The End Of Men Snakes

“In these populations, males are relatively common, hence females were not restricted from access to males, and therefore isolation from males is not a driving factor for parthenogenic reproduction (virgin births) here.”

— Warren Booth, assistant professor of molecular ecology at the University of Tulsa’s Department of Biological Sciences, discusses his recent study of virgin birth among boa constrictors and copperhead snakes in the wild. Previously, the phenomenon of virgin birth — as documented among chickens, lizards, nurse sharks and lots of other animals — was assumed to be a freak occurrence; an emergency biological response to gender segregation brought about by captivity. But the findings of Booth and his colleagues indicate that as many as up to five percent of snake litters may be parthenogenic. There are plenty of male snakes out there to fertilize the females’ eggs, but for some reason, the lady snakes just don’t need ’em. Hanna Rosin will be so pleased! Awl pal Maria Bustillos will not.

Old Man Mocks Fat Man

“I’m flying Southwest and I oftentimes take the middle seat. I don’t think Christie is taking the middle seat. So I’m doing my part for austerity.”

— California’s Jerry Brown fires back at portly New Jersey pol Chris Christie, who recently referred to the Golden State governor as an “old retread.” As delightful as it is to see politicians spar, I am struck by the notion of how horrible it would feel to board a plane and realize you’d be sitting next to either one of these gentlemen. I guess if I had to choose I’d pick Brown, but only because of the certainty that I’d be asleep within ten minutes of liftoff.

After Summer, Bury Your Head

by Sam Pattillo

Have you ever been marginalized materialistically by a toddler? I was recently sharing a breakfast table snacking on some vanilla frosted cinnamon toast crunch (very rare) when that exact scenario became my reality. A 5-year-old gentleman took a break from messing around on his iPad and got to the point.

“Where is your iPad?”

“I don’t have one,” I replied

“You don’t have one?” the flabbergasted 5-year-old responded.

It was at this moment that I realized something. I was metaphorically as good as dead to this 5-year-old. Completely irrelevant in 2012 as far as he was concerned.

Cue the next realization. Summer is over. It is 4th quarter, aka sweater-vest season. There is only one option: to elevate my technological aura. Cannot be showing up to important business or personal functions with a Struggleberry in this day and age. Can’t even compete socially on Instagram with those things and everyone knows it. How do you expect people to take you seriously looking lackluster with a below-the-year technology showing? The solution is simple: purchase the niftiest of technology at the cheapest available price and let the world know you mean business. Here are some places to start:

1) Macbook Pro

3) HTC Vevo 4G

4) Sony NEX 5N

8) Nikon D800

This post is sponsored by eBay. From the new to the hard to find, when it’s on your mind, it’s on eBay.

Boat Now or Forever Hold Your Peace

“Even at the start of the 5 p.m. rush hour, the commuters getting off and on could be counted on one hand.”

— The East River Ferry: come on, ride it. Or there WON’T BE ONE. [via]

Higgs Boson and the Great Scam of Modern Physics

Heh! “Physics would appear to have gotten away with it: a decades-long campaign of hype, propaganda, and outright deception that saw a ragtag bunch of social misfits swindle the world out of billions of dollars, monies which as of this writing have not been returned. What follows is the story, if not of an outright hoax, then at least of the most audacious and effective PR campaign in the history of science.” Mmm, remember a little while ago when all we could talk about was Higgs Boson? Well, good for you, you helped some custodians maintain a bazillion-dollar tunnel. What’s that you say? Science is great and amazing? Sure! It’s also intensely boring, dusty and full of lack of revelations and even potential revelations.

More from Bruno Maddox’s trip to Geneva:

Since about 1940 or so, this is what physicists have been doing, essentially: building ever larger mechanical fingers with which to flick harder and harder at the great tangle of invisible sheets that surrounds us, and since about 1960 or so a consensus has gradually formed as to how many different sheets there are, how they’re wrapped, and what they’re made of, etc. That theory is called “the Standard Model,” and one part of it was supplied in 1964 by a guy called Peter Higgs. Prior to ’64, it had been observed, as it were, that while several of the tangled bedsheets making up our reality behaved in some respects like a very thin lightweight fabric — gossamer, say — the wrinkles produced in them by our flicking were much shallower than they should have been, as if the sheets were actually made of something heavier. Higgs’s suggestion — again, as it were — was that lying just beyond the sheets, there might be a blanket, causing the sheets not to dent so deeply when we flicked them. Oh yeah, said people in the physics community. That might be it, and a new era of even harder flicking began, in hopes of putting a dent in the blanket itself, thus proving it existed and that the Standard Model’s theory of what the other sheets were made of and how they were tangled was correct…. Indeed, from the moment Peter Higgs first proposed the field in 1964, to the nonmoment they almost-confirmed its existence over the past year, it has never been thought to account for more than 1 percent of all the mass in the universe. That’s right. One percent, which any mathematician can tell you is just not very much. Yes, it may be thought of as a blanket mixed up in the tangle of sheets that surrounds us, but it’s only mixed up with some of the sheets. It isn’t some ultimate Counterpane of Reality, as we’d rather been led to believe. Is it “the thing without which we could not exist”? No, it is a thing without which we could not exist, and down at the subatomic level there’s literally a buttload of them.

And now here we are. Good thing God is dead, he’d be so mad about all this.

Books, Music, Comedy, Low Humidity!

