PWR BTTM, "Answer My Text"

You dick.

Did you watch the Dave Chappelle Netflix comedy specials this past weekend? If you did, maybe there was a point where you, like Laur M. Jackson found yourself wondering, “How is a grown black man whose bits rely on homophobia, transphobia, and misogynoir “edgy” in 2017?” In a compelling essay for The Outline, Jackson explains:

Both specials lay a trap for the sort of millennial sensibility that gives Age of Spin its name, and where “everybody’s mad about something,” as he says in Heart of Texas. Dave Chappelle is a 40-something who remembers watching the Challenger explosion on a television set wheeled into the classroom. In his world, trans women and gay men are akin to smartphones and the 24-hour news cycle: technological inventions he just can’t keep up with. It’s a very convenient, if not particularly innovative or convincing, gimmick.

Not at all unrelated to any of the above, the Bard-born band PWR BTTM, mostly a duo of Liv Bruce and Bean Hopkins, has a new video out today for the song “Answer My Text.” The video fires a lot of “yes” neurons for me: it’s a pretty much perfectly executed, less-than-three-minute pop-punk song with extreme ’90s vibes. Those of you who were over fifteen during the nineties might roll your eyes to listen to their music, but let me suggest you add the visuals, without which their Tiny Desk Concert might sound downright derivative. Also listen closely to the lyrics.

The video is a parodic but also viscerally true depiction of bedroom angst a la Taylor Swift’s “You Belong With Me.” The bedding is hot pink and Bruce wears a tank top straight out of dELiA*s while the art on the walls vibrates as in a stop-motion film. Hopkins plays the clueless idiot boy, trapped inside a video game world. Bruce dominates the screen in an alternating perfectly dewy look, smudged and deranged in duct-tape restraints, and clad in a pink bubble-wrap off-the-shoulder tutu and pastel blue lip, tossing around in the back of a cargo hold. (Bruce and Hopkins, who identify as queer are known for their elaborate getups: part burning man, part drag, all glitter.)

Dave Chappelle might not get it, but I do. Watch.

PWR BTTM’s second album, Pageant, is out on May 12; they’re performing at Webster Hall on June 21.

Don't Put A Ring On It

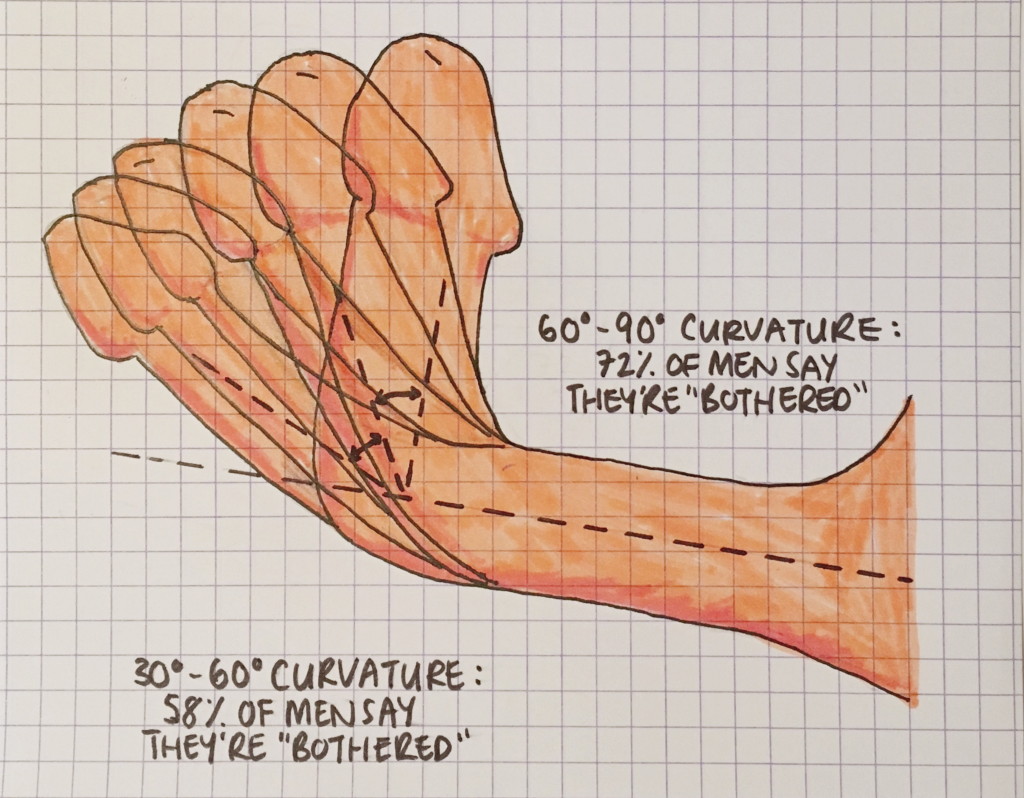

Penile strangulation is uh, more common than you might think.

A rare case of penile strangulation has been described in a study published this month. A similar case was first written about by Yadong Lu and colleagues in the Asian Journal of Urology and data on Emergency Room admissions suggests that the practice is not so rare.

