12 Million Americans Still Unemployed: Things Are Looking Up!

How is 7.7% unemployment considered good news? When it’s a little less than 7.9%, and people with money are ready to find good news wherever they look.

The housing markets are booming, where the rich people live. The stock markets haven’t gone so high since Dick Cheney was in the White House — except for the NASDAQ, which still hasn’t recovered completely from the dot-com bust of 2000, even though the tech companies are doing pretty well and NASDAQ stocks are at a 12-year high. Monthly rents in San Francisco now average $2,700 for a one-bedroom apartment. New car sales are back to pre-recession numbers.

And 12 million working-age Americans who want to work cannot find a job. That’s the population of Los Angeles County plus the population of the city of Los Angeles again. Or nearly double the Bay Area population, or millions more than the entire population of New York City. What a wonderful time to finally start cracking down on entitlements! Austerity is not only the answer to budget problems, but also the answer to amoral laziness. Also let’s stop giving vaccines to poor children, as they will only grow up to be unemployed.

Scientists Still Talking About How Hot It Is As If We Might Actually Do Something About It

“Global temperatures are warmer than at any time in at least 4,000 years, scientists reported Thursday, and over the coming decades are likely to surpass levels not seen on the planet since before the last ice age.”

Phoenix, "Entertainment"

Besides being hugely fun and entertaining to watch, the new video from Phoenix serves to remind us the extent to which the annoying-but-very-catchy tunes of the American power-pop band Fun (insert your own period if you like; I can not do it) are indebted to their French predecessors. Here, those predecessors (Phoenix) are played by Korean actors. Which serves to remind many of us (because we are racist Americans who cannot help but to conflate East Asian countries in our provincial minds) where we first heard Phoenix: in that great Tokyo party scene from Sofia Coppola’s Lost In Translation. Which I watched for the first time in years last weekend and is still so, so, very excellent. (And is now ten years old!!!) Nothing will help me figure out why the word “phoenix” is spelled with the “o” coming before the “e.” I will be misspelling it forever.

Art and Flutes and Fan Mail and Stuff

This weekend in New York City: not the best weekend the City has had to offer this year! Some fun things on the calendar but I would mostly suggest staying home and taking it easy, honestly.

Dear Coot Veal

Sorry for writing you and asking for your autograph under false pretenses.

This was a long time ago. 1981 or 82, I think. My friend Chris Pack and I were ten or eleven years old, and deeply, totally obsessed with baseball. We collected cards, memorized statistics, perfected pantomime of our favorite players’ pitching deliveries and batting stances — Dan Quisenberry’s submarine sidearm, Cecil Cooper’s low-slung crouch, Graig Nettles’ rod-straight right leg. In the summer, we’d watch the Yankees on Channel 11 every night (the Mets on Channel 9 if the Yankees had an off day) and play our own games of Wiffle ball in my backyard — all day, everyday. The fence to our neighbor’s yard, the outfield fence, was covered in honeysuckle vines, and another friend of ours, Blair Bryan, came up with the name “Brigley Field.” (Like Chicago’s famous ivy-draped Wrigley Field, but with a “B” for my family’s name.) We’d get out there early in the morning — us and Blair, or Jamie Mazacco, or Chris’s little brother Jon, or Kirby Reynolds who lived on the next street over — and play until it was dark. Sometimes even later. We’d catch lightning bugs and smush their phosphorescent abdomens all over the ball so we could see it at night. (Gross, right? But it actually worked pretty well.)

