Something About 'Two Broke Girls' Finally Funny

“Rep. Raul Labrador (R-Idaho) has fired his longtime spokesman over a tweet the spokesman accidentally sent from the congressman’s Twitter account praising a Super Bowl commercial featuring the stars of the CBS show ‘Broke Girls’ provocatively pole dancing, according to the Idaho Statesman. Spokesman Phil Hardy deleted the tweet, which read ‘Me likey Broke Girls’ after 14 seconds, but Labrador’s district director told the Idaho newspaper that Labrador fired Hardy late Monday over the incident. “

Donald Byrd, 1932-2013

The great Detroit-born trumpeter Donald Byrd died Monday in Delaware, where he was artist in residence at Delaware State University. Starting in the 1950s as a member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers before leading his own band for Blue Note Records, he recorded over 50 albums — ranging in style from hard-bop to afro-pop to the experimental hip-hop/jazz fusion he helped Gangstarr MC Guru pioneer on the Jazzmatazz albums in the early ’90s. He was 80.

Writer Asking For Trouble

“People who do not belong to certain groups are asked to defer in their use of certain words to those who do (the practice is known in some quarters as ‘privilege-checking’). Words and phrases are ring-fenced in order to strip them of their ‘stereotypical’ and ‘clichéd’ implications. Recently the use of such terms as ‘mental’ or ‘Brazilian transsexuals’ was said to feed into a stereotype. Of course it does: language is a work in progress and an accumulation of conscious and unconscious usage. It’s not surprising that metaphors and analogies tend towards stereotypes; clichés are ways of using language that have proved useful over time. The words we use every day have developed their various meanings over centuries, and often by making leaps as well as obvious connections. The best writers play with and use stereotypes and clichés to renew thought, not to shut it down.”

San Francisco's Baffling Jejune Institute Gets A Documentary

The toughest part of writing about San Francisco’s Jejune Institute “thing” was trying to describe it, something I attempted to do for this site twice. In a first piece about the citywide game, which was put on by a group called Nonchalance, I went with “[p]art public-art installation, part scavenger hunt, part multimedia experiment, part narrative story.” For the follow-up, I added “underground alternate reality game” to the mix. Both summaries missed the mark, partly because of my own inadequacies as a writer, but also a symptom of the project’s sprawling originality — it wasn’t like anything else out there, and that was part of what made it so fantastic. Thankfully, Spencer McCall went ahead and made The Institute, a 90-minute documentary about the project that neatly encapsulates what made this whole whatever-it-was so wonderful.

It premiered last October at the Mill Valley Film Festival, and has been doing the circuit ever since. It showed at Sundance’s hipper little brother Slamdance this January; highlighting the film in his column, Scott Foundas at L.A. Weekly perfectly summed up my feelings about the whole endeavor by admitting that “[r]arely have I felt so absorbed by a movie about people I found so incredibly annoying.”

Last week, I sat down with McCall in an eerily empty mall food court in San Francisco to chat about making the film. A bit of background about how the game started: Creepy cult-like signs scattered throughout SF urged unsuspecting people to head to the skyscraper located at 580 California in the city’s Financial District. From there, you’d head to the 16th floor and ask the receptionist for “the Jejune Institute.” He or she would hand you a key with some instructions printed on it, and down the rabbit hole you’d go.

Rick Paulas: What was your experience with the game before making the film. Were you a player first?

Spencer McCall: No, I wasn’t. I went to the cusp. I checked out 580 California. You know, word of mouth was going around, everybody was saying, “You got to go to 580 California. I can’t tell you what’s there, you just have to go.”

So me and my girlfriend went, did the whole experience in the Financial District building, went into the Induction Room, got the cards, and walked out onto the streets and were like, this is weird. This is just too weird. They’re probably following us right now. What is this? What is this? So we left. We didn’t even do it. And I put it out of my head for a little bit, but it was still there, like, what is this?

Yeah, just what is this thing trying to sell?

Right. I started to browse online to find out what this organization was, and started seeing terms like “alternate reality game” that didn’t mean anything to me. The biggest question to me was, why doesn’t this cost money? What is it marketing? What is it advertising? And no one knew. Absolutely no one knew where the money came from, or what the point of it was.

