Hammer, "Man Ray"

We need to talk about how you’re feeling right now.

Let’s say you’re someone who has spent a large part of your life telling people that everything is terrible. Day in, day out, your theme is the same: It’s all meaningless, you’re being deceived and deceiving yourself in turn, and things are only getting worse. No matter how many people shake their heads and reject you, call you names behind your back or generally do anything to ensure that they don’t need to deal with the substance of your message, you continue to point out how horrible it all is. And then, finally, something happens to make the evidence so incontrovertible that even your most willfully deluded detractors are forced to concede that you have been correct all along. You’d think you’d be happy, that your vindication would bring some sort of satisfaction, but I am sorry to say this is not the case: You people are bumming me out. What I expected was that you would all sheepishly acknowledge that I have indeed been right and then gradually go back to your lives of kidding yourselves about the possibility of bright spots. (I did not expect any thank yous or let me buy you a drinks — if there’s anything that people hate more than realizing that they’ve been wrong, it’s the face of the person who has been right the whole time, especially when they’ve been so dismissive of him and his quiet, justified insistence.) I figured by now you’d have absorbed the knowledge of our intolerable existence and your brain would have resumed doing that thing where it fools you into pretending it will all work out okay. But no! You’re all as bad as me, every second, and it’s too much! What do you think I’m here for? It’s not just to be right about everything, although that is indeed part of my purpose. I am also here to bear the burdens of your suffering so that you can go on with your lives unimpeded by the awful sorrows I carry around on my bent and broken shoulders. We can’t all be me all the time: It puts things out of balance. It disturbs the order of life. It’s a big fucking drag. Look, there’s no hope for me: I exist to observe the agony, endure the ache and then die. You have hope. It’s what keeps you going. You wouldn’t get out of bed in the morning without it. Believe me, I understand: Everything sucks. I’m the guy who wrote that song in the first place. But I need you to act like everything sucks a little less than it does, because it’s too much to take for everyone with all of you always being this down. I’ll handle the anguish, you please just get out there and live like it’s all going to be okay, okay? Thank you. Now here’s some music. Start acting as if you like it again.

New York City, April 2, 2017

★★★★ The boys kept their coats on inside the church, but right afterward the sun outside was fully warm. The video ads on the bus shelters were faded like forgotten out-of-date posters. Cars and taxis were mostly too unwashed to be blinding. Adults imparted lessons to children about exponents or Starbucks as they strolled. Little white shreds and puffs of cloud floated over the afternoon. Walking down the long slope toward the river, the five-year-old in his track pants and athletic hoodie tried to claim it was as hot as summer. That was absurd, but the walk back uphill in the sun was more than a grownup’s light sweater and light jacket were really suited for. The tiny clouds below the wash of sunset were neatly half purple and half pink.

Prince's Female Mirrors

The Svengali and his muse.

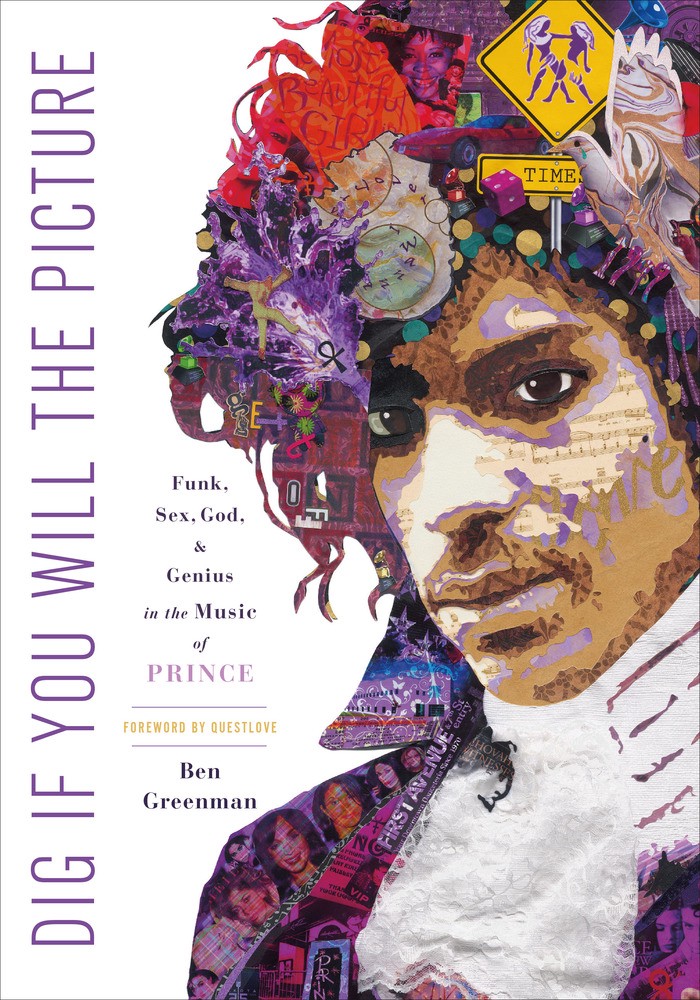

The following is excerpted from Ben Greenman’s forthcoming book-length study of Prince, Dig If You Will The Picture (Henry Holt), set to be published on April 11.