Like many nerd baseball fans, we became scholars of the history of the game, poring over our copies of The Baseball Encyclopedia, ranking players, making fantasy line-ups and all-star teams, arguing minutiae for hours. That’s where I learned your name, from the The Baseball Encyclopedia. It lists every player to have every played in a major league game. And you played in 247 of them, over six seasons, from 1958 to 1963, for the Detroit Tigers and the Washington Senators and the Pittsburgh Pirates. You amassed 141 hits, a career batting average of .231 and exactly one home run. (August 11, 1959 — man, that must have been a fun day, huh? Do you still call Billy Pierce, the White Sox pitcher who served it up, every year on that day to razz him? I hope so. He’s 85 now, and you’re 80.) As I’m sure you’re aware, and I hope comfortable talking about, these are not particularly strong batting statistics. You were apparently a defensive specialist. You played shortstop. I miss the days when defensive skills trumped offense skills at the shortstop position. I liked a time when a toothpick of a man like Mark Belanger, with his lifetime average of .227, could be granted four reliably futile at-bats a game for 13 years for a great team like the Baltimore Orioles, simply because he was so very good at scooping up the ground-balls the opposing hitters hit during their turn at the plate. I suppose Belanger’s replacement, the giant and mighty Cal Ripken, had something to do with recasting the standard, but I like to blame Alex Rodriguez. I like to blame Alex Rodriguez for as much as I possibly can. Do you find him as detestable as I do? I would think, probably.

After summer ended, and the baseball season, and the Wiffle ball/lightning-bug hunting season, we found other ways to feed our yen. Chris got this book that compiled big leaguers’ mailing addresses. We wrote letters to all our current favorite players. And many of our historical heroes — Harmon Killebrew, Hank Greenberg, Yogi Berra. We always included a baseball card, or a photograph, cut out of Sports Illustrated or the Sporting News’ preseason preview or something and a self-addressed stamped envelope. We tried to be as polite as possible, and lots of people signed the stuff and sent it back.

But the winter is long for hyperactive pre-teen baseball fans, and after months of mailing numerous letters a day, we eventually ran out of people to write to whose autographs we genuinely wanted. Chuffed as we were to have discovered this great mail-away autograph system, and without much else to do, we started choosing people for reasons of novelty. You have an unusual name. Or at least, by 1980s suburban New Jersey standards, it was unusual. I suppose in the 1930s, in Sandersville, Georgia, where you’re from, a name like Orville Inman Veal, or even a nickname like “Coot,” might not have struck a pair of bored brats as being quite as hilarious as it did Chris and I. Making fun of names that sound different to you is the lamest kind of humor anyway. Remember when David Letterman hosted the Oscars and tried to milk laughs out of the fact that Oprah Winfrey and Uma Thurman were in attendance? “Ooooooprah,” he said, “Uuuuuma…” He’s never bombed so badly in his life. And good thing, too. It’s hegemonic at heart, that vein of humor. Silly, mean-spirited kid-stuff, even for kids. Anyway, I hope not to hurt your feelings by telling you this now. But I sent you that letter as a lark.

I forget exactly what I wrote. Some sarcastic praise about your statistics, your single homerun, kept just dry enough so that you might not catch the irony and would still send me back your autograph. I remember thinking myself very clever. And reading it aloud to Chris and laughing until my stomach hurt.

What goes around, as they say, comes around. Two or three years later, when I was in eighth grade, at a point in my life when I wanted very much to be attractive to girls my age, but was apparently not very attractive to those girls, my friend Jerome Connolly and I started to get these coy, flirty phone calls from two girls who said they were from a neighboring town. We were confused; they said they’d seen us at the mall, or from across the river near my house, and looked up our names in a copy of our school yearbook that they had access to at one of their cousin’s houses or some such nonsense that challenged our suspension of disbelief; but we were not about to hang up. They said they thought we were cute. They said they wanted to meet us. We did our best to play it cool, but I remember giggling like a ninny.

Of course, we never met them, and the calls stopped after a few days. And a month or so later, that summer, after school had ended, two girls from our class, Stephanie Maimone and Lisa Humphries, girls of a higher social status than Jerome and I enjoyed, let us in on the joke they’d played. They told us about it one night at the ice-cream shop near the gazebo by our town’s Borough Hall; they sat down at a table we were sitting at and asked us whether we knew the girls — I forget the names they’d made up. They were their friends, they said at first, one of them was one of their cousins, but they gradually spooled out more and more information so that we’d know that this was a confession. They weren’t monsters; they wanted us to laugh along with them. They weren’t monsters any more than Chris and I were. But, man, the harsh, bright overhead lighting in that ice-cream shop glared down harsher and brighter than it ever had before that night. And as I tried to muster up some laughter to go along with theirs, to prove that I was a good sport and not at all bothered by such silly kid stuff, my stomach hurt — and not from the laughing.