A little while later, a friend of mine named Gordo was approached by the Jejune people to lead this kind of street protest for them. They met him on the street and asked him to lead a protest, and he just lead this protest through San Francisco without really knowing what it was about. [Gordo’s story is in the film.] A bit after that, I got laid off from my job and was looking for work, and Gordo said these Jejune people might be looking for someone. So I met them, and they wanted to know my story, what I was about, what I was into, and they said we have a couple of promotional videos we need but we can’t tell you how they’ll be used. You just have to sign this NDA and do them. And they paid almost nothing. So that was kind of how I got behind the curtain a bit.

What were the videos?

Some were commercials for the whole experience, a couple were in-game videos like these quasi-false histories of this organization like where these people came from. And after The Seminar [the game’s closing Act/ceremonies], they left me with this hard drive that had about 700 hours of footage on it. Just everyone’s footage. Handheld, archive, security-cam footage of people entering the Induction Room. They hid a lot of cameras. A lot of photos. I was still unemployed at the time, didn’t have too much to do, so I just emailed Jeff and asked, “Do you mind if I start putting something together?” And he said, knock yourself out. Nine months later, I came back to Jeff with a cut.

I did the first two Acts as a player, but then my reporter instincts got the best of me and I started to interview Jeff and company. Which was great, but I was never able to enjoy the game after that point. And watching Act Four take place, I was kind of jealous of the people playing it.

I was too, a little, but not until I had gotten the whole picture of the experience. I’m not going to say they were crazy, but the players were going down this rabbit hole with no idea where it was going to lead. I’d say I’m more skeptical than that. But then, as I learned more about what this project was, and that the whole point of it was letting go of your skepticism, and releasing yourself from the confines of what’s real and what’s not, you could say I was sort of envious.

When is this going to get released?

We have interest right now. We’ve got distribution offers for iTunes, Netflix, online kind of stuff. We have one for theatrical. We don’t want to be cocky or exclusive or anything, we just don’t want to put it online and have it get buried. There’s like a million things on Netflix.

When you say “we,” does that mean [Jejune creator] Jeff Hull is involved?

I use the Royal We to kind of not sound pretentious. Jeff isn’t really involved, and that’s actually more by his design. He doesn’t want it to come off as it being a vanity piece. And I couldn’t agree more. Jeff likes the movie. It takes a couple little jabs at him, but he likes it. So, I guess when I’m saying “we,” I am generally just referring to myself. Doing a Gollum thing there.

When I was writing my articles, I found it pretty difficult to describe this multi-media super-sensory world with just words. So for you, using video, what was the process of telling this story that was hitting you in so many non-video ways?

That’s the thing. It was a story being told through multiple platforms, which was really cool to me. The fact that you could tell a story not just through TV and not just through a book, but all these interactive immersive elements coming together to give you a story. So, in that regard, turning it into a movie is almost sacrilege. That’s killing the experience. But obviously a big part of the experience was confusion and uncertainty and nuance in reality, so I wanted that to be in the movie too.

But, you know, I really just let the players tell their side of it. A lot of times, they were so deep in it they had a very esoteric perspective. It was very much “well, the Hollow Heads knew that Kelvin has intercepted the blah-blah-blah” and I had to keep going back and saying, “Wait, I don’t know what that means. Can you explain that?” So I kept on approaching the movie like I was showing it to somebody’s grandma. Is she going to get this?

When looking back through the Acts, they progress from being a unique but seen-before scavenger hunt thingy in Act One and Act Two, and then Act Four turned into this magical experience…

Act Four is very much like, this is very beautiful, this all feels so warm. But when you do that in a story it needs to be preceded and followed by adventure. It was preceded by it, but when people didn’t get that out of Act Five that was out of a sense of narrative expectations, in a way that a movie at the end of two-thirds gets really sad and everyone’s all bummed out and then you explode shit and everyone’s happy.

Sure, but that’s the difference between a movie like Die Hard and something like 2001, where you have this open-ended weird symbolic last section. Like, Act Five, I hated it initially. It was just an annoying weekend.

99% of people said that.

But looking back on it, it’s really tough… I certainly don’t hate it anymore. But it’s the argument between meta and straight storytelling, right? You can get the same out of both types. It’s just with straight storytelling you have to take the extra step to see that this means that, and this stands for that. But in meta it’s just, “No stupid, this is what it’s all about. This is what I’m telling you about.”

