I Broke Up With Writing (And It Feels OK)

by Bethlehem Shoals

I’m torn on advice. Sometimes you’re given some and it matters right there on the spot. Then there’s the advice that sits alongside pathetic life-as-lit, lit-as-life devices — think fantasies of watching your own funeral or accurately narrating your life as it unfolds. This is the kind of advice that, either in the moment or as memory, arrives perfectly formed and quotable, a single well-turned line that turns your life into a teaching tool for all humanity. And then there’s the advice that slips by unnoticed at the time, that you cull meaning from only in retrospect, out of metaphysical necessity. How did I get here, anyway? Someone must have told me to do it.

This year, I discovered a new form this slippery, if useful, devil can take: advice that is no advice at all. We all want cues, validation, and support as we make our way through that perilous thicket of choices that is adulthood (there’s not much need for it before, when decisions tend to follow the responsible/irresponsible binary). But sometimes, you take a leap without any encouraging shove. You move forward as if you knew exactly what you were doing and why you were doing it, when really, there’s nothing but hot air propelling you. If that.

Enough with the abstractions. In 2011, I became a father; in 2012, I decided to give up freelance writing for an honest job in the world of advertising. It’s not like I surrendered my soul for a cubicle in the nearest accounting firm. I still get to think up weird shit for a living and the place I work is hardly a button-down police state. Plus, I was never an ace with reporting and frankly, coming up with laudatory campaigns for athletes is probably closer to my strengths than that all-elusive “features writer” status was. The fact remains, though, that at the drop of a hat I gave up the only thing I’ve ever been particularly good at, the only gig I’ve ever really known, and the source of pretty much anything I’m known for outside of my immediate circle of friends and family. I don’t have time to write and if I so much as touch the topic of sports, all sorts of potential conflicts of interest crop up. It’s a strange transition to make — one day, I’m working on another book proposal, then suddenly it’s in the rear-view. I helped found The Classical, which specializes in the kind of thoughtful writing about sports I’ve always valued most and now I’m effectively off my own pet project.

I don’t feel like I fell from grace, though. Anyone remotely acquainted with the realities of publishing — especially for those of us who sprung up from the muck of blogs and other online writings — can see why the wind might have blown me in this direction. When the last few rounds of meal tickets were passed out, I wasn’t on the list. The phone wasn’t ringing, I stink at pitching editors, and really, I was driving myself insane trying to get by on seasonal work and a slew of web pieces that, if you added them all up on a good week, might — might!

— be enough to get by. The thrill was gone, something had died inside, and when a job in advertising came along, I was especially receptive. At that point, I could just as easily have been swayed by the right cult or elite armed force recruiter.

There’s really no regret or anger here; nor does it require you give a flying fuck about what I did qua writer. The fact remains, this kind of career shift (quasi-retirement, dashing of long-held dreams, whatever) feels big to me. I did one thing, in an all-consuming way, and I turned away from it. The part worth mentioning? It just sort of happened. There wasn’t any dramatic consultation with my very first mentor. My agent was happy for me. I scarcely felt torn. I don’t remember any particular argument made for (or against) the move. And, asshole that I am, I barely checked in with my wife about it, even though it required us moving all the way from Seattle to Portland. I guess I was exhausted, disgusted, and even then looking without quite being aware of it for whatever next thing came along. There was no rational process or emotional tug-of-war. It was more like an invading army had landed and I was glad, not heartbroken, to welcome them. It took me several months to really explain to my Classical cohorts what had happened. I still haven’t made a point of explaining the situation to the people who kindly contributed all that money to The Classical over Kickstarter, where I was the principal cheerleader.

Actually, there was one particular conversation, with a journalist I respect immensely, after I had already signed the paperwork to join the agency. Twitter is the ultimate place to attract attention without ever risking much personal investment; that’s pretty much how I let people know that I was now out of the freelance game. She responded to my tweeted announcement, and, after a few emails, we got on the phone. I explained my situation and how little writing was working out for me. She talked to me about potential leads on work and feelers she could send out on my behalf. I eventually had to explain that this was a done deal; maybe, I joked, I should have been even more of a squeaky wheel all along. She continued, unabated, to ask me if I would consider such-and-such gig. I said yes to many she mentioned. And then a funny thing happened: as she went on mentioning different opportunities, I started to turn the conversation toward my own private list of complaints, including the kind of grudges that any longtime professional knows better than to name. That wasn’t the point of this call, and we said goodbye a few minutes later.

No one ever got in touch with me about the gigs she’d mentioned, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised to learn that this journalist never put my name forward for them. Anyone who listened to me talk about freelancing for more than thirty seconds could figure out that, through whatever combination of objective conditions and my own highly personal interpretation of those conditions, I had poisoned that particular well for myself. Maybe not out in the world, but in my head: I had turned the field into something that no longer felt particularly enjoyable or promising. Was that call my bit of wondrous advice? If so, it wasn’t something I didn’t already know. Instead, it was like a mirror held up, one that reflects inevitability back at itself — no questions asked, no alternative seeming present.

Previously in series: What Is This?

Also by this author: The Condition: Chronic Self-Disclosure

Bethlehem Shoals is a copywriter at Wieden + Kennedy in Portland and the founder of the Twitter account @freedarko.

What Is This?

What Is This?

by Jessanne Collins

Around this time last year, I jotted a couple of notes-to-self on hot pink sticky notes and tacked them over my desk. “Feel less guilty,” one read. And: “Read more current events.”

I was content enough with my vague resolutions, but then something, dare I say?, ironic happened. On New Year’s Day I was browsing e-books in a trance, trying to distract myself from feeling guilty about how little of The Economist I’d read. Before I knew what had happened, l had purchased a book called Mindfulness.

It was as if some stifled part of my psyche was using my Barnes & Noble account as a Ouija board to tell me something. It was the last day of a blissfully quiet holiday staycation, which I’d spent reading and writing and knitting and taking long walks by the water, avoiding Manhattan and drinking Manhattans. A stark contrast to the chaos of “real life” which was looming the next morning.

In real life, I spend most of the day, day after day, in a self-induced trance. These days amount, alarmingly quickly, to weeks, and months and years. It’s a defense mechanism, and I blame it squarely on Herald Square. Twice a day, five days a week, I heroically traverse the sidewalk space in front of Macy’s and its clusterfuck of pedicabs and and teenagers and European tourists and tabloid hawkers and shabby Elmos — and, just yesterday!, a man-sized red-and-white fish sprinting inexplicably around the roasted nut vendors.

The only way to not go crazy in Herald Square is to turn your brain off and leave your body. This is make-it-or-break-it territory. I’ve lived in the city for years, but only in the last couple, since I assumed this commute, have I begun to seriously wonder WHY!?!??!?!?!

It was becoming one of those crises that was threatening to reveal me for who I actually might be: someone who punches innocent jerks. I think it had occurred to my subconscious, the thing I entrust to get me across the street in one piece, that something had to give, that something had to give, and as it wasn’t going to be Macy’s, it was going to be my outlook.

Two weeks later, I’d read maybe half the book and abandoned it, along with that Economist subscription. But in the meantime, I’d downloaded some meditations that accompanied it to my phone. I started listening to them a couple of times a week on the train: returning to the breath, making peace with the moth-like thoughts that flitted around ceaselessly in my head, being “here now,” and “letting go.”

