Internet Parodist Does Incredible Job Of Imitating Yale Community's Sense Of Entitlement, Self...

Internet Parodist Does Incredible Job Of Imitating Yale Community’s Sense Of Entitlement, Self-Importance

Brave Heroes Denied $1.3 Million Reward For Finding Killer Cop

When the ex-LAPD supervillain Christopher Dorner rampaged across Southern California last month, Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa announced a million-dollar reward for information leading to Dorner’s capture. Three brave heroes who survived their encounters with Dorner have since claimed the reward, but the stingy governments and groups who offered the money now refuse to pay because Dorner somehow didn’t survive an army of cops roasting and demolishing the mountain cabin he holed up inside for his last stand.

Jim and Karen Reynolds survived a real-life crappy thriller movie when Dorner tied them up and held them prisoner in their nearby vacation cabin, and Rick Heltebrake lived through a harrowing carjacking by Dorner. Now the so-called community leaders who offered the reward are saying, “Ehh, Dorner didn’t actually make it to being convicted, so maybe we’ll just keep this money.”

A lawyer working for the Reynolds couple says local governments cannot get out of paying the reward just because Dorner died in the battle. “California law Penal Code 1547E states that local government is authorized to issue rewards that are paid on the capture and/or conviction of the suspect, and if the suspect dies, in the course of a police dispute or while in police custody then the requirement that he be convicted is eliminated,” attorney Kirk Hallam told ABC News in Los Angeles.

There’s a law for this because California cops are all crazy war veterans and cyborgs, and pretty much any Wanted Suspect ends up full of bullets, or burnt down to a skeleton, or exploded.

Please Stop Talking About Jon Hamm's Enormous Penis

“I’m wearing pants, for fuck’s sake. Lay off. I mean, it’s not like I’m a fucking lead miner. There are harder jobs in the world. But when people feel the freedom to create Tumblr accounts about my cock, I feel like that wasn’t part of the deal…”

— I would like to see Jon Hamm’s contract just to verify this.

Someone Still Having Fantasies About Steven Seagal

“A Lost in Showbiz article about the actor Steven Seagal was removed from our website because it was based on a magazine article which was intended as fantasy (What would it take for California voters to back Steven Seagal all the way to the Senate? Exactly the right length of ponytail, apparently, 22 March, page 2, G2).”

Deke Richards, 1944-2013

Deke Richards, 1944–2013

Motown songwriter Deke Richards died of esophageal cancer on Sunday in a hospice in Bellingham, Washington. Born Dennis Lussier in Los Angeles, Richards and his partners in the songwriting collective The Corporation — Alphonso Mizell, Freddie Perren and Motown founder Berry Gordy — wrote and produced the songs that made the Jackson 5 famous. Starting in 1969, the first three singles the band released on Gordy’s label — “I Want You Back,” “ABC” and “The Love You Save” — all hit no. 1 on the Billboard charts. The year before, though, Richards was part of the team (called “The Clan”; those guys chose some really bad names for their songwriting collectives) who wrote “Love Child,” also a no. 1 hit, for Diana Ross and the Supremes. For some reason, “Love Child” (above) is one of the songs I have the strongest memory of hearing in the first few years of my life. My mom must have played that one a lot. She was sort of a hippie, and surely appreciated the socially conscious message of the lyrics. Or, jeez, now that I think about it, maybe I’m a bastard?

Plates Small

There is a great struggle that is tearing our nation apart, turning brother against brother, cousin against cousin, person with expense account against person who has meticulously planned out what she will order before she has left work even though she knows no matter how careful she is she is still going to end up on the hook for another thirty bucks she did not account for etc.: It’s the war against entrees. What side do you come down on in this titanic conflict? Tell us in the comments!

The Things To Do Are Numerous!

It’s actually a hot evening in New York City, one of those nights when this ol’ town deserves its reputation for being awesome. See what I mean?

Game of Crones: A Chat About Jane Campion's "Top Of The Lake" So Far

by Jane Hu and Michelle Dean

Jane: Wow, so the third episode of Jane Campion’s seven-part series, “Top of the Lake,” aired last night and it wasn’t until I started reading reviews that I realized how divisive Campion can be. Granted, this is her first television venture to be released in the U.S., and perhaps viewers are more used to Campion’s lush aesthetic on big screen, but it’s not like exaggerated dramatics are unknown quantities in TV-land either.