Did you ever see The NeverEnding Story? What’s cool about that is, the people of Fantasia need a human being to give a new name to the Empress. And the only way they can get someone to come to their world is to create a story that someone can immerse themselves in, they can only come to this world and save it if they believe that the story they’re reading is essential and necessary. The story doesn’t matter. It’s just the tool to get you to come together and open up your eyes. It’s not the Holy Grail; it’s the quest for the Holy Grail. But everything that the Holy Grail would give you, you could gather on the quest. So that was the message. And that’s not necessarily a new message. You know, “it’s the journey not the destination.”

Ultimately, then, the documentary is kind of the final draft of Jeff’s project. No one’s going to play the game again, it’s gone. This is what’s ultimately going to exist. When you were making it, did you feel any obligation to preserve something?

No. Not at all. I wasn’t making this to be the preserver of this ancient world. It was just to answer the basic, fundamental question of what story is this telling. Yeah, there is so much peripheral story crap, and links, and the B-Boys being connected to these delta particle drugs that were made by Eva’s father’s friend who went missing and created the polywater, and whatever. It’s like, no. That’s not… again, the story didn’t matter. I cut where it didn’t make sense to me.

What, ultimately, is your final impression of the game in general and what they did?

Which is actually really interesting is that most of the people who participated were, much like myself and much like people in the Bay in general, very secular people. I’m not a religious person, none of the people who participated in this game were. Which isn’t really surprising. But what a lot of these people got was this sense of spirituality, or a sense of something more going on in their reality. And who cares if that’s created by people instead of a magic thing? These people got this sense of congregation, and they came together. It was no mistake that Act Four was in a theological establishment. So that’s what’s really cool to me, is that you can believe in something more going on. You can believe in magic and you don’t have to attribute it to a God or whatever…

… or a corporation, or a movie…

… but at the same time, people love to say they’re spiritual but not religious, and this was definitely religious but not spiritual. Because it was all the tradition and story that religions have, but none of the necessity to believe in any of the magic. And I don’t know if that was really Jeff’s idea. His idea was to get people to stop looking at their phones, to explore the world they live in, not be afraid to go down an alley because they think it might be owned by someone. You know, don’t go robbing anybody, but explore it. It’s your city, too. That would be Jeff’s thing.

Mine would be just to question the media you’re presented with. I think a movie has the ability to make you open your eyes and linger and bounce around in your brain for awhile, but don’t take it too seriously. And if you do, be sure you really question it and get the answers. It’s like Jaws. If you’d seen the shark in the beginning, would it be that sharp or spooky of a movie? Probably not. You know at the end they do show the shark. I don’t think I ever showed the shark in this movie. But that’s the idea. Go find the shark yourself. You decide.

Previously: Last Chance: The Mysteries Of San Francisco’s Creepy Jejune Institute and The Perplexing Final Chapter Of San Francisco’s Jejune Institute

Rick Paulas is an Institute graduate.

Heaviest Drinkers Cooler Longer

“People who grew up in states where it was legal to drink alcohol before age 21 are more likely to be binge drinkers later in life, according to a new study.”

A Poem By David Biespiel

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

To Wendy from the Crow’s Nest

— Portland

My Dear —

If not from dream, before dawn,

When the rain has not perished over the house,

And you have sworn off four nights of sleep,

And I have wrestled with a mind of airplanes and birth,

And to know that you are leaving again in the morning,

With me staying — or is it the other way around,

Me leaving, and you staying, or both of us

Boarding another flight to a strange city?

— And always, too, both of us wondering

If any of this exists,

sleep, skies, birth,

Mumbling in the frontiers of hotel rooms,

Hauling our slender passports.

Plus: Speaking in forgotten tongues

Made up from the peasant poems of the Jews

And the soft-feathered hymns of the Cherokee.

And you so happy when we strolled through

The Dixie Classic Fair that autumn day

in Forsyth County, North Carolina,

Because the caramel apples were made by hand

And the tender pigs raced so hard

Around the swine track for their cookie,

And the blue ribbon chestnuts and sunflower seeds

Lay in their trays like hearts,

And the ladies from First Baptist

serving fried tomatoes

Whispered to us

That we must avoid the brownies but it’s OK

To eat the sweet potato pie,

And then, all day, not one Carolinian

Stopped us to talk about the trophies of eternity.

