New York City, January 14, 2013

★★ The first light revealed rich blue fog, with wet pavement below. Visibility gave out after four or five blocks, where Broadway angled out of view at Verdi Square. The fog lifted into a cool gray morning, but that was as far as improvements would go. The temperature stopped its climb. In the afternoon, up on the rooftop under a sky of rumpled gray cotton batting, it took a long time to realize that there was no acclimation to be had, and that the coolness had become an outright chill.

"The Thetan Templar," A New Novel By Dan Brown

CHAPTER ONE

New York University, Manhattan

11:44 A.M.

Nate “Shirky” Stryker looked over the NYU courtyard beneath his office balcony. There were 32,000 cobblestones in that perfect rectangle, or a thousand for each of the 32 degrees of Islamic-Rite Masonry, an organization that officially didn’t even exist.

Stryker ran his left hand through his graying, dignified temple hair. Beneath him was a galley copy of his next book, Strangled Theories: Why Everything You Know About Memeology Is A Lie. A hot-pink Post-It on the title page said, “Another Million Seller! Fondly, R.M.”

Perhaps it is, Stryker thought. Or perhaps it isn’t. Time would tell, if Time continued its present lateral monodirectional motion. Conventional science said it would. But that’s what conventional scientists always said. Through his storied career as an archeologist, artificial intelligence pioneer and new-media consultant, Nate Stryker had ruffled more than a few feathers … even from his undergraduate days at Yale.

As a professional occultist, Stryker was used to being ribbed by the medical establishment, as well as the jerks down at the physics lab with its then-state of the art small-hadron collider. But even those guys had to give Stryker credit for discovering the so-called X Neutrino, or God Particle.

What a world, Stryker thought. They go crazy over the God Particle and most of them don’t even believe in God. But they will soon. Unless I can stop this.

Under the galley copy was a hatch on the desktop, so smoothly aligned with the surrounding teak that not even Stryker’s darkly beautiful assistant professor, Tanalyne Foster Wallace, had ever noticed the secret chamber before. Deftly tapping his watch face four times, Stryker watched as the hatch opened, revealing an elegantly curved glass dildo inscribed with beautiful Arabic letters. Tanalyne leaned over and Stryker softly inhaled a whiff of her clean, luxuriant hair.

“If this gets to the right-wing press before I’ve had time to warn the Elders,” Nate said aloud, “We’re all going to be facing God.”

The helicopter was waiting on the roof. Stryker grabbed his overcoat and trademark tweed beret from the hat stand that doubled as a rare Egyptian idol of Horus. Looking back on his office, he wondered if he would ever see it again. Not if he was dead somewhere, that much was plain.

But when the tenured professor’s special elevator opened, Nate Stryker knew he wasn’t getting in a helicopter after all. There was no torso, no head, no arms. Just legs. Five sets of legs. Women’s legs, beautiful except for the still-bloody tattoos around the ankles. It was the same Arabic word that was on the ancient glass dildo. There is no exact translation for Bettawfeeq , but Stryker had grown up speaking Arabic, doing graduate work on newly discovered pyramids in Egypt. He knew exactly what it meant: Trouble for the whole planet.

Beneath those new ancient pyramids were thetans, millions of them. L. Ron Hubbard had been right all along. And as long as Hubbard’s templar investigators known as Sea-Org were paying the media to run a smear campaign, there was no chance those thetans would ever burst through the Giant X Particle Accelerator compound deep beneath the nuclear research laboratories of EndCum Systems, the Vatican’s secret space-research division.

Tanalyne opened her Google phone and pressed the scarlet button. After a moment, she checked her Chartbeat account and then closed her clamshell.

“The toenails,” she breathed into the back of Stryker’s neck. Of course. Stryker literally smacked himself in the forehead, literally. Each toe was discreetly and discretely marked, using a Navajo color code now practiced only by the 24 royal members of the Order of the Garter.

They could hear the helicopter on the roof depart in accordance with Tanalyne’s signal. “M…P…” translated Stryker, squinting at the toenails. “R…”

But the wash of the departing rotors blocked out what he said next.

“My God,” Tanalyne said in the eerie quiet, giving her Fendi bustle a shake. “They’re going to pollute the entire social graph.”

But who was “they”?

And now it’s time for Chapter Two.

We'll Die The Way We Lived: The Arcology Dream Is Over

Conservative millionaire entertainer and peddler of conspiracy theories Glenn Beck is building a city-state, “an entirely self-sustaining community called Independence Park.” I can’t wait to visit, it sounds like it will be very welcoming to all kinds of Americans.

He’s on the right track, though. So are the seasteaders. And the gun-hoarding survivalists of all stripes. And those of us who are interested in reviving the New York City Secession Movement. (Our plan is to secede and then, uh, magically raise the city by 30 feet. Still working on details there, do check back.) But yes. The coasts will drown, or the United States will disband, or World War III will come, or the currency will go belly-up, or the NATO black helicopters will take us out, or the squirrels will take over, or some combination thereof will occur in the not terribly distant future.

