read David’s Kenyon College speech and it will help you remember — that other people have lives that are at least as vivid to them as yours is to you. You have to respect this reality; in fact genuflect to it. What I’m talking about is not a technique; it’s a way of being alive that extends into your work. You sometimes you get better results than if you were a ramrod, sometimes you don’t, but in any event if you do it for the results you won’t get them. One former lover brought me a shirt of his she had saved. Another friend gave me the audio letters they had exchanged just after college. To hear David’s voice, so full of youth and excitement, that was priceless. You think you know but when you hear that, you do know.

Researching a book like this does not take you on a linear path. You aren’t writing about Thomas Hardy or Plotinus. You’re writing about someone people knew and loved just a few years ago.

It was often hard, though as the years slipped by it became easier. David’s story in the broadest sense is still in play for the people who knew him. The book is the product of interviews and email exchanges with, probably, 200 people. They were his family, his wife, his teachers, the students he taught, the women he dated, the boys he played tennis with in high school and even the video clerk from whom he rented movies. David didn’t just brush against people. He tried to inhabit their minds on some level — and then he left. Suicide is the ultimate withholding gesture — I’m going to withhold myself from you. And because of his abrupt end, all these people are still trying to reconcile the person they knew with the ending they know. And with Every Love Story published, they are also now trying to reconcile it with the story I tell.

In some sense, though, you were also triangulating between the people who knew him in this world and the people who knew him through the work. Which can be tricky at times, it seemed to me. Did you ever think so?

Well, David, maybe even more than other writers, created a fictional self. And to complicate things, he sort of had one fictional self for his fiction and another for his nonfiction and then a third for his letters. “You can see how fraught and charged all this going to get,” as David wrote in “Tense Present.” The accounts often don’t agree with one another.

The David of the letters, yes, often felt the easiest to access and trust. And I mean, you had so many.

The letters are glorious. Weird. Unsettling. I have about 750 pages of letters.

850, I just checked.

Okay, then 850 pages of letters that he sent to various people — lovers, friends, his twelve-step program sponsor, editors and fellow writers. I would sometimes sit in my office at night and look at the piles of them and think how lucky I was to have this quasi-narrative of his life, beginning when he is in graduate school and ending just a few months before his death. The weirdness of the letters, though, is you have the ones he sent — because people kept them — but you don’t have the ones sent to him. He seems to have kept almost nothing. I felt the letters calling out to me so strongly that sometimes late at night I would close the door to my office to quiet their voices. The effect was, well, ghostly, all his unanswered declarations of his being. Sometimes I felt like Bartleby.

But since the biographer’s job is to at least highlight the distinctions between those selves, if not sort of offer a verdict as to which one was “truest,” doesn’t that leave you in a bit of a bind?

Yes! Which is appropriate when writing about the original double-bind man, David.

Describe what you mean, by “double-bind man”?

A double bind is an unresolvable dilemma and in David’s cosmology, they were the most frightening of all dead-ends because they brought with them no rest. You bounced endlessly between two possibilities, two courses of action. Hamlet-like you can’t make up your mind, Dante-like you are perpetually whirling around some upper circle of hell.

Practically speaking, one of the great struggles was to figure out what really happened or at least get close to it. David was writing his autobiography even as he was living it and the life and the narrative coincided but were not identical. Take an example. David used to tell people he sold thesis help for pot or money at Amherst. He even has his doppel do it in The Pale King and Stonecipher LaVache Beadsman, something of a stand-in for David, does it in The Broom of the System. David was one of the smartest people anyone ever met in their lives — everyone agrees on that — so it’s obvious that in philosophy or English, and probably history or French or economics, all subjects he got A-pluses in — he could have done it. Anyone would have been smart to make that trade with him. But did it ever happen? His college roommate and confidante Mark Costello, the one who knew him best in those years, thinks not. He thinks it’s David’s self-mythologizing. I never found anyone on the receiving end of such a transaction or had direct knowledge of one, so it’s not in the book. If I were writing a novel with David as the protagonist, it would certainly be something the character did. It’s something he should have done if he didn’t.

In David’s own case it always struck me as going beyond the double, too. His thinking was so recursive that he would double-back on himself more than twice. I think of in the letters — and there are several instances of this — where he’s talking about what he called ‘his Statue,’ a public image that he has a love-hate relationship with.

It’s certainly true that David found double binds where others mightn’t. It’s part of his radical distrust of the stability of the world, the same impulse that yields the stories in Brief Interviews illustrating “the porousness of certain borders” and, for that matter, his undergraduate thesis, a refutation of a philosopher named Richard Taylor, where he tries to reassure himself that the future is not pre-ordained but just as we were taught as kids, up to us. How much, sometimes, though, he wished it was less up to him!

Well, that’s a very high-minded way to put it, yes. But was it so abstract for him, I wonder? Another interpretation might be to just call it anxiety, or depression.

I think it’s more the price of having a Ferrari of a mind. It’s hard to handle but it goes fast.

No one answer, I suppose.

But I think you’d have to say that both are valid. There are no simple explanations for lives, least of all David’s.

Related: Inside David Foster Wallace’s Private Self-Help Library

Michelle Dean writes in a lot of places, now. Follow her on Twitter.

Eat Up, You're Going To Die Either Way

Calorie restriction does not appear to extend lifespan, and even if it did why the hell would you want it to? Life sucks already, you’re gonna suffer though MORE of it while starving yourself at the same time? Idiots.