In pop music, female artists are often controlled by male artists — they are given songs to sing, costumes to wear, sometimes even new names to replace their real names. There’s a long tradition of this, or rather, two of them: the Pygmalion tradition on one hand and the Svengali tradition on the other. Pygmalion stories, which began in Ovid and crystallized into their modern formulation in George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 comedy of the same name, usually end with the older male figure falling in love with his protégée. Svengali stories, rooted in George du Maurier’s 1895 novel Trilby, tended to be more exploitative and predatory: du Maurier’s own illustrations depicted the character as a spider in a web, trapping and devouring his prey. Historically, the music industry has lent itself more to the latter model. Rebecca Haithcoat, writing in Vice Media’s Broadly just a few weeks before Prince died, explored the history of the male Svengali in pop music, from Phil Spector to Kim Fowley, with a special emphasis on the economics of the arrangement. Women were permitted to write and perform songs, while men tended to occupy producer roles, in large part because production was needed (and compensated) whether or not songs were released. Similarly, upward mobility was distributed unevenly among the sexes; women had plenty of male mentors (older industry figures who helped them find their way to more work) but not nearly as many male sponsors (older industry figures who taught those younger women how to create work themselves). In these terms, Prince was a Svengali, though his special relationship with female identity ensured that he was just as snared in the web.

Backstage at the American Music Awards, he met a young model and actress named Denise Matthews. Matthews, in her early twenties, had been born on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, the product of an ethnic crazy quilt that included Afro-Canadian, Native American, Hawaiian, Polish, German, and Jewish blood. She had gone to New York to model, but she was too short, and an agent suggested Los Angeles and acting roles instead. She found some, including a small part in Terror Train (a slasher film set aboard a moving train that starred Jamie Lee Curtis) and a larger one in Tanya’s Island (a romantic adventure, of a sort, about a castaway juggling relationships with both her brother and an ape-man). In both films, Matthews was billed as “D. D. Winters.” In neither film was she especially memorable.

But she made an impression on Prince. The two of them began a relationship, and when he returned to Minneapolis, he invited her to come stay with him. Once she arrived, he began to involve her in a new idea he had — a highly sexualized girl group performing songs he would create especially for them. The initial incarnation of the group, called the Hookers, was built around Susan Moonsie, a friend of Prince’s from high school. The Hookers petered out around the time of Controversy, but Prince revisited the concept with Denise, who he felt would be a perfect frontwoman for the band. He tried to convince her to change her name to Vagina. She refused, understandably. They compromised on Vanity.

The name had at least two meanings, both perfect: Prince liked to think of Vanity as his female mirror image, and she was also about to become the center of his first true vanity project (though you could make the argument that Morris Day, with his mirror, was also all about vanity). Vanity, Susan Moonsie, and a third singer, Brenda Bennett, entered the recording studio in March of 1982 to add vocals to a set of tracks that Prince had already prepared. Five months later, Vanity 6 released its debut. “Nasty Girl,” the opening song, established the formula: spare synthpop grooves, mostly friendly, with salacious lyrics and vocals that were more coy than powerful. “Do you think I’m a nasty girl?” Vanity asked, and answered a few lines later: “I need seven inches or more/ Get it up, get it up — I can’t wait anymore.”* Elsewhere on the record, Prince gave the band more outré electronics (“Drive Me Wild,” “Make-Up”), risqué songs (“Bite the Beat,” a celebration of oral sex which could have been handed off to Blondie or the Go-Go’s), and relatively innocent songs with risqué titles (“Wet Dream”). The ballad “3 x 2 = 6” had an attractive melody, but it exposed Vanity’s limitations as a vocalist. The funkiest, funniest moment was the Time-like “If a Girl Answers (Don’t Hang Up),” a skit-song combo in which Vanity tangled with the new girlfriend of an ex (played, hilariously and unconvincingly, by Prince).

