New York City, April 6, 2017

★★★ It seemed as if hitting the stuck umbrella button with a hammer might knock it back into alignment and make it work again, but that was not the case. The majority of the household had not wanted to wake up, and what waited outside was a fine soaking rain, unhurried and unending. Downtown it had intensified into something louder and more quickly drenching; midafternoon brought first white nautical sheets of it sweeping past the windows, then a heavy obscuring deluge coming straight down. Thunder and lightning followed, in the now deep dark of the afternoon. A sheet of standing water with bubbles in it covered the subway mezzanine in Union Square. The windows of an arriving train were so fogged it was impossible to tell how crowded the car was till the doors opened. Minutes too late to have waited out the rain, it ended. The sky was suddenly blue and white, and the puddles in the deeply flooded tree-planting beds mirrored it. An earthworm and a band-aid lay sodden on the sidewalks. In 20 minutes there was light reflecting everywhere, shining in the still-wet leaves of a shrub on the neighboring roofdeck. One last low, rushing mass of clouds, dark with sundown, hurried northward, and through a rift in them came a glimpse of a brilliant spark of airplane, far away in the high remaining daylight.

Jared Kushner Flips Out

IVANKA is reclining on her fainting couch. As always, her phone is within reach. JARED, traveling throughout the Middle East, is calling her repeatedly, but IVANKA has yet to answer. REBEKAH MERCER, daughter of supervillain ROBERT MERCER, one of the billionaires who enabled Donald Trump’s rise, sits at the large dining room table, homeschooling the MERCER CHILDREN. REBEKAH has moved in briefly, to ensure that STEVE BANNON, in a fit of alcoholic, nationalist rage, doesn’t quit his job advising TRUMP. REBEKAH does not ever want to move to Alaska to launch a presidential exploratory committee for SARAH PALIN. IVANKA’s phone rings for the seventh time.

IVANKA [declaratively]: What.

JARED [screaming]: Did he really fucking call me a cuck and a globalist? Did Steve Bannon call me those things? Or is it fake news?

IVANKA: The left is too sanctimonious to falsify facts.

JARED: So he did say it.

IVANKA [whispering]: He calls you a Democrat to your face. What do you think he calls you behind your back?

JARED: Do you know what ‘globalist’ is a euphemism for?

IVANKA [honestly]: Steven doesn’t use euphemisms.

JARED [lying]: I’m not coming back until he quits. From everything. Like Gary [COHN, former President of Goldman Sachs, who also advises DONALD TRUMP] promised before I left on this envoy.

IVANKA [thinking about which left-leaning organization’s back channels she will next explore]: Okay.

JARED: That’s all you have to say about this?

IVANKA [trying to manifest a broken connection]: You’re bold when you’re abroad.

JARED: I fucking ate genetically modified food to foster fellowship with that asshole. We ate Stouffer’s macaroni and cheese. That orange shit is still coating my fucking stomach. And it’s giving me an ulcer. [JARED gags as he recalls the cheese sauce. He takes out a roll of Tums, but they’re the white kind, the only kind the generals carried. JARED winces, bites one, gags again, and spits into the sand. He kicks the sand with his dress shoes. Some of it blows up into JARED’s eyes and he shrieks so loudly the generals look up from their maps and plunder to see if he is alright.]

IVANKA: Stop this right now. I told you to tell yourself it’s a béchamel. [IVANKA raises her voice so REBEKAH can overhear.] We’re all so devastated the generals have ousted Steve from the National Security Council.

JARED: Oh my fucking God. You’re not alone, are you?

IVANKA: Mmm.

JARED [whining]: But I need to know what Steve Bannon is saying about me. Talk in code.

IVANKA: I can’t talk in code because you declined your Mandarin lessons.

JARED: And you never fucking learned Hebrew. The language of my people.

IVANKA [realizing the only way she will get JARED off the phone is by giving in to him]: Ekahbay Ercermay isay erehay.

JARED [kicking the sand again]: Rebekah Mercer is in our house? The God damned First Lady of the alt-right is where our children sleep?

IVANKA [still speaking pig Latin]: Annonbay eatenedthray otay itquay.

JARED: Gary promised me he was getting fired. Why does he still have any power whatsoever? After calling me a cuck. Have his walk-in privileges at least been revoked?

IVANKA: I told you I couldn’t talk about this right now. [REBEKAH MERCER walks over to IVANKA and asks her if everything is alright. She shows her an executive order her child has written for homework. The order would privatize Amtrak and permit nuclear waste to be buried underneath the 30th Street Station in Philadelphia. IVANKA, complicit but polite, nudges REBEKAH MERCER back to the table.]

JARED [slapping his own face]: My fucking head is splitting. I should’ve brought my French press. The generals drink ration coffee and it tastes like that gross cabin we went to on the campaign.

IVANKA: I’ve already explained it wasn’t a cabin. It was the General Motors plant. And we won Michigan so you’re not to disparage their coffee choices.

JARED [having an epiphany]: What if Bannon wants me to be angry with him? What if this is a trap?

IVANKA [sternly]: Go back to your tent, find your Netflix and watch Bob Ross paint. Right now.

JARED: He wants me to flip out. He’s probably recording this conversation right now. Fuck. What the fuck, Ivanka. Breathe. [JARED breathes rapidly.] My fucking Headspace app. It started updating, and now it’s just, like, hanging there. I can’t open it and I can’t delete and reinstall it either. [JARED cries.] He’s playing three-dimensional chess with us and mom only ever let me beat her at checkers. I don’t know how to play chess.

IVANKA: Three-dimensional chess was a metaphor the left devised because they only know how to self-defeat. [IVANKA mutes JARED.] Bekah, dinner is served at 7. It’s gluten-free and genetically unmodified. I hope you don’t mind. Jared has some allergies and so we’re all on his special diet. It makes it easier for the kitchen staff if they only have to prepare one meal.

JARED [unmuted, still crying]: I don’t know how to play chess.

[STEVE BANNON barges into the room. He is wearing a Confederate soldier’s uniform he has stolen from the Smithsonian. The buttons won’t fasten and it’s covered in vomit and diarrhea, so it’s more like a small dirty cape than a military uniform. STEVE BANNON explains to REBEKAH MERCER that he is not reenacting the War Between the States. It’s red states versus blue states now, he bellows. She rises and asks how she can help.]

IVANKA [talking over STEVE BANNON’s booming slurs, so as not to further trigger JARED]: Why don’t you tell me about a new business you’ve come up with? For daddy’s SWAT team.

JARED [scream crying]: Tell me what else he said about me.

IVANKA [slightly flustered]: Jared. Kushner. Pitch me.

JARED [stifling his tears]: It’s like Chipotle but for Middle Eastern food. You can say if you want kebab or falafel or hummus. And then which toppings.

IVANKA [lying]: Brilliant. [IVANKA shouts so STEVE BANNON can overhear.] And we can commandeer heartland agribusinesses. [IVANKA whispers to JARED.] In order to grow genetically unmodified chickpeas. Instead of corn and animal feed.

JARED [relaxing]: You always know how to calm me down. [JARED smiles at a CIVILIAN BOY who is asking his mother why the tall American boy is so sad.]

IVANKA [while hanging up]: What else are you learning? [IVANKA walks over to the white nationalists in her home and offers them a drink.]

JARED [to himself]: It’s like Aladdin where I am but there’s no genie, and the sand is — Well, I guess I never have touched sand before this vacation. It’s itchy powdery? [JARED turns to the CIVILIAN BOY.] Do you know of a good coffee shop around here?

Why Not Live With Friends?

Affordable rent in New York City’s last Quaker boarding house.