These concerns inspired the dream of the arcology, which gripped SF writers for decades. A self-sustaining city-state is the simplest way to deal with generation ships, post-apocalyptic societies, climate change and the future of overpopulation, after all. And Mussolini even kind of tried it, with the planned city EUR, so it must be a good idea.

Paolo Soleri gets credit for the term. Since 1970, the architect has been building Arcosanti, which is really more an “experimental town” (an “urban laboratory” in their words) than an arcology. If you’re ever driving from Flagstaff to Phoenix, then 1. definitely stab yourself for doing that and 2. check it out!

Magazines like Wired love to identify COMING-SOON arcologies that are under construction. Or “under construction.” These are all Very Shareable Photogenic Things that the Internet loves. How are all these projects doing? Turns out: not very well. LET’S LOOK TOGETHER.

Arcologies are the province of design competitions. What’s better than a design competition? You get to make some crazy plan, and then, if you’re Zaha Hadid or Norman Foster, you maybe get to build a cool museum or a mildly green train station now and then. But for everything else, everyone on the Internet passes around your renderings, presenting them as news. The problem being: renderings are never news, because they almost never get built. Anyone who’s looked at New York City’s building process in the last 12 years should know that at a fundamental level.

But some arcologies came close. A few even exist! And a few others probably should.

The Shimizu TRY 2004 Mega-City Pyramid

This is “a proposed project for construction of a massive pyramid over Tokyo Bay in Japan. The structure would be about 14 times higher than the Great Pyramid at Giza, and would house 750,000 people.”

Why it doesn’t work: “The proposed structure is so large that it cannot be built with currently available materials, due to their weight.” (Good news: they have lunar base plans too though.)

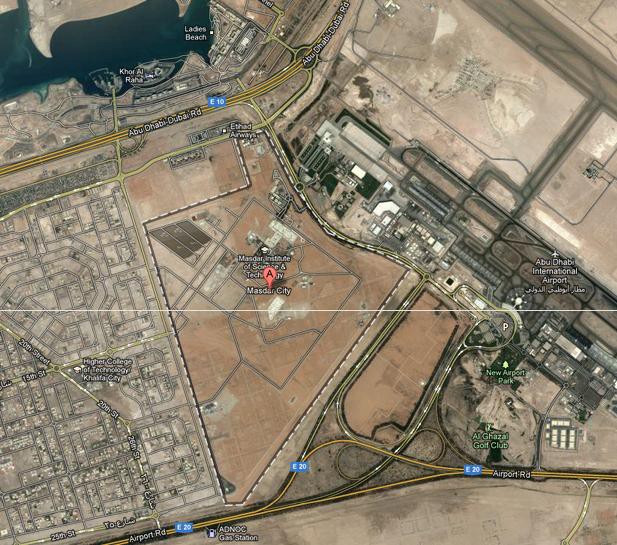

Masdar City

Masdar City, nestled uncomfortably next to the Abu Dhabi airport, is really more of a business demonstration project for renewable energy and for making lots of money. Masdar is a company that is a subsidiary of Mubadala, which is a “wholly owned investment vehicle” of the government of Abu Dhabi. So Mubadala is an amazing thing: a financial firm, an aerospace research and production firm, a healthcare firm, and basically everything else you would shove into one company if you were super-smart and had all of the money and were also THE GOVERNMENT. Mindblowing, right?

So “Masdar City” is actually a special economic zone — while being half-residential at the same time. Why would you put your company there? “The benefits of setting up in Masdar City include 100% foreign ownership with no restrictions on capital movements, profits or quotas, strong IP protection framework, zero per cent import tariffs, zero per cent corporate or individual tax and zero currency restrictions.” Ah.

Even in a country of wild resources, Masdar City has been scaled back: “the final population will probably not exceed 40,000 and the completion date has been put at 2021 or 2025. The idea of a second Masdar City has been dropped; a $2.2bn hydrogen power project has been called off, as has a ‘thin film’ solar manufacturing plant, intended for Abu Dhabi.”

Still, be right back, opening up The Awl Masdar City offices.

Why it doesn’t work: You can’t export the bizarre economy of Abu Dhabi to the rest of the world. Hmm. At least… not yet.

The New Orleans Arcology Habitat

Aww, someone does care about New Orleans. Yes, meet me there for lunch, surely this already exists, right? (Kidding! It doesn’t and it never will.)

Why it doesn’t work: Capitalism. Also probably racism.

Crystal Island

Oh the ballyhooed Crystal Island. The world’s biggest building, everyone exclaimed, back in 2007: “Sir Norman Foster’s mountainous 27 million square feet spiraling ‘city within a building.’” Will this building ever happen? Hmm: “The proposed site for the Crystal Island is a peninsula located five miles from the city centre. Flights into Moscow’s Domodedovo airport bank sharply over the proposed site shortly before landing. “ Oh and: “However construction has not yet begun, and has been postponed due to the economic crisis — whether it’ll start up again remains to be seen.” Spoiler: unlikely. (Not to be confused with Shenzen’s Crystal Island! Which won a design competition in 2009 and also will never exist.)