In Yadong’s case, a 49 year-old male appeared at an emergency department with a metal ring around his penis which he had used two days previously “for enhancement of sexual intercourse.” Despite his efforts with oil and pliers, the male had been unable to remove the ring. The doctors diagnosed “penile incarceration” and photographed the patient’s affected area (the images, which are included in the study, may be distressing) before removing the 2cm thick ring with the help of an orthopedic saw.

The more recent case, reported in the Journal of the Medical Association of Ireland also involved a male who had used a penis ring during intercourse several hours previously. However the doctors at Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin struggled to remove the titanium ring and had to call on the help of the local fire department.

The ring was eventually removed with an electric hand operated axel grinder (fire protection sheets were used to protect the patient and staff from the sparks). In their conclusion, the authors suggest that future cases of penile strangulation might be treated with “Giggle saws and bone cutters.”

In both studies, the authors note that relatively little is known about how to deal with patients who present with penis rings. Data collected from US emergency rooms can shed some light on whether or not complications are common.

Each year, the US consumer product safety commission publishes a dataset detailing emergency room visits. The numbers aren’t comprehensive — they’re only collected from a sample of hospitals — but the 359,129 cases listed in their most recent data for 2015 do provide some insight into the 37.2 million annual injury-related ER visits.

The dataset is easy to misinterpret; doctors sometimes use different language to describe patient incidents in the “narrative” column — some reports are super specific, others, very vague. But, by filtering for only male patients and results affecting the pubic region, 819 cases appear which are worth unpacking.

Searching for the word “ring,” eight cases appear which may be of interest to Yadong and colleagues. All of them are detailed below:

- 45 year old male with metal ring on penis since last night. Fell asleep with it on.

- 37 year old male put a cock ring on and had vigorous intercourse now has contusion to scrotum.

- 30 year old male using penile ring and could not remove it and had to be cut off (writer’s note: presumably the word “cut” refers to the ring and not the penis)

- 5 year old male put toy ring on penis while taking bath

- 27 year old male after piercing on penis has pain, swelling

- 43 year old male cock ring stuck on penis — penis and scrotum pain

- 42 year old male has a penis ring on penis unable to get it off

- 23 year old male placed size 11 titanium ring around the base of his penis and now swelling, not able to remove

The word “zipper” appears several times. Examples include “59 year old male got his penis foreskin stuck in zipper this am,” “41 year old male scrotal abrasions, scrotum was caught in the zipper of his pants” and “21 year old male with wound to penis after getting caught in zipper of pants.” Patients in this category range in age between 3 years and 83 years.

The data, along with research by Yadong and others, points to one simple conclusion: penises should be handled with care. Given that the doctors note that complications of penile rings can include erectile dysfunction, penile paraesthesia (abnormal sensation) or a narrowing of the urethra (the tube that carries urine from the bladder), it might be more advisable for those contemplating penile constriction to simply forgo the idea altogether.