So I know we’re both Campion enthusiasts (Bright Star, would other films be steadfast as thou art?!), and while I’m absolutely loving “Top of the Lake,” there are definitely moments that leave me puzzled. Though we’ve only seen the first three episodes (and warning: this conversation will include spoilers for those), I’m anticipating many more plot-twists to come. But to back up — the show is somewhere between a thriller and police procedural. Campion and her reviewers have compared it to “The Killing,” but “Top of the Lake” veers from the typical “who murdered the dead girl?” narrative by 1) introducing us to the girl as alive; 2) introducing the core dilemma not as who killed, but who impregnated, the girl; and 3) making the girl not white. The young heroine, Tui Mitcham (Jaqueline Joe), is 12 years old, and she’s the first character we see in the pilot. Let’s start with her! What did you think?

Michelle: Ugh, the reviews. First, I do not understand why people are acting like Campion’s been underground since The Piano. It simply isn’t true. Holy Smoke, In the Cut, Bright Star — I mean, I realize these are all films about women and that maybe then not as many people watched them but it’s sort of weird to enthusiastically broadcast that. She’s not been in a cave for twenty years. Then there are pieces like the one by Mike Hale , which seem to get no farther than a “Chicks, man” critical stance. How dare Campion be obsessed by gender politics! askdakflljgh

Anyway, onwards: Tui struck me, in her brief appearances, as one of the more recognizable 12-year-olds I’ve ever seen on television, sullen and defiant and smart, no wise-cracking, just wariness. Given that we learn very quickly that she is pregnant, some of her guardedness seems related to that at first but I suspect it’s more of a personality trait than that. It’s not clear that we’re going to see that much more of her but her instincts — the way she doesn’t seem particularly afraid of her abusive father, Matt, just coolly reaching for a shotgun to ward him off — are something beyond the delicacy and fragility that plague depictions of young dead girls.

Jane: Usually, the dead girl in such shows is, being dead, more symbolic than active (this is why is why I love the hallucinatory portrayals of Alison in “Pretty Little Liars” so much), which made Tui appear all the more striking on screen. Her interactions with others are electric because she is, as you mention, hostile and enigmatic, and very much alive. She’s also unpredictable, to the viewer (I really wasn’t sure at first where that shotgun scene was going) and to those around her, such as Robin Griffin (Elisabeth Moss), the detective who’s made it her goal to help her.

Michelle: I looked up Tui’s name and it turns out it means something like “wandering bird” in Thai. Which fits, as she’s gone by the end of the first episode. That Tui is a “gone girl” who isn’t white may slip by a lot of viewers without notice, but it’s the first signal that this will not be like every other violence-against-women police procedural I can think of (certain seasons of “Dexter” excepted).

Jane: As someone alert to bodies that aren’t white on television, Tui stuck out immediately, and she might have even stuck out as almost unbelievable (the mystical other!) if Campion hadn’t created such a realized and lived-in world in her isolated New Zealand community.

Michelle: Being not-American, as you and I and Campion all are, it seems important to bring up the particular position that Thai immigrants in New Zealand, like Tui’s mother, are in. I did some digging, sensing something awry with Tui’s mother’s situation. (She seems to be living in the back of a store with Matt’s son Johnno, i.e. Tui’s half-brother.) It turns out that there is a concern, in New Zealand, that many Thai women immigrants are victims of human trafficking, sometimes escapees from the sex trade in Bangkok itself. (Please understand I’m not saying this means all Thai women in New Zealand are present or former sex workers, only that it’s an idea that is in the public consciousness “down there.”) Campion is not the kind of person to sidestep things like that, though I suppose it’s possible it’s a red herring.

Jane: Absolutely, which is why it feels odd that reviewers are so quick to read “Top of the Lake” as allegorical — innocent children and damaged women against evil men! — while evading questions of geography, race, and political climate. Red herring or not, Robin’s scene with Tui’s mother was suggestive on a number of levels, from the corner store at which she works, to the fact that Johnno has to translate between them. As in this instance, the outsider status of Robin is emphasized throughout, but she’s also the audience’s point of identification, leading to all sorts of uneasy scenes.