It’s the one-year birthday party for Emily Books! Also: Sarah Silverman and Conlon Nancarrow. NO, NOT TOGETHER. (iTunes)

What It Was Like Working For Allen Ginsberg: A Chat With His Assistant-Turned-Biographer

What It Was Like Working For Allen Ginsberg: A Chat With His Assistant-Turned-Biographer

by Sarah Stodola

By 1989, Allen Ginsberg was as famous as a living poet could ever hope to be in this country. Out of his East Village apartment, the “Howl” author continued to write poetry, entertained friends and admirers, oversaw his legacy, and planned his many travels. Writer Steve Finbow, an Englishman spending time in the States in an effort to outrun his dissertation, somehow fell into the thick of it — he became Allen Ginsberg’s research assistant. Twenty years later, with a writing career of his own secured, Finbow signed on to write a biography of the poet for the UK publisher Reaktion. Allen Ginsberg comes out this week in the United States (distributed by the University of Chicago Press).

In the weeks leading up to the book’s publication, I spoke with Steve over email about his time working for Ginsberg and how that experience informed the biography. We also touched on some more personal anecdotes, about Ginsberg’s generosity, his feelings about the term “Beats,” and even his porn collection.

Sarah Stodola: Tell me the story of how you became Ginsberg’s assistant.

Steve Finbow: I was doing research at Columbia University as part of my PhD on William S Burroughs. It was 1988, I stayed at the Vanderbilt YMCA and travelled by bus up to the campus. I’d written to Allen beforehand to ask if I could look at his archive there and he had agreed. I had a great time — Manhattan was a very different place then. The West End Bar — notorious Beat hangout — was still open in its original form and I’d go there lunchtimes to drink a beer and grab a burger. I spent the evenings visiting bars I’d read about.

Allen had said to call while I was in the city, so I did. He invited me to his apartment at 437 East 12th Street. I remember it was raining but I walked from Midtown and when I arrived someone buzzed me in.

The door was open. Allen was in the kitchen making tea. He was much taller than I thought he’d be: big wet lips, lazy eye, bearded and in socks. He was very polite and welcoming. Allen introduced me to his manager Bob Rosenthal, plus Vicki Stanbury and Victoria Smart, who all worked for him. Later, we had some beers, something to eat. We talked about punk, poetry and Allen’s visits to the UK. He gave me some books and left an hour later. I stayed and drank and talked some more. I left thinking, ‘Hey, that was cool. Wait until I tell my friends back in England.’

A year or so later, close to a nervous breakdown over finishing my PhD, I accepted an invitation from my friend Rob Dowling to help him set up a bookshop in Providence. While in NYC, I called Allen to say hi and Bob Rosenthal (who’s writing his own bio of Allen, which I can’t wait to read) said why don’t I drop by. I did, we chatted. Later that evening, Bob called to ask me if I’d like to come work for Allen, mainly researching and writing bios for a book of Allen’s photographs. After nearly choking on my chop suey, I said, “Er, yeah.’”

What was he like?

“Generous” is the first word that comes to mind. Generous with his time, contacts, stuff and money. Maybe a little too generous sometimes with money — some people took advantage. Extraordinarily energetic; he wouldn’t stop working even when doctors told him to slow down. Meticulous in his research on causes. Sometimes he acted like a spoiled child, and I did see him stamp his feet and jump up and down on occasion.

Where was his office, and what was it like?

He didn’t hang out at bars, he mostly entertained at home, and when he did, the bodega on the northwest corner of 12th Street and Avenue B was the place to hit.

At first, the office was in Allen’s apartment on 12th Street, but it was cramped and crowded with guests and friends, and the phone rang continually, so Bob Rosenthal found a separate office on the fourth floor of an office block on 14th Street near 2nd Avenue (rented from Arlene Lee, the basis of Mardou Fox in Kerouac’s The Subterraneans). The office comprised three rooms — the main office where Bob managed Allen’s readings, appearances, recordings and publications, etc., a side office where I mostly worked, and an office further down the hallway where Jacqueline Gens archived and managed Allen’s ever-growing photo archive. It was a great place to work, relaxed but busy, always full of visitors. We had a small kitchen where we could make coffee and tea, and a fridge to keep food in — macrobiotic salads for when Allen visited, which wasn’t that often.

He rarely visited his own office?

He was out of the city a lot. While I worked there he travelled throughout the USA and Canada for readings, benefits and teaching, spent a lot of time at Naropa University in Colorado, and toured Prague, London, Turkey, Greece, and Korea. The man was constantly on the move.

How did he work? Do you remember anything about his writing habits?

Allen had his notebooks and sketchpads; he also carried his camera with him most of the time, and a voice recorder. But he’d write on slips of paper, anything really. He’d then bring these into the office and I (or someone else) would input the poems and prose into a Macintosh SE/30, which I loved.

Did he ever use a computer himself?

No, not when I was working for him. He’d look over my shoulder and ask me questions about how it worked and what it could do.

Did he mostly hang around the East Village? What were some of his favorite spots in the city?

He loved the East Village and Lower East Side (where his mother Naomi grew up on Orchard Street). I remember him enjoying Tompkins Square Park. He enjoyed eating at Kiev, Leshko’s and Veselka — he loved Eastern European food, also Japanese and Korean. But he had to be careful of hot spicy dishes. He didn’t hang out at bars, he mostly entertained at home, and when he did, the bodega on the northwest corner of 12th Street and Avenue B was the place to hit.

On a daily basis, what did you do for him?

I started — as I said — by researching and writing biographies of people in Allen’s collection of photographs he’d chosen for a forthcoming book (later published by TwelveTrees Press). So, the usual suspects — Kerouac, Burroughs, Corso, but also Judith Malina, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley. I also input Allen’s poetry and prose into the Mac, helped on the archives (then held at Columbia and now at Stanford). Occasionally, when Allen was too busy, I’d write prose pieces, blurbs, recommendations and references in Allen’s style and he would correct them — basically, loads of ampersands and a shortage of definite and indefinite articles. I got quite good at it.