But, remember, all of this does exist —

Including the windy Moravian spires

And the dazzling bright Sunday hats,

Including the creeping lawns trimmed out to the roads,

Including the Avenue of the Arts

unzipping after dark

With its four-colored roosters

And fried chicken on Trade Street

And secret marriages

And the bronze whiskey at Finnegan’s Pub

Brought over by svelte girls with shaved heads —

And the two of us exhausted with drink

and, finally, quiet,

So quiet, as if we could hear clarity

Bobble up from the bottom of the earth, so quiet,

Lushly quiet, leaf-by-murmuring-leaf quiet,

And now home,

Home in our own room, a nest

Above the garden’s light, and waking.

David Biespiel is the author of four collections of poetry, most recently The Book of Men and Women. His next book, Charming Gardeners, is due out later this year.

There’s nothing like a poetry party, ’cause a poetry party don’t full stop. Get your poetry party on here, in the archives of The Poetry Section. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Fit Of Pique

If you are previewing something or getting an early glimpse, you are taking a PEEK. If you’re at the summit of the mountain, you’re at the PEAK. Please make a note of it.

Your Massively Open Offline College Is Broken

by Clay Shirky

I wrote a thing last fall about massive open online courses (MOOCs, in the parlance), and the challenge that free or cheap online classes pose to business as usual in higher ed. In that piece, I compared the people running colleges today to music industry executives in the age of Napster. (This was not a flattering comparison.) Aaron Bady, a cultural critic and doctoral candidate at Berkeley, objected. I replied to Bady, one thing led to another, the slippery slope was slupped, and Maria Bustillos ended up refereeing the whole thing here on The Awl.

Bustillos sees institutions like San Jose State experimenting with credit for online courses from startups like Udacity, and asks: “are we willing to jeopardize the education of young people (at the cost of millions or billions in public funds) on a bet like that?”

To which my reply is: “Depends. How well do you think things are going now?”

Bustillos’ answers seem to be that in the world of higher education, things are going fine, mostly, and that the parts that aren’t going fine can largely be fixed with tax dollars. (Because if there’s one group you’d pin your hopes for an American renaissance on, it would be state legislators.) I have a different answer: School is broken and everyone knows it.

That sentiment is the first sentence of Kio Stark’s forthcoming book, Don’t Go Back to School. It’s a guide for people taking the advice in the title; Stark interviewed almost hundred people who dropped out or took a pass on everything from high school to grad school, but still figured out how to learn what they needed to learn, in order to do what they wanted to do.

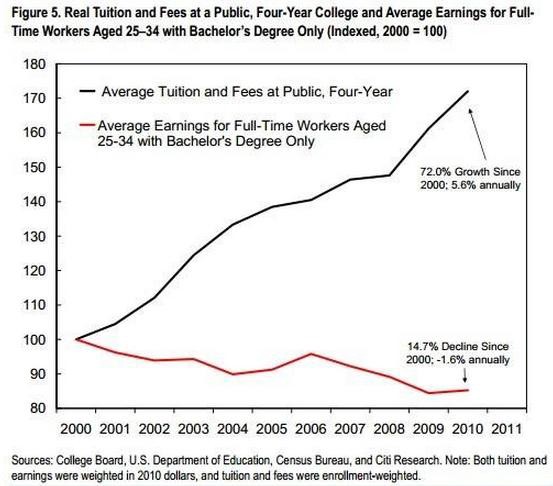

If you want to see what’s driving the imperative to learn without paying for a traditional education, take a look at this chart, originally from a Citi report.

Forget private school. Tuition and fees at public four-year colleges went up 72% last decade, even as the market value of a bachelor’s degree fell by 15%.

The value of that degree remains high in relative terms, but only because people with bachelor’s degrees have seen their incomes shrink less over the last few years than people who don’t have them. “Give us tens of thousands of dollars and years of your life so you can suffer less than your peers” isn’t much of a proposition. More like a ransom note, really.

This is the background to the entire conversation around higher education: Things that can’t last don’t. This is why MOOCs matter. Not because distance learning is some big new thing or because online lectures are a solution to all our problems, but because they’ve come along at a time when students and parents are willing to ask themselves, “Isn’t there some other way to do this?”

MOOCs are a lightning strike on a rotten tree. Most stories have focused on the lightning, on MOOCs as the flashy new thing. I want to talk about the tree.

* * *

In her piece for The Awl, Bustillos asks us to put ourselves in the position of an 18-year-old embarking on an academic career, to which the only sensible response is “No, let’s not do that.” Focusing on the nation’s college-bound 18-year-olds is an almost perfect recipe for misunderstanding higher education in this country.