The meditations are led by a guy with a British accent, a deep soothing cadence strikingly similar to the Geico lizard. They’re full of maxims and blank space for breathing and gentle reassurances. One of my favorites is the one in which he probes me to ask “What is this?” We’re addressing sensations and feelings, especially distracting, uncomfortable ones. The back crick, the stomach knot, the uneasy feeling of something un-,under-, or mis-said. But it also applies to what’s going on outside. Everything I avoid for lack of ability to eradicate it. (And where to begin!) The lizard advises that I confront whatever it is with curiosity, rather than ignoring it… or punching it.

Gentle, yet persistent. Cute, if a little cloying. It’s his little green voice that’s been echoing in the back of my mind.

“What is this?”

It’s a jackhammer. Tragic news. Guilt. Some misfiring neurons. An ogling pedicab driver. A cat sleeping on a blanket in the park. A tourist. A teenager. A teenager. A teenager. A tourist. The Empire State building with its confetti crown of camera flashes. A tourist. An inopportune hangover. A creepy-ass Elmo. A fat baby in a hat with ears. A patch of pure blue sky in that tiny swath between buildings. Tragic news. That Christmasy nut smell! Very severe weather. A jackhammer. A truly blissful macchiato. A door.

Previously in series: The Only Way Left To Be Radical In America

Also by this author: My Summer On The Content Farm

Jessanne Collins is managing editor at mental_floss. Photo by Jay Santiago.

The Only Way Left To Be Radical In America

The Only Way Left To Be Radical In America

by Rachel Monroe

I like to plan ahead, so by the time I turned 30 earlier this year, I was already preparing for old age. I have a problem with rounding up, is the thing. When I was 27, I’d read about a 39 year old who went bankrupt, or a 45 year old who had a hard time conceiving, and think, Well, I’m practically 45, so I should probably start inuring myself to the hard truths life has in store for me.

I understand that this is ridiculous. I’m not old; I’m older. And of course “old” doesn’t necessarily mean what it used to. My parents are getting oldish (sorry, Mom) — enough to qualify for discounts, at least — but they also run half-marathons. My grandfather’s blog is pretty cool, even though he hasn’t updated it in a while. My dad just told me a story about crashing a party at Art Basel. Sixty is the new twenty-five!

None of that makes me feel any better; it terrifies me, in fact, because I didn’t much enjoy being twenty-five, and I don’t want to go to more parties. My daydreams of the good life involve fewer parties, actually, and not blogging, and feeling safe in my body, and never worrying about having enough money. So as long as I never get any older and figure out how to get someone to pay me, I should be fine. But instead I keep having birthdays, and my life gets more and more precarious. In my darkest moments, I think of old age as just a frailer reliving of early adulthood: a time when the world insistently reminds you how incapable you are of taking care of yourself. You know how no one takes you seriously when you’re twenty, and you have to eat ramen all the time because you’re poor? In my mind, being old will be like that, but sometimes also you’ll break your hip.

Or worse, even — old age will be the country of retribution, where everything I thought I’d gotten away with — eking by without things like, you know, a “career” or “benefits” or “financial stability”; breaking up with men who were very kind to me; preferring cats to children — will come back to haunt me. This visitation will happen in some sort of nightmare fashion that ends with me dying alone, probably in a shack, my cats nibbling on my corpse. I imagine old age as payback island, the unfun vacation home of imposter syndrome, where all those risky adventures and courageous, life-affirming decisions will come back and show themselves to have been the wrong risks, the wrong choices. You can only get away with this for so long, my future crone-face hisses. What, did you think you weren’t going to have to pay?

Which is why the best advice I received all year was actually a short piece of video art by poet/artist/general badass-about-town Stephanie Barber. In it, an oldish lady stares at the camera, blinking occasionally. She looks like she knows a secret. She’s wearing nice lipstick. It only lasts twenty-two seconds, but it feels longer — this extended, steady close-up shot of her face. Meanwhile, words flash up on the screen, one by one: THE ONLY WAY LEFT TO BE RADICAL IN AMERICA IS TO BE OLD. The woman’s face stretches into a grin. Her earrings sparkle.

I saw Stephanie at a party the other day. She’s been hanging out with older ladies recently, she told me — painters in their 70s, elderly art professors. She thinks that old is the new punk. Old is the new punk! It felt like a revelation; I’d been thinking about it wrong the whole time.

I’m not the only one who’s gotten old people wrong. While the microgenerations and niche subgroups of youth are relentlessly documented and marketed to, the old are allowed to glide by, undifferentiated. They’re allowed to be in movies and TV, but only if they’re sex-obsessed and/or filthy-mouthed — behaving like the young, in other words. “People are increasingly treated as if they’re invisible as they age,” Psychology Today frets, but aren’t they forgetting that invisibility is a superpower? Old people can be mean, or have ridiculous hair. No one’s mining their tweets to better sell them things. Who do they have to be afraid of, anyway?

And so in 2013 I vow to spend more time hanging out with weird, lonely, happy old ladies, either by reading their books (May Sarton; Dorothy Day), or inviting myself over to their houses on the pretext of being helpful. I will pay close attention to everything that Patti Smith does. I will not buy expensive retinol creams. I will live precariously for another year. I will round up not in fear, but in anticipation. Soon enough, I hope, I’ll be old and punk and invisible and broken-hipped and indestructible.

Previously in series: Don’t Stop Running

Also by this author: The Killer Crush: The Horror Of Teen Girls, From Columbiners To Beliebers

Rachel Monroe is a writer living in Marfa, Texas. Video “To Be Old” by Stephanie Barber, used with permission.

Don't Stop Running

I have never been a physically daring man. I’m afraid of heights such that my palms begin to sweat when I go up high flights of stairs in shopping malls. I’m awful at skiing, made slow and hesitant by an unyielding and morbid fear that I will propel into a tree or somehow shatter my femur in a devastating tumble. In middle school, when I joined the football team, in an attempt to realize my father’s thinly veiled desire that I be a quarterback, I was decidedly not one of the star players. To be very good at football, you need to be able to snuff out the voice inside of you that says it’s better for everyone if you do not hurtle your body at great speeds into another person’s body. I couldn’t squelch that voice, which only got louder after I watched a massive and overeager boy named Ryan bend my friend Mike’s leg the wrong way during a hitting drill, breaking it in two places.

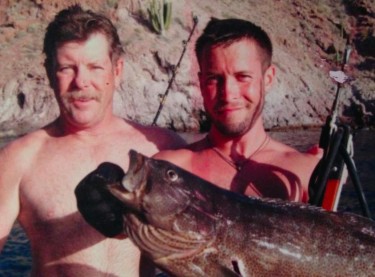

Some people don’t have a voice urging reticence and caution. My friend Chris doesn’t, largely due to the influence of his father, Leo. Leo grew up in Tucson, Arizona, which at that time wasn’t even the mid-sized strip-mall Mecca it’s become today. Though in many ways he’d had an average middle-class upbringing, Leo’s father was an abusive alcoholic, prompting him to move away from home and get his own place as soon as he could put together enough money, which he earned laying pipe for a construction company. He married his high-school sweetheart, a half-Japanese woman with permanently rosy cheeks named Martha, and soon they were having children. Chris was first, and then his sister, Kelle.

When I met Leo, I was about six or seven. Chris and I went to the same elementary school and had become close quickly (“I think black people are funner and funnier than white people,” he once told me excitedly after we first started hanging out). We ended up enrolling in the same karate class so we could spend even more time with each other. His mom or dad, whose house was near our school, would drop us off, and my mom would pick me up later.