Also: it seems to no longer appear on Foster + Partners’ website. So there’s that then. (Though they still list Russia Tower! Which was canceled in 2009. And was a very good building.)

Why it doesn’t work: Because nobody wants a giant Christmas wart exploding near the airport. Also, capitalism.

Dongtan

“The eco-city of Dongtan, construction of which is planned for the island of Chongming off Shanghai, is an ambitious vision of sustainable design and urban planning, including an entirely self-sufficient energy system,” sounds great. Current status: disaster. “The island’s western end, where Dongtan was planned, will soon be taken over by high-rise, high-footprint apartments. The first are already under construction.”

Why it doesn’t work: Capitalism, but in the opposite way.

The Lady Landfill Skyscraper

Haha, yes, a floating magical city that cleans the oceans. See you there soon, really soon.

Why it doesn’t work: Seasickness.

Foxconn City

“Apple had redesigned the iPhone’s screen at the last minute, forcing an assembly line overhaul. New screens began arriving at the plant near midnight. A foreman immediately roused 8,000 workers inside the company’s dormitories, according to the executive. Each employee was given a biscuit and a cup of tea, guided to a workstation and within half an hour started a 12-hour shift fitting glass screens into beveled frames. Within 96 hours, the plant was producing over 10,000 iPhones a day.”

Why it doesn’t work: Oh, it does.

That Restaurant Looks Familiar

Why do all the New York Chinese restaurants you see in movies look the same?