Vanity 6 ran its course — or rather, ran off course. Vanity was cast as the romantic lead in Purple Rain but departed before shooting started. Replacement auditions for the film were hastily arranged. The part went to Patricia Kotero, a Mexican-American model and actress who had had appeared in various television shows and a few music videos, including Ray Parker Jr.’s “The Other Woman.” Prince renamed her Apollonia — this time, he only had to look as far as her middle name — and cast her in both the film and a new version of Vanity 6. Apollonia 6 featured mostly Kotero and Brenda Bennett, along with backing vocals by Lisa Coleman and Jill Jones. Though Apollonia was a better singer than Vanity, the music had little of the punkish insistence of its antecedent. The songs were more fully realized, which ironically worked to their disadvantage — mostly they just sounded like less energetic Prince songs, and in fact several tracks demoed by Apollonia 6 and left off the album ultimately entered the Prince canon via other routes: “Manic Monday” (which ended up with the Bangles), “The Glamorous Life” (which found a home with Sheila E.), and “17 Days” (which became the B side of “When Doves Cry”). The two keepers were “Sex Shooter,” a close cousin of “17 Days” that the band performed onscreen in Purple Rain, and “Happy Birthday, Mr. Christian,” which reversed the plot of the Police’s “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” and added a deadbeat-dad twist: Mr. Christian, the high school principal, impregnated a student but wouldn’t support her and her child. Apollonia left after the band’s sole album.

Excerpted from DIG IF YOU WILL THE PICTURE by Ben Greenman, published by HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY, LLC. Copyright © 2017 by Ben Greenman. All rights reserved.

There Is Definitely Crying In Baseball

I Watch Baseball Mostly For The Butts

And other unsolicited advice.

“My boyfriend is pretty into baseball. What should I be looking for to make these games less laborious?” — Not a Fan Stan

If you didn’t grow up with baseball, it can be pretty boring. It’s boring anyway, even if you did grow up with it. It’s a sport that was designed for watching while eating hot dogs and drinking beer. Including by the players. Maybe the only sport with more standing around and less action is curling. Pitchers take forever between pitches, batters jump in and out of the batters’ box. Don’t even get me started on how long replay decisions take. It’s 3 to 5 hours of your life you’ll never have back. Like most sports I enjoy, you can take a nap in the middle and not miss much. But without it I am a shell-less snail, dragging my gross body back and forth, leaving only a trail of goo.

There are plenty of good reasons to get into baseball. Everyone gets a daily chance at redemption. Yesterday’s low-down dog can become tomorrow’s top dog. Baseball is a much fairer universe than the one we normally live in. Sure, there are a lot of commercials. But if you hit the ball once a while you’re a star. Pretty good gig if you can get it. And although only a handful of us ever get to play baseball, we can always imagine ourselves playing. Are you a little tubby? No problem, tubby is good. In what sport outside of Sumo is being tubby any good? None of them. Just baseball. And hot dog eating contests.

Surely, there are better ways to spend a Sunday night. Like, reading a good book. Oh yeah? Well baseball is a game that you can read a few chapters of a good book during. Just kind of poke your head up when you hear the undeniable sound of the bat on the ball. Or the ball in the glove. Stephen King brings books to Red Sox games all the time, just in case there’s a particular lull in the action. Great baseball books written by Halberstam or Roger Angell are almost as good as watching a live game. If you hear the crowd go crazy, put a bookmark in it.

I’m a big fan of butts. Big butts. Little butts. Butts of any kind. Most people have one. And there’s something about a baseball uniform with its stretchy pajama pants that just kind of show them off better than anything this side of yoga pants. From behind, everyone’s butts look good. It’s just when they turn around that you become less interested. You can pretend anyone looks attractive from behind. Most of the time we get to check out the pitcher’s butt on TV. There are some pitchers with long, well-conditioned hair. You can pretend they are Fabio or Jennifer Aniston. I have imagined both, either, same difference.

I don’t generally like to experience human emotions. In my own life, I like to push them as far down into myself as possible. Baseball brings all these emotions up to the surface, like a mento in a Diet Coke. I’ve cried more watching baseball games than at any other time in my life except prom night. Watching a parent play catch with a kid will get me every time. When the Red Sox and Cubs won the World Series, I cried. What else could make me cry? Possibly the Mets winning. Maybe the Brewers. Possibly the Mariners. If they ever bring the Montreal Expos back, I will cry. I am crying a little right now. I am getting kind of soft in my old age.

So, Stan, you may not like baseball. And there may be very little of sports you find appealing whatsoever. But everybody likes winning money. And gambling on things makes everything more fun. Gambling on baseball is tricky business. Betting lines are based almost exclusively on the starting pitchers. Early in the year especially, they’re only going to pitch a few innings. Select an amount of money you wouldn’t like to lose. Find a way to wager that on a baseball team of your choosing. You will become a very excited fan of baseball.