I still have your autograph. It’s on a piece of white-lined paper that I cut into a neat rectangle. (Not having any baseball cards of pictures of you to send.) The lines have faded but your name is clear and legible. I keep it in an old, green ring-binder with all those other autographs — Willie Mays’, Sandy Koufax’s, Ted Williams’, Hank Aaron’s — in a transparent plastic folder made to display baseball cards.

“Best wishes, Dave,” you wrote, “’Coot’ Veal.”

Previously: Dear Sanj

The book Public Apology, a memoir based on the Awl column (but made mostly from new, never-before-published material) comes out March 19th through Grand Central Publishing. (Preorder it here!)

Dave Bry has a lot to apologize for.

New York City, March 6, 2013

★ Less a day than a dull passage of exposition, the dutifully plausible transition from yesterday’s brightness toward tomorrow’s forecast of snow. The jackhammer on an excavator rattled under the heavy sky. Styrofoam peanuts blew off a passing garbage truck in a pale, scattering burst like blossoms from a tree. The wind pushed coattails out and back. Little droplets beaded on a taxi. Sometimes the pavement was dampened; other times it dried out. The only break in the trudge toward something else came at dusk, as the late blue light filled the spaces between the buildings on Broadway, setting off their oblique angles as they receded downtown.

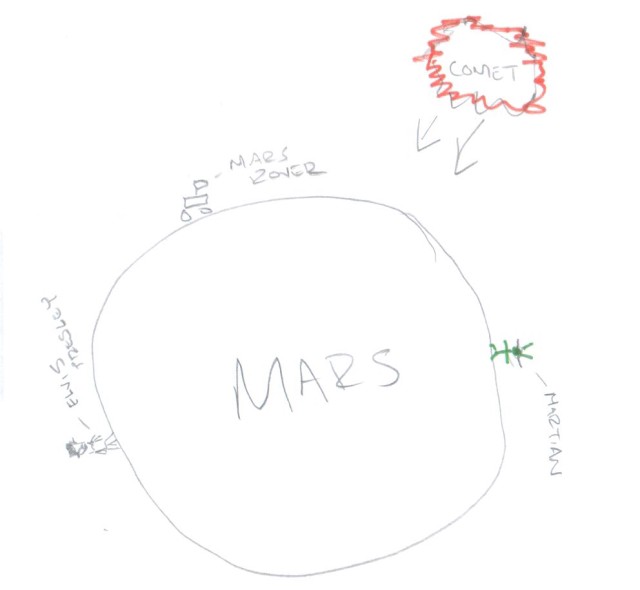

If Mars Had Panicky Idiots, Martian Facebook Would Be Super-Annoying Right Now

“Mars may have a really bad day next year on October 19th. That’s when there is a very slight chance a newly discovered comet may impact our neighboring planet, says NASA…. Based on observations to date the comet nucleus could be a real monster — as big as 9 miles (15 km) to 31 miles (50 km) wide. With it’s velocity clocked at 35 miles (56 km) per second, the energy force of the collision could be measured in the billions of megatons, resulting in a crater hundreds of miles wide. This could be an impact that rivals the one that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago on our planet and would be bright enough to be even seen with the naked eye from Earth.”