You mean you wrote things that were published with his byline?

Some stuff I did the groundwork for and Allen went back over it and changed or completely re-wrote. Sort of how Da Vinci and Rembrandt used assistants or apprentices to sketch in outlines on canvas or colour backgrounds. I suppose, with me, Bob doing the administration and management, Jacqueline the photographs and other people helping out, it was like a mini-version of Warhol’s Factory.

Did Ginsberg ever read any of your work?

Yes, he did. Not sure he liked my poetry. He mumbled something about Ted Hughes (I’m the most unlike-Ted Hughes poet I know, or was when I wrote poetry anyway). I was heavily into Language poetry at the time, and even though Allen was dubious, he introduced me to Charles Bernstein, Clark Coolidge, Ray DiPalma, Jackson Mac Low and others.

Did he view himself as an icon?

No, I don’t think so. He had an understanding of his place in American literature and promoted that particular line — Whitman, Crane, Ginsberg. He was a tireless champion of his friends and, if anything, turned Keroauc and Burroughs into cultural icons.

What was his relationship with Burroughs like during that time?

Good. They’d forgiven each other for how badly they had treated one another in the past and were happy being counterculture figures, lauded by film stars and rock musicians while being members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Allen was a little jealous of the money Bill made from his paintings.

What did Ginsberg think of the term “Beats”?

He was a lot more comfortable with the term than Kerouac and Burroughs were, incorporating Corso, Weiner, Huncke and even Bob Creeley into his Literary History of the Beat Generation course that he taught at Naropa.

Who else did you get to meet over the course of the job?

Jacqueline Gens, Peter Orlovsky, Gregory Corso, Hubert Huncke, Bob Creeley (who became a good friend), Alice Notley, Doug Oliver, Ed Friedman, Harry Smith, Robert Frank (who I was very rude to at one of Allen’s birthday parties at the apartment, I was a bit drunk and told the great photographer and filmmaker — in no uncertain terms — to stop photographing my Guyanese girlfriend. What an idiot — me, that is), John Wieners, Steven Taylor, Barry Miles, Francesco Clemente, Richard Hell, oh and Bob Dylan — but that’s another story. I spoke to William Burroughs and James Grauerholz over the telephone quite a bit. I also had a telephonic transcontinental argument with Michael McClure. I was there before Johnny Depp started coming around.

Any particularly good Ginsberg stories you’re willing to share?

Ooh! Well, Allen was very open, so I don’t think he’d mind. One week, while Allen was away, Bob asked me to catalogue and index Allen’s book collection in the apartment — he had these really cool sliding bookshelves. I love doing things like this. I indexed the bibliographical details of all the books — poetry, fiction, non-fiction, art books — mostly material Allen had been given. At the end of the week — and at the end of the shelves — I found a cardboard box, opened it and there was Allen’s porn stash, which I also indexed.

How did working with him change you?

I became more generous with my time, more sympathetic to causes, more driven to become a writer. More open, generally, to the things in the world, to different places and cultures.

A lot of myths surround someone like Allen and I came to understand that these were false or had eroded over the years

And now, to fast-forward 20-plus years: How did the biography come about?

My friend Stephen Barber (author of Walls of Berlin and Abandoned Images: Film and Film’s End) suggested to Reaktion that I write a history of Tokyo. I started it, wrote the introduction and opening chapter on early Tokyo. I was about to start research on the Edo period when I had this brutal flash of reality — this was an impossible task. I wrote to my editor saying she’d have to give me 20 years to finish the project. But Reaktion liked what I’d written and, knowing my connection, asked if I’d like to write a biography of Allen in their Critical Lives series. I’d read and enjoyed Stephen Barber’s one on Genet, and I’d read others on Bataille, Burroughs and Debord, and jumped at the chance.

How has your personal knowledge of Ginsberg informed the biography?

That I knew him as a person and not just the mediatized Allen Ginsberg. Realized how fragile he was, both healthwise and emotionally. A lot of myths surround someone like Allen and I came to understand that these were false or had eroded over the years. I very rarely saw him anywhere near drugs (apart from prescription ones). If he drank alcohol — red wine was all I ever saw him drink — he’d get tipsy very quickly. When I first worked for him, I was intimidated somewhat by the legend but, after a few months, he was Allen and, rather than have an image of him reading ‘Howl’ or haranguing politicians, I have a picture of him in his kitchen drinking tea and preparing mangoes. When you’ve been to RadioShack with someone and laughed secretly at a man with a cockroach crawling around his hat, then the familiar overrides the legendary.

Did the biography change your view of Ginsberg in any way?

Yes. I developed a strong dislike of some of the people close to Allen — Neal Cassady in particular — and saw that Allen was more vulnerable than he had seemed when I worked for him. And that his behavior — the episodes of mental instability, his attraction to people who were addicts or (how shall I put it) psychologically challenged, his obsession with being part of the American literature canon (despite being a loose one, ka-boom-ching) and his championing of friends despite their blatant lack of talent — stemmed, to a large extent, from his childhood experiences.

How did you research the book?

First, I read the biographies already out there — Bill Morgan, Barry Miles, Michael Schumacher and Ed Sanders, correlating dates and places — Allen was in constant motion. I then read secondary material on the Beats, again Bill Morgan, James Campbell, Ann Charters, Joyce Johnson, Sam Kashner, John Tyrell and others. After that came selective reading of texts by and biographies of William S Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady, Gregory Corso, and others.