I remember being in awe of Leo, a short but solid log of a man, partially because of how different he was from my dad. After working as a pipe layer, Leo hauled scrap from construction sites for a living, while my dad was a lawyer. Leo, with his bushy handlebar mustache, usually wore jeans and work boots, while my dad favored pressed slacks and a clean-shaven face. Leo drove a pickup truck, and not in the way guys in big cities who want to play cowboy drive pickup trucks. Leo’s truck was caked in mud and scratched and dented, a victim of the abuses people and things receive in the desert, on dirt roads, around horses, around large men building things with their hands. My dad drove a Saab.

What I appreciated most about Leo, and what was most different about him from my parents, was how much time he spent in the outdoors. My father once said to me, “All the camping I need to do in this life I already did in Vietnam”; my mother, while lovely and doting, always preferred a bridge game to a fishing rod. I grew up a child who found many of my most enriching experiences indoors, in front of a computer or a book or a movie. For that reason, Leo’s stories about his far-flung wilderness adventures were exotic to me, stirring a curiosity deep from within, as if I were listening to an alien describe a cocktail party on the moon.

Besides pictures of his children, Leo’s walls were embellished with mounted heads of deer and javelina (small desert pigs) he’d killed with arrows and bullets, and then gutted himself. He angled on lakes and streams and the ocean, sometimes fighting for hours to reel in fish that were roughly the size of human babies. When mere rods grew tiresome, Leo would throw on snorkeling gear and leap into the water to fish with a spear gun. He skied on snow and water, and he scuba dived. Once, not having the slightest idea how to sail, Leo bought a small sailboat anyway and made Chris accompany him on the vessel’s maiden voyage. For half a day they got thrown haphazardly around a lake in northern Arizona by gusts of wind neither of them knew how to navigate, eventually capsizing the boat and having to wait for the only other boat on the water to come and rescue them. But tenacity prevailed, and by the time dusk began to settle on the painted rock formations ringing the water, the novices had become a halfway passable skipper and first mate. Soon thereafter, Leo was signing them up for sailing races in Mexico.

It’s impossible to be raised in such an environment and not emerge with a siren’s song in your guts and heart pulling you toward adventure and danger. From my father I took, among other things, a love of jazz and an affinity for wearing loafers with no socks. Chris took from Leo the desire — nay, need — to push his life to the limit. Besides sailing boats and going fishing and going hunting and all the other things Leo taught him to do, Chris builds and rides motorcycles; rock climbs, occasionally in the middle of the night; hikes the mountains around his house in Tucson; and cycles the softly sloping and winding roads that stretch out into various corners of the endless Arizona desert. To accomplish all of his various activities in a timely manner, Chris will occasionally demand his friends stick to a rigorous schedule — “Up at 8 and out the door by 8:30” and that sort of thing. He calls this “being a Leo.”

Chris, with his love of exploration and impulsiveness, has grown to be my closest traveling companion over the years, and thus, not incidentally, the major balancing offset to that cautious voice in my head warning against risk and bodily injury. Chris is the guy who, after spending all night barhopping in Budapest, demands you climb out the hotel room’s skylight and dangle your legs off the roof. Chris is the guy goading you into leaping from your hotel balcony to your passed-out friend’s hotel balcony in order to sneak into his room and obtain an iPhone charger. Chris is the guy driving his motorcycle 80 miles per hour five feet away from a sheer cliff drop on the Croatian coast. In late 2011, I ended up staring off a 50-foot rock looming over the Adriatic Sea in Dubrovnik. Below was Chris, who had already jumped and was now treading water while screaming at me.

“Just fucking do it!” he shouted. “Don’t think about it! Everyone’s staring at you! Aren’t you embarrassed?”

Knees shaking, I leapt, assuming the ocean floor would surely crumple my legs like breadsticks when I plunged through the water and hit it. But I came to the surface fully intact and trembling with nerves and involuntary laughter. Chris was beaming.

“Good job, buddy,” he said. “I didn’t think you were going to do it.”

“Were you scared?” I asked.

“I don’t really get scared,” he said. “And if I do, it’s already too late.”

With that, he kicked his legs and dipped his head underwater. Still shaking, I watched him swim a bit farther away from shore.

There is something about living life ultra-spontaneously — and some would say on the edge of reason — that is unshakably and clearly linked to death. I asked Chris once to what he attributes his dogged pursuit of thrills, what motivates him to walk on the edge both figuratively and, while prowling atop the roofs of Hungarian hotels at four in the morning, literally, too. “I’ve done everything I ever hoped to do in this life in just 30 years,” he said. “From here on out everything is icing on the cake until I die, and that makes me feel good.” I never asked Leo the same question, but I imagine he’d say something similar, although for a different reason.

Something many people didn’t know about Leo, and something I didn’t know until this year, is that he sometimes suffered through periods of serious depression and paranoia, buzzards that would appear and circle ominously over his otherwise charmed and charming life. Things got especially bad when his once successful trucking business, which at its peak was earning him six figures, began to flounder during President Obama’s first term. Leo started to believe it was Obama’s “socialist” policies that were ruining his small business, despite the fact that Chris’s own small business, a salon he’d opened in 2007, was flourishing. He begged Chris to not vote for Obama again, and, though he, Martha, and their children were all completely financially stable, he worried that he was not doing enough to provide for them. His mania eventually started to take over his whole life, drastically altering his behavior. In 2010, Leo, who had for decades welcomed me into his home and showed me very real love, was dragged out of a wedding by his humiliated wife after calling President Obama a “nigger” to an appalled group of Brits from the groom’s family.

At the end of February this year, Chris’ cousin, John, a cop, came out one morning to find Leo sitting in his car with a shotgun. “I wanted you to find me,” he told him. “I couldn’t have Martha or the kids find me.” John rushed Leo to the hospital, and later that day Chris went back to his childhood home to remove all of Leo’s guns from it. At the hospital, when the doctor asked Leo what was bothering him, Leo began, “Well, it all started when Obama got elected…”

In March, Chris and I decided to fly to Brazil for a vacation. I was in the midst of a frustrating patch at work and he thought some time away could help him clear his head of anxiety about his dad. We ate a lot and drank cachaça like mother’s milk. In Paraty, a cobblestoned colonial town that once served as a slave and sugar port, we rented a water taxi to take us to a restaurant on a sandbar. After we ate, we paddled a pair of kayaks to a tiny island populated only by rocks, some bushes, some cacti, and a few elongated and elegant birds that seemed totally indifferent to us. I remember looking down into the water, whose rich and layered darkness signaled some infinite depth, and feeling like I hadn’t done anything so important in months or years or ever. Cacti in the middle of the ocean, I thought. Imagine a thing like that.

We flew back to Los Angeles through Lima, Peru. We were sunburned and road weary, but still lightheaded the way you get when you’re coming coming down from shrugging off responsibility for a week or two. I hugged Chris goodbye at LAX, where he had to wait for his connecting flight to Tucson. I kissed him on the cheek and told him I was proud of him, and I told him I’d see him soon. A few hours later, while struggling to concentrate at work, I got the phone call from a friend: While Chris’ flight home was still in the air, Leo had hanged himself in his office. Several days earlier, Leo had tried to overdose on pills, but nobody told Chris for fear of upsetting him on his trip. After that, family members had been watching Leo in shifts as he fell deeper and deeper into depression. But he was determined, and he took advantage of a few minutes he found between Martha’s departure for work and his father-in-law’s arrival for the following watch. In retrospect, Chris says that he remembers detecting a certain tone in his father’s voice when he Skyped his family from Paraty one night. He says that in the back of his mind he knew his father had decided it would be the last time he was going to tell his son how much he loved him.