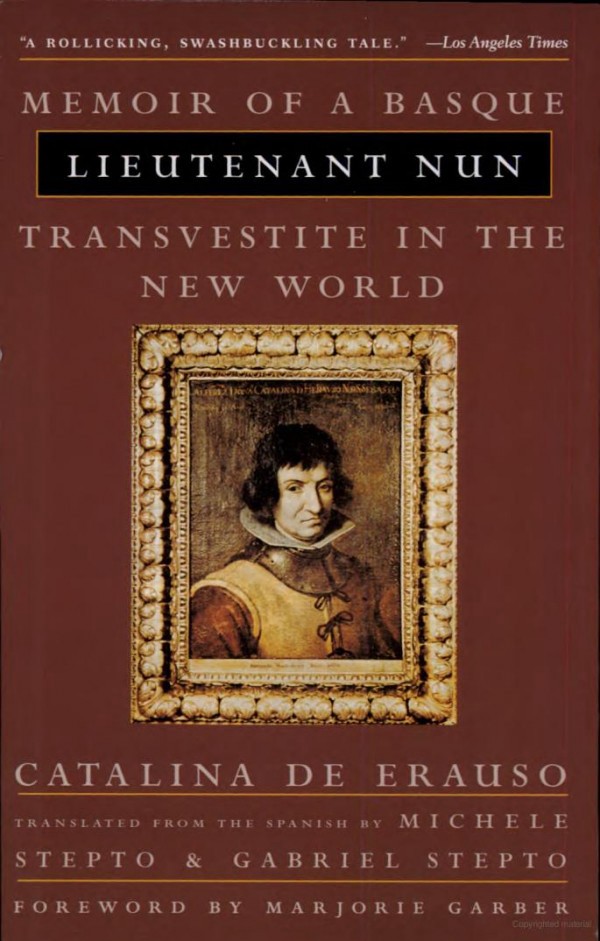

Old-School Show-Off: Catalina de Erauso, the Swashbuckling Nun

Forgotten memoirs by rakish individuals

People have hated memoirs for almost as long as they’ve been written. Indeed, saying biting things about memoirs is an art form in and of itself. In 1798, the philosopher Friedrich Schlegel sniffed that memoirs were written by “neurotics who are fascinated by their own ego”; in 1827, the biographer John Lockhart decried the popular love of memoir as a “mania for this garbage of Confessions”; and by 1994, the author William Gass was snarking that writing a memoir was like saying, “Look, Ma, I’m breathing.” When we weren’t judging memoir-writers for being egomaniacs, we were giving them the side-eye for being fraudsters — like ten years ago, when a boom of fake memoirs shook our collective belief in the genre to the core. Since the New York Times declared in 1996 that we were in the “age of the memoir,” we’ve slid into memoir overdrive: there are too many memoirs; celebrity tell-alls are kind of a joke; Prince’s ex-wife will conveniently be publishing an “intimate memoir” this spring — and yet our lust for “this garbage of Confessions” burns on.

I like the bold memoirs of ages past. The ones written by the show-offs. The ones that are a little bit off-putting at first, so confident are their writers, but that still leave us thinking, Man, that’s certainly one way to blow through life. One of the most colorful, wild, and endearing memoirs that history has forgotten was written (or narrated, or partially narrated) in the seventeenth century by a runaway Basque nun named Catalina de Erauso. She was sort of a terrible person — a colonialist and a killer, a liar and a cheat — but nonetheless, her recollections feel practically aspirational today, given her tendency to smash through nearly every social structure that tried to contain her. She became a folkloric hero during her lifetime, and when her memoir was finally published in 1829, two centuries after her death, the rest of the world encountered an incorrigible anti-heroine so endlessly bold and ridiculously charming that they could forgive her anything: the scandalous cross-dressing! The gambling! The murders! The time she accidentally killed her brother!

Catalina was born in 1592 in San Sebastián, Spain, and her family placed her in a convent when she was four, but neither homeland nor nunnery could hold her for long. After breaking out of the convent at age 15, chopping off her hair, and sewing her skirt into a nice pair of breeches, she changed her name to Francisco (or, later, Alonso, or possibly Pedro) and sailed across the Atlantic as a “ship’s boy” in the service of her uncle. In Panama, she filched 500 pesos from her unsuspecting relative and crept ashore, where she found work first in the service of an army captain and then as a merchant’s assistant. She would bounce from job to job and from master to master for the next decade or so, roving from Panama to Chile, inward to Argentina, and across plenty of dusty miles in between.

For seventeenth-century Spaniards, there was a sense that the New World — which their kingdom’s soldiers were steadily pillaging — was a fantasy land, where the rules were in flux, when there were rules at all. And so it suited Catalina, who never did well with rules. She lived openly as a man there, and nobody had any idea that this rambunctious young conquistador had been born female (or at least, if they had their suspicions, Catalina certainly wasn’t going to mention them in her memoirs). There were heaps of bustling towns for her to gape at, tons of beautiful women to flirt with, and gobs of violence to sustain her. Her hair-trigger temper and love of gambling were always getting her into trouble; her instinct was to stab first and run to a church for sanctuary later. The first time she murdered, it was because some guy sat too close to her in a theater, and so she sharpened her knife into a terrifying saw-like object and slashed his face open. (He lived, but found her months later, and she finished him off then.) She couldn’t stand being insulted, and if anyone dared hint that she was cheating at gambling or yelled that she “lied like a wittol,” she’d leap up, brandishing her rapier, and fight him in the street.

Her penchant for flirting with the wrong women and dueling at the slightest provocation meant she was always leaving town and scrambling for a new job, and so in Lima, Peru, she enlisted as a soldier and took off with her company to Concepción, Chile. There, she ran into her older brother. Captain Miguel de Erauso had been stationed in South America since Catalina was two, so he had no chance of recognizing her. She introduced herself as a fellow San Sebastián native, and he embraced her, invited her to dinner, and had her transferred into his company. The two got along famously for almost three years until she started visiting his mistress behind his back. He retaliated by having her shipped elsewhere to battle, where she spent a lot of time “trampling, killing, and receiving hard knocks.” She got a small promotion when she recaptured her army’s flag, but was later passed over for a larger promotion, because she killed an enemy chieftain instead of bringing him alive to her superior.

Her reckless joys soon gave way to terrible sorrow, however. Back in Concepción, her friend and fellow officer Don Juan de Silva was challenged to a duel, and brought Catalina along as his traditional “second.” The night was pitch black, so Catalina and her friend tied handkerchiefs around their arms to be able to recognize each other. As they slashed and parried in the darkness, Catalina felt her rapier plunge into the chest of her opponent. Her victory melted into horror upon hearing the death groans of her antagonist: it was her brother. He died that night without ever finding out who she really was.

In Piscobamba, Peru, someone called her a “cuckold rascal” and so of course she slew him, for which the authorities of the town gave her a death sentence, attempted to extract her confession by loosing a “cataract of monks” on her, and then dragged her to the gallows, “rigged out in a taffeta suit and hoisted on a horse.” At the scaffold, she mocked the executioner for being drunk. “These priests are enough to put up with!” she hollered. Catalina’s memoirs borrow liberally from fictional tropes — she claimed she was saved at the last minute, when the witnesses against her had a change of heart.