In 1897, the Religious Society of Friends — more commonly known as the Quakers — purchased a stately brownstone on Manhattan’s East 15th street, and formed the Penington Friends House. Under the guidance of a local Friend named John L. Griffin, the house was established to provide housing for elderly Quakers, and to offer supervision for Quaker women traveling through New York City. Griffin’s portrait still hangs in the parlor at the Penington Friends House. And his motto, “To share a meal, at reasonable cost, with Friends and friendly people” still guides the residence. The house now shelters twenty-four long-term residents, of varying ages, faiths and creeds, and has two spare guest bedrooms, which are rented out on a short-term basis.

Around 9 a.m. on a Sunday in February, Lem Schaefer was making Sunday brunch for a few of the house’s residents. He brought out large, billowy batches of scrambled eggs and loaves of fresh wheat bread. Lem is in his early seventies and is a retired seminary administrator; five years ago, he moved to New York from Denver, Colorado, to help take care of his grandchildren. Residents describe him alternately as the grandfather or the mayor of the Penington Friends House.

Penington is a boarding house, a bygone housing option for single city dwellers on a budget. More adult than a dorm, more permanent than a hotel, and more affordable than a single apartment, boarding houses have largely been eclipsed by the tradition of roommates. Penington remains one of the last boarding houses in New York City, and the only Quaker boarding house in the five boroughs. Quakerism first hit America in the seventeenth century, when its believers fled religious prosecution in England.

A commitment to fairness, teetotaling, pacifism, and austerity continue to be the bedrock of Quaker values. The main tenant of Quakerism is the belief that every human has an inner light, a flicker of God living inside him. But their numbers are declining, no doubt in part because of the Quaker resistance to evangelizing.

The rooms at Penington, for both guests and residents, are affordable, modest, and private. “The Phebe Room” is three creaky flights above the ground level and rents for $120 a night. The room is open to singles or couples and includes a double bed, a nightstand, a wood chair, and a half bathroom. Lem’s room is about 8 feet by 13 feet wide, which is typical. Each resident’s room includes a twin-sized bed, a desk, and a closet; large pieces of furniture are discouraged. Residents are allowed to live in the house for up to five years, although exceptions have been made in the past. The monthly rent ranges from $1068 to $1700, and includes the room, utilities, cable, WiFi, a New York Times subscription, help-yourself breakfasts seven days a week, and a home-cooked dinner Sunday through Thursday nights at 6 p.m. Each guest room has a toilet ensuite, but everyone shares the communal showers, which are clean and well maintained. There are ample common spaces, including a large parlor, a dining room, a nook for watching television, a large backyard, and a roof deck.

Next door to the Penington Friends House is the Quarterly Meeting, a Quaker church where all are welcome at the two weekly services. Quaker services eschew scheduled programming. There is no preacher or sermon or singing — Friends may stand and speak when they feel compelled by their inner light. Over breakfast, AJ Parillo, a physical trainer and voice-actor who has lived at Penington for about twenty years, recalled Paul Myers, a resident who was in his eighties when AJ moved to the house in 1996. Paul would regularly attend the Quarterly Meeting’s Sunday services, and preferred the 9:30 a.m. devotional, as the 11 a.m. service has a raucous reputation. One Sunday morning, AJ asked Paul how things were at the Quarterly Meeting. “Noisy,” Paul replied. AJ asked him how many people had spoken during the service. And with great annoyance, Paul retorted, “One.”

Paul Myers would have enjoyed the service that I attended, as nobody felt compelled to speak in the service’s duration. In Quaker churches, the pews face the center of the building, and the interior resembles a theater in the round. There was no announcement that the service had commenced, and it was difficult to tell when, if ever, the service actually began. At the first, the Friends stared straight ahead, silent in devotion. But as the service wore on, everyone began to slouch, like passengers settling in for a long flight. A few minutes after noon, a young man, sitting just off center, rose and said, “Good morning!” as if he were seeing us for the first time. Everyone shook hands with their neighbor, thus concluding the service.

Although the Quarterly Meeting is attached to the Friends Seminary elementary school, the two institutions parted ways several years ago. Some Friends of the church thought that the school was neglecting the Quaker community, and instead catering to Manhattan’s elite. The yearly tuition now exceeds $40,000. There were questions of austerity, homeliness, and modesty — principles that are central to the faith. A 2011 New York Times article summarized the division by saying, “In the meetinghouse, worshipers sit on benches with horsehair cushions. In the office of the school headmaster is a velvety Jonathan Adler sofa.”

Penington represents a kind of middle ground between the Quarterly meeting and the Friends Seminary, and the house has an adherence to Quaker values without necessarily subscribing to the Quaker religion.

The house manager, Rie Ma, presides over the resident application process — which includes personal essays about the importance of community, and reference checks. Most applicants are young adults getting their footing in the world, and the two live-in managers make a conscious attempt to cultivate a diverse group of residents. Being a confirmed Quaker is not a requisite for living in the house, but having a respect for Quaker values is. Kathy Jaeger, the facilities manager, told me, “The younger people can give some energy to the older people, and the older people can give some wisdom and experience to the younger people. You’re living as extended families used to, but don’t anymore.” While only three of the house’s current residents are practicing Quakers, Penington would like to host more of them. “Our mission is to serve Quakers,” Jaeger said. “It’s the only group that’s getting a preferential showing. All things being equal among a group of applicants, we would take the Quaker, regardless of race, or age, or what have you.”

Life at the house is not without its responsibilities and residents are expected to be actively engaged in fostering community. “You do give up some personal freedoms by living here. You can’t give your keys to your friends while you’re away, you can’t have have people over willy-nilly. When it’s your turn to clean up after dinner, you can’t skip the meal. You can’t clean the bathrooms when you feel like it; you’re on a schedule. We expect that you would share dinner with your housemates, and we expect that you would be in attendance at house meetings” Jaeger said.

These monthly meetings are a space for addressing any issues that arise within the house. But in accordance with Quaker tradition, residents are not allowed to simply vote on a matter. An issue is discussed until everyone comes to an amiable solution — what Quakers call, “finding the sense of a meeting.” “Even if everyone doesn’t 100% agree with a solution,” Rie said, “the goal is that everyone has an understanding of everyone else’s point of view.” Ideally, this encourages empathy among the residents. But at its worst, this system brings decisions to a standstill. “Everybody gets to have their say. And until we can all agree on it, it’s not going to move forward.” said Kathy Jaeger.

Kathy Mitchell, Penington’s oldest resident, is fed up with the consensus charter. “I can’t stand that part of the house,” said told me in a hushed voice. “Sometimes I just wish we could put it to a vote!” Speaking in the parlor, Kathy Jaeger told me, “It took us two years to get that sofa reupholstered!” One of the most contentious issues is the house’s 6pm dinner time. And over the years, attendance has dwindled, as the younger residents, many of whom are students, can’t always make it home in time. The dining room is on the house’s garden level, and has a long, clear-lacquered wood table, where residents sit and eat. Although attendance is not required, residents are expected to attend dinner when they can, as it is where most of the house’s socializing takes place.

“One of my major complaints is that the managers don’t sit down to have dinner with us. I tell them, ‘Community starts with dinner,” Lem said. “That table downstairs used to be full all the time, but now, sometimes we just have four people.” But that Sunday night the dinner table at the Penington Friends House was in rare form, and full. The food was laid out in an L-shaped buffet on the island dividing the kitchen and dining room, and a mass of residents culminated just after 6pm.

Penington was in the process of hiring a new chef, who would cook a few dinners per week. On the night I stayed for dinner, the house was auditioning a potential candidate. She served baked chicken with tomato and saffron — the meat fell off the bone, and the tomato sauce was sweet and oily. The whole concoction was baked and served in a cast-iron pot. We also had tabouleh salad, okra topped with tomato and yogurt, and a vegan quinoa soup. Dessert was rice and pistachio pudding with bits of cinnamon.