Some days I think perhaps the reason Leo stormed into life with such ferocity is because he thought something that was chasing him was gaining on him, and that when it caught him it would blot him out, eclipsing him and casting him into a darkness from which he would never emerge. Maybe he thought, just as Chris had that night that he was saying goodbye to his dad forever, that the end was coming for him much faster than it was coming for the rest of us, and that’s what led him to run so swiftly and eagerly in the opposite direction. If that’s the case, I wish he had known how many of us had been running with him and cheering him on.

Four days after we’d arrived in Brazil, Chris and I decided to go hang gliding. We took a cab down to a beach where a Google search had told us gliders congregate and, after 15 minutes, $100 dollars, and a few hastily signed release forms, we were in cars headed to the top of a mountain with two men who spoke hardly any English. The language barrier made it very difficult to understand even basic instructions about how to hang glide, with my handler, Paulo, saying only, “Just run, guy. Don’t stop running.” By that, he meant that I should not hesitate when it came time to run off the cliff. This is what Paulo’s English and my Portuguese were too poor to illuminate for me before we’d begun our ascent: To get a hang glider airborne, you stand about 40 feet from the edge of a cliff and run off of it at full speed.

The same voice that had paralyzed me years before on the football field once again crept up my stomach and into my throat, and I told Chris I didn’t think I could go through with it. “It’s not natural,” I said. “It makes no sense to deliberately fling yourself off a cliff.” Chris laughed at me and smiled the way he always does when I tell him about some fear that’s gripping me at that particular moment. And then, as he always does, he channeled Leo, whom in that second was thousands of miles away and probably far more scared than me: “Just jump,” Chris said. “And if you die, you died fucking hang gliding over Rio, so who cares anyway?”

In the end I ran, I jumped, I did not die, and I now think of the incident fondly for providing me with two of my favorite bits of advice this year: “just jump” and “don’t stop running.” If used figuratively, those vague enticements to action are the stuff of cloying motivational posters. I like to take them literally, however, and repeat them when faced with the physical feats that have always terrified me, preventing me from participating fully in this thing or that. In May, staring down a new cliff to jump off of in Hawaii, for once I didn’t hesitate when it was my turn to dive. That time I didn’t even need Chris, who was at home with his family, to yell at me and tell me that, though our bodies and minds are fragile, it is not a requirement to always treat them gently. There can be beauty found in calculated recklessness, and, for some, even clarity of purpose.

In 2013, I look forward to taking more grand leaps. And if my body should break and be killed on the rocks below, I hope I can be like Leo was and summon the courage to make the most of the fall.

Previously in series: Why You Should Not Use Twitter For Corporate Customer Service: A Cautionary Tale

Also by this author: The End Of The 00s: Family Business

Cord Jefferson is the west coast editor of Gawker.

Why You Should Not Use Twitter For Corporate Customer Service: A Cautionary Tale

Why You Should Not Use Twitter For Corporate Customer Service: A Cautionary Tale

by Lindsay Robertson

Last spring, my first in a new apartment, I was careful to order my air conditioner way ahead of the first heat wave. I picked out a window unit from Home Depot online and scheduled delivery for a Friday in mid-May that I’d chosen as a spring-cleaning vacation day.

That morning, I woke up and looked up my order online, only to see that it had been suddenly (I’d checked the day before) back ordered and wasn’t coming for nearly two weeks. I was furious! I would not be one of those people who didn’t have an air conditioner when it got hot outside! I had done everything right, and I deserved my air conditioner. This wrong needed to be righted.

So I did something I hadn’t tried before but that I’d been advised by friends and the internet to do in such a situation in such times as these: I addressed my grievance directly to the company on Twitter.

After all, nobody who was following me could even see it unless they happened to also be following @HomeDepot, and why would anyone do that? As far as unfortunate displays of entitlement went, it was the perfect crime. They wrote back right away.

Wow, it worked, I thought, and work it did. An extremely polite and apologetic Home Depot rep at their headquarters called me throughout the day to update me on every tiny step in the Search For A Comparable Air Conditioner in the Tri-State Area For The Honorable Super-Special Miss Robertson. Finally, they located one, way out in the furthest-from-me reaches of Queens, and asked if they could deliver it later that night.

Close to 11 p.m., the buzzer rang, and I went downstairs to let in not the burly delivery guys I was expecting, but an older man and a petite middle-aged woman, who struggled to carry the heavy 8,000 BTU unit together up one flight of stairs. Shocked, I quickly figured the story out: these visibly exhausted people were store managers, who had already worked all day and had nothing to do with the company’s online error. And I was the reason they had to drive from Queens to south Brooklyn in Friday night traffic for this errand instead of being home with their kids. I thanked them profusely and awkwardly handed the woman the $20 I had in my pocket as a tip, and they left.

I closed the door and ran to my front window and looked down at the street as the two co-workers got back into the car, which was a regular car, not a Home Depot truck. It was clearly the personal car of one of them. It had New Jersey plates. They still had a long way to go before they got home that night.

I burst into tears.

That night I got ready for bed in the shadow of a huge box representing the Pyrrhic victory of my social media experiment. I felt everything one might feel after completing the exact opposite of a random act of kindness. It’s true that, had I known I would ruin someone’s day, I would have gone through the usual channels and ended up waiting for my air conditioner the way we all did before social media. But that’s not the way it worked out.

So, yeah: the lesson is to think really carefully before doing something like that. That includes using Twitter to jump the line when your flight is canceled for weather reasons, as I saw a friend with a huge number of followers do a few weeks after my own Twitter disaster. I wanted to tell him what I’d learned: it’s just not worth it. Wait your turn, like everybody else, like we all learned in elementary school. It’s much more satisfying in the end.

Unless the corporation you’re going after is Time Warner Cable, in which case you should use every tool available to you to take those f-ing mobsters down.

Also by this author: How Not To Die Of Rabies! A Chat With Bill Wasik And Monica Murphy

Lindsay Robertson Tweets about her hatred of clutch purses here. Thumbnail photo by Rupert Ganzer.

One Ring To Rule Them All

One Ring To Rule Them All

As Polly Esther, The Awl’s existential advice columnist, Heather Havrilesky gives advice in this space every Wednesday. Here’s an excerpt from her memoir Disaster Preparedness about a bit of advice she once received.

“Find someone early, don’t wait!” My father’s thirtysomething girlfriend leaned across the table to deliver this advice in a stage whisper. I was only nineteen years old, and my father was within earshot. But Alice had tossed back a few glasses of red wine and she was winding up for one of her soliloquies. She didn’t have kids (not that she didn’t want them!) and she needed to save me from the same uncertain fate.

“Really?” I stabbed my steak with my fork, hoping she’d see how little I felt like discussing this in front of my dad.

“Yes, really.” she said, sitting back in her chair. “When I think about the great guys I dated in college, guys who would’ve married me in a heartbeat? Jesus…” She trailed off, looking over at my noncommittal, 50-year-old professor dad who was polishing off his halibut, hardly listening to her words.

I studied Alice across the table. What was wrong with her? She was reasonably attractive, smart, opinionated, and she seemed to like drinking. She was anything but boring. Maybe she was too demanding or too bossy and she went on and on about herself? Maybe she seemed confident on the outside, but once you got to know her she was insecure and needy and got teary at the drop of a hat? There had to be some reason she was dating a man 15 years her senior, a man who clearly wasn’t about to marry her or give her the babies she wanted. Sure, my dad was good-looking and successful, but he also juggled much younger girlfriends far and wide, including one or two in Europe, to visit when he gave talks abroad. “One girlfriend, or three,” he told me once. “But never two. If you have two, they’ll find out about each other, and they’ll be pissed.”