Once I’d established a timeline and a placeline, I read through the primary texts — the poems, the letters, the prose, the interviews, the journals, and listened to all available audio — and associated these with the chronological data. People who knew Allen were generous with their time; so I emailed or telephoned them and asked them questions about Allen.

I finally went back over what I had and added observations, criticism, personal reflection, and basically what sprung to mind as I was working.

Then — with the generous help of Peter Hale at the Ginsberg Trust — I chose photographs and illustrations to complement the timeline.

Were you conscious of not wanting to disappoint Ginsberg while writing it?

Yes, particularly with regard to style. Allen worked vigorously on everything and I wanted to do the same — with energy, honesty, precision, and humor. As an aside, I vehemently reject the ‘First thought, best thought’ philosophy attributed to Allen’s writing methodology (Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s phrase, not Keroauc’s, as it is sometimes claimed). Yes, Allen may have been spontaneous in his original compositions (as are a lot of writers) but he would then rewrite and edit until the text was how he wanted it.

How long did it take to write the book, start to finish?

Two years. It took about six months to research and a year to write, sitting at my desk in Chitose (Japan), staring out at the buildings, the mountains, the volcanoes, most of the year covered in snow, my big fat cat either curled behind my chair or on the table. I worked from 8 until 4 six days a week. Then six months to edit, get permissions and illustrations. In all, three years until it was published. I was lucky to have an understanding partner, Victoria, to give me the time and mindset.

Sarah Stodola is a freelance writer who blogs here and tweets here.

New York City, September 10, 2012

★★★★★ The ideal of the season. A flight of pigeons turned and turned, paper-white in the sun, up and away from Lincoln Center. A tiny figure, nearly hidden by bulky, suited bodies, crossed the plaza in a moving ring of backward-sprinting paparazzi and advancing teenagers. Whatever cleverness might have glimmered in chemical-green accents and accessories in the retail environment was gone under the plain, full light of nature. The color was a tiny dog yapping in the primeval forest, a Mountain Dew bottle on the Gulf Stream. A cloud passed over the sun, spreading equal shadow over the various zones of belonging and exclusion. Figures holding champagne flutes peered down from the terrace of Avery Fisher Hall, while behind their backs and above them the window glass caught the vastness of the whole moving sky.

The First Video That Meant Something To Me: Seona Dancing's "Bitter Heart"

Part of a series for the new Awl Music app.

For me it was “Bitter Heart” by Seona Dancing, feat. a slender, Bowiefied Ricky Gervais singing the lead vocal ca. 1984. Such a shock he was really quite lovely in that dandified way boys had about them in those long-ago days. I, then a callow goth, was partial to this exact varietal, and should certainly have been setting my turban at M. Gervais had the opportunity presented itself. At the Batcave in London or at the Camden Palace I accidentally went in the men’s room once to find the most ravishing sight, some fifteen boys crowded along a mirrored wall and messing with their eyeliner.

Even more interestingly, I fancy you can sense the hunger for recognition, an ambition to be seen and acknowledged, in those mascara’d eyes; that’s why the video has stayed with me. It’s a strangely touching comment on what performers are like, the lengths they will go to; the protean nature of ambition. (Plus the shadow-hammer guy? What the hell? What are they, in a coal mine? And fantasically incoherent, unmistakably 80s lyrics: My carven smiles // Revolt you in your torturous insecurities.)

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.

The Cost Of Being A Kid In A Classic Adventure Novel

A special after-school installment of Adjusted for Inflation, as part of this series about youth.

You probably haven’t been a kid for some years now. Maybe five years, or maybe many more. But whatever your age, there comes the moment of nostalgia sneaking up on you, and you remember that treehouse you had, or that clearing in the woods where all the kids played, which maybe you called something fanciful like Terabithia, or that playground with the monkey bars that served as the spaceship that everyone would compete to captain. Or maybe even bigger ventures, the running away from home, like Claudia and Nick in From The Mixed-Up Files Of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, or the summer camp trip that turned into an odyssey, maybe as sweeping as Sam Gribley’s in My Side of the Mountain.

So, as we once looked into the cost of making it as a young woman writer in New York, let’s look at the adventures and misadventures found in classic kids books, and how the economics of them compare, over time. We chose seven books (and yes, we had to omit many favorites). Each takes place in the U.S., and (with one young-adult exception) each is a kids book with a clear adventure, as opposed to, say, the day-to-day adventure that going to school can be, for a kid. We tried to space them over history, but we decided to stick to the past ninety years or so, and we also decided to avoid books with supernatural or sci-fi elements, as the question of how much a wrinkle in time might cost seemed an unanswerable question.

Of course where possible we will compare actual dollar amounts with same amount converted in 2012 dollars, but, for this installment, we are also interested in the general topic of how money informed these stories of escape or crime-solving or adventure.

***

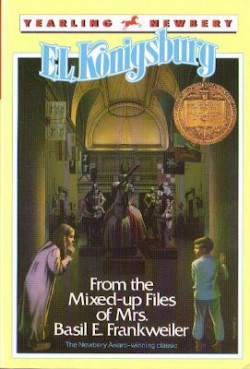

THE BOOK: From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E. L. Konigsburg

YEAR: 1967

THE (MIS)ADVENTURE: Brother and sister run away and live in Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Let’s start with a real crowd-pleaser. The first line: “Claudia knew that she could never pull off the old-fashioned kind of running away.” The book is the story of a caper. Children of a comfortable Greenwich family Claudia and Jamie Kincaid, sixth-grader and third grader respectively, gather their financing, hop a commuter train and camp out in the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a week. With Claudia as the brains of the operation, and Jamie as the exchequer, they pull it off. And by camp out, we do mean camp out — evading security in the mornings and evenings, choosing a canopied bed in the Renaissance wing to sleep in, and using a (now gone) fountain in the museum restaurant for bathing.