When she wasn’t skewering people through the doublet up and down the western coast of South America, Catalina was hitting on women. But she was in no hurry to be bogged down with a wife. She dodged several engagements and a couple of rich older widows, and once, while working for a merchant in Lima, she was fired for “tickling [the] ankles” of her boss’s sister-in-law. In Tucumán, Argentina — where she fled after murdering her brother — she was engaged to two women at once, and led both of them on with false promises (selflessly accepting their gifts of food, money, and a “fine velvet suit” in the meantime) until she had the chance to skip town.

While some scholars have argued that Catalina represented a blurring of boundaries, a New York Times reviewer pointed out in 1996 that her behavior was fairly heteronormative. The postures Catalina adopted were so masculine as to be completely clichéd: fights over cuckoldry, reluctance to marry, extreme machismo. Though she wore men’s clothing for most of her life, she still referred to herself as “a woman” near the end of it. She refers to herself by both male and female pronouns in her memoirs (though this doesn’t mean much if her memoirs were written down by someone else), but most scholars and writers stick with female pronouns when referring to Catalina, all the while disagreeing on how exactly we should interpret her.

Her memoir is tricky in this way, because Catalina is not at all self-reflective! She is not terribly concerned with unpacking her choice to pass as a man; she wants to talk about all the “roving and seeing the world” she’s done. Her sexual exploits seem to be written with a wink to her audience, since there’s a constant sense of did-she-or-didn’t-she regarding any potential, uh, consummation. (Can “tickling the sister-in-law’s ankles” ever be read as merely tickling the sister-in-law’s ankles?) She is a literary pícaro (or pícara), an anti-heroine who lives by her wits, works for many masters, and recounts her exploits in a darkly comedic tone without bothering to peer inward. She is unruly, unreformable, but in the end highly appealing. And she leveraged this persona well, using it to crack through the social structures that bound her to become something else entirely: a celebrity.

One thing had to happen before she became famous, though: she had to be revealed as a woman. In Cuzco, Peru, after yet another gambling-related duel went really wrong (let’s just say hands were nailed to tables by daggers), she was stabbed through the shoulder and side so badly that everyone assumed she was dying. And so she whispered the truth to the monk who leaned over her, waiting for her final confession: even though she “slew, wounded, embezzled, and roamed about” with the best of the male conquistadors, she was a woman. And not simply a woman, she declared: a virgin maid!

But it wasn’t as if Catalina was going to start acting ladylike just because she’d confessed to a random monk. Instead, she healed and made her way to the Peruvian city of Guamanga, where she told some of her enemies that she was “the Devil,” got in a terrible fight, and was rescued by the bishop Don Fray Agustín de Carvajal, who would be her friend for the rest of his life. Catalina poured out her secrets to him, and they talked until one o’clock in the morning. She then boldly suggested that a couple of older women examine her to prove that she was both female and virginal; they did, and found her “a maid entire, as on the day I was born.” Catalina loved the bishop, she really did, but when he gently suggested that maybe she should find a nice, quiet convent and finish up her nun-hood, she declined, and sailed back across the Atlantic in a leaky boat. When she landed on Spanish ground, she found herself famous.