Image: NASA

You Won't Believe These Seven Amazing Papal Elections

by Josh Fruhlinger

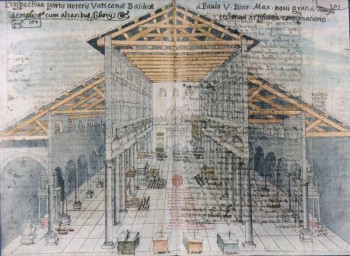

The Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church are gathering, right now, to start the process of electing the next pope. Exciting stuff, eh? No, not really, to be honest! What will almost certainly happen is that this group of old ecclesiastics, all of whom were chosen by one of the last two popes, will be shut up in the mildly cramped but relatively posh digs of the Apostolic Palace, and will take a few days, tops, to come to a consensus on who the next pope will be. Maybe the winner will be a surprise, and maybe the conclave will end on the first vote for once, or will extend out for a week or two. But the era of fun papal elections — and by “fun” we mean elections that were violent, weird, chaotic, overtly corrupt, or that elected more than one pope — is sadly over. We present this list as a public service to memorialize the days when papal transitions were significantly less efficiently managed.

1. Fabianus, 250: The Bird Election

In the early days of Christianity, bishops were elected through a somewhat informal process involving the clergy and parishioners of the diocese. In the mid-third century, Christianity was still illegal in the Roman Empire, and while the Bishop of Rome was considered the most important see in the Western Church, the title “pope” wasn’t yet in use, and the election was still conducted by locals. In 250, a week after the death of Anterus, the local Christian community gathered to vote, and there were several papabili among them, but, according to Eusebius of Caesaria:

Fabianus, although present, was in the mind of none. But they relate that suddenly a dove flying down lighted on his head, resembling the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Saviour in the form of a dove. Thereupon all the people, as if moved by one Divine Spirit, with all eagerness and unanimity cried out that he was worthy, and without delay they took him and placed him upon the episcopal seat.

Fabianus, whose life before this point was almost entirely unrecorded, thus became the first (and so far last) pope selected by pigeon (we can all agree that doves are basically glorified pigeons, right?). The symbolism of the Holy Ghost would of course appeal to a pious writer like Eusebius, so it seems churlish to point out that Rome had a long and entirely pagan tradition of seeking divine knowledge from the behavior of birds.

2. Boniface I/Eulalius, 418: Let’s Just Brawl This Out

By the fifth century, the Roman Empire was officially Christian and the church was an important political player, and people weren’t going to rely on the whims of birds to pick the most important Western churchman. When Pope Zosimus died, there were two rival factions within the local clergy — the deacons on one side and the priests on the other. The deacons occupied the Lateran and elected their leader, Eulalius, pope; the priests set up camp in a church in the western part of the city and elected Boniface, supposedly against his will.

Eulalius insisted on busting into town and celebrating Easter mass anyway, which set off more riots and ended up getting him arrested.

Several days of street brawls between the two popes’ followers ensued, until Symmachus, the city of Rome’s administrator, who was in his first week on the job, decided that Eulalius was the rightful pope (he had been elected first, by a day), and ordered Boniface kicked out of the city. But Boniface’s people managed to appeal to the emperor Honorius, who agreed to mediate in the dispute and ordered both candidates to stay out of Rome until the whole thing was settled. Eulalius insisted on busting into town and celebrating Easter mass anyway, which set off more riots and ended up getting him arrested. Honorius canceled the church council that was going to rule on the question and just told Boniface he was pope now, because Eulalius had been such a jerk about everything. According to the moderately sketchy Liber Pontificalis, when Boniface died a few years later, the Roman clergy asked Eulalius if maybe he wanted to be pope for real this time, but he told them to stuff it.

3. Benedict X/Nicholas II, 1059: The War Of The Would-Be Popes

After the collapse of the Roman Empire, the papacy went through some rough times, during which elections were controlled by regional nobles, who often arranged for their teenage relatives/bastard children to become pope. The low point came during a stretch of the 10th century charmingly referred to as the “pornocracy” because of the popes’ sexual relations with various powerful noblewomen.