If you ask Google what a college student looks like (SafeSearch on, please), you get a gaggle of chipper adolescents. And if you ask Google, the collective id of the wired world, what a college campus looks like, you’d conclude that their second biggest expense after salary is fertilizer. These two images — the young person on a journey of self-discovery; the stone building on the verdant lawn — are in the background of most mainstream conversations about college, images that are familiar, comforting, and statistically wrong. Students younger than 23 are now in the minority, and competitive, residential colleges are a minority of the institutions that serve them.

Imagine picking a thousand students at random from among our institutions of higher education. Now imagine unpicking everyone at one of US News’ Top 100 liberal arts colleges or universities. You’d expel anyone from the Ivy League, Stanford, MIT. Anyone from from Emory or Rice. Anyone from Vanderbilt, Clemson, Drexel. Anyone from the famously good state schools — UMass, Virginia, the California universities. After ejecting those students from your group, how many of the original thousand would be left?

About 900.

The total enrollment on those two lists — which includes almost every good college you’ve ever heard of and some you haven’t (Wabash; SUNY College of Forestry) — only accounts for a tenth or so of the 18 million or so students enrolled this year at one of our thousands of institutions of higher education.

If you want to know what college is actually like in this country, forget Swarthmore, with 1500 students. Think Houston Community College, with 63,000. Think rolling admissions. Think commuter school. Think older. Think poorer. Think child-rearing, part-time, night class. Think 50% dropout rates. Think two-year degree. (Except don’t call it that, because most graduates take longer than two years to complete it. If they complete it.)

If you want to know what college is actually like in this country, skip Google Images, and scroll through the (still heartbreaking) We Are The 99 Percent Tumblr, looking for the keywords “student loan.”

* * *

Though educational materials have been online for as long as there’s been an online, and though the term ‘MOOC’ was coined half a decade ago, it was only last year that they stopped being regarded as a curiosity, and started being thought of as a significant alternative to traditional college classes. In the face of this threat, the inheritors of that tradition are making a case for themselves.

In a widely quoted piece from The Chronicle of Higher Education last summer, Daryl Tippens, the Provost of Pepperdine, mounted that defense this way:

We know that effective learning is best achieved through the engagement of other deeply attentive human beings. The learning might occur in a traditional classroom, but it might happen in a different space: a lab, a mountain stream, an international campus, a cafeteria, a residence hall, a basketball court.

No PowerPoint presentation or elegant online lecture can make up for the surprise, the frisson, the spontaneous give-and-take of a spirited, open-ended dialogue with another person.

As MOOCs threaten to encroach on face-to-face learning, institutions like Pepperdine are standing foursquare against the virtualization of the college experience, against weakening the sacred interaction that… hang on, what’s this? Pepperdine offers online degrees? Why yes. Yes it does.

After the Provost had staked his institution’s reputation on the production of IRL frissons and whatnot, you’d think they’d keep this sort of thing to a minimum, but nope. You can get a masters online from Pepperdine. You can get a doctorate. While taking 85% percent of your classes over the internet. (So much for that mountain stream.) But don’t worry, that 15% face-to-face meeting time is strategically scheduled.

Even the spontaneous giving-and-taking among deeply attentive human beings can sometimes take a beating at Pepperdine:

The main disservice to the Humanities series is that instead of conducting classes in standard intimate class settings students are herded into large lecture classes…. The course’s enrollment stands at around 245 students but only about half come on a regular basis. An informative lecture about the bubonic plague is merely background noise to a room full of students on Facebook.

Ah yes, the open-ended dialogue that emerges from cutting your big lecture classes. I remember it well.

Pepperdine is, I want to emphasize, a good school. It’s a great school, in fact. Their religion thing might not be your bag, but if someone you know got into Pepperdine, you’d be happy for them. That’s the key bit: even great schools offer online classes. Even great schools, with low student/teacher ratios, have at least some big, impersonal lectures. There isn’t any pure college left to rally around. (Ok, ok, Deep Springs and St. John’s College. But you know what I mean.)

The platonic versions of college defended by Teppins and his ilk sound idyllic, but they don’t sound like most actually existing colleges. Often, they don’t even sound like the colleges where the defenders themselves work.