This was the sort of pragmatic advice my father bestowed: advice that made no sense (three girlfriends wouldn’t find out about one another somehow?), advice that had nothing to do with me.

My mother was even less helpful, limiting her counsel to some vague assertion of my appeal as a person, while inevitably managing to cast doubt on that appeal along the way. When I had a problem with a boyfriend and needed her input, her response was, “Who cares? If he’s not interested, I’m sure someone better will come along as soon as he’s gone.”

“Who said he’s not interested?”

“I’m not saying that, okay? I’m just saying it’s irrelevant. You’ll always have men eating out of your hands, no matter what you do. Why bother with someone who’s lukewarm?”

“Who said he’s lukewarm? Is that your impression?”

“Heather! Jesus! I’m just saying, there will always be lots of men who are interested in you, so why get hung up on someone who’s on the fence?”

And so it went. Any practical discussion of whether this particular boyfriend was on the fence or not was out of the question. It didn’t matter how much I said I liked him, or how much I wanted it to work. It was beneath my mother to mull whether this or that guy liked me or not, and it was beneath me, too. Why couldn’t I see that? She preferred to look at the big picture — I was a catch, damn it! — and ignore the little day-to-day bumps in the road. She wished I would hurry up and do the same thing.

My dad preferred the big picture, too. “All men are assholes!” he’d announce, almost gleefully. “Never forget that.”

“You’re a man.”

“Yep. That’s how I know.”

But instead of looking at the big picture, instead of casting a suspicious eye on the guys around me, instead of knowing that for every lukewarm asshole in my sights, there was another asshole waiting in the wings to take his place, I wondered suddenly if I shouldn’t nail down one particular asshole as soon as humanly possible.

After all, to hear Alice tell it, while college was a fertile paradise, teeming with virile young men anxious to settle down and start earning money to support their beautiful wives and darling babies, post-college life was a barren wasteland, populated by lecherous middle-aged divorcés who wouldn’t so much as lend you their bus pass after a night of hot sex.

So in keeping with Alice’s very practical advice — the only practical advice I’d probably received about love in the first 19 years of my life — I spent the next 15 years hoping to marry every single guy I dated.

I wanted to marry the ambitious but slightly shallow yuppie who knew way too much about expensive wine for a 21 year old. I wanted to marry the stubbornly childlike aspiring filmmaker who thought marriage was a bourgeois trap designed to damn otherwise spontaneous people to lives of mediocrity and silent longing. I wanted to marry the older divorcé who lounged around the house in MC Hammer pants, quoting his favorite passages from Conversations with God. I wanted to marry the balding, perpetually unemployed stoner who had a life-size cutout of the Emperor from The Empire Strikes Back in his bedroom. Instead of assuming that there would always be attractive, interesting men around, I adopted Alice’s scarcity mentality. I stretched out each relationship well past its natural shelf life. I remained committed despite big flaws and major incompatibilities.

Even so, like the school principal who’s determined to stick with even the hardest cases, I had impossibly high standards of behavior. I tried each boyfriend’s patience to no end. I was fault finding and relentless: This is not how the man I’m going to marry should act! I’d try to redirect his behavior, using polite but explicit terms. Hmm. How can I inform him, nicely, that my future husband should not talk about the wine at great length, or say things like “My mama didn’t raise no dummies — except for me and my brother!” or wear MC Hammer pants? How can I make it clear that my future husband should mention how pretty I am much more often? How can I make it plain that my future husband should ask about my day, then listen like his life depends on it?

Every step of the way, no matter how frustrated I became, I never realistically evaluated our differences or made a rational assessment of our inability to move forward as a couple. I thought each guy constituted my one last chance to nab a husband before I lost my looks or resorted to dating middle-aged swingers. I just had to make this one work, there was no other option.

***

The irony was that, right before Alice delivered her little speech, I had just broken up with the perfect guy, the ultimate future husband. Henry and I fell in love the first day of college. We stayed up late every night, listening to music and making out and marveling over how perfect we were for each other. He was unbelievably cute and he was crazy about me. He hung on my every word. He couldn’t wait for his parents to meet me. He raved about how incredible I was, how much he wanted to spend the rest of his life with me. On Valentine’s Day, he got me a huge heart-shaped box of chocolates, a necklace, a teddy bear, a heart-shaped balloon, and a dozen roses with a card that said: “This is what it’s all about.” I wanted to be caught up in the moment, but I couldn’t quite tamp down my skepticism. “Really?” I thought. “This is what it’s all about? Valentine’s Day? It’s all about buying a bunch of red crap for your girlfriend on a manufactured consumer holiday?”

But Henry was a romantic. He could get whipped into a state of almost hysterical sentimentality over any little thing: a walk through campus, a trip to our favorite BBQ joint, you name it. There was music playing in his head. He was at the center of his own little romance novel, and I was the ravishing lead with the flowing hair and heaving bosoms spilling out of her bustier.

College life isn’t kind to romantics. That spring, as I reveled in the joys of drinking cold beer with rooms full of cute, flirtatious upperclassmen with broad shoulders and deep voices, Henry confessed that he sometimes worried that I would get bored and break up with him, sooner or later. “No, no. That’ll never happen!” I told him immediately.

Then I thought, “I’m going to get bored and break up with him, sooner or later.”

That fall, just as Henry had predicted, I became fixated on a mercurial guy named Finn. Finn would ramble on about highly personal stuff whenever he got drunk (which was often) — his relationship with his father, his ongoing existential crisis. He was smart and very intense and could talk for several hours straight, always viewing the world in alienated, suspicious terms. He seemed a little depressed and whenever he sobered up, he couldn’t remember any of our conversations.

I became obsessed with Finn. How could I resist? Henry was totally dedicated to me. Finn barely even noticed when I was in the room. Henry wanted to spend the rest of his life with me. Finn was liable to pass out or wander home with some other girl at any second. Henry listened to my every word with great concentration and focus. Finn could hardly focus on my face.

So I dumped Henry. He was depressed for months. He wandered the hallways of his dorm at night, weeping audibly, keeping all of his friends awake. The breakup was tougher for me than I expected. I missed Henry, and didn’t realize how much I’d derived my happiness and confidence from his presence. There was only one thing to do: follow Finn around until he agreed to go out with me.

Eventually, Finn and I started hanging out regularly, but we were never officially dating. There were no flowers on Valentine’s Day, no cards singed your best friend always and forever, no mix tapes with sentimental titles featuring sappy songs by Don Henley, no long phone calls. I just showed up where I knew Finn would be, and at the end of the night, he’d ramble on about himself as we walked to my dorm room together. Unlike Henry, who was always worried about the tone of my voice or what that look on my face meant, Finn hardly noticed anything about me. But he refused to discuss whether or not he was on the fence about me — this talk was beneath him. He had bigger, more existentially pressing fish to fry — just like my mother did! When he woke up hungover and saw his pale face in the mirror, he called himself an asshole — just what my dad would’ve called him! In other words, while Henry felt unnaturally positive and warm, Finn felt like home.

Also, he was really tall and he didn’t listen to Don Henley.

This is how your mind works when you’re 19. But once I had that awful conversation with Alice, I was tortured, because why was my future husband getting wasted and puking into that trash can, then flirting with a random woman he just met by the keg?