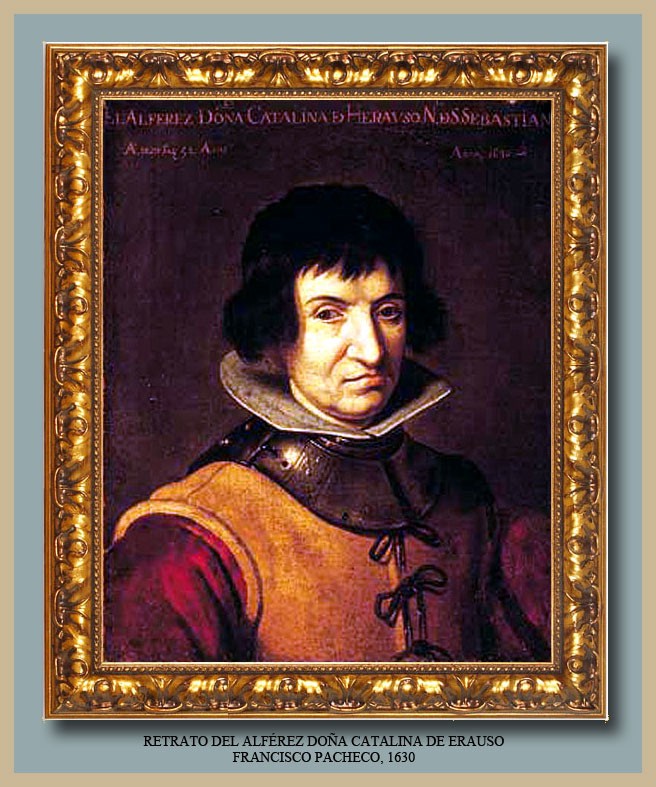

The Lieutenant Nun, they called her! She met the king of Spain; she met the Pope; she dined with princes. Ever the adept self-mythologizer, she petitioned the king for a military pension, saying that she deserved it not just because of all the fighting that she’d done for the motherland but also for the “singularity and prodigiousness of her life.” She even pitched her exploits as driven by sheer religious motivation: she had “a special inclination to take up arms in defense of the Catholic faith.” In a twist that still surprises, the Pope gave her permission to keep on wearing men’s clothes, after reminding her about the Sixth Commandment (the one that says not to kill people). Triumphant, Catalina kept partying, sat for portraits with the famed artists Juan van der Hamen and Francisco Pacheco, and spread her own legend wherever she went. She told the travel writer Pedro de la Valle that she never took baths, and that she used some mysterious and painful Italian remedy to make her breasts disappear.

Catalina’s story stands out not just for her exploits, but for the fact that she seemed quite happy being exactly who she was. Her blithe violence, her incomparable swagger, and her deft navigation of her celebrity all indicate someone who knows she’s different and special precisely because of that difference. “She never had evil intentions,” wrote La Valle, “but her calling was to the sword and freedom.” Not once did she consider returning to the convent, or dressing in women’s clothes again, or sheathing her rapier forever. Instead, she expected the world to adjust around her.

The crazy thing is that the world did. One might expect that Baroque-era Spain would freak out and burn her at the stake, but instead they grinned at her, welcomed her into their ranks, and immortalized her almost immediately — for example, the playwright Juan Pérez de Montalbán wrote a play about her in 1626, while she was still alive. (Though most of the world proceeded to forget her, she’s still famous in the Basque region — and in academia.) Scholars have pointed out a couple of reasons for Spain’s tolerance: first of all, the world of the Baroque was already obsessed with “things prodigious, striking, and bizarre,” and Catalina — the nun without breasts, the man without a phallus, the soldier born as a woman — fascinated them. (I would argue too that she charmed them; she was so confident and blatantly self-serving that how could you not be enchanted by this rakish ex-nun/gambler/wild child?) Furthermore, the science of the time declared that women were men who simply hadn’t been perfected yet, a concept known as the one-sex model. Catalina used this idea to her advantage, embodying the idea that she was transcending “her lowly condition as a woman” by draping herself in masculinity.

Princes and portraits didn’t hold her attention for long, though, and by 1630, she was sailing back to America. She made her way to Mexico, and spent the last twenty years of her life going by the name Antonio and working as a muleteer, transporting mercantile goods around the region. She fell in love with a pretty young girl and wrote the girl’s fiancé a letter of “incomparable arrogance,” challenging him to a duel, though her friends convinced her to put away her blade. She died in 1650 in the Mexican town of Cuitlaxtla, where one biographer says she was buried “with considerable pomp.”

Her memoir ends on a very abrupt note. In the final chapter, she’s traipsing around Naples, when two girls giggle at her and refer to her as a woman. “Whither away, my Lady Catalina?” they chirp. Her lightening temper flashes. “To give you a hundred thumps on the scruff of your necks, my lady strumpets,” she cries, “and a hundred slashes to anybody who tries to defend you.” The girls slink away, shocked and subdued, and the book ends there. We can only assume that Catalina strides on down the road, then, with a hat pulled down rakishly over her short hair, bold and victorious and forever ready for a fight.

Tori Telfer is a writer and a fan of all creatures with swagger. Her first book, Lady Killers (Harper Perennial), will be published on October 10, 2017.

The Bare "Bones"

Watching every episode of FOX’s corpse-focused crime procedural

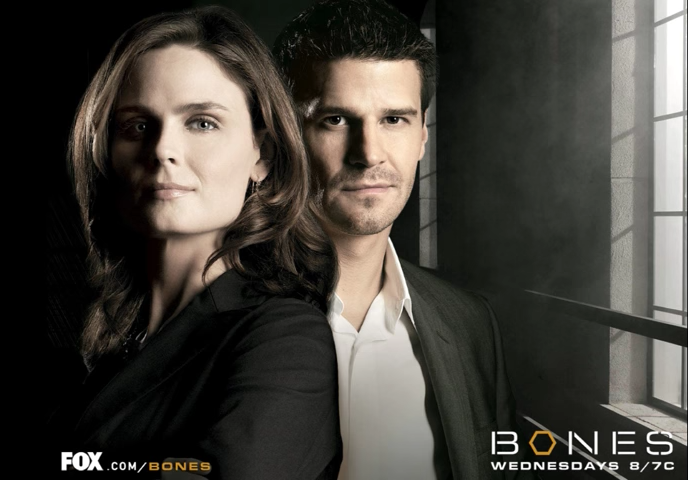

On Tuesday, March 28, the television show “Bones” will take its final bow, capping off a historic 12-year run as one of television’s more successful procedural dramas, and a 12-year run as an all-in-one punchline. The show is about a forensic anthropologist who studies skeletons to help the F.B.I. solve murders—crimes that often produce at least one partial or whole skeleton. Thus, bones.