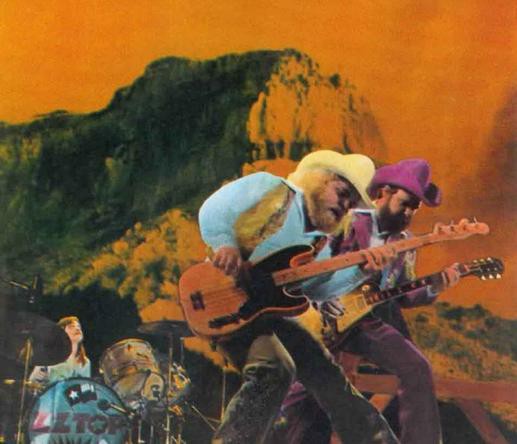

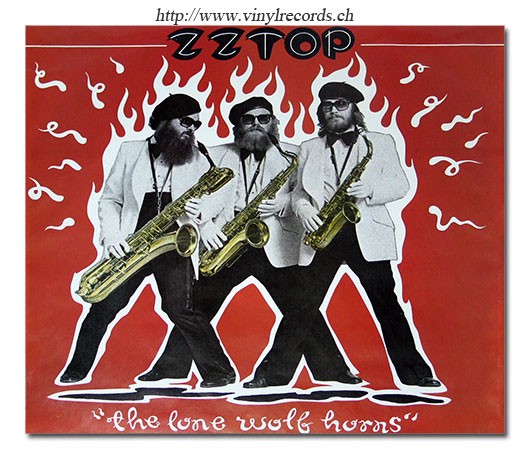

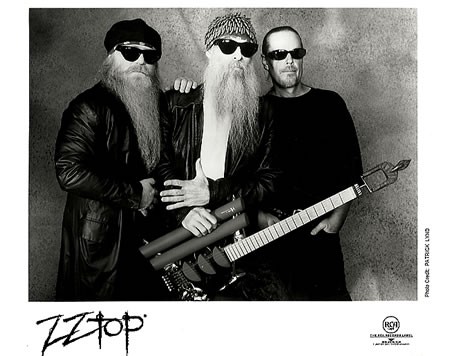

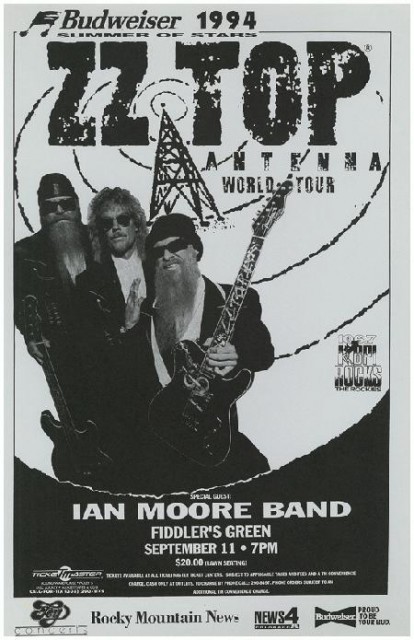

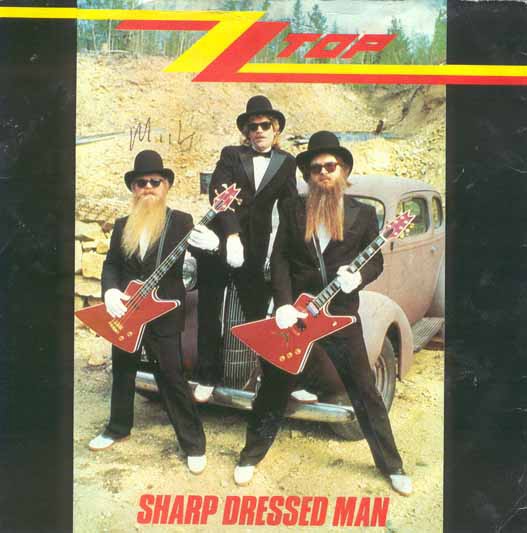

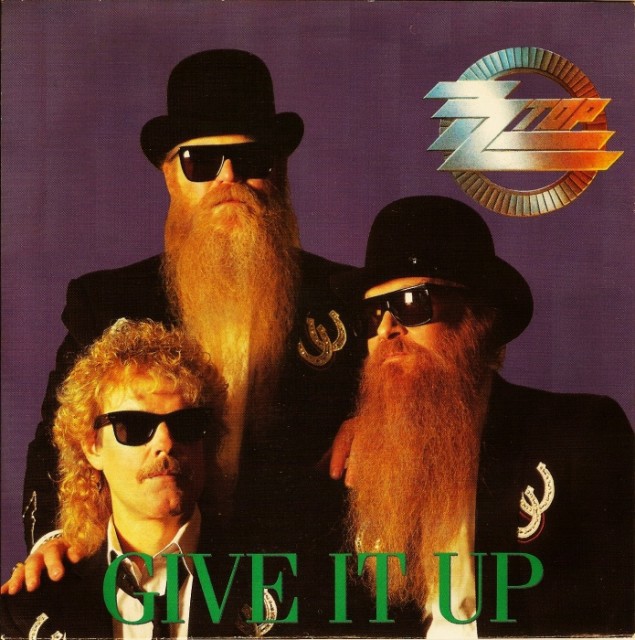

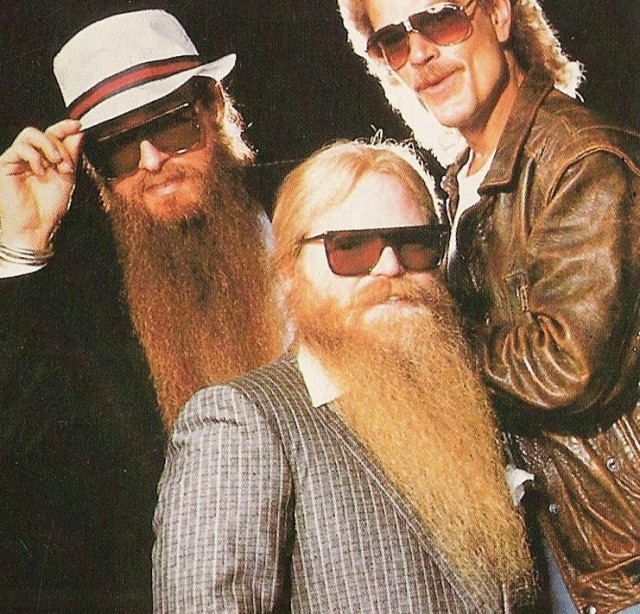

The 15 ZZ Top Albums Ranked in Order of the Band's Total Facial Hair

by Joe MacLeod and Dave Bry

15) Z.Z. Top’s First Album, 1971

14) Tres Hombres, 1973

13) Rio Grande Mud, 1972

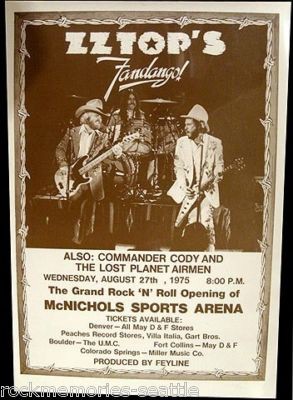

12) Fandango, 1975

11) Tejas, 1976

10) Deguello, 1979

9) El Loco, 1981

8) XXX, 1999

7) Antenna, 1994

6) Eliminator, 1983

5) Recycler, 1990

4) La Futura, 2012

3) Mescalero, 2003

2) Afterburner, 1985

1) Rythmeen, 1996

Goodbye, Anecdotes! The Age Of Big Data Demands Real Criticism

by Trevor Butterworth

If you think of all the information encoded in the universe from your genome to the furthest star, from the information that’s already there, codified or un-codified, to the information pregnant in every interaction, “big” has become the measure of data. And our capacity to produce and collect Big Data in the digital age is very big indeed. Every day, we produce 2.5 exabytes of information, the analysis of which will, supposedly, make us healthier, wiser, and above all, wealthier — although it’s all a bit fuzzy as to what, exactly, we’re supposed to do with 2.5 exabytes of data — or how we’re supposed to do whatever it is that we’re supposed to do with it, given that Big Data requires a lot more than a shiny MacBook Pro to run any kind of analysis. “Start small,” is the paradoxical advice from Bill Franks, author of Taming the Big Data Tidal Wave.