* * *

Both Bustillos and Bady are outraged about the threats to higher education, as well they should be, and as am I. The biggest difference between us is that I think the calls are coming from inside the building.

Prior to the internet, the last technology that really reorganized teaching was the microphone. Without a microphone, manageable class size tops out at about 50. With a microphone, the sky’s the limit — you can have huge lectures with expensive profs, and lots of sections taught by cheap TAs and adjuncts. What’s not to like?

The microphone was a way to lower our cost per student, without lowering the price we charged. That pattern is common to many of the changes these last thirty years or so. More internships. More transfer credits. More recognizing credit for work, or “life experience.” More competency-based credits, meaning credit for knowing something, rather than for learning something. And so on.

The end game is degrees that are little more than receipts for work done elsewhere. Empire State, Excelsior, Thomas Edison, all these institutions and more convert a loose set of credits into a diploma, without much of anything resembling a curriculum. A kid named Richard Linder just figured out how to get an Associates Degree by stitching together 60 credits from 8 separate institutions, not one credit of which was earned in a college classroom. (Fully a quarter were from various forms of FEMA certification.) Linder gets an A for moxie, but it doesn’t say much for the institutions nominally policing educational coherence.

This vitiation of the diploma is Goodhart’s Law in action, where a socially useful metric becomes increasingly worthless, because the incentives pushing towards adulteration are larger than those pushing towards purity. This is not some bad thing that was done to us in the academy. We did this to ourselves, under the rubric of ordinary accreditation, at nonprofits and state schools. Yet I’ve never once heard the professors fulminating about MOOCs also suggest shutting down Excelsior College. In the academy, we are terrible at combating threats from the current educational system, but we are terrific at combating threats to it.

The thing to understand about the current conversation is how bad things were, for how many students, long before organizations like University of the People ever launched. In the academy, we’ve been running a grey market in unsupervised internships and larger and larger lectures for a generation already. MOOCs threaten that market.

Bustillos worries that San Jose State and Udacity are charging $150 a course. But what’s the public college alternative? They could be going to California’s UC Online program, where a course costs $1400. The San Jose deal was brokered by Governor Brown in part because he was so disgusted with what his own institutions were up to.

In the academy, we’re fine with anything that lowers the cost of education. We love those kinds of changes. But when someone threatens to lower the price, well, then we start behaving like Teamsters in tweed.

* * *

I’ve been thinking about the effects of the internet for a couple of decades now. I’ve watched industry after industry forced to renegotiate their methods and models, in the face of a medium that allows for perfect copying, global distribution, zero incremental cost, ridiculously easy group-forming: The music business. Newspapers. Travel agents. Publishers. Hotel owners. And while watching, I’ve always wondered what I’d do when my turn came.

And now here it is. And it turns out my job is to tell you not to trust us when we claim that there’s something sacred and irreplaceable about what we academics do. What we do is run institutions whose only rationale — whose only excuse for existing — is to make people smarter.

Sometimes we try to make ourselves smarter. We call that research. Sometimes we try to make our peers smarter. We call that publishing. Sometimes we try to make our students smarter. We call that teaching. And that’s it. That’s all there is. These are important jobs for sure, and they are hard jobs at times, but they’re not magic. And neither are we.

Mostly, we’re doing the best we can. (Though some of us aren’t, as with bottom-feeding scum like Kaplan U and Everest, but those institutions are just asset-stripping student loans.) But our way of doing the best we can is to keep doing what we’ve always done, modifying it a bit with stuff we make up as we go along. Just like most people inside most institutions. Some years that works out fine, but we haven’t had so many of those years recently.

For all our good will, college in the U.S. has gotten worse for nearly everyone who relies on us. For some students — millions of them — the institutions in which they enroll are more reliable producers of debt than education. This has happened on our watch.

The competition from upstart organizations will make things worse for many of us. (I like the experiments we’ve got going at NYU, but I don’t fantasize that we’ll be unscathed.) After two decades of watching, though, I also know that that’s how these changes go. No industry has ever organized an orderly sharing of power with newcomers, no matter how interesting or valuable their ideas are, unless under mortal threat.

Instead, like every threatened profession, I see my peers arguing that we, uniquely, deserve a permanent bulwark against insurgents, that we must be left in charge of our destiny, or society will suffer the consequences. Even the record store clerks tried that argument, back in the day. In the academy, we have a lot of good ideas and a lot of practice at making people smarter, but it’s not obvious that we have the best ideas, and it is obvious that we don’t have all the ideas. For us to behave as if we have — or should have — a monopoly on educating adults is just ridiculous.