But by the 11th century, things seemed slightly improved. In 1059 Giovanni Mincius was elected pope, taking the name Benedict X. Sure, Giovanni was relative of the Count of Tusculum, the local big shot, but he was a considered a reformer! Unfortunately, the previous pope had made the Roman people swear an oath that they wouldn’t elect a new pope until Cardinal Hildebrand, the reformers’ ringleader, returned from a trip to Germany, an oath everyone was happy to forget when plied with Benedict’s family’s money. A good chunk of the cardinals left the city in a huff, met up with Hildebrand in Siena a few months later, and elected Gérard de Bourgogne, who took the name Nicholas II. Nicholas and his crew then proceeded to make actual war against Benedict’s supporters, which the former eventually won, and Benedict was thrown in jail and died there twenty years later.

In the aftermath of this unpleasantness, Nicholas promulgated the papal bull In nomine domini, which established that the cardinal-bishops are the ones who elect the pope. This theoretically cut the easily bribed lower clergy and Roman people out of the equation, and thus ensured that future elections would be based on sober consensus about what was best for the Church and its mission of spreading Christ’s good news. (Spoiler: This didn’t happen.)

4. Gregory X, 1268–1271: The One Where They Removed The Roof

That’s not a typo: this election took three years to pick a pope. The cardinals were meeting in Viterbo, a hill town outside of Rome, and were divided into four factions — a group of Frenchmen and three mutually hostile groups of Italians — with nobody willing to give.

In late 1269, after several months during which the cardinals met only occasionally, the city magistrates rounded up them up and locked them in the papal residence there.

In late 1269, after several months during which the cardinals met only occasionally, the city magistrates rounded up them up and locked them in the papal residence there. In the summer of 1270, Cardinal John of Toledo, seeing one of his fellows praying for inspiration, quipped, “Let us uncover the room, else the Holy Ghost will never get at us”; getting wind of this, the city magistrates arranged for the roof of the meeting hall to be ripped off, exposing everybody to the elements. And yet: still no pope. The food sent into the palace was cut back to bread and water. Still no pope.

Finally, under pressure from the kings of France and Naples, the cardinals agreed to delegate decision-making power to six from among their own number — a mechanism not unlike the Congressional supercommittee that was supposed to stave of the current budget sequester. Shockingly, the dysfunctional papal conclave proved less dysfunctional than the U.S. Congress, and on November 1, 1271, the cardinals compromised and picked Teobaldo Visconti, a bishop who was off in the Holy Land with a crusading army. Visconti, who took the name Gregory X, finally reached Rome in March. Although the idea of locking the cardinals up had been a spur-of-the-moment expression of frustration on the part of the Viterban leaders, Gregory thought it was a great idea (it had, after all, resulted in his election). He promulgated the bull Ubi periculum that ordered all future elections to take place under similar circumstances, with the cardinals to be locked up cum clave, i.e. “with a key,” thus creating the institution of the papal conclave more or less as we have it today.

5. 1378, Urban VI/Clement VII: And Later, The Cardinals Went Into Hiding

There was a reason the popes spent a lot of time in little Italian towns like Viterbo: Rome, which was theoretically the capital of an Italian principality that the popes ruled, was a chaotic, ungovernable mess. In 1305, the cardinals had elected the Archbishop of Bordeaux as pope, and he decided to not bother going to Rome at all, but instead settled down in the southern French town of Avignon, because it was much more manageable and more convenient in terms of getting advice from his close personal friend the King of France. He summoned the church administrators to meet him there, and he and his successors stayed there for the next 70 years.

This grew increasingly appalling to Christendom at large and rulers who weren’t the King of France in particular; finally, in 1377, Pope Gregory XI was wooed back to Rome, in part by the stirring oratory of St. Catherine of Siena and in part to look after his political interests there. After a little more than a year, Gregory decided that, nope, the place was still a shithole, but he dropped dead before he could go back to France. In the midst of a violent thunderstorm and an equally violent mob that kept breaking into St. Peter’s and shouting, “Romano lo volemo, o al manco Italiano” (“We want a Roman, or at least an Italian,” and that actually scans sort of like “The people united will never be defeated,” so just imagine it sounded like that), the cardinals took just a day to pick Bartolomeo Prignano, who would take the name Urban VI. Prignano was not actually present, and the Roman mob thronged around the aged Cardinal Tebaldeschi, mistakenly thinking that he was the new pope, while the rest of the cardinals fled deeper into the papal palace and barricaded themselves in their quarters.