You can also join a Fantasy Baseball league. They have daily games and year-long leagues. You will start having opinions about players like Randal Grichuk of the St. Louis Cardinals. They will be like your pretend buddies. Or enemies. Life is essentially meaningless and the things we do we do to distract ourselves from the fact that we won’t exist here for very long at all. Maybe death is great. No one is complaining about being dead. Maybe they miss the baseball. But most likely dead people are all just hiding and at some point they will all come out and scare the shit out of us. You will know where to find me. In New Jersey, watching baseball.

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works at a bookstore.

Has Big Dogs Joined The Resistance?

Woof.

If you like dogs and toxic masculinity, you may be familiar with Big Dogs Sportswear. A popular brand of shitty graphic tees from the ’90s, their shirts featured a large, angry, black and white dog of ambiguous parentage (Was it a Newfoundland? A fat border collie?) burping and barbecuing and yelling. Big Dogs loved Beer, Hamburgers, and Sports, in that order. They resented Wives. They had enormous dog-muscles and wore sunglasses — when they were not wearing sunglasses they had blank and frightening eyes.

Though they once seemed indomitable, as the twenty-first century wore on, their empire dwindled. Big Dogs is now down to seven stores but they’ve managed to survive as a subsidiary of The Walking Company — a mall chain marketed towards my mom that offers 345 different kinds of clogs. As Jonny Coleman observed last year in his history of the “D-shirt,” or “douchebag shirt,” for MEL Magazine’s newsletter, the Big Dogs of the new millennium has embraced “a broader, more generic version of Internet-friendly ersatz and vaguely threatening catchphrases” with debatable success. “I didn’t like you 20 years ago and I STILL don’t!” yells a dog on one shirt, as he bites through a plank labelled FaceBARK. “Stop Staring at my twitters,” reads the text on another. On either side, chicks — baby chickens, not women — stand in front of desktop computers, wearing matching sunglasses and smiling coyly. On yet another shirt, a bartending dog appears to take credit for the death of Osama Bin Laden.

As a rule, Big Dogs are indiscriminately angry but not explicitly political. Big Dogs are not calculating enough for politics — if there is a Big Dogs ethos it is erratic and larcenous. Big Dogs are always trying to sell you a stolen TV they picked up in Bayonne. Big Dogs would probably enjoy 4Chan but they are not really internet savvy enough to participate. Big Dogs post insane music videos about the Cajun Navy on your Facebook wall a couple times a year and write “HAVE A BLESSED DAY.”

All of which is to say, they seemed like they would be receptive to many of Trump’s campaign promises. “Drain the Swamp.” Yes, you could see Big Dogs nodding. Yes, it needs to be drained. He was Big Dogs made flesh — a loud, infantilized man with gross skin and outsized power. I looked at their website a couple weeks ago expecting jubilant, pro-Trump propaganda and was surprised to find instead a new shirt — a dog dressed up as a founding father, framed against an American Flag. “I Can Not Tell an Alternative Fact,” read the script below. Scroll down and you’ll see another — a dog scowling in a polo under the words “I Pay More Taxes Than Donald Trump.”

“No, we have no political stance,” said Steve Dawson, Big Dog’s sportswear director, when asked if they had joined the resistance. “We’re politically incorrect, that’s our political stance.”

Okay, fine, so Big Dogs does not have your back. Big Dogs exist only in opposition, they stand for nothing and no one except a man’s right to stew in his own filth. But if there is a summation of the Big Dogs self-image it’s their most well known shirt, a gray tee that reads, “IF YOU CAN’T RUN WITH THE BIG DOGS, Stay on the Porch!” A man and a woman sit on the steps of a white, colonial-style porch, gazing admiringly at a huge running dog that appears to be about to crush them. Off the Porch is implied to be a place full of danger and terrible beauty reserved for the extraordinarily brave or the extraordinarily bloodthirsty. On the Porch is a place of relative safety and quiet tragedy; missed opportunity, impotence, captivity, and cowardice.

Most politicians stay on The Porch. Lincoln was Off the Porch. Nixon, terrified to step Off the Porch, had to tunnel away from it underground. Jimmy Carter tripped Off the Porch and was ripped to pieces by wild animals immediately. Reagan wanted people to think he was On the Porch, but ran wildly Off the Porch, blood dripping from his jaws. Obama kept getting thrown back onto The Porch, but fought valiantly. Bill Clinton was perhaps the only president entirely happy with The Porch. “What’s what wrong with The Porch?!” said Bill Clinton, drinking a snakebite in an Adirondack chair.

Trump ran an Off the Porch campaign, but it was a smokescreen. He’d bought the air rights to The Porch. He’d expanded The Porch and refused to pay his contractors, The Porch was suddenly surrounded by a giant wall covered in fake gold. This, perhaps, is why Big Dogs has reverted to moronic, apolitical form and turned on him for cheap laughs.