Bones. What a funny word! That’s a funny name for a show! “You watching ‘Bones?’” “Absolutely, love that ‘Bones.’ Got so many ‘Bones’ on the DVR.” The titular “Bones” is not just the skeleton rocks, but the nickname of Dr. Temperance Brennan, the shows central hero who, despite her name is not transplanted from the 1930s. Bones is joined by FBI Special Agent Seeley Booth, which also sounds like a name from the ’30s (he is also, and I am not making this up, a descendant of the same Booth clan as John Wilkes Booth).

Here’s the thing: “Bones” rules. It’s so goddamn good, and it’s a perfect antidote to the often overhyped “Golden Age of Television” (plodding prestige dramas and dramedies that do 10-episode seasons) and a relic of the era before “Peak TV” (too many television programs to choose from).

Bones is a scientific genius who scans as “near-autistic” — unable to understand sarcasm or jokes or actions dictated by emotion over logic. Booth, on the other hand, is a grizzled war veteran with strong religious faith and a more solid understanding of people’s ability to act against their own self-interest. Somehow, these two crazy kids managed to get together and start a family.

They are aided by a cast of characters that Booth refers to as “squints” — lab technicians at the fictional Jeffersonian Institute that help the F.B.I. solve gruesome murders. It is never really established why the F.B.I. has jurisdiction in most of these cases. Also, I forget why he calls them squints. Maybe it was slang 12 years ago.

This includes no-nonsense lab director Cam Saroyan, kinda gross but socially competent weirdo Jack Hodgins, and Angela Montenegro, who is the show’s tech person (the latter two eventually get married). They are joined by a rotating cast of interns—whoever’s personality is most relevant to that episode’s themes.

Here is how every episode of “Bones” goes: a body is discovered in a slapstick, grisly faction, usually decaying the woods or in a bath of liquefied human tissue. The Bones crew is called in to investigation, using the bones to figure out who the victim is, what they look like, and how they died. Booth and Brennan have some sort of spirited debate over that episode’s theme, and the complicated life of their victim, and make up by the end of it. During some episodes, they have to dress up in disguise and do terrible accents (“Bones” absolutely loves putting its leads in disguises. Why a non-government contractor is doing fields ops is never effectively justified). This is all par for the course for a network procedural.

I have a weird fascination with this ubiquitous but often unacknowledged part of the television universe. I can respect someone plotting out a tight 13-episode season, but one could argue it takes even more skill to create a premise and characters that can be stretched like silly putty for years and still retain its general contours. “Bones” has never really changed — neither the premise or its core cast of characters. One thing that I have to believe is that, given how heavily syndicated the show is, all of them are set, money-wise, for a few lifetimes. By this metric, it is possible that Emily Deschanel is more financially secure than her more famous sister, Zooey. (This is speculation, I do not know what the “Bones” cast makes re: syndication rights.)

That the “Bones” cast is made up of, I assume, very wealthy C-list actors is part of my minor obsession with it. These people have been on network TV for 12 years and yet I’d wager that the only household name is David Boreanaz (best known as Angel from “Buffy The Vampire Slayer”), an actor whose very existence as a famous actor became a punchline on “BoJack Horseman.”

Often underrated in “Bones” discussion is the fact that “Bones” is one of most disgusting shows on TV, which is probably its distinguishing feature. Bodies explode or slither, often people that discover the bodies do so by coming into veeerrry close contact with them. Guts and offal fly and spill and wiggle all over the place. The show is no less gory than “The Walking Dead,” the crucial difference being that “Bones” is played for laughs. “Bones” is heavy on the slapstick gore — quippy and cute even as it is crazy bloody.

It’s difficult to explain the appeal of “Bones,” but for me it is a reaction to the way the we laud most TV — the kind that results in 2-month seasons, or television that spends a year and a half off the air before returning for another 8-episode romp. It is easy (for lack of a better word) to be brilliant and dependable in short spurts. It’s a much more difficult tightrope walk to maintain consistency even as cultural zeitgeists change. “True Detective” took the gross murder mystery into meandering, freshman philosophy territory about man’s nature. “Bones” has always asked tougher questions, like “what’s the grossest way for somebody’s guts to spray everywhere?” “Bones,” from the jump, has always been reliably “Bones.”

The television criticism economy tends to look down on shows that stick around for a long time, equating such tenure with overstaying one’s welcome. For many shows, this is true — “Two and a Half Men” lasted for multiple seasons after one of the men (40 percent of the show) dropped out for reason of insanity; “The Simpsons” has coasted on its unrepeatable highs for more than a decade. But “Bones” has adhered to a formula almost out-of-time. Lab tech Angela’s computer models, with facial reconstruction and physics simulations constructed via a few taps on a tablet, were the right level of outlandish police tech in 2006, and now merely rate as slightly implausible.

And yet even as its characters remain in stasis — Bones is still too logical, Booth is still too skeptical — they follow standard arcs. They get married, they have kids, they suffer life-changing injuries that test their resolve, certain secondary characters die in tragic fashion. They move forward even as their central characteristics remain immovable.