I had heard grumblings that the current chef never joined the residents for dinner — she always seemed to be in a rush out the door. But that evening’s candidate won the house over with her willingness to linger and chat. (Her food was a hit too.) I later discovered why the 6 p.m. dinner time was such a contentious issue, because by 11 p.m., I was hungry again. I made my way down to the kitchen, hoping to find some leftovers or a piece of fruit, and I was not the only one. About half a dozen of the residents had a similar idea and were scrounging together leftovers and peanut butter sandwiches.

In the past few years, there has been a rise in companies offering “co-living” situations—Greek life for grownups and an alternative to finding roommates on Craigslist. They offer shared housing with high-speed wifi, flexible move-in dates, and a West Elm catalog’s worth of particleboard mid-century furniture. But more than just a fully-stocked kitchen, these companies sell the opportunity to meet like-minded individuals. Common, a co-living company based in New York, advertises, “Co-living, co-eating, co-playing, co-creating. This is what it means to live life in common.” The implication is that you aren’t just paying for a room — you’re also paying for a community.

When I arrived at Penington, I expected to find a variation of these co-living situations: WeLive of the 19th century. Common’s cheapest rooms rent for around $2,000 a month, and the whole co-living fad seems to be an excuse to network with people your own age. In its own Quaker way, Penington is appealing to that same desire for community.

The real difference between these co-living companies and the Penington Friends House is the type of community that is being fostered. Penington’s managers have made a conscientious effort to cultivate an assorted mix of young, old, newcomers, longstanding residents, atheists and believers. AJ Parillo described the ideal resident makeup as a healthy forest: old, sturdy trees work symbiotically with newer, younger shrubs.

This type of environment, one where you can choose to live with people whose walk in life greatly differs from your own, seems to be Penington’s real attraction besides the affordable rent. Politically, the residents skew to the left, but no more so than the average New Yorker. Penington’s most remarkable feature isn’t its longevity. Rather, it’s that students, grandparents, voice actors, non-profit administrators, atheists and devout Catholics can all be cordial at the same dinner table.

Jack Lowery is a retired dog walker.

Dial D for Dolphin

A telephonic mystery.

My landline rang. The Caller ID listed no name, but the phone number was similar to mine. Same area code. Same prefix (first three digits). “Hello?” I answered.

Silence. Then, click.

I get a hang-up almost every single day. A low estimate would be two hundred per year. I never call back. But this time, I did. I’m not sure why. Perhaps I was concerned that it was an important call — someone calling from my son’s school, maybe. Or maybe I was a little annoyed that someone called me only to hang up on me when I answered. Maybe I was bored. Maybe I was curious. Maybe a little of all those things.

“Hello Flipper,” a drowsy, robotic female voice greeted me. Then I heard the shrill trills of an actual dolphin. “Press 1 to connect with your fish,” the robot commanded, now sounding more sprightly. “Press 2 to let it go.”

Huh? Who or what did I just call?

“I’m sorry, I didn’t get your response,” the robot told me, and she sounded somewhat forlorn now. “Please enter 1 to connect with the fish. Enter 2 to say goodbye to Flipper.”

I followed my instincts. I pressed 2 to let my fish go.

It hung up on me.

What?! What the hell was that?

I called back. This time I pressed 1.

“We are connecting you to your fish,” the robot assured me.

I waited.

“This is exciting,” Tyler Wilcox said after he pressed 1 on my phone. He waited. “Are you there?” No one answered him. “Is this the sound of a fish?” He looked at me. “I don’t know what to say to the fish.” Then he said, “I don’t think there are fish on the phone waiting. Does it just keep going?”

I didn’t answer.

“All right,” he said, hanging up the phone, “disconnect from my fish. I’ve gotten what I need.”

I asked him what he thought about it.

“This is kind of terrifying. I feel like these kinds of things never end well.”

“For who?” I asked him.

“I don’t know. It just ends up with you standing in a room somewhere, looking in a mirror, and you realize that you’re a dolphin maybe? It makes me think of Lost Highway…That’s what you’re going to get sooner or later: Flipper is in your house. Like you’re going to connect to the fish at some point, and it’s gonna be like, ‘Hello, David. We’ve been waiting for you.’ Something is going to happen,” he concluded, and we laughed.

But there was something slightly creepy about it.

The next day, I awoke thinking about Flipper. Specifically the drugged-out, sinister quality of the robot voice who said “Hello Flipper.” It wasn’t a greeting like, “Hello, Flipper!” And it wasn’t a name like “Hello Kitty.” It was more like “Hulloflipper.” It almost sounded like she was taunting me with a made-up word. Like she was HAL 9000’s more primitive sister — just as evil, but with no interest in hiding it.

I scrolled through my Caller ID, found the number, and dialed it back again.

Hulloflipper…

I had expected the number to be out of service. But there it was. I pressed 1 to connect with my fish. And I waited. And waited. No one answered. It didn’t disconnect me, but it just let me hang there. No hold music. No occasional assurance that my call would be answered soon. Just nothing. Eerie silence. Or were there ghostly voices somewhere in there?

I asked if anyone was there. (Could anyone hear me? Was I being recorded?) No one answered. Eventually I hung up.

There had to be an explanation. I came up with a few theories.

Perhaps there was a reboot of the “Flipper” TV series in the works, and this was part of some weird marketing campaign that had gone live prematurely. Or maybe it was a college psychology experiment. There was something in the language, “connect with your fish” or “let it go” that seemed somehow significant.

I took to Twitter and searched there. Nothing. So, I tweeted about it myself, and found nothing more than further validation that I was, in fact, not completely crazy to be researching this: Starlee Kine (host of the endlessly entertaining podcast “Mystery Show”) liked my tweet.

I went to Google. I searched various keywords and found absolutely nothing at first. Then, finally, I hit upon just the right combination of search terms, and there it was: Flipper. All of it. All of it and more.

I gave my friends, Jeff and Jessey Eagan, the phone number to dial. “…It’s roping you into this whole mind meld of whatever they’re trying to do to you. They’re winning, I think, as well.”

While there were countless Google results for Flipper, there was only one result for my Flipper. It was found on GitHub, a massive, sprawling website dedicated to posting and collaborating on code. This page was the motherlode. Actually it was more than that. It was Flipper. Flipper’s code. And it dated back to 2014.

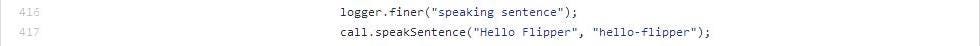

Here’s an example:

It takes 417 lines of code to finally get there, but there it is: “Hello Flipper”. Then there’s this, from line 469:

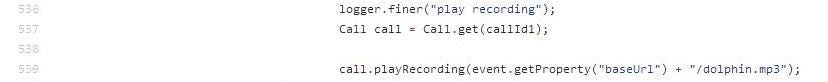

And that sound of the actual dolphin? Let’s visit lines 536 to 539:

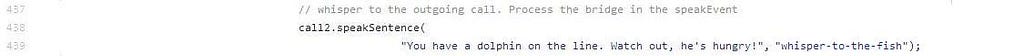

Like I said, there was more — additional dialogue that I hadn’t heard. Here’s lines 437 to 439:

In all my times calling the number and pressing buttons and holding the line to be connected to my fish, I had never heard it tell me that I “have a dolphin on the line,” and to “Watch out, he’s hungry!” And what did “whisper-to-the-fish” mean?

I couldn’t tell what any of it meant because even though I was looking right at the very DNA of Flipper, I couldn’t read it. Nearly 700 lines of Java code. I can’t read Java.