Big Dogs are fundamentally criminal but they are competent, at least in criminality. Trump is a failed criminal — an idiot rich kid from Queens who managed to get himself elected president. He can’t even walk down stairs, let alone run with the Big Dogs. With any luck that will be his undoing, but if you voted for Jill Stein or Gary Johnson or Deez Nuts and you’re looking for a hair shirt to wear over the next four years, “The Problem With Political Jokes…They Get ELECTED!” is on sale now at Big Dogs dot com for $12.99 in sizes Medium through XXXXXXL.

Rebecca McCarthy is sort of on Twitter

The Best Book About English Church Music You Will Read This Year

It’s ‘O Sing Unto the Lord,’ by Andrew Gant

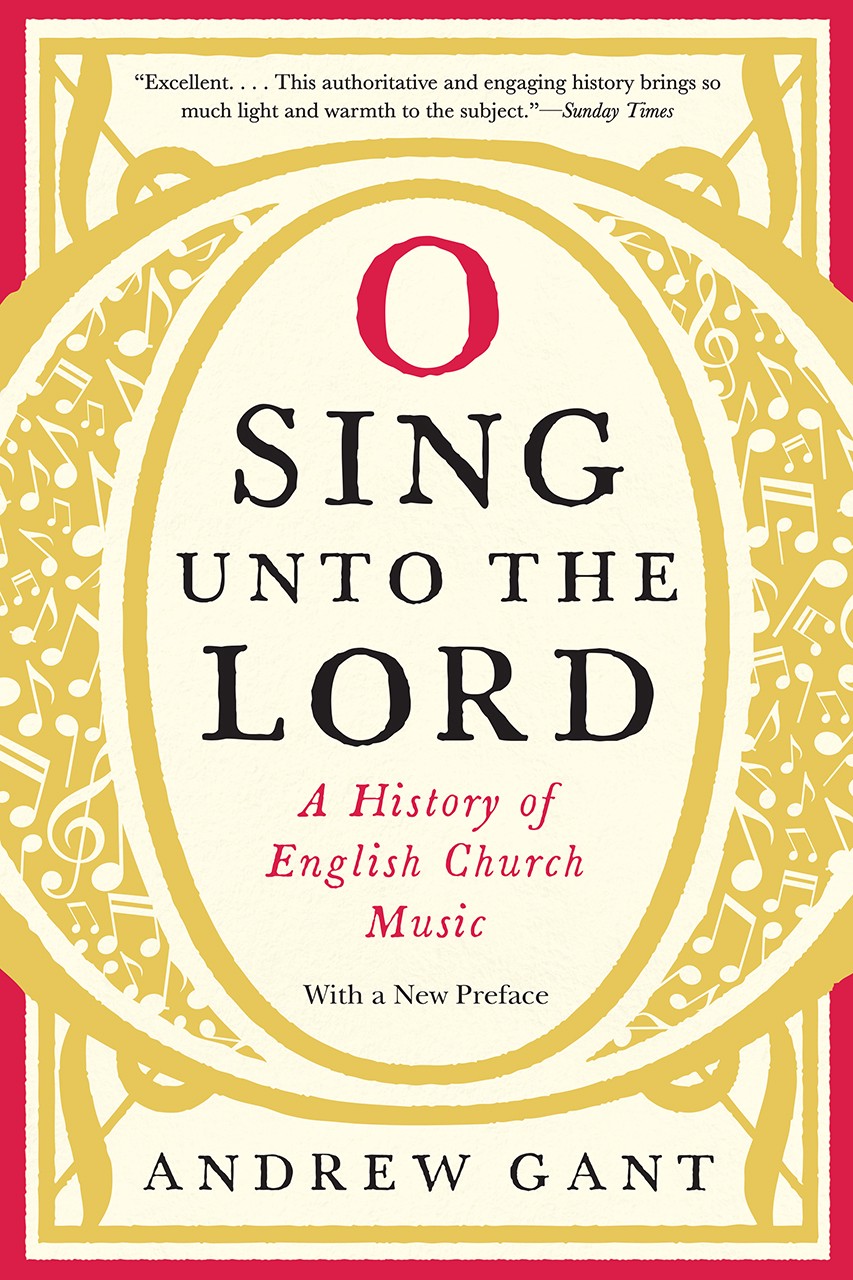

So I was all set to tell you today about Andrew Gant’s O Sing Unto the Lord: A History of English Church Music, which is one of the more delightful books of history I’ve read in a long time, and then everyone’s favorite young composer Nico Muhly pops up in the Times with his own review, which says everything I want to say but in a much more enjoyable fashion.