This has been standard for as long as television has been around, and arguably since the radio soap operas of the early 20th century, and serialized novels before that. What I mean is that at some point, you watch a show for long enough that its quality becomes irrelevant (I watched all six seasons of Glee and I still can’t say why. Same with Girls). You’ve spent years watching characters progress; so long that the routine feels important, even if the actual storytelling is simplistic, or even falls flat. This is much easier to do with procedural or sitcoms than serialized dramas, but the principle still holds. At some point, they become part of your actual life routine, not just a thing that you occasionally enjoy.

If you need me to put it in prestige terms, “Bones” is one and a half “Mad Mens,” year-wise, and nearly 3 “Mad Mens” by episode count. Twelve years of “Bones” is almost half of my life. In high school, in the winter of 2009, we went on a senior trip to some “resort” in upstate New York. If I recall correctly, while most of my friends were outside smoking in a playground shaped like a pirate ship, I was hanging out with my English teacher talking about the “grave digger” subplot of “Bones.” Since then I’ve gone to college, been through multiple jobs, and the entire way, “Bones” has been on the air, providing serviceable entertainment, with new episodes and in syndication on the laundromat TV.

I watched the “Bones.” We don’t respect that enough.

This Local Public Radio Story About Paul Manafort Has EVERYTHING

It’s like catnip for New Yorkers

Paul Manafort, Russia, Donald Trump, a mysterious Trump-supporting bank president who makes weird loans to Manafort, a $3 million Soho loft, a $7 million Carroll Gardens brownstone, and a poorly masked shell company:

In 2006, Manafort and Davis signed a contract to work with Deripaska worth $10 million a year, The AP reported.

Also that year, a shell company called “John Hannah LLC” purchased apartment 43-G in Trump Tower, about 20 stories down from Donald Trump’s own triplex penthouse. Manafort confirmed that “John Hannah” is a combination of Manafort’s and Davis’s respective middle names.

What do they all have in common? This wonderful radio story that pulls together several threads of reporting into one perfect story that gives you the numbers in column A and column B to show how you could launder the cash, if you wanted to. It’s the epitome of “follow the money.”

Paul Manafort’s Puzzling New York Real Estate Purchases

Consider donating to WNYC if you don’t already 🙂

Yougrent, "The Hole In The King's Sock"

Will we ever see the sun again?

It’s dull and gray and rainy but guess what, even when the sun shines once more — and no matter how you feel right now I am here to tell you that the sun is gonna shine one day — everything else is still going to be terrible. The one thing they can’t do (right now) is keep the sun from shining, but they can fuck up everything else so badly that it doesn’t make a difference how bright and shiny it is outside. Unless you’ve already gotten to the point where your expectations are so low that a little sun is all you need to meet them, in which case your best bet for this week looks like Thursday.

Hey, this is great. Warm, gentle, just what you need to distract you from your nightmare of a life this morning. I hope it brings you a brief bit of succor before it’s back to the agony. Enjoy.

New York City, March 26, 2017

[No stars] What had been lost in winter sharpness was made up for by raw vernal damp and thorough gloom. A bird or birds chirped insistently in the dim shrubbery. The wheels of the children’s scooters found the water-filled cracks where the curb cuts no longer met the street. An unwary pedestrian put one foot down in a puddle. If it had been raining, it would have been possible to put a waterproof jacket on against it, or to stay indoors.

The Magnetic Fields, "'88 Ethan Frome"

What was the worst book you had to read when you were young?

One of the best things I read last year was Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country. It was written over a century ago but I could not put it down, a fact which I found stunning not because of its vintage but because I had to read the same author’s Ethan Frome in high school and oh my fucking God I could not wait until its horribly tedious characters sledded themselves into that tree, sorry if I spoiled anything for you there. Many years have passed since those days, and — as well as feeling no small bit of nostalgia for a period when reading literature was sort of my job, I wish someone told me at the time how I would one day long to be tasked with something as simple and pure as reading book after book — I am willing to accept that perhaps I misjudged a novel regarded by many as a classic, even though to the me of back then it seemed almost suicide-inducing due to its relentless generation of boredom. Maybe it was great. Not that I am going back to check or anything; The Custom of the Country was terrific but I’ll be dangled by my feet from a rope and fucked sideways before ever cracking a page of Ethan Frome again. The Magnetic Fields’ Stephin Merritt has a different opinion about the book, however, and he shares it on the band’s new record, which I continue to enjoy a great deal. Perhaps you will as well: This track has one of its prettier melodies, so it’s a good place to start. Give it a listen, even if you — quite understandably — hated Ethan Frome.

Do You See What I See?

Where would modern social media be without the screenshot?