This is a kids book with a very clearly delineated backdrop of money issues, as part of the adventure of squatting in the Met is the cost of it. The book is so attentive that it’d be possible to construct a day-to-day chart of the kids’ expenses, but here we’ll stick to a few examples. The two live primarily off of Jamie’s savings, twenty-four dollars and forty-three cents (which would be $167.58 now), which he acquired not through his allowance ($.25 a week, or $1.71 now) but through cheating his buddy at War playing for pennies per card. That’s not a small sum for two kids, even for a lost week in Gotham. Breakfasts were largely eaten at the Automat (this is very much a New York City book), and breakfast on the second day, cereal and pineapple juice for Claudia and a cheese sandwich and coffee for Jamie, ran fifty cents apiece, or $3.43 adjusted. And they even manage to wash the clothes they have, as these are two kids who understand the relative importance of cleanliness. It cost a quarter for the wash, ten cents for the soap and twenty cents for twenty minutes of dryer time — fifty-five cents, or $3.77 converted.

Breakfasted for fifty cents apiece in 1967 ($3.43 adjusted).

Illustration by E.L. Konigsburg.

And Jamie is not only the treasurer for the trip, but he is genuinely obsessed with money, as evidenced by his pre-runaway stash. During days at the museum, they blend in with school field trips to snag a free lunch. At one school lecture in the Egyptian wing, Jamie asks: “How much did it cost to become a mummy?” And even Claudia admits, near the end of their adventure, as their quest to determine the provenance of a Michelangelo statue (bought at an auction for $225 dollars, or $1,543.37 converted) leads them to the estate of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, the narrator of the story and seller of the statue, “There’s something nice and safe about having money.”

That is an apt sentiment, as, even though the kids pinch pennies as they go through their week, they are from a decidedly upper-middle-class existence, to the extent that we find out that, surprise! Mrs. Frankweiler’s staid lawyer, Saxonberg, is the grandfather of Claudia and Jamie. The dangers that the kids face, of being discovered and returned to their parents, are not very dangerous. Claudia and Jamie have it pretty sweet back at home, as sympathetic as we may be to their quest. We can imagine large parts of America in that time period would have a hard time seeing themselves in the story. This is not to take away from the appeal of the book, or from what the book says about adventures and why we are drawn to them. But, as focused on money as Jamie, and the book, is, the world of the book is a world where expense is ultimately not an issue.

But why did they run away? On Jamie’s part, because Claudia convinced him, and because it was an adventure. On Claudia’s part, she’s on a quest for some greater purpose. “I didn’t run away to come home the same.” And later she adds, “And I don’t want it to be over until I’m sure I’ve had enough.” There was nothing wrong with life at home other than a few kid-like complaints of chores; this was not a dystopian family that sometimes spurs the action in runaway stories. Claudia is looking for an epiphany. She doesn’t want to end up a cartoon in a cartoon graveyard, as it were. And it’s Mrs. Frankweiler, at her home in Farmington, that provides the gentle answer:

The adventure is over. Everything gets over, and nothing is ever the same. Except the part you carry with you. It’s the same as going on a vacation. Some people spend all their time on a vacation taking pictures so that when they get home they can show their friends evidence that they had a good time. they don’t pause to let the vacation enter inside of them and take that home.

Which is some pretty prescient advice for 1967, no matter one’s views on the role of money in one’s life.

THE BOOK: Bridge To Terabithia by Katherine Paterson

YEAR: 1977

THE (MIS)ADVENTURE: City girl moves in next to local boy, they become best friends, conspire to make us all cry our eyes out.

This one, as you’ll remember, is a tearjerker. Jess Aarons is entering the fifth grade of Lark Creek Elementary, in a rural section of Virginia. His family has a cow named Bessie that is his responsibility to milk, and he has two older sisters and two younger sisters. A girl moves in next door. Her name’s Leslie, and she’s from Washington D.C. She dresses funny for a girl in Lark Creek Elementary, tomboy-ish, and she has short hair. And she quickly becomes Jess’ best friend. She does not fit in. She disregards the unwritten rules of the school, with an attitude that passes for a pre-adolescent version of cosmopolitan. And she doesn’t enjoy it there very much.

She and Jess gel, and create a sort of clubhouse/fort across a creek bad and on the edge of the woods a short walk from their houses. There they establish the Land of Terabithia, an imaginary kingdom that they rule over as King and Queen. “Like God in the Bible, they looked at what they had made and found it good.” This is the adventure they have, Jess and Leslie, creating a space that inures them from the dull reality and small-minded tedium of Lark Creek Elementary.

A pair of boy’s jeans, $10.99 in 1977 ($41.56 adjusted); a pair of girl’s jeans, $11.99 ($45.33). Illustration by Donna Diamond.

But the adventure doesn’t last. Leslie dies, drowns in the swollen creek when Jess is away. That’s the part you shouldn’t read on the subway. What follows is as clear-eyed a depiction of grief you’ll find, which is finally thankfully broken when Jess takes his kid sister May Beth, the pest, down across a bridge he had quickly built across the creek, to be the new Queen of Terabithia.