If you are a company that makes sense; but if Big Data is the new big thing, can it answer any big questions about the way we live? Can it produce big insights? Will it begat Big Liberty, Big Equality or Big Fraternity — Big Happiness? Are we on the cusp of aggregating utilitarianism into new tyrannies of scale? Is there a threshold where Big Pushpin is incontrovertibly better than small poetry, because the numbers are so big, they leave interpretation behind and acquire their own agency, as the digital age’s answer to Friedrich Nietzsche — Chris Anderson — suggested in his “Twilight of the Idols” Big Data manifesto from four years ago. These are critical — one might say, “Big Critical — questions. Is Lena Dunham the voice of her generation as every news story about her HBO show “Girls” seems to stipulate or is this just a statistical artifact within an aggregated narrative about women that’s even harder to swallow?

But because we are all disciples of enumeration, the first question is how big is Big? Well, an exabyte is a very big number indeed: one quintillion bytes — which is not as big as the exotically large quantities at the highest reaches of number crunching, numbers which begin to exhaust meaningful language like yottabytes;* but it’s getting there. If you were to count from one to a quintillion, and took a second to visualize each number (audibly counting would take a lot longer), your journey would last 31.7 billion years, and you’d still be less than halfway through a day in the digital life of the world. Or, imagine if each byte occupied a millimeter of visual space: every four days our modern Bayeux tapestry would cover a light year. By way of contrast, Claude E. Shannon — the “father of information theory” — estimated the size of the Library of Congress in 1949 at 12,500 mega bytes, which is by today’s standards, a mere Post-it note of information in the virtual annals of human data, albeit a rather useful one.

This latter historical tidbit (tidbyte?) comes from a thrilling, vertiginous essay by Martin Hilbert — “How much information is there in the ‘information society?’” — that appeared in the August 2012 edition of Significance, the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, (one of the indispensable publications of the digital age). Hilbert has lots of interesting data and, a fortiori, lots of interesting things to say; but one of his most interesting observations is that the big bang of digital data resulted in a massive expansion of text within the universe, and not as you might have intuited, light years worth of YouTube videos, BitTorrent copyright violations, cat pictures and porn:

In the early 1990s, video represented more than 80% of the world’s information stock (mainly stored in analogue VHS cassettes) and audio almost 15% (on audio cassettes and vinyl records). By 2007, the share of video in the world’s storage devices had decreased to 60% and the share of audio to merely 5%, while text increased from less than 1% to a staggering 20% (boosted by the vast amounts of alphanumerical content on internet servers, hard disks and databases.) The multimedia age actually turns out to be an alphanumeric text age, which is good news if you want to make life easy for search engines.

The bathos is forgivable — after all, what else do we spend a vast amount of our time doing other than searching on the Internet for information? But, happily, such “good news” amounts to more than better functionality, a “gosh, how convenient!” instrumental break in the pursuit of better instrumentalism; it also means we can ask bigger questions of Big Data. We can ask what the big picture actually means, and — no less important — we can criticize those who claim to know. We can, in other words, be “Big Critics”; we can do “Big Crit.”

***

Big Crit got a big break in 2012, after a group of researchers at Bristol University’s Intelligent Systems Laboratory teamed up with a couple of professors from Cardiff University’s School of Journalism, Media and Cultural studies. They began with a straightforward, but non-trivial question: how much gender bias is there in the news media — as suggested by the gender ratios of men to women as sources in stories? The key to understanding why the path to answering this question is as important as the answer itself lies in asking, how much information and of what kind would you need to conclude that yes, the media is biased or not?

Pre-Big Crit, you might have had pundits setting the air on fire with a mixture of anecdote and data; or a thoughtful article in The Atlantic or The Economist or Slate, reflecting a mixture of anecdote, academic observation and maybe a survey or two; or, if you were lucky, a content analysis of the media which looked for gender bias in several hundred or even several thousand news stories, and took a lot of time, effort, and money to undertake, and which — providing its methodology is good and its sample representative — might be able to give us a best possible answer within the bounds of human effort and timeliness.

The Bristol-Cardiff team, on the other hand, looked at 2,490,429 stories from 498 English language publications over 10 months in 2010. Not literally looked at — that would have taken them, cumulatively, 9.47 years, assuming they could have read and calculated the gender ratios for each story in just two minutes; instead, after ten months assembling the database, answering this question took about two hours. And yes, the media is testosterone fueled, with men dominating as subjects and sources in practically every topic analyzed from sports to science, politics to even reports about the weather. The closest women get to an equal narrative footing with men is — surprise — fashion. Closest. The malestream media couldn’t even grant women tokenistic majority status in fashion reporting. If HBO were to do a sitcom about the voices of this generation that reflected just who had the power to speak, it would, after aggregation, be called “Boys.”

The closest women get to an equal narrative footing with men is — surprise — fashion. Closest.