Github listed three users who posted (and presumably wrote) the code: swmitchell, smitchell2240 (an alias of the first?), and lfavaro-daitan. These were the people who knew what Flipper was, why it was calling me, and what it was doing when I called it.

Neither of the S. Mitchell accounts listed any contact info or identifying information. Lfavaro-daitan’s profile listed his name, Luciano Favaro, his email address, and where he worked (both the company, and his location in Brazil). I emailed him and told him I was writing a tech-related story about a phone-based application that I found the code for on GitHub. Six minutes later, he wrote me back: “Hi David, could you give me more details?”

Delighted, confident, I wrote him back and told him that I would be glad to tell him everything on the phone. He did not write back. The next day I sent a quick note assuring him that this was a humorous story, and asked again if he could spare me some of his time. He did not write back. A few days later, I followed up again. He did not write back.

The next week, I emailed him again, and I gave him the option of using a pseudonym. He did not write me back. I called his work. He did not have an extension, the receptionist told me. Luciano was elusive. But it seemed to me, he was merely a collaborator on the code. Smitchell2240 was the actual uploader.

I registered as a GitHub user hoping to unlock a messaging feature. But there wasn’t one. So I navigated to another project that smitchell2240 had worked on and left a comment asking for him to get in touch with me, and provided my email address. I heard nothing.

Smitchell2240 was only followed by one other user: dtolb, who had a much more robust presence on GitHub. His name was listed as Daniel Tolbert. I very easily located Daniel’s email addresses and sent him a note asking if he could help me get in touch with smitchell2240. I heard nothing.

I took to Google and searched if there was a way to contact a GitHub user who didn’t post an email address. I read through various threads and learned that there was a time when the site actually did offer a private messaging feature, but they had since removed it. And then I found a thread on StackExchange.com that explained how one could find a user’s email address by following a list of steps. “Clone on your local machine the repository,” it said. “Search for an event stating ‘user_test pushed to [branch] at [repository]’…” None of it made any sense.

I texted my friend and colleague Ben Cramer in New York, and I told him to call the number. He wrote back, “I love it. It’s the best possible outcome of a call we would all assume to be some malicious effort.” I gave him a ring and asked him to walk me through his experience calling the number.

“I’m just playing arm-chair psychologist on myself, which is kind of what I do, I guess, I don’t know. I’m not a fisherman…it’s not even a fish, is it?”

A few days later, I attended a dinner party with our friends The Welles. As our kids scrambled off to play, I met Sarah Welle’s brother, John Erck who was in town from California. We enjoyed gin and tonics as the kids ate mac and cheese, and I told myself to not bring up Flipper, because it seemed like a weird dinner party topic. But then when I asked John what he did for a living, he told me he was a developer. Jamie Welle is also a developer. I was sitting right across from two developers, and we’d just put a movie on for the kids.

So I told them about Flipper. Actually, I didn’t tell them. I pulled out my phone, dialed the number and put it on speaker so they could hear it. “Hulloflipper” the robot intoned. “It’s kind of creepy!” Sarah Welle said. I told them I had found the code on GitHub, and before I could say anything else, both John and Jamie got up from the table to get their laptops. The dinner table quickly became mission control.

What followed was a solid 30 minutes of them reading through the code and all of us hypothesizing. Jamie was fairly sure it was a sample app. He said “it looks to be an example for an app called the Bandwidth app. So this is code they provide if you’re learning how to use the Bandwidth app. To give you an idea of how to use it.”

John wasn’t so sure. He wondered if “maybe it’s an experiment.” Jamie was mainly curious about the purpose of the app. Reading through the code, he found mentions of bridging calls and creating outbound calls. This made Sarah wonder if by calling in, we were “creating a call to a new victim.” It didn’t seem like a coincidence that the Hello Flipper number was local to my own phone number. We tested a theory: if we input a phone number after we connected to our fish, could we bridge (or merge) the calls together? Jamie called Hello Flipper, pressed 1 to connect to the fish, and then typed in John’s phone number. We waited in suspense, but John’s phone failed to ring.

“Maybe they’re testing the idea of calling from local numbers to local people to get an uptick in their answer rates…So maybe the dolphin is an insignificant part of the app,” John hypothesized. Jamie looked up the company called Bandwidth and found that they offered voice and messaging APIs and services. They even leased phone numbers.

If the app was really a sample application, then why was it deployed and active? Especially since it was written in 2014, and this was nearly three years later. And also: Why Flipper? What was with the fish stuff?

The only person who could answer these questions was smitchell2240. I got Jamie and John to decipher the instructions for conjuring a Github user’s email address and got not one but two email addresses. One personal, one work. And he worked at Bandwidth. And smitchell2240’s one GitHub follower was also a Bandwidth employee.

I tried Steve’s personal account first. And I gave it a few days. But he didn’t write me back. So then I emailed at his work email address. Again, he didn’t write me back. I tried emailing Daniel Tolbert again. He didn’t write me back. I tried emailing another follower of a Flipper collaborator who also worked at Bandwidth. He didn’t write me back, either. I emailed Steve again at both email addresses, assuring him that I just wanted to solve a mystery. No response.

I tried calling the office and asking for him. He doesn’t have an extension, I was told. Then Jessey Eagan found something big: Steve had posted a GitHub comment, and it included his auto-signature, which included his phone numbers. So I called him. And called and called and called. But he never answered.

While I was spinning my wheels trying to reach Steve Mitchell, it occurred to me that speaking with literally anyone at Bandwidth would be progress. So I called their main phone number, and asked for the company’s PR person. They didn’t have one, they said. I asked who handles their media inquiries. Noreen Allen, I was told — their Chief Marketing Officer.

She was energetic in how she described her firm. “We work with companies that want to do cool, interesting things with voice and messaging services. So if you want to embed voice…[or] calling capabilities or messaging or texting capabilities into your app, into software, if you want to do something innovative with it in a new product, you come to Bandwidth.”

I asked her about scammy and strange phone calls that used software-based technology, and she was emphatic that Bandwidth had no tolerance for such a thing. She also told me that Bandwidth leases phone numbers to its customers and provides them with the ability to hide their own actual phone numbers. She explained that many services, such as Lyft, do the same thing, and it’s not just for privacy concerns, but also to protect revenue. After all, if you know the direct number of a Lyft driver you liked, you could just call that person directly and bypass Lyft all together.

I asked her if Bandwidth provided apps written with, for lack of a better term, “sample copy.” Lorem ipsum for telephone APIs, if you will. “Yeah, we do,” she answered. “We provide what are called SDKs or Software Development Kits and sample code for some very basic functions so that a developer, if they want to perform some of these basic functions using our platform, can take advantage of some of that sample code.” she explained.

Jamie Welle had pointed out to me that Hello Flipper was an SDK. Sensing that I might be closer to getting some answers about Flipper, I asked her if it was possible that sample code could be deployed. “I’d have to bring one of our developers on to ask about that. I don’t get into all the details on the development side,” she said.

She offered to arrange an interview with a developer. I asked her if she could connect me with Steve Mitchell in particular, as I had identified him as the possible creator of an app that I was interested in. She happily agreed. Feeling more confident than ever, I decided to do one last thing before we said goodbye: I decided to do a three-way call with her and with Flipper.

“That was very odd,” she said after it asked her if she wanted to connect with or let go of her fish. I asked her which option we should choose. “Let’s say hello to our fish,” she decided.

After I disconnected with Flipper, I asked her what she thought. “That sounds pretty bizarre. How funny. That is interesting. Very interesting. There’s some interesting stuff out there for sure.”

I awaited an email introduction to Steve from Noreen. No such email came. I had one last option. I texted him. “Hi, Steve!”