Instead of framing it as Women, Good and Men, Bad, it makes more sense to see these characters as Outsiders, Different and Locals, Same. The group women living on the plot of named “Paradise” (led by a flowing grey-locked Holly Hunter as “G.J.”) are not only unassimilated to this specific NJ community, but they’re also unassimilated from one another. These women live in shipping containers (talk about migrants) in a sort of camp-out arrangement, and Campion shows them constantly in contention with one another, even if at the level of an eye-roll. Against this are the men of the town (all of whom I can distinctly tell apart, unlike those of so many American network and cable dramas) who are uniformly afraid of change to their, yes, sexist lives. (“Is she a she?” they keep asking, about G.J.) I don’t read these character as clichés, though, because they’re utterly believable. G.J. and her crones, in all their resentment and vulnerability, are so compelling. And they didn’t look like any other television bodies. (Drive-by old lady nudist really brought that home, like a reminder of “I’m here! I exist!” always in the background.)

Michelle: Yeah. To me the drive-by nudist is just one of the show’s many giant middle-fingers to the world. Another one, in the Game of Crones (I’m sorry) is that when Matt arrives to find the occupants of Paradise already setting up, one of the women tells him a whole song and dance about how her pet chimp died. She describes the chimp as though it were sort of an abusive boyfriend, and then says sadly she had to have him put down. It’s a weird story but I loved it; Campion is fucking with her audience, who like Matt expect these women to be crazy. (The scene is in fact so ambiguous I can’t tell if the woman herself is fucking with him, though she insists she really is talking about a chimp.) And in a way, they are, but it’s a kind of crazy born of a lifetime of bad experiences with men. One woman decides to take charge by driving to the local bar and offering them $100 for seven minutes in heaven, as it were, and when she explains why it has to be seven minutes, not six or eight, you kind of get it.

Jane: Yes! In the most recent episode, Matt returns to Paradise and tries to give her a bouquet of flowers while she’s sitting in a car, and she just looks in horror, rolls up her window, and drives away. NO ATTACHMENTS. Anything can become a point of attachment! Which also seems to be the underlying logic of the detective genre too — not just that everything can become a clue, but that romantic attachments are often obstructions (this is tweaked when you have a female protagonist, of course).

Michelle: I do think the power plays are pretty explicitly gendered; I agree there is “different” going on on top of them but so far there isn’t a single man on this show with unquestionable motives. That said, I’d be happy to hear someone tell me precisely what is so unrealistic about what Robin is seeing up by the lake. I don’t think I only know asshole men, that seems a bit much, but so far the dynamics of sexual assault, and even the police’s reaction to it, don’t seem to me to be so far off.

That said possibly the thing ringing falsest to me in the first couple of episodes is G.J. It’s either the wig or something else; she’s too… on point.

Jane: HOLLY HUNTER, WHAT IS HAPPENING? Campion, for me, is one of those directors that can move from subtle to being utterly on the nose, and I think Hunter’s character is currently leaning toward the latter. Is it her long, gray (barely-masked wig of) hair? Is it how she’s always smoking a cigarette? Maybe it’s the outfit and Hunter’s delivery that makes G.J. look like she just came out of a 1950s Western. She speaks in these seer-like aphorisms that aren’t just predictive, but sound almost like threats. Is she mystical, omniscient, telepathic? I don’t know whether to feel safe in her presence, or giggle (if a bit nervously).

Regardless, as we know from The Piano, Hunter has a magnetic attraction about her and in “Top of the Lake,” she’s again set against the most stunning backdrop. G.J.’s “Paradise” is set on a plot of land that justifies its name, but is described as a recovery home for “women in a lot of pain” (the name “Paradise” quickly turns from on the nose to, like drive-by nudist, another Campion “fuck you”). And even “Paradise” doesn’t quite belong to these women: Matt’s mother is buried there and, as became clear last night, he really wants it back.

Is this New Zealand story about a struggle over land, a fight for territory? On the ground, everything begins to resemble a Western, or frontier film, where small communities compete for survival and one fallen woman — or in this case, girl — represents futurity, however menacingly. From above, the panoramas of lush New Zealand mountains reminds me of Herzog’s Grizzly Man, which is set in Alaska on the other end of the planet (though we all know how that ended). There can be no generalizing about nature, and things are never as they seem. From The Piano, to those opening minutes of In the Cut, to almost every exquisite scene in Bright Star, Campion is a master of filming nature. Like Herzog, she makes nature uncanny. They’re like moving paintings, a Jeff Wall production, and I think the aestheticization — that is, the flattening — of New Zealand is something we should watch for.