But leaving that rather dismal quantitation aside, look at the study’s parameters. This kind of analysis doesn’t just end arguments it buries them and salts the earth — unless you are prepared to raise the stakes with your own Big Data-mining operation. Either way, we’ve dispensed with what you or I think of the media — and the fact that everyone who consumes media gets to be a “media critic” — and empowered a kind of evidence-based discussion. Think about all the pointlessness that can be taken out of arguments about political bias in the media if you can, in real time, dissect and aggregate all the media coverage at any given moment on any question. In the possibility of providing big answers, Big Crit frees us to move the argument forward. If the data is so decisive on gender bias, we now have a rational obligation to ask why is that the case and what might be done about it.

This is why — as interesting as their finding on gender bias is — the key point of the recently published Bristol-Cardiff study, “Research Methods in the Age of Digital Journalism” (pdf) is the methodology. “They programmed a computer to ask simple questions of a vast amount of material and it came up with the same results as human coders would have, “ says Robert Lichter, Professor of Communications at George Mason University in Virginia, and a pioneer in media content analysis (and for whom I worked on several content analyses). “This is a huge breakthrough, and one we’ve all been waiting for because nobody could capture digital media with hand coding.” In terms of seeing the big picture in the exponentially expanding digital mediaverse, it’s like being able to go from Galileo’s telescope to the Hubble. We didn’t have a way of seeing the contents of the whole media system, says the lead author of the study, Nello Cristianni, Professor of Artificial Intelligence at Bristol University, because its vastness meant it could only be seen by automated methods. Now, we have the technology.

***

Being able to see the media mediate in real time is a pretty big development in the annals of Big Data, yet surprisingly, or unsurprisingly, the media didn’t quite grasp why this was a big story. Such coverage as there was — Wired UK — focused on the surface of the study, what it found but not how it found it. Only Gigaom’s Derrick Harris seemed to understand the implications of the analytical breakthrough: “The experiment’s techniques actually point to a future where researchers are spared the grunt work of poring through thousands of pages of news or watching hundreds of hours of programming, and can actually focus their energy of explaining.”

In the not-so-distant past, when nations were kept informed by a handful of news organizations, figuring out how “the media” framed issues for public consumption was a laborious task for political scientists. Teams of trained coders would spend months — in some cases, years — going line-by-line through hundreds of stories and transcripts to draw out the patterns and calculate, using statistical software, what it all might have added up to. As a one-time content analysis serf in this hugely tedious process, explaining that I assigned hundreds of different codes to the different kinds of information embedded sentence-by-sentence in a news story seemed to invite both mockery and pity. It seemed counter intuitive that turning words into numbers could tell us anything really meaningful about the role of the media, how it shaped society, or even what a story really said.

Yet the results of simple, pre-Big Data aggregation were often eye opening. Who knew, for example, that military force was advocated ten times as often as diplomacy in television coverage of foreign news by the US media after 9/11 — and even after the ostensible defeat of the Taliban? Who knew that the US was urged to act unilaterally three times as often as with its allies? And were these trivial findings when set against public opinion surveys which showed that people who got their news from TV were more likely to support the War on Terror, or believe that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction? Unfortunately, we only saw these patterns after they had happened.

Perhaps one of the most startling and effective deployments of content analysis in recent years came through the research of Elvin Lim, and were published in his 2008 book, The Anti-Intellectual Presidency. Lim, now a political scientist at Wesleyan University, analyzed the content and complexity of annual presidential addresses and inaugural speeches to show how political rhetoric had devolved since the 18th century beyond the kind of simplification and clarity one might expect as speech — and society — evolved.

By marrying computational to historical and political analysis (Lim, for instance, interviewed every living presidential speechwriter to elucidate and give context to his data), he showed that at a certain point simplification began to have an effect on the substantive content of political speech, so that (to somewhat oversimplify his findings) FDR was not simply a better rhetorician than say, Bill Clinton, or both Bushes, he was more substantive, in part, because he used language in a more stylistically complex way, and believed that presidential speech should be pedagogical. What happened over the last 50 years, said Lim, was that presidents and speechwriters deliberately abandoned oratory and embraced an anti-intellectual style. The result is demagoguery. It’s an utterly fascinating, compelling, book that absolves neither party from their sins against language. And it’s jammed with data.