“Who are you?” he texted me back two minutes later. It had finally happened. I was actually communicating with Steve Mitchell.

“Flipper! Trying to decide if I should connect with my fish or let it go,” I texted back, thinking he’d appreciate the reference. No response. So I tried again, this time explaining that I’m a writer working on a fun story, trying to solve the mystery of Flipper. And I offered up-front for him to use a pseudonym.

“What’s your byline? Where can I read your material?” he wrote back.

I sent him an article I’d written about having Crohn’s Disease and a love for craft beer, and an essay I’d written about my favorite Stephen King book and how it was a sort of blue-collar White Noise.

“What do you want from me?” Steve asked.

I told him I wanted to interview him.

“About what?”

Frankly, at this point, it felt as if I was repeating myself, but I explained it again. I wanted him to help me solve the mystery of Flipper.

“What’s the mystery?” he texted back. Then “It’s a sample app.” And then “That’s all,” and then, “No mystery.”

I didn’t want to argue with him. I assured him this was a fun story and pleaded for just 10 minutes on the phone.

“Sorry.”

“You won’t?” I asked. “Do you know Flipper is live?” I asked.

“If you have questions about it, please contact sales and marketing,” he wrote back.

OK, I told him, but would it be alright if I sent him any follow-up questions via text?

“Best to talk with sales,” he said.

That was the last I heard from Steve Mitchell.

I called Bandwidth back and tried to interview a random support person about Flipper. He wouldn’t comment, and instead got in touch with Noreen Allen. Perhaps sensing that I might eventually reach someone on their sales or support line who would speak to me, she called me back promptly. She explained that she felt like the story was going in a direction that she didn’t want Bandwidth associated with.

I leveled with her that I knew Flipper was a Bandwidth product. I told her that I wanted to interview a developer there because everyone who heard the Flipper app was intrigued by it. To my surprise, she agreed, and said she’d speak to some developers and see about arranging an interview.

Instead, a week went by and I got no word.

Noreen disappeared, Steve refused to respond, and the support people would not speak to me on or off the record. It made about as much sense to me as Hello Flipper itself. Why would they stonewall me over a sample app about a dolphin? Why all the secrecy?

I sent another friendly email to Noreen, and she sent this prepared comment:

We routinely create sample apps to [sic] for developers that illustrate the development possibilities of our voice and messaging APIs. Oftentimes, we’ll have fun with these sample apps and do something around a holiday, something tongue in cheek or pop culture-related. As an example, we created a sample app around Valentine’s day one year, where you could text or call a number we provided to receive a Valentine’s day greeting. The apps are not intended to be serious — they’re designed to spark creativity and illustrate a use case in an engaging manner.

This statement did nothing to satisfy my curiosity. Getting a “Valentine’s day greeting” on Valentine’s Day was not mysterious, and would not have sent me on a weeks-long hunt for answers about a 50-year old dolphin. It would not have inspired my friends to call the recipients of those greetings “victims.” Hello Flipper was not the same as a Valentine’s Day greeting on Valentine’s Day.

Plus, the statement also failed to address a pretty fundamental question: why had the “sample” come to life three years after the code was published? I thanked her and asked one last followup: how is a sample app live, and how is it making outbound calls?

She responded: “My colleagues determined that a third party made outbound phone calls to you by ‘spoofing’ that phone number. We take prompt action to address any spoofing incident that comes to our attention.” In other words, someone happened to spoof a phone number that traced back to a machine running the Hello Flipper app? What are the odds, I wondered. And anyway, a spoofed phone number told me nothing about Flipper.

A few days later, I had a beer with another friend of mine, Matt McKinney. I thought it would be a good idea to get one more recording of someone reacting to Hello Flipper. Like with my other friends, I gave him no preparation or introduction.

“Fuckin’ Verizon,” Matt muttered, thinking the call wasn’t connecting.

I got a sort of nervous, bad feeling. “Whoa, what the hell?” I said. “Nothing?”

I don’t know for sure if Bandwidth pulled it down, though the timing would suggest it. Or maybe it was a coincidence. Maybe the person who had deployed Flipper pulled it down on their own. As I write this, the Flipper code is still up on the Bandwidth repository on GitHub. But it’s no longer there when you dial the number.

Flipper had been driving me a little crazy. It was a maddening mix of dumb and mysterious and weird, and the fact that the company who created it flatly refused to talk to me about it (aside from two vague and nearly meaningless statements) only made it worse. Or did it make it better?

The likely truth is that Flipper really was just a mundane sample app, and it was accidentally deployed. The mysterious bridging-calls code was probably there to show how it could handle incoming calls, then create and route (and bridge) those incoming calls to a customer-support or sales queue. Sure, that still didn’t answer why it was making an outbound call, and I still had no idea why someone wrote code about an aquatic mammal from 1960s television show. But that’s very likely what the app was meant to demonstrate. But coming to that realization was the least rewarding part of the entire process.

Maybe, or almost certainly, Flipper was written about Flipper and fish because it was just a dumb joke between developers. But once it escaped from those confines, it took on a life of its own. And quirky/funny became something that one person said was “terrifying,” that another person compared to a David Lynch movie; when another person heard it, she called it “creepy”; when another person heard it, he thought it might be “an experiment”; when two other people heard it, they joked about how if something happened to me, they’d know the first thing they’d think would be “Hello Flipper”; and when someone else heard it, he said it was something everyone would “assume to be some malicious effort.”

After a month of obsessing about Hello Flipper: what did I really want the most? The mundane truth, or the dark mystery? Why had I called a hang-up back in the first place? And then why did I care about some primitive robot voice on the other end? The night I discovered Flipper was dead, I told my wife. She asked me, “Are you surprised?” I told her I wasn’t. But I was sad — even if the code itself was still there on GitHub, it just wasn’t the same. I wanted that drowsy, persistent robot to be out there in the wild, asking anyone who called it if they wanted connect to their fish or let it go. I wanted Flipper to trill at callers, to amuse them, to confuse them. There’s some interesting stuff out there, for sure.

David Obuchowski is a freelance writer and a musician. His features on craft beer, literature, music and culture have appeared in Deadspin, Gawker, and The Daily Beast. He plays guitar for Publicist UK (Relapse Records), Goes Cube (Old Flame/Greenway Records), and other projects.

Brooklyn Academy of Music

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

OK, you were not quite a stranger, in that you were a known person. To me, more-than-known — an idol, almost, which seems a preposterous word to use about a person who is neither Rihanna nor Beyonce nor the Virgin Mary, but a late-middle-aged white guy called Steve. A guy called Steve in a baseball cap. I speculated on this trademark headgear as if it were a relic-in-the-making. “How many hats do you think he has?” I whispered to my husband, carried away by my own inanity. Easier to be inane than awestruck. “Or is it just the same one, always, and it smells really bad but no one says anything?”

My God, I would have been so mortified if you’d overheard this. As with Beyoncé, your name is a sort of impossibility — something separate, in my mind, from a human being who yawns or makes coffee or files taxes or is bewildered to overhear his wholly unostentatious hat discussed by strangers. Instead, your name registers as the designation of a kind of god. I know this: that the work is the godly thing, not you, but still, it has your name on it.

You wrote a piece of music I listen to as regularly as I shower. Like showering, hearing it is a kind of hygiene. I sit up, plug in headphones at my laptop, and the sound is Pavlovian; I feel like a pianist, fingers raised with readiness above the keys. I am instantly alert, vivified, braced into sentence-making, brisk-thoughted mode. Most miraculously, its magic doesn’t seem to wear out. Maybe because it’s not really ‘music’—that’s too diaphanous a term for a thing that’s more an exercise, a communal, moving construction — architectural and yet effulgent. I privately declared a relationship doomed when I saw this piece of music at the Park Avenue Armory and my companion idly checked his phone as soon as the applause began. He might as well have taken a dump in the Sistine Chapel. A pair of techno DJ friends wed to this piece of music, notes sounding radiant and staccato from a Marshall amp on the DUMBO waterfront as we witnessed from hot stone steps and one of us cried.