Even so, this pattern continued for years. I rejected relationships with stable, genuinely interested men to go out with lukewarm, inappropriate, unavailable, self-involved, off-kilter mutants. It would be unfair to call them assholes. Most of them were nice guys, guys who could easily make a less demanding woman very happy, guys who I made pay dearly for their future-husband status. And even as they pulled away, I became more determined to imitate what I thought a fulfilling relationship should look like: I prattled on endlessly about the farthest reaches of my emotional landscape, analyzing and unpacking past experiences, unleashing a torrent of what I thought were hopelessly charming anecdotes, escaping into rambling monologues on the unacceptability of patchy facial hair or pug dogs or insupportable fashion trends. I figured I deserved to loom large, to confess every detail of my history. I thought I should be accepted and embraced for everything I felt and thought, for everything I’d ever felt and thought before. I figured I should be celebrated and adored, like some kind of a demigod.

In other words, I was a lukewarm, inappropriate, unavailable, self-involved, off-kilter mutant. Maybe this was the glue, the common ground that kept me and my so-called future husbands together.

Yet, inevitably, each future husband would decide that he would prefer not to be my future husband. This took longer than you might imagine — somewhere between 18 months and two years in most cases. Often, I was forced to end the relationship myself, but not without provocation: Typically my future husband had proclaimed his total unwillingness to be my future husband several times before I finally relieved him of his duties.

This pattern finally shifted the night that my last so-called future husband, Dave, returned home from an East Coast trip. During an expensive welcome-back dinner (I was buying, of course), Dave described telling his friends (and their happy, baby-flanked wives) how I was ever so anxious to get married. He told them I had become despondent when I didn’t get an engagement ring for my birthday. He related this story to me cheerfully and matter-of-factly, munching away the whole time.

Of course he was right. I’d wanted an engagement ring for as long as I could remember — from anyone, really — but that’s not what had made me so upset on my birthday. I’d been annoyed because he ran out to the drugstore that morning and returned with a copy of Finding Nemo (because he loved that movie!) and then asked me for some wrapping paper to wrap it with. That was not how my future husband should act, was all.

I was horrified. My boyfriend not only got me a crappy animated movie for my birthday, but he turned around and told all of his friends that what I really wanted was a ring! Then he had the audacity to tell me about it.

“So . . .” I asked, willing myself not to lose my cool right there in the restaurant. “What did Ellen and Ava and Rebecca say?” I needed to know what the wives, with the babies on their hips and the adorable toddlers running around in their four-bedroom houses, had thought about this.

“They said you should dump me,” he replied, stuffing his mouth full of fish. I looked down at the untouched salmon on my plate, and suddenly it dawned on me: This was not how my future husband would act because this was not my future husband! This was just some balding, unemployed comedy writer, eating a good dinner on my dime. Hot damn, why was I even having dinner with this guy?

But I didn’t say another word. I got up and walked out of the restaurant, and sat down by a fountain outside. It was time to take the very practical advice offered by these wives, albeit secondhand. It was time to look at the big picture. I was 34 years old. I would always have men eating out of my hands, I told myself. I tried to picture myself at 65, old and gray, surrounded by fawning men, all of them chowing down on grilled fish.

Dave came outside, sat down next to me, and smoked a cigarette. I told him that he should move out. He finished his cigarette, and we went back inside and finished dinner.

I wish the story ended there, with me the picture of grace and self-restraint, silently moving forward alone, but that’s not my style. Instead we returned to the house we shared and I cried for at least an hour, and then, surrounded by a pile of snotty tissues, I proceeded to deliver a series of lengthy treatises on my utter desirability as a future wife, including some extended musing on the totally unthinkable, insane notion that anyone, let alone someone with a full-size cut-out of the Emperor in his bedroom, would willfully turn his back on the prospect of marrying me, glorious me, wonderful me, hot mustard and me, me!

Let’s face it, if you have to expound upon your countless qualities as a future wife, you might as well just staple bologna to your face and screech like a wild bird. Making a strong case to a man about your viability as a prospective wife is about as wise as informing your current girlfriend that you know that she’s going to dump you, sooner or later. I think that’s what my mom was trying to tell me, years before, but somehow it took me 20 years to figure it out.

***

When Dave moved out, I was Alice’s age. Was there something wrong with me? Yes. I was attracted to indifference. I settled, and then tortured my boyfriends for it.

At age 34, it was way too late to find someone early, as Alice had strongly recommended. I figured it was probably too late to find someone at all. I decided I would just have to adopt a baby on my own eventually. In the meantime, I’d get a few more dogs. I would work on my songwriting. I would write a novel or two. I would paint the rooms of my house weird colors. I would be messy and odd and interesting, the sort of woman who didn’t worry about what men thought, at long last. I’d be the sort of woman who knew that men would always be interested in her, but didn’t particularly care either way.

This dog-lady vision was comforting to me, somehow. And soon, instead of telling men I met that I was the perfect catch, I started to tell them the truth, based on what my ex-boyfriends had told me over the years: Like Alice, I was reasonably attractive, smart, opinionated, and anything but boring, but I was also very demanding and way too bossy and I went on and on about myself sometimes. Furthermore, despite appearances, I was insecure and needy and got teary at the drop of a hat.

That fall, I met someone new. He was smart and handsome and thoughtful and funny. Even though I was tempted to gloss over my flaws a little, I told him the truth. I warned him that I was impatient and demanding and emotionally overwrought and sentimental and earnest and exasperating, and I could be a serious pain in the ass.

“So, in other words, you’re a woman,” he said.

And I thought, That’s exactly what my future husband would say!

Previously in series: Say I’m Alright

Also by this author: 3 Tired TV Tropes & 3 Shows That Toppled Them

Heather Havrilesky is The Awl’s existential advice columnist. This excerpt is reprinted from DISASTER PREPAREDNESS by Heather Havrilesky by arrangement with Riverhead, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc. Copyright (c) 2010 by Heather Havrilesky. Photo by Taryn.

Say I'm Alright

by John Wenz

So this is the story of how, this year, my friends pushed me in a big direction with the advice to go back into therapy, get back on medication and stabilize my life.

First, a little background: I have struggled with periods of intense depression since high school. In college, I began to seek help. After a period of prescription missteps, the diagnosis began to shift. What at first appeared to be depression complicated by anxiety issues revealed itself to be something else entirely: Bipolar disorder, with all its peaks and crashes. High clarity and uncontrollable energy followed by a plummet into days or weeks of utter despondency. I was put on mood-stabilizers as a result, and stayed on them for roughly three years.

But then a couple years ago, I found that I’d quit a job with a salary and benefits in D.C. to return to Nebraska to… work at a race track for 15 hours a week. It was a strange decision, and it sprang partly from wanting to get out of the culture of D.C., partly from wondering if I was meant to be back at home near my family, and partly, let’s be honest, from being lost. The track wasn’t all bad — but as a sole source of work, handing tickets to bettors for $8 an hour wasn’t enough for me to get by. I couldn’t afford my mood stabilizers. And though assistance programs exist, I couldn’t find a public health clinic to help me get a prescription for said programs. So I cut up my remaining pills and tapered off as best I could.

As time went on, I feigned fineness, even as I withdrew from my friends, fearing some judgment (unspecific but damning) on the current condition of my life. A roommate urged me to get back on medication. “You are all right sometimes, but sometimes you really do need it.” Her voice trailed off as she waited to see how I would react. It might be with a burst of anger, or a bout of shame — who knew with me then? I would sometimes get incredibly paranoid and defensive and distrustful. But I shouldered it, saying, “I’m fine, and I’m better off without it.”