Nico Muhly on Why Choral Music Is Slow Food for the Soul

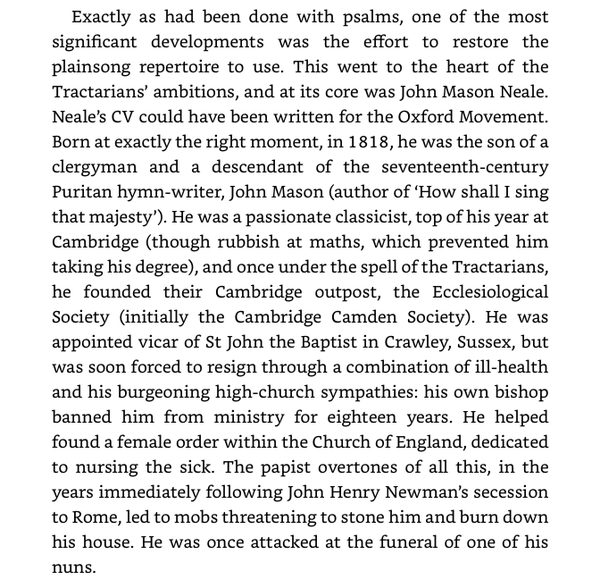

He even made a playlist! You don’t need me at all! I will simply add that this is a terrific book, in which your knowledge of the particular historical eras Gant discusses can only amplify your enjoyment but is by no means necessary for understanding. Here’s a sample passage that should show how light your learning needs be to take a lot away:

Amazing, right? English choral music may not be your thing, which, you know, fine, everyone is different — although I’ve got to say, really, maybe you want to rethink some of your interests if, say, you have a whole lot of opinions of what makes TV prestigious but you can’t tell your Tallis from your Weelkes — but this is a terrific book and if nothing else it should spark your interest in hearing some of the only sounds that are not completely crazy-making in the idiot world which we are apparently condemned to suffer our remaining days. Get it, and maybe start listening to something like this, or this, or the two volumes of this, and see if you’re not somehow set at ease. I promise you when you finish this book you will say to yourself, “I was glad.” (Haha, get it? Ugh, sorry.)

Self-Consciousness

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s work appears in The New Yorker, in Catapult, and on Instagram.

Mountain Range, "What Party?"

I saw the light.

I hope you spent every single second in the sunshine yesterday because who the hell knows if we’re ever going to see it again? (They say we will on Wednesday, but they are full of empty promises.) I guess let’s just settle in for another week of darkness, despair and dragging around a coat you don’t need half the time. This track is pretty good at least. That’s what I’ve got for you this morning. I wish there were more but you know how life is now. Sorry. Enjoy.

New York City, March 30, 2017

★★ A cop loomed over a little cafe table, mountainous in his dark layers of cold-weather gear, chewing. Bright and loose clouds were passing overhead at a pace faster than walking. By the end of lunch the light was diffuse, then it was faded. The damp was back at day’s end, and the lively breeze had turned raw.

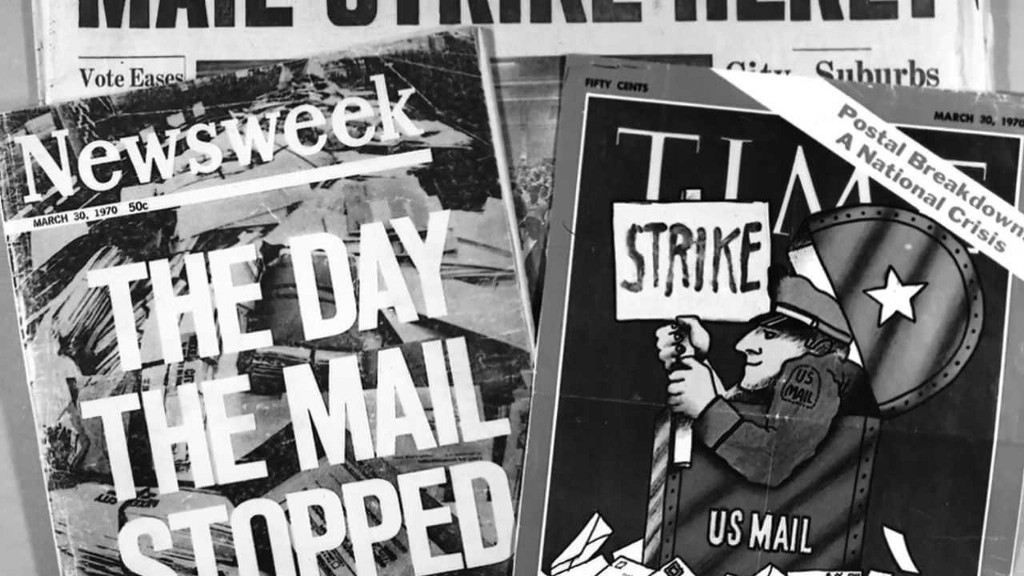

It's Time To Unionize In Silicon Valley

What can programmers learn from the U.S. Postal Service strike of 1970?