No way I could say any of this to you. Instead, I did something quite creepy. This is what I hope you didn’t notice: me, shifting a fraction to my right as you passed me in a crowded room just so that, yes, I could say I brushed shoulders with you.

Forgive me. There’s such satisfaction to enacting an idiom. Years back, when my husband-then-boyfriend were looking to move in together, we went hand in hand like poor fools to a broker, a sardonic Polish lady in her sixties. We announced our budget to her whereupon she actually laughed in our face. Rather than dismay or indignation I felt delight at a turn of phrase made literal. It was like watching someone slip on a banana skin, or run off a cliff and pedal, manic and suspended, before the plummet. (Once she’d laughed, lo if she didn’t find us the cheapest damn rent-controlled railroad in north Brooklyn.) In French, to stand someone up is to ‘poser un lapin’, or, to place a rabbit. I have always loved this phrase, have loved, in particular, the image of some moustachioed cad scuttling to a Montmarte street corner with a bunny in his arms and depositing it there before scarpering at his date’s approach. To brush shoulders with you felt just as silly, but also as joyful.

So here I am, having just consciously literalized a phrase, and I glance behind me, to my husband, to whom I am pledged partly because I believe he would never check his phone during a performance of Music for 18 Musicians. I look to him all flushed with my triumph, to check and see if he just witnessed this event, but he’s not looking at me. He is instead, doing the exact same thing: I see his eyes lowered with concentration as he shifts slightly to the right, a minuscule movement, but sufficient to ensure his right shoulder makes contact with your right shoulder as the two of you pass. And the moment it’s happened he looks up, meets my eye with a grin, and that grin says, “look who I just brushed shoulders with!”

Leandro Fresco & Rafael Anton Irisarri, "Un Horizonte En Llamas"

Everything will be better and this time they mean it.

If we make it to tomorrow we’ll see the sun again, they say, but they tell you a lot of things that never turn out to be true — or, if they are true, they’re never as good as they promised you. Maybe the weekend will be amazing! Maybe once we get past this day it will be summer from here on out and soon our only complaint will be that it’s too bright and the weather is so warm all the time. Maybe all the nations of the world will join together in peace and harmony and we will all raise our voices to sing the planet’s traditional anthem of friendship, Quad City DJ’s’ “C’mon N’ Ride It (The Train).” Maybe! But I’ve been burned so many times before I’m just going to expect darkness and gloom and be pleasantly surprised if things turn out in any way otherwise. Okay, enough of me. Here’s another track from that terrific Leandro Fresco/Rafael Anton Irisarri collaboration. Enjoy.

> Coconut balls, and other things the presidents ate

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

There is a cookbook on our cookbook shelf at home called Arrow Rock Cookbook.

It’s from a historic preservation organization based in Missouri, and in a little mission statement in the opening pages they say they wanted to record recipes from some of the country’s foremost “hostesses.” Our copy is from the (early) Reagan administration.

It contains the usual mid-century and ‘70s-era recipes, and women’s names are followed in parentheses by “(Mrs. James Thurgood Jr.)” or whatever because no one could apparently recognize who they were without the context of their husbands’ names.

But the most interesting part of the cookbook, for me, is that it has tons of recipes submitted by wives of presidents.

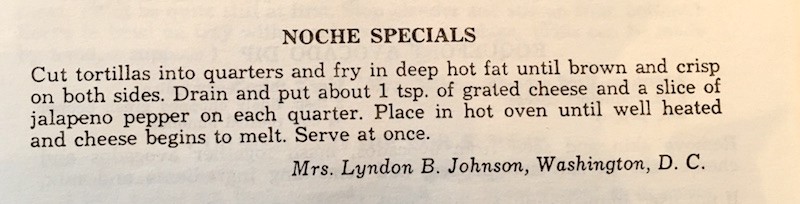

So what do presidents eat, other than noche specials which sound kind of delicious to be honest?

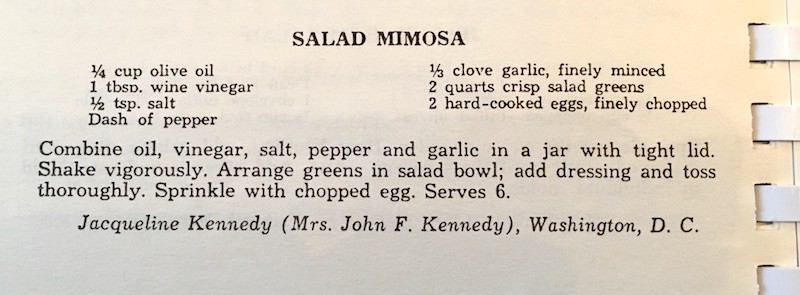

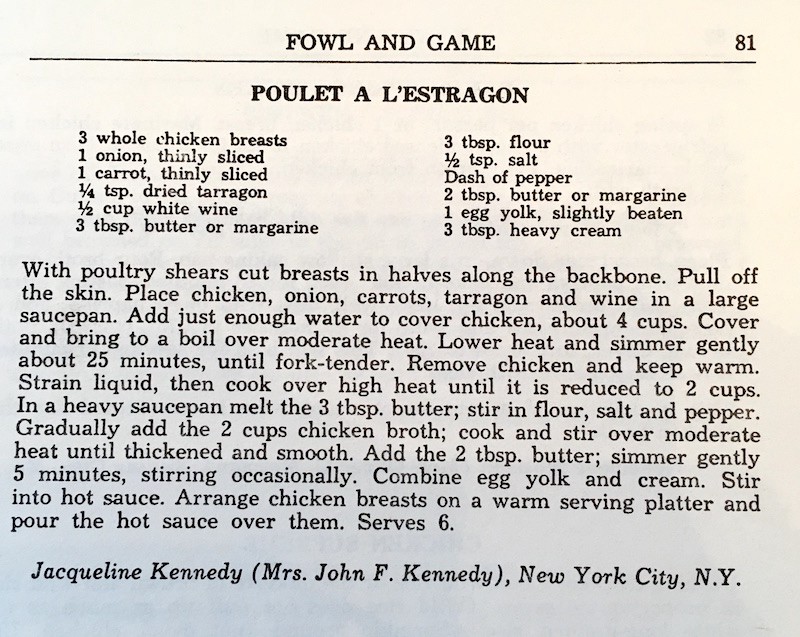

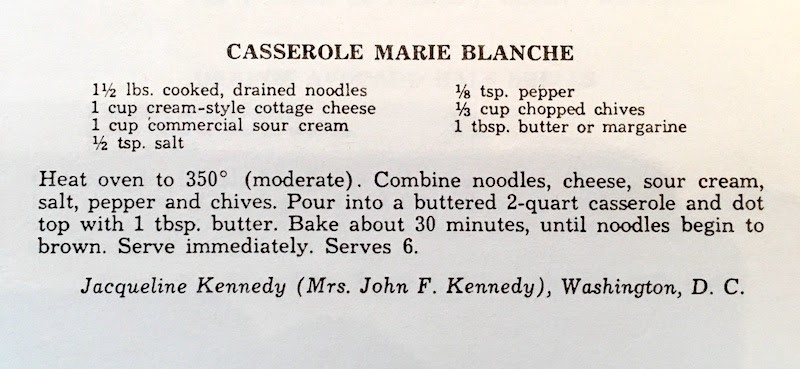

French or French-adjacent dishes for JFK and Mrs. JFK.