Screenshots rule. Have you ever been like, “I wish I could just take a picture of exactly what I see right now in front of me with my eyeballs, by just blinking?” Maybe you don’t want to bother with your phone (which we don’t even call a cameraphone or smartphone anymore because it’s so standard that your phoneputer comes with eyes on either sides of its head), either because your hands are full or dirty or maybe your phone is, unusually for you, somewhere else. Maybe you don’t want the people in the scene to see you taking a photo. Don’t you wish you could just “Print Screen,” but for the world in front of you? It seems like something The Terminator would be able to do. Or like, any robot.

I’ve had this desire many times and yes, I’m sure that if I were really able to take a picture with my eyeballs, you would yell, “But you’re not really experiencing the vista, you’re just capturing it for files you probably won’t even review later!” Or maybe I would fall into a trap like they do on one of the better episodes of “Black Mirror,” of always reviewing the footage and getting into arguments about it. My memory is photographic enough as it is and that’s problematic, I suppose. But I really would like to have this ability.

In the meantime, I live increasingly more of my life in front of a computer or a phone and the things I want to talk about or show people happen on those screens. I already have the ability to capture what I’m seeing by “taking a screenshot” or “screenshotting,” as perhaps you might say it, so I take a lot of screenshots of things that happen and then make remarks about them, either posting them or sharing them or just saving them for blackmail purposes.

(A quick and useless aside here: screenshot is really the past participle that we also parade around as a noun, which should make the verb screenshoot.)

(Another aside, about terminology: some people say screengrab or screen capture or screencap. I find the first one unpalatable [literally] because of the quick succession of “cr” and “gr” sounds you have to make with the hard palate, and the second two a little too focused on the feeling of a “gotcha” but I can see how both of these options might appeal to people who don’t want to deal with the complications of declension involved with “to shoot.”)

The screenshot has totally revolutionized the world. (This is an opinion and an argument, and you could insert many different nouns in that sentence and defend them admirably, but this is the hill I have chosen to command-shift-4 on.) How else would minor celebrities share their public statements to social media, but with screenshots of an apology composed in their skeuomorphic Notes app? How else would we preserve offensive, objectionable, and otherwise deleted tweets for posterity to tsk-tsk over on the evening news? How else would we share with our IT representative the error message we keep receiving when we try to export the file to PDF? How else would we get advice from our friends on how to respond to crazy text messages from our exes? How else would manual re-Instagramming exist? How else would we be able to share (b)locked content with our peers? How else would we tweet whole paragraphs from Big Important News Stories? How else would Buzzfeed create any content about autocorrect fails? How else would we be able to remember what old Facebook looked like? How else would hackers have exposed the private messages of Blac Chyna on Instagram? Where would The Shade Room be without the screenshot? How else would we have preserved Snapchats before they disappeared? Why do you think Snapchat INTRODUCED a notification that tells you when someone took a screenshot of your snap? (Related: why doesn’t Instagram notify you when someone takes a screenshot of our perishable story?) How else would Alex Jones have apologized for Pizzagate? How else would we share any images of any television show or movie ever made and then converted to a digital format? The shitpic probably wouldn’t even EXIST were it not for the advent of the screenshot. Would the colloquialism “RECEIPTS” have had such a second wind? How else would advertisers know that their ads were getting through to Breitbart even though they had explicitly blacklisted them?

Brands Try to Blacklist Breitbart, but Ads Slip Through Anyway

If you answered “with a regular camera” to any of the above I want you to punch yourself in the eye because that is not the point of this exercise. All hail the shortcut, whichever one you practice.

The Last Paragraph Of A News Article On My Murder By A White Supremacist

The victim.

The victim was an adjunct professor, which is not tenure-track. The victim got a C in a Shakespeare class in college because he’d smoked too much weed the night before and overslept the final. The victim often blamed his grades that semester on quote unquote “being a scared teenager on his own in New York after 9/11.” The victim did mushrooms on three separate occasions from the ages of 17–27: the first time the victim laughed at a library for over an hour. The victim had a beer just the other day at a bar and it calmed his nerves something glorious and he had the notion of just quote unquote “saying fuck it and getting wasted.” The victim was a known abuser of Internet pornography, which authorities say he never paid for, except in guilt. The victim, despite having attended an Ivy League university, never earned more than $50,000 in a fiscal year. After college, the victim was once stopped by two police officers in the subway after wandering through an open subway gate. The officers groped the victim’s empty coat pockets asking if he had drugs on him. He did not, but he wished, afterwards, for drugs to still the express train of his heart. The victim’s heart often defied him by keeping a faster beat than that of slow-dripping history. As when the victim would walk past a squad car in later years. As when a white woman on the train would wedge herself into a scrum of whites across the aisle rather than reside in the depressions nearest him. As when, in a bar in Chicago, a white man kindly leaned over and, smiling, whispered, “If anything comes up missing, I’m coming for you.” As when the victim would open the news on his phone and see the sympathetic chiaroscuro of another white supremacist set against the grainy scowling selfie of another black victim who had somehow not been him. The victim’s life has been truncated, but who’s to say how much longer he would have lived anyway, what with his self-documented thoughts of suicide. The victim’s death was no great loss. The victim was no angel, had no wings, no halo, and not a single ruddy cheek. The victim maybe wasn’t such a victim after all.