In March of 1970, William Burrus watched the National Guard surge into the post office where he worked in Cleveland, Ohio. Burrus, a black man from Wheeling, West Virginia, stood with his coworkers at the entrance of the building as the reserves, clad in fatigues, rifles in hand, arrived in Jeeps and tried to quell a national strike. Postal workers were incensed by a recent vote in Congress that provided them a 4.1 percent raise while giving the representatives a 41 percent spike in pay.

Months earlier, on July 1, 1969, nearly all the letter carriers and postal clerks from the Kingsbridge station in the Bronx had called in sick for the day. When the postmaster suspended the workers, letter carriers from the nearby Throgs Neck station did the same. The members of the National Association of Letter Carriers branch #36 in Manhattan, separate from the Bronx postal workers yet well aware of their actions, had also been tired of low, stagnant wages. On March 18, 1970, they voted 1,555 to 1,055 in favor of a strike. The demonstration started in New York City, but it spread quickly to more than 30 American cities, from New England to San Francisco, as reported by Time Magazine. More than 200,000 postal workers participated, stopping or at least curtailing the delivery of mail far and wide. Many postal workers from the southern states who had never been politically active also took part, Burrus recently told me.

The strike disrupted business on Wall Street, leading New York Stock Exchange officials to consider a market shutdown. An elderly woman living in Manhattan’s Beacon Hotel told Time, “I live on my stock dividend checks and I’m expecting some right now. If this goes on for much longer, I’ll just have to start dipping into my savings.” The poet W.H. Auden worried he would not receive his passport in time for an April trip to Israel. The strike reportedly did not affect the hundreds of thousands of welfare recipients in New York City. Most of these checks were delivered before the stoppage began.

President Richard Nixon, flustered, promptly ordered the National Guard to storm post offices throughout the country and resume the delivery of mail. Burrus, who would later become the first black American to be elected president of a national union, knew that was pointless. You can’t walk into a post office and organize mail like you might organize your basement. It takes training.

“We asked them whether they were going to shoot the mail or sort it,” Burrus said.

The strike lasted more than a week and ended only when the rank and file secured an additional wage increase of six percent. That figure would rise another eight percent following the passage of the Postal Reorganization Act, which Nixon signed into law on August 12, 1970. The legislation established collective bargaining in the industry and allowed employees to reach the top of their pay grade in eight years, instead of the former 21.

Last month, as you might have heard but hopefully did not, Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote a letter to his congregation. In this letter he wrote about “spreading prosperity and freedom, promoting peace and understanding, lifting people out of poverty, and accelerating science,” and his congregation said “amen” and “holy holy” and, prostrated, “Thank you for your leadership and vision, and for putting forward a positive vision that we can all be a part of. This is how we all start to understand each other a little better and make the world we want.” And so it was.

Such idyllic talk counts as standard fare for Zuckerberg and his rival world-engulfing executives. Zuck’s perceived credibility is based on his innovation, which has helped globalize communication — an accomplishment only made possible by a fleet of loyal programmers. Programmers tend to be ethical and trusting, said Valerie Aurora, a former Linux programmer and principal consultant at Frame Shift Consulting. The average programmer is well compensated to work in a nice-to-luxurious office for a company that promises a vision anchored by Gandhisms. The philosophies are strengthened when, for example, Google co-founder Sergey Brin shows up at the San Francisco airport to protest Donald Trump’s immigration ban. Yet despite the gospel of perfection shared by Zuckerberg and other tech giants, they consistently repress the rights of their employees and act in the best interests of corporate expansion, not civic justice.

In the months after the election of Donald Trump, members of the press have contributed several necessary polemics against Facebook’s manipulation of personal data, its propagation of confirmation bias and its overwhelming influence on political thinking, to name a few. Google has relinquished some of its market share, but nonetheless carries on largely unquestioned. It would be fair, by the way, to doubt the potential efficacy of a lawsuit filed recently by the U.S. Department of Labor over requests for compensation data. The clandestine power of these corporations perpetuates their dominance and routinely weakens intervention from government and various forms of activism. The silence around Google and its competitors is by design.

It’s no secret in Silicon Valley that programmers work well beyond the 40-hour week accounted for in their salaries. Aurora said that every one of her friends at Google works nights and weekends. During her time as a developer of Linux kernel, an operating system used in technology sold by Intel and IBM, among others, supervisors constantly assured her and fellow programmers that they love their work and that they love it so much they will do it for free. To ensure persistence and efficiency, supervisors use a complex recipe of emotional abuse and, if you play along, eternal job security.