A change of scenery was what I needed, I decided, not help. I’d left the race track and joined a state health office in the communications department. But now I quit that job and joined an AmeriCorps program in Philadelphia, cutting my income by 2/3rds in the process. Surely if I felt that if what I was doing had some purpose, it would stabilize my emotions.

It didn’t. I spent the AmeriCorps year miserable. I made a failed attempt at retrying therapy. When the three free sessions provided by my health coverage ran out, I was kindly offered a reduced rate by the therapist. But instead I chose to run away from the sessions. Throw myself into the volunteer tax program tied to my AmeriCorps work. At this time, I was hardly seeing any friends — I’d alienated many of them. I was paranoid, uncommunicative, mopey, asocial. I was alone — and I felt I deserved it. And at the same time I also, oddly, thought I was getting along quite well. When a college friend asked me how I was managing, I claimed I was using coping mechanisms. But those coping mechanisms involved listening to sad music in my room with the door shut and the lights off trying hard to avoid confronting anything outside of it. Any attempt to concentrate on work was thwarted by my brain slipping into a frenzied inability to concentrate for a moment. It felt like I was staring into the grand abyss.

I was finding myself unable to cope with the day to day, often spending hours just staring off into space and doing nothing of value. It was getting bleak and hopeless feeling. I called every psychiatrist’s office I could, seeing if they accepted the health plan I was on. Most often, they didn’t. I was getting unhealthy and my friends were past wary. Most of my talk revolved around self-loathing. But eventually, I managed to find a psychiatrist who would take me and resumed a course of medication. And I gradually improved. But upon getting a job post-AmeriCorps and managing to lose it within three days due to a “lack of enthusiasm,” I crawled back into a deep depression. I would spend days, unshowered, staring at job listings or trying to beat decade-old video games, spending my nights listening to “We Are Fine” by Sharon Van Etten on repeat.

The medication wasn’t enough. And so a friend began to prod me to start talk therapy again. To find some solution. She was, by her own description, a pushy person — wanting to prod people to what they needed, being stubborn with any push-back. As my self-appointed Jewish Mother, she laid down stern instructions about me finding a job again. That I needed to leave the house to do it and not just apply online. My brain, still acclimating to the new intake of psychiatric drugs, couldn’t process it yet; still paranoid, I saw her advice less as a sign of care and more as an ultimatum.

I found a job as a short order cook, but still she prodded. I needed to do more than just make rent and bills, she said. I needed to do more than just survive from day to day. It wasn’t enough just to be medicated. What I needed was real help, real talk therapy, she kept repeating. And a second job to be able to afford that, which I found.

I returned to my old therapist, who was still willing to work with my uninsured self at a low rate — chump change, really. I was seeing him once every two weeks. In our sessions, we’d discuss what was happening currently as well as some troubling issues in my past, finding in the investigation a more concrete root for my insecurities, and how they informed either side of my brain — suspicious paranoia and racing elevated thoughts, or the slow torpor of crushing depression.

One of the friends who had pushed me back to therapy had recommended a book to me, Why Be Happy When You Could be Normal? by Jeanette Winterson. In it, Winterson reflects on the negative voice in her head. “It was worse than having a toddler. She was a toddler, except she was other ages too, because time doesn’t operate on the inside as it does on the outside.” Yes, I thought, when I read that. It’s like living that, with a brain full of tantrums and taunts and guilt. “Whatever she was, she wasn’t going to therapy. ‘It’s a wank, it’s a wank, it’s a wank!’”

But it was in therapy, I found ways to “other” the negative reflections handed to me by my brain, to ignore its toddler tantrums and fits. Also, it helped to talk about things the past, to have some root reason that anchored the passing fears and insecurities.

And recently, just a few weeks ago, my therapy session ended early. Instead of using the full time, the session came to a close early, serenely. No teariness, no yelling, no sitting in the park afterwards trying to decompress. I was on track, and I could see it. I’d found a job that fit the pace I needed in order to feel effective, and I’d found ways to at least work on fulfilling the needs of the rest of my life. As I spoke to my therapist, my problems seemed trivial — or in progress. I was working through them, without letting them defeat me.

It’s still not perfect. I’ll still be in therapy. But in being in it, I’ve managed to feel like I’m living again. I understand the nature of my illness, that I will still live with its symptoms and cycles, as well as the moments where a day feels like a loss. But I can write it off and go on to the next day.

And it’s a place I wouldn’t have been in had not my friends advised, cajoled, pleaded and demanded that I take care of what had weighed on me for so long, that I work on being what I can be.

If you’ve found yourself in a place like this, you are not alone. If you have friends telling you to get the help you need, it is because they’re your friends and they care about you. And by all means, do the best you can to seek out and find ways you can afford to do it. Because you may not realize it, but the world you live in inside your head isn’t always the way the world is — it’s affected by internal forces just as much as external ones. And if your brain is telling you that everything is shit, that’s not always the truth of the matter. Breaking yourself of the mindset can make that clearer. Sometimes it requires the footwork to find those magic words, “sliding scale,” but in the end, it’s worth it. So very worth it. That is the best advice I got this year — and the best I could turn around and share.

Previously in series: David Mamet, Fairy Godmother

Also by this author: My Attempt To Make The Perfect Nebraska Runza

John Wenz is a writer living in Philadelphia. He’s doing better now. Photo by Katy Warner.

David Mamet, Fairy Godmother

David Mamet, Fairy Godmother

I don’t get enough advice. Maybe it’s because I spent years actively ignoring it? This year I was hoping for some good advice, and still am! No matter how well you’re doing, there’s always a sense that you’re dogging it, and there’s some bit of wisdom that will push you through the membrane of the day-to-day to untold fabulousness. A foolish thought to carry around with you, but there it is. However, while waiting for my fairy godmother to clobber me with a toaster, calendar 2012 was a year that I kept going back to the greatest advice I ever got: Never open your mouth until you know the shot.

It is an extraordinarily useful bit of prescription, in dealings both personal and business. Obviously, it deals with being circumspect, with keeping confidence. If you aspire to being a person who other people confide in, then the trick of that is not betraying those confidences. Everyone loves a good bit of gossip (in fact, entire industries are run on it), but if you are a person that discloses such tawdry business, then people will not share it with you anymore. Hence, keep your mouth shut. This applies to your loved ones and personal affinity groups, and to whatever career you find yourself in. I personally am employed in the legal end of the greater entertainment industry, where this sentiment is not just a good idea but rather the law, and of the few insanely interesting things I may or may not know about people who may or may not be famous, I can’t tell you any of them. That is why my company gets paid.

But it’s not just a recipe for being closed-mouthed (and this is why I kept coming back to it this year) — it’s also staggeringly apt as an instruction when you are in the process of learning things you do not know. When in a situation that you desire to acquire a skill, be it snaking a clogged sink or writing a novel of certain American greatness, shut your fool mouth. Find someone that knows this skill, plop yourself down, and don’t speak. Consider the skill the shot that you do not know. Do not betray ignorance or eagerness. Stop thinking of yourself entirely. Just plop. And after a fashion of keeping your mouth shut, you will find that you are actually paying attention, and whether through instruction or plain observation, you have just tricked yourself into learning.