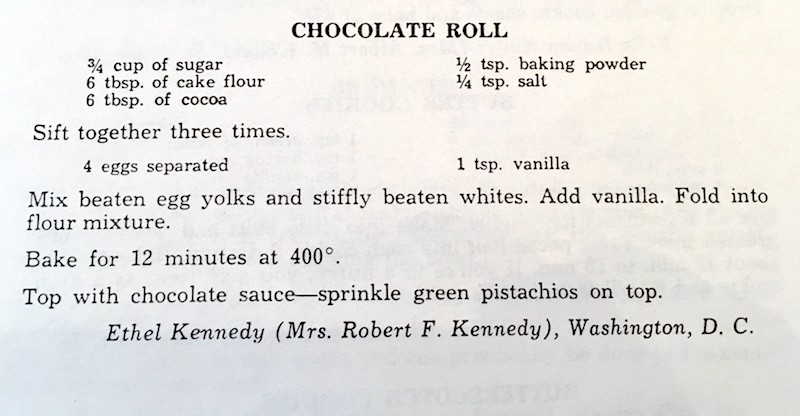

Their sister-in-law makes something called a Chocolate Roll that I think I will try making this weekend:

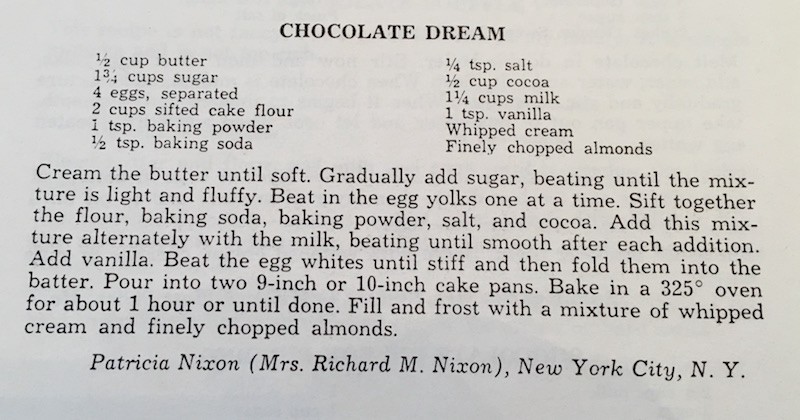

Mrs. Richard Nixon lives in dreams:

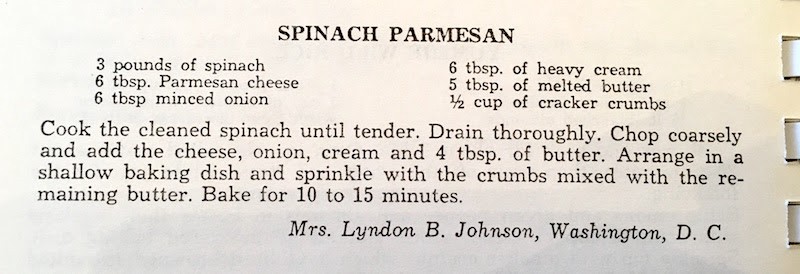

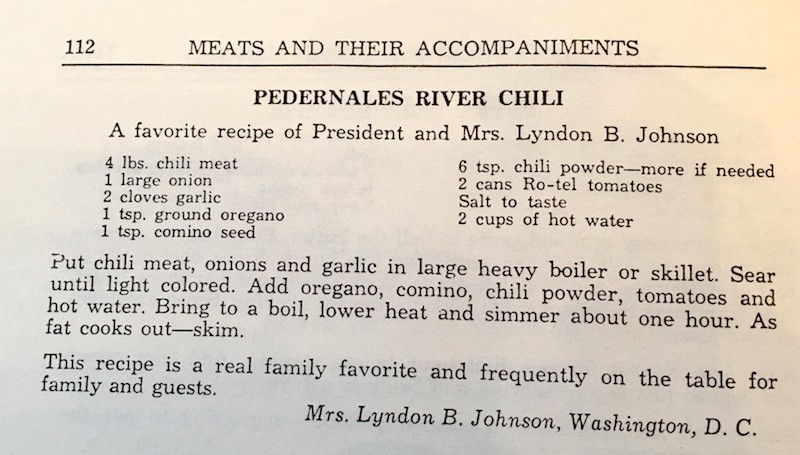

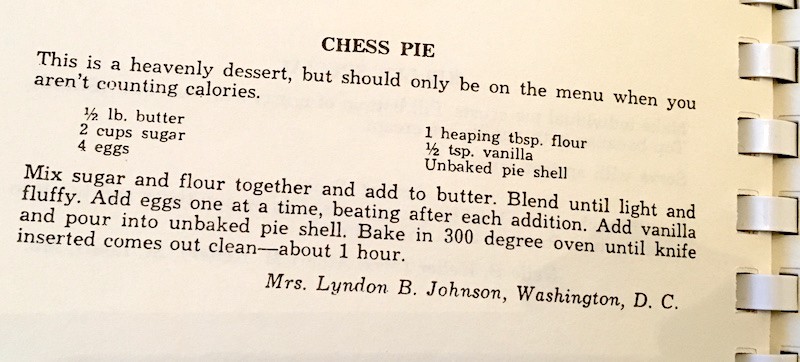

Lady Bird and Lyndon B. Johnson like cheese and meat and chess:

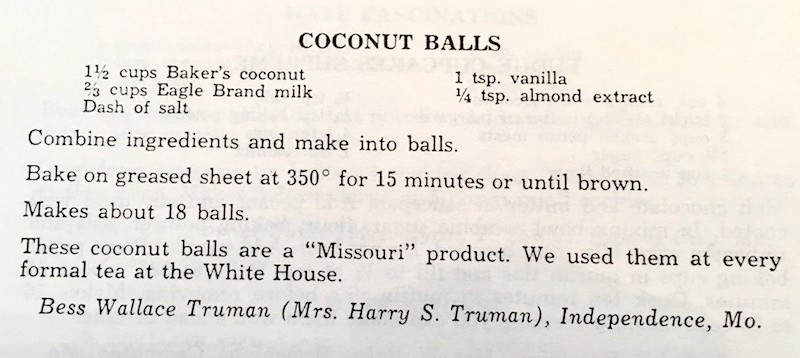

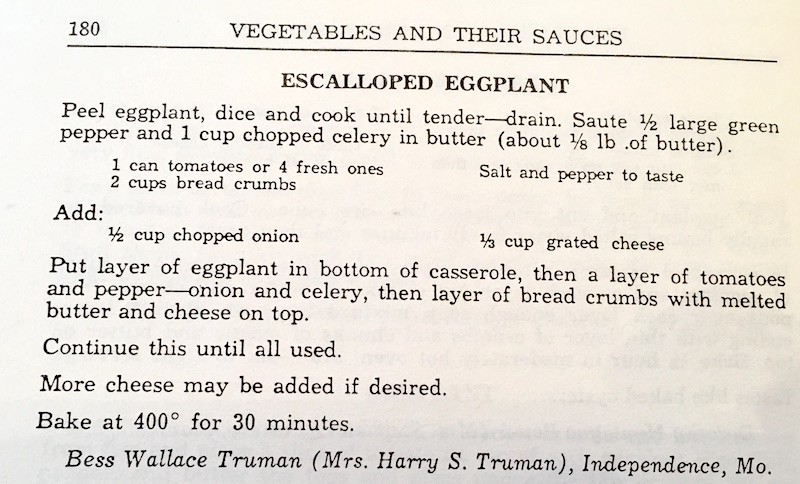

Coconut balls and eggplant for the S Trumans:

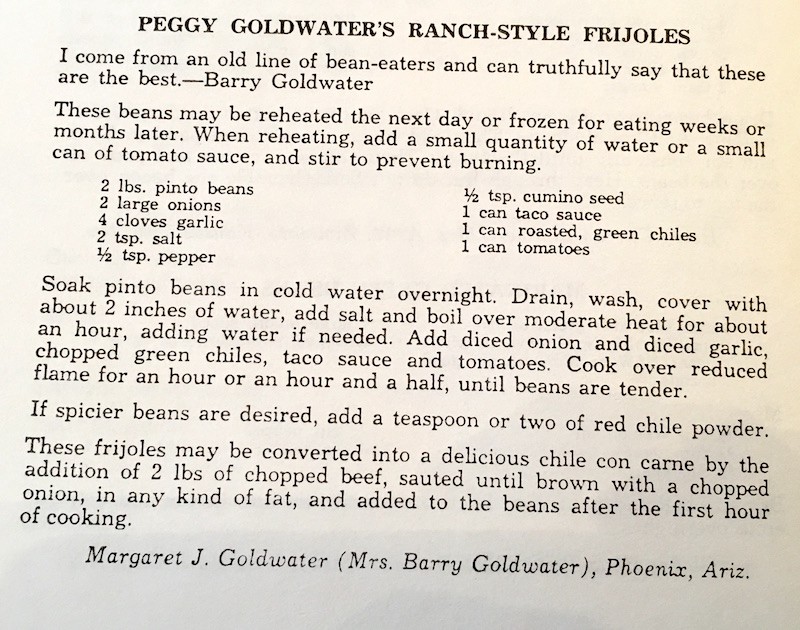

Barry Goldwater and Peggy are “bean-eaters”:

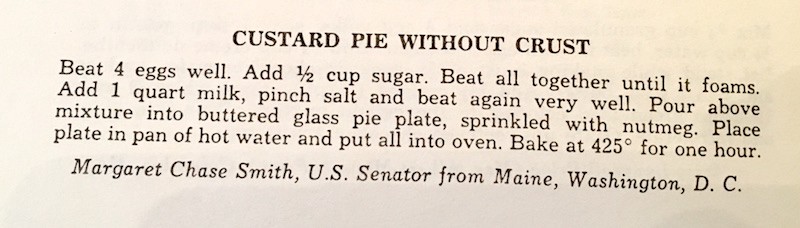

And finally, Margaret Chase Smith doesn’t need a parenthetical — or a crust, thank you very much.

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

Eleven Weeks Later

A reflection in verse

Life staggers you with mystery and not a lot makes sense

The questions are as massive as the obstacles intense

Why even bother loving when both love and loved one die?

How can you face the future when the present makes you cry?

Where should you search for comfort when true comfort can’t be found?

Why would you keep on struggling when you end up in the ground?

But here’s the greatest wonder, with no answer I can see:

We gave this guy the fucking bomb? How fucking dumb are we?

New York City, April 5, 2017

★★★ Light broke through in the sky but the river remained lost in a blurry brown fog, as if the bottom of the new day hadn’t loaded properly and needed to be refreshed. The five-year-old had to be talked out of wearing shorts, and he then looped back to suggest trading his glasses for sunglasses: “But it’s sunny outside. A little.” The schoolyard was in a frenzy; a tennis ball was being fired in long ballistic throws over the heads of the children. Kindergarteners wheeled and sparred. There was fog in the east, too, confusing the growing daylight. What had presented itself as the sun’s inevitable triumph became a cloudy rout at noon. Not till deep in the afternoon did unimpeded blue shine down. The walk to the subway was the clear-lit picture of what would have been a fine day if it had happened on time. Even then there was a murkiness in the west, till suddenly that dullness swelled with a gaudy pink glow and its shapelessness resolved into intricate, illuminated textures.

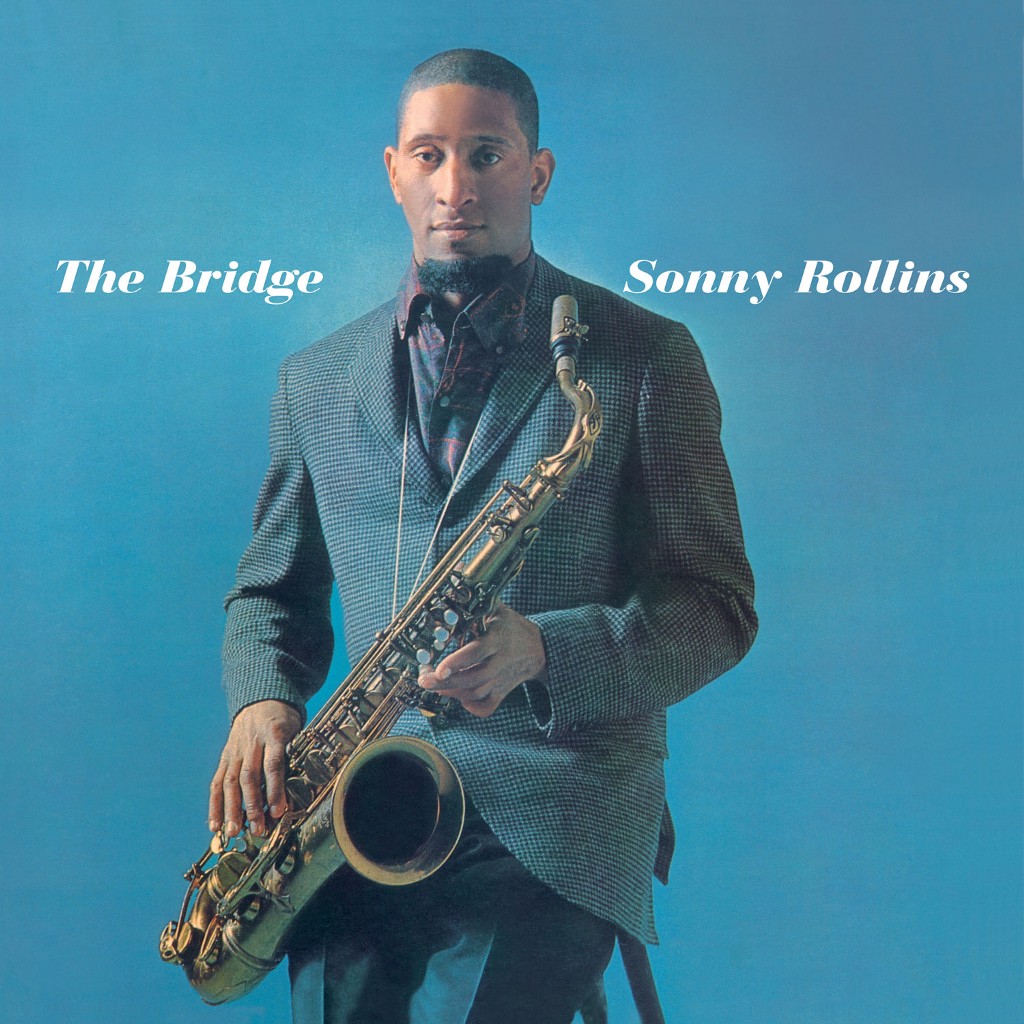

The Sonny Rollins Bridge

If we don’t do this soon some future mayor will name it after Bloomberg instead.

The idea of renaming the Williamsburg Bridge after Sonny Rollins is so beautiful and apt that it will of course never happen, but it’s still nice to imagine. And however many times you hear the story of Sonny on the bridge you are always happy to hear it again. Whenever you’re ready, spend some time with this:

A Quest to Rename the Williamsburg Bridge for Sonny Rollins

And if you’re pressed for time, the man himself discusses it briefly at the end of this clip. Listen now and then read the piece above at your leisure.