Many programmers, including those at Google, are told that they are prohibited from talking to the press about their work. They are lectured repeatedly about this rule and ordered to sign non-disclosure forms. Lawyers must review any papers for conferences. Supervisors hold these mandates against their employees, who typically don’t question such restrictions or speak up about harassment so they may keep their jobs. Lower-level employees, who also strive to be a part of something bigger than themselves, desire what anyone else wants in a job: the ability to feed their families, pay the mortgage and have something left over. But as the years pass and the companies grow, this working structure gains momentum at the expense of the rights of workers. Aurora referred to it as “a culture of fear.”

“If you want to have a career in computers,” she said, “it does not pay to talk.”

There should be no muddling of the postal industry, which is dwindling, and the tech industry, which has in many ways taken its place. But discontent is universal. In the 1930s and 40s, when William Burrus grew up in Wheeling, West Virginia, a small town along the Ohio River sandwiched between the more tolerant states of Ohio and Pennsylvania, he attended “a colored school.” In the first four years of his education, he went to five different schools, shuttling between states so he might avoid the brutality of segregation. His sister walked across the river every day to Bridgeport, Ohio, where she went to the same high school attended by basketball legend John Havlicek.

When Burrus graduated high school, there were five nearby colleges that, by law, he couldn’t attend. Brown v. Board of Education was decided two weeks after his graduation, but the uncertainty of its effects led him to the army, followed by a long career as a postal worker. It was not until October 2001 that was he elected president of the American Postal Workers Union. He knows that the AFL-CIO headquarters in Washington was built with the intention that a black person would never work there. He ponders the American invention that states: “all men are created equal.”

“Slavery didn’t mean that,” Burrus said.

In the past few years, Americans have fiercely protested the injustices of powerful institutions. Black Lives Matter catalyzed movements in Ferguson, Missouri and Baltimore, among other cities, that stand for the refusal to accept the killings of young black men. Recent marches countered Trump’s inauguration and celebrated women’s rights to promote gender equality and reproductive health choices. In January, thousands of people stormed airports and streets throughout the country to protest President Trump’s immigration ban. Even Occupy Wall Street, for all its dysfunction, can be viewed as a preamble to the rise of ideas about economic inequality that so many share with senator Bernie Sanders.

Tech workers, despite the massive powers that employ them, have begun to gradually implement traditional forms of dissent. Susan J. Fowler, a former Uber engineer, last month wrote a blog post that outlined a host of internal problems, including gender inequality, sexual harassment and general apathy about these issues from executives and the human resources department. In response, Travis Kalanick, the company’s indignant chief executive, has since launched an internal investigation, to be led by Arianna Huffington, a board member, and former attorney general Eric Holder.

Valerie Aurora could also no longer tolerate emotional abuse, sexual harassment and heavy restrictions, so she left Linux and has since pushed incessantly for labor rights. In 2011, she founded the Ada Initiative, an organization that promoted the rights of women in the tech industry. She champions the activism of Liz Fong-Jones, a Google engineer, transgender woman and daughter of immigrant parents, who advocates for change from the inside. Fong-Jones has worked alongside her colleagues to identify the greatest internal problems at Google, mobilize powerful engineers, devise a request and find those who can grant that request. Keeping with company policy, she has been sure to refrain from talking to the press until internal dialogue is through. After the 2016 election, Buzzfeed News reported that a few dozen Facebook employees launched an unofficial task force to combat the proliferation of inaccurate news.

Aurora and her fellow activists are calling for more innovation in dissent. Otherwise, she said, powerful institutions will too easily dismantle the efforts. “Part of the tension that you get for it is the novelty.” She cited the troubles of Turkish activists, who have tried pioneering mobilization techniques so they may rise above the injustices of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has repressed free speech by forcing journalists out of their jobs and prosecuting online dissidents. There are few examples in the tech field of employees standing for justice over the interests of corporations and government, and their present dissociation weakens their magnitude.

Indeed, a protest can be remarkably effective and still not reach its full potential. Burrus attributes the pattern of activist dissociation to what he called “the imperfection of human beings.” We typically prioritize our rights and the rights of those closest to us over the most pressing civil injustices of a larger scale. “Billions of individuals will rise at their truth,” he said.

The majority of the people in the tech industry would greatly benefit from labor organization not unlike the postal workers before them. However, the frequently corrupt relationship between tech workers and their supervisors, often veiled by the term “meritocracy,” has thus far successfully muted dissent. This silence must come to an end, regardless of corporate motives, and it will occur only when workers throughout the industry stand together for justice over personal, immediate gain. Imagine the havoc if programmers stopped programming, apps stopped updating, and we entered software sclerosis. “Employees who are committed to fairness of employment, even when the government is the employer, can achieve their objectives if they stick together,” Burrus said. “And that’s what happened in 1970. We stuck together.”

Max Rothman is a writer and social worker in New Orleans.