Michelle: But in Campion’s films some people are of nature, and then other people are trying to subdue the wild. (In The Piano, the former is Harvey Keitel, the latter Sam Neill.) Tui, I think, is the former in this schematic. She walks into the lake. And when Tui comes over the mountain on horseback, headed to the compound at Paradise, weapon strapped to her back, it’s all… very Lone Ranger. Or rather Tonto, I guess. But something about her survivalist look there (as refracted through, I dunno, Tiger Beat) is meant to tell us something, make us believe that she could survive in the wilderness alone. She is of it, the wild.

Which is sort of funny because later in the second episode, when a policeman suggests exactly this, that Tui like an animal has crawled off into the wood to give birth somewhere, Robin dresses him down. And we feel she is one hundred percent right! I mean, really, what a ridiculous notion of human childbirth to adopt, one only available to someone who has never bothered to look into what women go through. But it’s one thing to elegantly link Tui to some idea of the natural, and another for it to be imposed on her by someone who hasn’t the faintest clue what he’s talking about.

But the analogy between Tui and animals keeps growing. In the third episode, she is suspected to be the body buried in a shallow grave on the property of a known child molester. But in fact, the Kiwi CSI team finds the corpse is a dog. And here again I felt, as a viewer, like Campion was trying to flip me off. Like: you think Tui would go that easily? You think she’d just accept her death gently, like a dog? How can this be the explanation? In another kind of show I’d be annoyed by the whole digression into Wolfgang, the child molester, who I think it’s pretty clear from the start is not the man we’re looking for. He is not the answer, this man living in such obvious suspicion in the creepy cabin in the woods. But I think it’s interesting the way Campion handles this. Like: of course it’s not him. Of course it isn’t.

Jane: Campion is an expert at the flip it and reverse it, and she uses the misdirection trope of detective narratives so well here. This is why I reject the notion that she’s heavy-handed; “Top of the Lake” hinges toward naturalizing, even animalizing, the women on the show, and then veers around to show them resisting such simplification. Campion’s shots can be seductively beautiful, but they’re also quite menacing — so when you place a group of half-broken women in half-open shipping containers in the middle of this landscape, they don’t map onto one another in any easy analogy. Instead, they’re unpredictable in a way that constantly threatens their so-called ecosystem, and you realize that the moments which brought them here are heavily cultural, political, patriarchal and bureaucratic, and they’re just looking for a place outside those histories and contexts.

Michelle: Speaking of threatening ecosystem, much of the foregoing we wrote before we saw the third episode, and we kept reading that the third episode would be a game-changer, and we wondered if we would have to rewrite all our conclusions in light of it. But I found it much more ambiguous. First we learned that there’s a drug lab belowground at the Mitcham place, which is no doubt what Mitcham wanted Tui to keep quiet about. But I think what was supposed to throw us off was the scene where Matt Mitcham, mid-ecstasy trip, takes one of the crones to his mother’s grave in the wilderness, tells her he’ll “fix this” and then kneels before it and whips himself with a belt.

The funny thing about the self-flogging is that I felt we were being played with again. There’s this odd attitude towards misogynists sometimes, that believes that if they managed to revere one woman it means they could not hate the rest of them. But in general, it seems to me, the hatred of women comes from starting out with some unattainable ideal of them. And a woman who wants you to “fix” things, one who inspires you to whip yourself with a belt, as Matt’s dead mother does: well, that’s Norman Bates stuff. That’s how misogyny works!

Jane: Right, and that’s what TV narratives do: they give you specific exceptions of love, marriage, something approximating equality among a man and a woman, and it’s supposed to lull you into acceptance… It feels like Campion might be just aggressively suspicious enough here not to let all the heterosexual dynamics resolve themselves so easily. We should note that “Top of the Lake” is, like The Piano, very much about mothers and maternity. I can’t help but read into Robin’s deflection of the question “Do you have children?” when caught looking lovingly at the video of Tui dancing (which is also a trope: “Twin Peaks,” “Pretty Little Liars”).