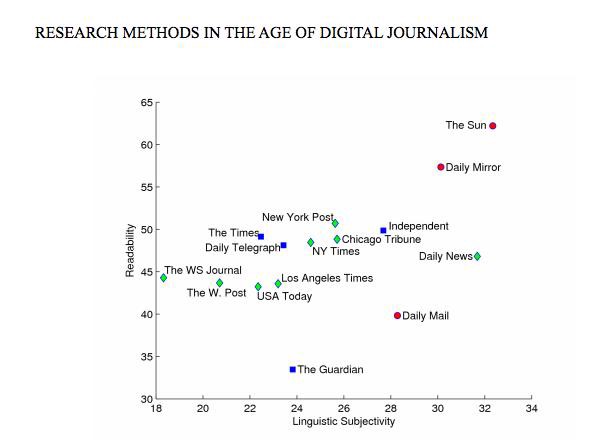

Though Cristianini and his team didn’t deploy the level of analysis Lim did to presidential speech, they did a general test for news media readability using Flesch scores, which assess the complexity of writing based on the length of words and sentences. Shorter, on this account, means simpler, although that doesn’t mean that shortness of prose breadth always denotes simplicity; for general purposes, Flesch scores tend to hit the mark: writing specifically aimed at children tends to have a higher score over, say, scholarship in the humanities, and these differences in readability tend to reflect differences in substantive content.

According to Cristianini et al.’s analysis of a subset of the media — eight leading newspapers from the US and seven from the UK; a total of 218,302 stories — The Guardian is considerably more complex a read than any of the other major publications, including The New York Times. Surprisingly, so is the Daily Mail, whose formula of “celebrity ‘X’ is” happy/sad/disheveled/flirty/fat/pregnant/glowing/ and so on apparently belies its complexity (when I mentioned this to a friend who is an intellectual historian and Guardian reader, she said, “actually, sometimes I do read the Mail”). Together, according to Comscore, these three publications are the most read news sources in the world.

Comparison of a selection of US and UK outlets based on their writing style.

From the study Research Methods In The Age Of Digital Journalism (used with permission).

Cristianini et al. also measured the percentage of adjectives expressing judgments, such as “terrible” and “wonderful” in order to assess the publication’s degree of linguistic subjectivity. Not surprisingly, tabloid newspapers tended to be more subjective, while the Wall Street Journal, perhaps owing to its focus on business and finance, was the most linguistically objective. Despite The Guardian and the Daily Mail’s seemingly complex prose, the researchers found that, in general, readability and subjectivity tended to go hand-in-hand when they combined the most popular stories with writing styles. “While we cannot be sure about the causal factors at work here,” they write, “our findings suggest the possibility, at least, that the language of hard news and dry factual reporting is as much as a deterrent to readers and viewers as the content.” When political reporting was ‘Flesched’ out, so to speak, it was the most complex genre of news to read, and one of the least subjective.

When I asked Lim what he thought of the study via email, this, he said, was the pattern that stood out. “This means that at least in terms of the items included in the dataset, the media is opinionated and subjective at the same time that it is rendering these judgments in simplistic, unsubtle terms. This is not an encouraging pattern in journalistic conventions, especially given that the public appears to endorse it (given the correlation between the popularity of a story, its readability, and subjectivity).”

Even more provocative, when Cristianini et al. looked at the market demographics for the UK publications, they found “no significant correlation between writing style and topics, or between topics and demographics in respect to outlets. Thus, it appears, audiences relate more to writing style than to choice of topic — an interesting finding since prevailing assumptions tend to assume readers respond to both.”

“This means that at least in terms of the items included in the dataset, the media is opinionated and subjective at the same time that it is rendering these judgments in simplistic, unsubtle terms.”

That all this data mining points to the importance of style is just one of the delightful ways that Big Crit can challenge our assumptions about the way markets and consumers and the world works. Of course, we are still, in analytical terms, learning to scrawl. As Colleen Cotter — perhaps the only person to have switched from journalism to linguistics and to then have produced a deep linguistic study of the language of news — cautions, we need to be careful about reading too much into “readability.”

“If ‘readability,’ is just a quantitative measure, like length of words or structure of sentences (ones without clauses),” she says via email, “then it’s a somewhat artificial way of ‘counting.’ It doesn’t take into account familiarity, or native or intuitive or colloquial understandings of words, phrases, and narrative structures (like news stories or recipes or shopping lists or country-western lyrics).” Nor do readability formulas take into account “the specialist or local audience,” says Cotter, who is a Reader in Media Linguistics at Queen Mary University in London. “I remember wondering why we had to have bridge scores published in the Redding, CA, paper, or why we had to call grieving family members, and the managing editor’s claims that people expect that.”

There are other limits to algorithmic content analysis too, as Lichter notes. “A content analysis of Animal Farm can tell you what Animal Farm says about animals,” he says. “But it can’t tell you what it says about Stalinism.”

And that’s why we are still going to need to be smart about how we use Big Crit to interrogate Big Data: a computer cannot discern by itself whether the phrase “Kim Jong-Un is the sexiest man alive,” is satire or a revealing statement of cultural preferences. Problems like this scale up through bigger and bigger datasets: we are on the path to solving problems that can only be seen when a million data points bloom, while, simultaneously, confronting statistical anomalies that rise, seductively, like Himalayas of beans, from asking too many data points too many questions.