The origin of this, as you may have guessed, is not from an mentor or parental type. It is a line from David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross, and it’s spoken by the character Ricky Roma (played in the 1992 movie by Al Pacino) to the character John Williamson (played by Kevin Spacey). The set-up is that the hot-shot salesman Roma is trying to sweet-talk a cold-foot customer by assuring him that the deposit check hadn’t been put in the bank, and office manager Williamson, misjudging the bluff, assures the client that it had been deposited. (It hadn’t.) So Williamson gets dressed down, in a not unfamous monologue, and that line is the second-to-last, followed by, “You fucking child.” “You never open your mouth unless you know what the shot is,” is the actual line of dialogue. I shortened it. It’s prettier and more portable, and I guess I have an unconscious prejudice against the dangling participle. And I prefer until over unless because I like to think of the shot as a thing that will be known and not might not be known.

Of course it’s a bit troublesome, the current Dennis-Millerization of David Mamet notwithstanding, taking a line from a play, a line spoken by a character who is a prototypical asshole, and ascribing use to it. As in, that’s the best I can do? And I didn’t get it from the movie. A couple years before the movie, I was in a largely reverse-gender production of the play in college. I played Williamson, so the girl that played Roma, a Chicagoan adept at swearing, hissed the line at me repeatedly through a month’s rehearsal and the handful of productions. It sunk in. Ridiculous? It’s done me well; I’ll take it.

The act of writing this is naturally a contravention of the rule. I am decidedly not keeping my mouth shut, and I do not pretend to know the shot. But the best advice is unasked for, it falls in your lap and you wonder what it is. Sometimes it takes a good long time for it to evince itself, or for you to realize what a gift you’ve been given. Sometimes you actually have took one in the face from a toaster wielded by the fairy godmother. You just didn’t know it at the time.

Previously in series: How To Be A Good Author

Also by this author: What It Cost Eight Women Writers To Make It In New York

How Should An Author Be?

Writers have contorted relationships with publishers, probably because they excel at projection. Particularly this is true now in an age where publishers sue writers for undelivered manuscripts. Something about this has the ring of the disinheriting vengeful father, if you’re paying half-attention, until you snap to alertness and realize that it’s just a business that wants its money back.

There are writers who dream of selling books, the kind who when they were little children for some reason fantasized about having bound books with their names upon them. No one dreams, yet, of having an .epub file with his name in the metadata. (Or does someone? Who knows yet what the monstrous children of the millennials desire!) Why people want things is so strange anyway. Then there are writers who would be regarded as more mercenary, those who architect their careers and manage household finances with the repeated selling of books.

A publishing house has sometimes-conflicting goals inside itself. Editors get credit for acquiring both “good” books and “successful” books and, reasonably, get extra credit for a twofer. For their part, publishers do love writers. But that is like loving a wayward child, or an alcoholic. Writers are, in the aggregate, charming, manipulative, secretive, sometimes violent. Mostly they are awful. They are not so different from your average real estate broker or dentist in this way.

If you’re the sort who is interested in the question “how to be a good person,” then it stands to reason you have considered the related question, “how to be a good author.” You can serve either of the impulses of the publishing house. You can certainly write The Four-Hour Sadomasochistic Sex Life or its next iteration (Trampires, Inc.). Or you can write something more ethereal, marked distinctly to be something that gets equal and quiet portions of praise and scorn in “the literary journals.” (Which I guess now are The Millions, the LA Review of Books and the comments section of HTML Giant.)

The obvious thing we are told and that is also true is that most books are not often read.

Most books reach an audience of a few thousand in their first year. And then there’s no telling what happens to a book over a period of 100 or 150 years. From Herman Melville — who could barely turn a dime, no matter how much he wrote — to Walt Whitman — self-publishing self-promoter extraordinaire — to Henry James — frantic and frustrated magazine hack, who sometimes had serial novels running simultaneously in competing journals — publishing history both recent and ancient shows that what remains standing and in print would likely come as a shock to those writers’ contemporary book-buyers. While these men were extremely commercial-minded, it’s still true that if someone from back then got in a time machine and went, for whatever stupid reason, to a bookstore to see what still existed now, mostly they’d be like, “Oh, her???”

After I sold a book a few years ago, which I did in equal parts because I was broke and because it was something I hadn’t tried before and therefore seemed like a good idea, I was left with that question, of how to be a “good” author. (N.B. The word “author” is kind of gross to me but here we are. When people ask me what I do for a living, I tell them “I work as a writer,” or sometimes I mumble something about “the Internet,” and all that’s only because I don’t want to be all, *flips ascot back, removes monocle* about it. Answering this question opens one up to being a huge asshole! ANYWAY. Glad we had this talk.) Obviously I wanted to be polite and helpful and good-natured, as much as I could be. But how did I want to interact with the business of publishing? I could, likely, write something on the shocking side of commercial, the kind of book considered palatable but just enough outrageous to get some attention. (It could have some sort of “trick”!!!) Or I could write something quiet and little and pretty, something determined to be proudly not “playing a game.”

These perhaps are questions that many book people do not consider, it should be said. My shortsightedness in general is that I am over-obsessed with the commercial systems of our time, not that I’m very good with engaging with them except as an observer. It seems clear to me that money is a game. In New York, especially, money gets passed around for little coherent reason. I am always seeing those paths — paths I have watched people (writers and painters and lawyers and everyone else) take over and over again — that are forged with some canny choices and some elbow grease that results in, at least, a short-term windfall. And then I like ignoring the obvious lessons.

I talked to a number of writers early, while I was working on and thinking about this book problem. (Through no fault of my own; mostly that is because they all have things to say about this and so offered their opinions.) They all did have helpful things to say and really each had a working theory about How To Be. One person in particular, though, was a writer who had the most astonishing and hostile feelings toward the publishing system. I couldn’t understand why he was engaged with it at all, and I suspected that he was a misery to work with. But I admired it. He had something: as a writer, he was like some embattled Central American dictator, burning with conviction. He’d had a novel due for years to a major house, which he has since turned in. The only control in this system that the author has, he told me, is in writing the book that he feels he must write. (He also believed that this control was best exercised by how late in the process the author turned in his manuscript. Terrible! But hilarious. Possibly also true!) But also: the author was not to consider commerce, or the wishes of publishing houses or agents, or current vogues, or the polluting ideas of the outside world. He was only to write the book that occurred to him in those moments — for me, in the shower or too early in the morning mostly — when he was alone and most free.

In the end, I didn’t really get any better advice. The upside of this route is that you later have no one to blame but yourself. You can’t blame capitalism or astrology or what have you. You can’t blame your lovely editor or your agent — fine, upstanding book-loving people! — or your parents or their stand-ins. This most suits me in any event because I was raised in California and am therefore incapable of blaming myself for anything at all. This way, the entire enterprise will be blameless. Even if the product is terrible! Everyone will have done his and her honest best.

There is something about the publication of a book that feels to me like the going to the airport and being manhandled by security and then heading down the long cold lonely ramp until, at last, the book is poured into InDesign or whatever they use now, which is when they slam the pressurized doors shut and then there’s nothing you can do but sit there with yourself. Those terrible headphones are five dollars now! That’s not a metaphor, that’s for real. They used to give that shit away on planes you know. Anyway. Here in the long pre-publication period — this thing comes out in August, 2013 — it’s a bit chilly and lonesome. It would be easy to be riddled with doubt, and then to act out, and I completely understand why people become needy or aggrieved or childish or awful. It doesn’t seem worth it. Ask me again in six months, though, as I hear that the whole process only gets exponentially more harrowing.

Advice: A Year-End Series

Advice: A Year-End Series

by Awl Staff

To keep you company this holiday week and the next, a series of essays (long and short) on the advice (practical and im-) that people took or ignored (or contemplated) this year. It’s The Year In Advice — and it kicks off in just a short while. We hope you’ll enjoy. And our thanks for reading and keeping us company this weird, wonderful year.