It was not hard to argue that this election had taken place under duress, and when Urban started preaching that cardinals needed to stop living in luxury and accepting salaries from various princes, most of them left town. Five months after electing Urban, they declared the papacy vacant and elected a French cardinal as a rival pope who promptly moved back to Avignon. There would be multiple mutually hostile popes for the next forty years. It was super awkward.

6. Pius VII, 1799–1800: France Spoils Things… Again

In the late 1700s, armies of the French Revolution conquered Northern Italy. By 1797 some of the revolution’s more radical anti-Catholic moves, like the attempt to turn Notre Dame Cathedral into a temple to the Cult of the Supreme Being, had flopped, but France and the church still weren’t exactly on good terms. In 1797, a general at the French ambassador’s residence in Rome tried to get a republican rally going and was shot by papal troops, which was all the excuse the French needed to invade Rome and declare it a republic, then arrest the pope and bring him back to France, where he died in custody in August of 1799.

The popes would end up using this tiara for decades because it was actually light enough to wear comfortably.

The city with the most resident cardinals outside of French control was Venice (itself under occupation by the pro-Catholic Austrians), so the fugitive church gathered there, in a monastery on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. In the face of the church’s greatest crisis in centuries, the cardinals naturally bickered for four months before finally settling on Barnaba Chiaramonti, who took the name Pius VII. With all the papal headgear having been plundered by the French army occupying Rome, Pius had to settle for a paper-mache tiara for his coronation, made in haste by the ladies of Venice and decorated with their jewels. The popes would end up using this tiara for decades because it was actually light enough to wear comfortably. Within a year, Pius had signed a treaty with Napoleon and was comfortably back in Rome and all was well that ended well, except for the part where his predecessor died in prison.

7. Pius X, 1903: “No, No, Take This Letter”

From the 1600s on, the heavy hitters of the Catholic world — the kings of France and Spain and the rulers of Austria — had occasionally exercised the right to veto candidates for pope, by telling cardinals from their realms which potential popes were unacceptable; this information would be announced to the other cardinals if it looked like the unfavored individual were about to be elected. But the practice had gradually fallen out of favor, and the last time it had been successfully used to block an election had been 1831. (The Austrians had attempted to veto the election of Pius IX in 1849, but the cardinal who had been assigned the task arrived at the conclave too late to prevent it.)

By the turn of the 20th century nobody in the College of Cardinals had given much thought to this presumably extinct institution. Nevertheless, Jan Puzyna de Kosielsko, a Polish cardinal from what was then part of Austria-Hungary, arrived at the 1904 conclave with a formal letter from Emperor Franz Joseph excluding the liberal Mariano Rampolla from consideration; after a day of voting in which Rampolla ended up in first place but short of the necessary two-thirds majority, Puzyna attempted to hand the note first to the dean of the College of Cardinals and then to the secretary of the conclave. Both of them refused to even touch it, so Puzyna ended up just reading it aloud. Everyone present reacted with horror and disgust and declared that the church could not possibly be bound by any sort of secular mandate, and yet Rampolla’s support rapidly melted away and the cardinals ended up electing a conservative a few days later. Despite the fact that the veto was responsible for his election, one of Pius X’s first acts as pope was declare that anyone who attempted to bring a veto into the conclave would be automatically excommunicated.

You might also enjoy: Roman Emperors, Up To AD 476 And Not Including Usurpers, In Order Of How Hardcore Their Deaths Were

Next week, Josh Fruhlinger wll be watching one of the no doubt many Vatican webcams, looking for white smoke. Follow him on Twitter or Tumblr. Photo of 1998 Cadillac “Popemobile” by the Hartford Guy.