But the possibility of Big Crit restores some balance to the universe; we are not simply objects of surveillance, or particles moving in a digital Big Bang, we have the tools to look back, and see where we are at any given moment amid exabytes of data. Changing starts with seeing — and it starts with being able to see how shaping the world as it is being shaped in a deluge of information. But it’s hard not to think that there isn’t more to all this than just media criticism about the news. Take an imminent development, the end of the common page view as a worthwhile measure of human engagement with online media. The data produced by you reading this page will soon evolve into a genome of your online self, which will be followed and analyzed as you flit from screen to screen, and used to predict your behavior and, of course, sell products.

The hidden meta-narratives starring the virtual you don’t just demand criticism because they involve new forms of hidden power (and because all power is encoded with assumptions about what philosophers call “the good”), they renew criticism by revitalizing the notion of critical authority. We can, in fact, say very definite things about the textual and numerical nature of the digiverse because we’ve stepped back into modernity through a new kind of technological flourishing; and, as with our previous adventures in modernism, it’s a place where the critic is indispensable.

* Dear mathematics, please get around to coining “alottabytes;” you know you want to and it would make everybody chuckle when they wrote it. It would also make up for missing the opportunity to enumerate a “gazillion.”

Trevor Butterworth is a contributor to Newsweek and editor-at-large for STATS.org. Image by winui, via Shutterstock.

Where Is This "Mali" Where Frenchmen Are Having Wars?

Lately there has been a lot of confusing stuff in the news about “Mali,” and also “France having a war.” What is going on? Didn’t France lose the war in North Africa, maybe in the 1950s? Also, Vietnam, remember that whole deleted scene from Apocalypse Now, the way the French colonials ate their food, while Vietnamese were getting killed by Robert Duvall? Is he French? And where is this Mali, anyway?

We don’t want you to have to go around feeling like an idiot all the time, so here’s the information you need to deal with any offhand references to “the French war in Mali,” in case you know somebody who works on the copy desk of the New York Times or something: Mali is a landlocked country in West Africa. There have been many coups there. (Coup is even a French word, so you could say, “They had it coming!”) The ancient city of Timbuktu is in Mali, and it was once ruled by the Tuareg, which is now a brand of Volkswagen SUV. Mali is arid in the north and less so in the south. In conclusion, Mali is a land of contrasts.

Up Next In Scandinavian Crime Fiction

“A cleaning lady stole a train and drove it off the end of the tracks and smashed into a house in Sweden on Tuesday, injuring only herself in an incident police are investigating.”

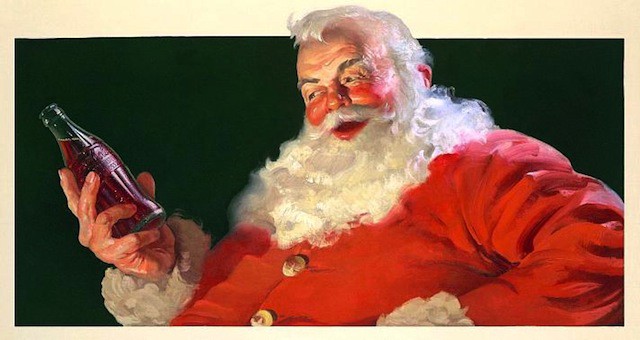

New Coca-Cola Ads Wondering How You All Got So Fat

Here is a disgusting fact you probably don’t think enough about, unless you’re Michael Bloomberg resting between other public tragedies such as climate change and the slaughter of children: The primary source of calories for Americans is “caloric beverages.” Meaning, on top of all the repulsive processed food and industrial fat-meat Americans eat around the clock, corn-syrup drinks provide the largest percentage of calories per American.

Coca-Cola, which adds corn syrup to water at factories around the world, is finally spending your money to buy commercials on the cable-news channels to tell you about this problem.

“Today, we’d like people to come together on something that concerns all of us: obesity,” says a soothing female voice over images of smiling Americans and Coca-Cola products. “The long-term health of our families and the country is at stake.”

Coca-Cola executives announced that as of tomorrow, all sweetened fizzy drinks will be voluntarily recalled and never again manufactured, while “hydration stations” featuring cool, clear water from local sources will be made available at all public and private schools, hospitals and farmers markets thanks to a $7.3 billion endowment from the soda giant. Just kidding, ha ha, the commercial on cable-news channels watched by people in their 70s, that’s the whole anti-obesity campaign.

Is Milan the Most Photogenic City in the World?

by Awl Sponsors

The American photographer Paul Caponigro famously said, “It’s one thing to make a picture of what a person looks like, it’s another thing to make a portrait of who they are.” The same can be said of cities. After all, cities — like people — contain their own identities, histories and secrets. And a good photo captures the essence of a place beyond mere appearances.

As part of an ongoing experiment to unlock the potential of the digital medium in photography, Samsung gave the new GALAXY Camera to 32 photographers to prove that their city is the most photogenic in the world.

Meet Giacomo Por from Milan. Giacomo seeks to capture the spirit of Milan in his portraits, revealing the honesty and reality of life through the composition of light and dark. In this segment, he explores the visual duality of Milan through silhouettes.

You can vote for your city here. Follow Giacomo on Instagram: @saturninofarandola