A Bridge To Terabithia is a harrowing story of the adventure gone wrong, or, more accurately, cruelly cut short, but it’s also a document of a certain sociological shift that occurred during the 70s. Jess’ father is a laborer. At the beginning of the book, he’s driving back and forth to D.C. every day, as there are no jobs nearer to home. And the Aaronses are hard-pressed for cash. For a back-to-school shopping trip, the mother can only (grudgingly) part with five dollars for the two big sisters to shop for back to school supplies (which would be $18.90 now). Christmas is not a lavish affair for the Aarons. They are solidly working class.

But Leslie’s family, the Burkes, are members of what might be called the Creative Class. Mom and Dad (addressed by their daughter by their first names, Bill and Judy, as thick a signifier of the 70s as anything) both write for a living, and the reason that they have moved into the house down the hill from the Aaronses is, according to Leslie, because they are “reassessing their value structure.” They do not have a TV. But they aren’t hippies. Jess’ favorite teacher, Miss Edmunds, is the hippie. The Burkes are nascent Yuppies, though the term hadn’t been coined yet. They move to get their only daughter out of the city, away from the television, and into a more humble existence with trees and dirt and that sort of thing.

The area in which this takes place is not hillbilly-rural — shoelessness occurs by choice, and there are shopping centers in the neighboring towns that are the perennial target of the two older Aaron sisters. This is not a country mouse/city mouse story; little is stereotypical in this book. But it does feature a slow-motion collision of economic circumstance, as the child of the hard-scrabble meets the child of the flight from affluence. The Aaronses are defined by their lack and want of money (Jess’ dad is laid off right before the Terrible Day), while the Burkes are defined by their heedlessness of their well-to-do status.

A boy’s knit shirt was $5.99 in 1977 ($22.65 adjusted).

Illustration by Donna Diamond.

And interestingly enough, it is the Burkes who move away from the area as the book comes to its conclusion, and the Aaronses, and Jess, that stay. Looking at the book purely from a socioeconomic viewpoint (while admittedly wiping tears from eyes), the story is one of looking up at the Creative Class, as they sweep in and out of town — a brief and temporary gentrification.

THE BOOK: Harriet The Spy by Louise Fitzhugh

YEAR: 1964

THE (MIS)ADVENTURE: Idiosyncratic grade-schooler who imagines herself a spy navigates social landscape.

In this kids book, the caper is Harriet herself. This is no Journey of the Hero in the Joseph Campbell sense; Harriet is a spy, almost genetically, documenting everything she encounters in her notebook in the early 60s Upper West Side of Manhattan. The obstacles that she must overcome she creates herself, or are the obstacles of a generic childhood, like the departure of her nurse/babysitter, or the school-kids banding against her because of the impolite observations she makes of them in her notebooks, or plotting to avoid the dance class her parents want her to go to. This is more the Journey of the Average Kid.

But there is adventure to be had, as Harriet is not a spy out of pique:

“I want to know everything, everything,” screeched Harriet suddenly, lying back and bouncing up and down on the bed. “Everything in the world, everything, everything. I will be a spy and know everything.”

And so Harriet not only scribbles observations of the day-to-day happenings, but also has a spy route that she lights out on every day after school — the Italian family that runs the grocery, a be-catted model-maker, a wealthy couple. It would probably be labeled a pathology today, but Harriet is unable to resist documenting her life on an as-it-happens basis.

Harriet has spy clothes, a hoodie and jeans, and a spy kit: a flashlight, a water canteen and a “boy scout knife.” But the primary tool of Harriet the Spy is the notebook, which must be at her side at all times. In 1964, the retail price of the Big Chief school tablet was 39¢ for forty pages (or $2.88 now, which seems like a lot?). Harriet is a sixth grader, so presumably her kit is supplied by Mom and Dad.

Big Chief school tablet, 39 cents in 1964 ($2.88 adjusted). Illustration by Louise Fitzhugh.

And remember that this story is set in the Upper East Side in the early 60s. Her family lives in a town house on East Eighty-Seventh Street, and they have a cook and a maid. The backdrop is New York City, so the characters in the background come from all classes, but the kids are all the children of what would be considered affluence, although not outright wealth — note Harriet’s best friend Sport, whose dad is a freelance writer waiting for his ship to come in — but of station enough, in the case of Harriet’s family, to afford the services of a nurse and a cook. And Harriet does have spending money: one of her spy stops is the soda fountain, where she has a chocolate egg cream and eavesdrop. The egg cream costs 12¢, or 88¢ adjusted.

As a sidebar, when her school offers her the job of writing the sixth-grade portion of the newspaper, Fitzhugh describes the moment when Harriet reads her first column: “She read her own printed words with a mixture of horror and joy.” The enduring popularity of Harriet The Spy is no mystery, as it is the story, one way or the other, of every media professional alive everywhere.

THE BOOK: Tiger Eyes by Judy Blume

YEAR: 1981

THE (MIS)ADVENTURE: After her dad is murdered, a girl and her family relocate to Los Alamos, mourn.

As she details in the afterword, Judy Blume lost her own father at a young age, and she was looking to write a book showing how the lives of kids can be affected not by violence, but by tragic and senseless loss. Davey Wexler’s father, proprietor of a 7–11 in Atlantic City, is shot and killed for fifty dollars ($126.02 adjusted), so the Wexler family, Davey and her mom and little brother, move to Los Alamos, New Mexico, to live with an aunt and uncle for what turns out to be a year.