Related: Venture Capital’s Massive, Terrible Idea For The Future Of College

Clay Shirky is an Associate Professor at NYU. Photo of UC Berkeley’s Pimentel Hall by Daniel Parks.

"The Kessel Run," a Han Solo Grindhouse Double Feature, and Other Prequels

The Han Solo story would take place in the time period between Revenge of the Sith and the first Star Wars (now known as A New Hope), so although it’s possible Harrison Ford could appear as a framing device, the movie would require a new actor for the lead — one presumably much younger than even the 35-year-old Ford when he appeared in the 1977 original.

- Han Solo (CGI Dustin Hoffman) and Lando Calrissian (CGI Sly Stone) wind up with a bunch of rebels in a woodsy canyon. While imperial forces hassle teen-aged rebels on the nearby Sunset Strip, Han and Lando find themselves in a groovy love triangle with a local folk princess (CGI Joni Mitchell) who might be the emperor’s daughter or just a beguiling nut.

- Han Solo (CGI Charlton Heston) crash lands on a planet filled with terrible ape-men. They lock him in the cowboy jail and do weird experiments on his junk. He is befriended by a gruff but loyal ape-man (CGI Chewbacca), who steals some horses and takes Han to the beach in New York, but now it looks just like Malibu.

- Han Solo (Justin Bieber in Wolverine wig) does a YouTube proving he can sing despite his devil-may-care attitude. Big-time promoter Jabba the Hutt (CGI Bill Graham) offers Solo a contract, but the fine print says Han must also live under Jabba’s torture castle with an enraged monster (Phil Spector via Skype).

- Han Solo (Taylor Kitsch) is hired to take an annoying rebel leader (Taylor Swift) to some other planet in a small plane. The plane crashes, now they live on a primitive island, just bickering and having sex all the time, until it turns out this is the Emperor’s private vacation island.

- Han Solo (Zac Ephron) is placed in a mental institution because he steals so much stuff. Everybody there is a weird alien. The nurse (CGI Nurse Ratched) hates him so much because he is handsome and sexy. Large native hair-monster (CGI Art Garfunkel) befriends Han. Everybody dies but Han, who flies away on the Nurse’s sky-speeder.

- Han Solo (Ellen Page) and his spice-dealing friend Billy (Matt Smith) ride moto-speeders to Mos Eisley just to clear their heads and get away from The Man. They meet a hip young senator (CGI young Christian Slater) and have a nice talk about The Force and then get attacked by the stormtroopers in a Jedi graveyard.

- Han Solo (Ben Whishaw) goes to an Outer Rim diner and gets so much hassle because he only wants toast, no chicken salad. His partner Chewbacca (CGI John Belushi as Joe Cocker) orders four fried chickens and a coke. A pair of annoying lesbians (Kristen Stewart, Dakota Fanning) cause trouble in the spaceship. Class differences are explored.

- Jennifer Lawrence plays all parts, is tour de force.

- Han Solo (Scoot McNairy) is expected to take over the family crime business from his weird old dad (Tom Waits), even though Han is a promising young officer in the Imperial military. But when Jabba the Hutt (CGI Chris Farley) tries to assassinate Han’s “godfather,” there is no choice but to start killing crime lords, guns hidden in the toilet, etc. Everybody thinks of the planet where they used to live.

- Han Solo (Josh Hutcherson) goes to work for the baddest dude in town, Lando (Tyler the Creator), and also has an open marriage with Beyoncé (Beyoncé). The imperial war is just bringing everybody down so much, and they all decide to “drop out” with some other free spirits at Zabriskie Point in the Jundland Wastes. The arrival of a warlord princess (Chloë Grace Moretz) brings bizarre complications.

- Han Solo with a mustache (CGI Burt Reynolds) breaks out of jail with Lando in his Black Panther militant chic phase (“Tracy Jordan”). They meet up with Chewie (Cee-Lo), but he’s always so high that the plan to steal an ATM machine goes awry. Will they reach Los Angeles with the spice before the Greedo biker gang (cast of HBO’s “Girls”)? No, they will have an immense, bloody, 25-minute machine-gun battle in the Mojave Desert. Soundtrack by the country-western lineup of The Byrds.