On one level, the book is a snapshot of the life of a high-schooler in the early 80s. Davey, a sophomore, interns as a candy striper, and makes local friends, has a double date involving a bottle of vodka in which the boys scrape together eight dollars and sixty-four cents ($21.78 converted) for pizza and sodas. She has exactly $74.68 saved up from her summer job (which adjusts to $188.22 now), and she spends $32.50 of that (or $81.91 now) of that on a pair of hiking boots, which she uses to meet her mysterious quasi-boyfriend “Wolf,” who is also undergoing turmoil as his father is dying of cancer. An allowance is discussed with her aunt, who slips her a ten as spending money for her first day of school in Los Alamos ($25.20 converted). Davey’s not wanting; she’s spending what your average teen would be spending.

But the book is unique in the books selected as it does deal with the concept of the family finances. Part of the reason they move is that the father left no will, and no life insurance payout. In addition to the wrenching grief that consumes everyone (primarily, and not surprisingly, Davey’s mom), there is the uncertainty of what to do next, how to put the food on the table, and the aunt and uncle generously offer to take that concern off the mom’s shoulders. No dollar figures are mentioned, but, on top of the loss of the father, it’s finances that cause the Wexlers to spend a school year in Los Alamos, with the aunt and uncle, relatively more affluent than the Wexlers, with their expansive house and the side of beef they buy each year and their new pasta maker. It’s a telling subject, as how often do the choices made by the parents, choices informed by money, affect the lives of the children in ways that only reveal themselves in retrospect? In the real world: often.

Of course Tiger Eyes is not an economic treatise, but rather an unblinking story of what it’s like when the worst thing imaginable happens. (Like many of these books, it was adapted into a movie, in this case one released this year .) It tricks you into thinking that this is a romance, that Wolf will be the young man to pull Davey from her grief, but it’s not that cut and dry, and more chaste than expected. The dad is the unspoken character, both in the ways that he leaves the family unprepared for his passing, and in the ways that he is missed. Among the Christmas shopping Davey does she buys a five-wicked candle, the kind her dad would have liked, for $3.95 ($9.96 now), and burns it on Christmas night, alone in her room.

THE BOOK: The Boxcar Children by Gertrude Chandler Warren

YEAR: 1924

THE (MIS)ADVENTURE Four orphaned siblings live in boxcar; are resourceful then lucky.

The easiest way to demonstrate how different The Boxcar Children is from the other titles is the end:

“I hope not, my dear,” said Mr. Alden. “We’ll all live happily ever after.”

And so they did.

Not that all of the other books opted out of the happy ending, but none invoked the happy ending by saying it out loud. Truth is, as this book is older than all the others, it’s the most alien to kids books of today. Kids were kids longer back then (or at least the then-current literature so assumed), and a See Dick Run tone of the book runs through the book.

The same goes for the plot, which plows straight ahead like a steamroller. The kids — Benny, Violet, Jessie and Henry (in ascending order of age) — are roughing it, as their parents are dead and they are scared of their grandfather. In no time, they’ve found an empty boxcar in the woods, next to a creek for water and a junkyard for Deus Ex Machina. In less time, they are prosperous and comfortable (and eerily cheerful for orphans). And in even less time, they are set for life. They even get a dog in the process. The obstacles to overcome are purely implied.

Money is almost the fifth Alden child. While much of the children’s experience resembles a mash-up of Freeganism and “Gilligan’s Island”-style ingenuity — a ladle made from a cup, a stick and some wire! a pencil fashioned from a charred stick! — it’s the economic transactions, the purchases and barter, the fuel the carefree success of the kids. They (mysteriously) start out with four bucks in their pocket (or $53.59 adjusted). The kindly doctor that the oldest Alden, Henry, does odd jobs for pays the young man a dollar for each morning or afternoon of services performed (or $13.40 adjusted). And for winning a footrace at the Silver Field Day, Henry wins a silver cup and a prize of twenty-five dollars (or $334.95 adjusted). And the expenses of being Orphan Family Robinson? Negligible. What they pay for is food: loaves of bread, some milk. A pound of bread in 1924 sold for nine cents ($1.21 now), and a half-gallon of milk for twenty-eight cents (a shocking $3.75 now). Expenses were not exceeding revenue by any stretch of the imagination.

One pound of bread, 9 cents in 1924 ($1.21 now); a half-gallon of milk for 28 cents ($3.75) in 1942. Illustration by L. Kate Deal.

This falls in line with the casual self-reliance paraded through the book by Warren. The children: they like to work. Picking cherries for the doctor, they say to themselves how they love to pick cherries. Damming the creek to make a bathtub, they say to themselves how they love to build dams. And amidst this cheerful industry good fortune falls on them like hail. Even the scary grandfather they are trying to run away from turns out to be a kindly, younger man who can afford to pay a $5,000 ($66,989) reward for their safe return.

In the stiff formality of childhood presented in The Boxcar Children, where the boys work and provide and the girls cook and clean, economics are purely a function of moral character. Compare and contrast this with Tiger Eyes, published fifty-seven years later.

THE BOOK: Scat by Carl Hiaasen

YEAR: 2009

THE (MIS)ADVENTURE: Middle-school best friends find themselves in the plot of a Carl Hiaasen novel, avoid bumbling bad guys, save both the Everglades and endangered panther.

Just as The Boxcar Children is emblematic of a more innocent time in kids literature, Scat is a clear example of how comparatively grown-up kids books are these days. Scat. The book is indistinguishable from Hiaasen’s adult, genre fiction but for the fact that the story is told from the POV from the kids, Nick and Marta, and there is no swearing, boozing or sexing. The plot is as giddily absurd as the standard Hiassen, the bad guys as quirky and ultimately bumbling, and the good guys deeply concerned with Florida and its natural wonders. Two characters from earlier adult novels are even featured, including Twilly Spree, the protagonist of Sick Puppy.

Nick and Marta stumble into investigating as reviled teacher Mrs. Starch goes missing after a field trip to Black Vine Swamp, and spooky loner and fellow student Duane “Smoke” Scrod Jr. is suspected. Nick’s and Marta’s casual curiosity leads them into a web of intrigue, uncovering a plot by Red Diamond Energy Corporation to hit oil on government land, the same land where Twilly Spree is trying to reunite a panther kitten with its mama.

Little shrift is given in the book to personal finance issues that kids may face today. Both Nick and Marta are solidly middle class, and even though they (and Smoke) attend a private school, Hiaasen takes pains to note that the school has fallen on hard times and has loosened its enrollment standards. About the only time that some financial concern is shown is when Twilly leads the kids through the swamp, and Marta worries that her brand-new Converses would be ruined. (If they were, say, the Trail Runner, a $47.00 expense.) Allowances and discretionary income are not at the front of the minds of Nick and Marta.

But at the same time, Hiassen does paint a picture of how southern Florida is at the mercy of a confluence of class issues. While the kids are middle class, Smoke’s grandmother is wealthy, and it’s her fortune that guarantees Smoke a slot at the school. And of course money is the motivating factor of the principals of Red Diamond — not for the millions an oil strike would bring, but rather the millions the government would pay for drilling not to happen in the Everglades. In this sense, the economics of the book are as grown-up as the plot itself, as what’s at stake is not how much Nick’s allowance is, but how the native flora and fauna sometimes collide with the financial interests of the speculators and developers.

THE BOOK: My Side Of The Mountain by Jean Craighead George

YEAR: 1959

THE (MIS)ADVENTURE: New York teen lights out for the wilderness, rightfully earns nickname Thoreau.

“Any normal red-blooded American boy wants to live in a tree house and trap his own food. They just don’t do it, that’s all,” says Sam Gribley, explaining his journey. Gribley is the oldest of a large Manhattan family, who heads for the mountains of the Catskills (with his father’s blessings). Over the course of the book, he learns to be entirely self-sufficient, burning a “house” into the trunk of a large tree, fishing, trapping and foraging for food, bathing in a stream. He even finds himself a baby falcon, which he names Frightful and trains to hunt for him. At times it reads like more of a how-to than a novel, as Sam meticulously narrates how to make a fishhook, what plants are good for eating, how to tan a deer hide. While it is easily read as an answer to Thoreau or a precursor to Edward Abbey (an author copiously mentioned in Scat (apt, as Sam Gribley could easily grow up to be Twilly Spree), George is clearly a committed naturalist. Another reason for Sam’s year as a mountain man: “The main reason is that I don’t like to be dependent, particularly on electricity, rails, steam, oil, coal, machines, and all those things that can go wrong.”

Price of baby falcon: N.A.

Illustration by Jean Craighead George.

Sam heads out with a penknife, a ball of cord, an axe, a flint and steel and forty dollars that he had saved selling magazine subscriptions. That $40 then would be $314.92, by the way, which is not a modest sum. But the fascinating thing is that the initial mention of that forty dollars is practically the only time that money is mentioned. Sam does buy a train ticket to get most of the way there (a mountain near Delhi, New York), but that’s it. Every other item, the food, the clothes, even the birch bark that he writes on with an ash pencil, he either makes himself or forages. It is a story of utter self-reliance.

But it’s not even a survival story. All travails are cheerful. And Sam is by no means alone. On top of the animal friends he makes — a weasel he calls The Baron, a raccoon he names Jesse Coon James — Sam has a steady stream of visitors. A little old lady finds him while picking wild strawberries, a college professor befriends him while lost on a hike. There is not a strong swipe of loneliness in the book. Sam is not getting away from it all; he’s recreating his world in the wilderness. The world he creates is so compelling that his entire family comes up to live with him for a summer at the end of a book.

It’s a patient, straightforward work. The elements of natural world are described lovingly, particularly the culinary creations that Sam toils over (Christmas dinner: blackened venison steaks, mashed cattail tubers with mushrooms and dogtooth violet bulbs with acorn gravy, and stewed honey locust beans with hickory nuts. Right?). What sets this book apart from the others included is that it completely sidesteps any sociological/economic issues, and deliberately so. It posits a world without money, a life led entirely without commerce. It’s a Utopian work.

***

It’s perhaps unfair to directly compare all of these books. Some, like The Boxcar Children, are aimed at the younger end of the Juvenile market, and others lean toward older kids or, like Tiger Eyes have a Young Adult classification. And naturally, there are hundreds more kids books that have much to say on these issues. For that reason, it’s tough to pull anything resembling a trend out of this. It could be fair to say that the ways that kids books dealt with money issues becomes more sophisticated over time, but then again the kids books themselves become more sophisticated as well. It’s interesting that the books of the 60s, namely Harriet the Spy and Mixed-Up Files, come from a more upper-middle- to upper-class perspective, but then again they are both set in the more well-off precincts of Gotham.

One thing is clear though: nearly every single of these books (sorry, Boxcar Children) is worth the re-read, or the first-time read if any are unfamiliar to you. There is a heart of absurdism to Harriet, and Scat is as satisfying as anything else Hiaasen has written. These are wonderful books, and you would not be wasting your time to augment the reading of the Hot New Thing with a re-read of some of the books you grew up with — the Newberry Medal is for real.

Maybe the reason why it’s so easy to suss out socio-economic facets of these kids books is that they’re books, just like boring old grown-up books, and maybe kids aren’t as naïve to the ways of the world as is assumed. But then you already knew that even if you forgot, having been a kid yourself, once upon a time.

Previously: What It Cost Eight Women Writers To Make It In New York