Michelle: That said, I guess the impotence sort of eliminates him as a suspect in Tui’s pregnancy. Though to be honest I suspect her slip of paper, the “no one” she says “did this to her,” is the truth. At the beginning of that first ep — blink and you’ll miss it — a boy on the bus sends that “r u ok?” text. He shows up again in her cell phone pictures. Is he wearing a blue hoodie? I feel like I’m afraid to double-check. I don’t want to figure something out too early.

Jane: Too late — I checked! And he is! He is wearing the blue hoodie!

Jane Hu is a writer; she does not own a blue hoodie. Michelle Dean writes in a lot of places, now. Follow her on Twitter.

New York City, March 25, 2013

★ Trash blew in a flat loop two or three feet off the ground, occasionally dipping to skim the pavement. Grit flew at the eyes. The snowflakes could be felt at the top of the subway steps several seconds before they came into focus. A little girl pulled her scarf up over her nose, then her eyes, leaning blindly into the woman she was walking with. The snow went over to a fine, unappealing rain, under summery-looking uneven gray clouds. A man in a fitted tan jacket walked under an umbrella, close beside a man in a fitted quilted blue jacket with water puddling on the shoulders. Down in the Columbus Circle station, the air was damp; a man played trumpet into a copper mute, with an irregular wet splotch on the platform where the spit valve had drained. The glow from the sky that fell on the rails of the 1 train was the color of mercury vapor lamplight.

What Happens After You Meet The Devil? The Life Of Mary MacLane

by Michelle Dean

Mary MacLane lived the dream, as we say nowadays. At least, in the beginning, she did. In Butte, Montana, where she grew up, she was just a bright girl in high school. She wanted to go to Stanford, but her stepfather spent the money that had been set aside for her education. She made the fields her world and wrote copiously in a notebook. What emerged was a long, piercing self-examination, about her frustrations with her family, as embodied by six toothbrushes (“Never does the pitiable, barren, contemptible, damnable, narrow Nothingness of my life in this house come upon me with so intense a force as when my eyes happen upon those six tooth-brushes.”). And the frustrations of feeling attracted to, you know, the Devil (“Think of living with the Devil in a bare little house, in the midst of green wetness and sweetness and yellow light — for days!”). She copied out the results and sent the manuscript to Chicago, where it landed in the slush pile of Stone & Company, on a Saturday in late April. The company’s reader, a woman named Lucy Monroe, adored it. By Thursday it was off to print; another couple of months and the book was selling quickly. Girls of the age MacLane had been, when she’d written the book — 19, just on the edge of the world — related to it particularly (there were reports it inspired some of them to suicide). And MacLane found herself a train to Chicago to meet the grand fate of a famous authoress, whatever it was.

It was 1902. She was 21. The figure of the New Woman, who so preoccupied James and Ibsen, was still only appearing by fits and starts in children’s literature. Alice had made it to Wonderland a few decades before MacLane was born, sure, and Jo March had long ago married her strange Professor Bhaer. But MacLane was more or less Dorothy Gale’s precise contemporary. Anne of Green Gables would not be around for another six years, Meg Murry of A Wrinkle in Time was more than a half-century away. I give you that bit of history because I don’t know who I would have been without reading those books a young girl. The world would be all sky, all sea, with the map I’ve followed well into my adult life only half-drawn (and I’m not being remotely hyperbolic). I can’t for one minute imagine what it would have been like to be my own cartographer.

All caveats about the reanimation of the dead aside, I think MacLane could hardly have known what she’d bargained for by publishing that first book. That it did not turn out as she’d hoped seems indisputable. In her last book, published in 1917, she declared: “I am Mary MacLane: of no importance to the wide bright world and dearly and damnably important to me.” She lived only 12 years after that, most of them in hiding from the world. And she’d never publish another book.

***

The sun of the wide, bright world has come to shine on MacLane again. Melville House has recently reprinted of two of her three books, I Await The Devil’s Coming, her first, and I, Mary MacLane, written when she was 34. (Her second book, My Friend Annabel Lee, originally published in 1903, remains out of print — and out of the conversation. Possibly because it’s written as an extended dialogue between MacLane and a “very pretty” porcelain figurine of a Japanese woman.) Reprints are occasions to make arguments for relevance, and to pique the interest of contemporary readers MacLane often has been presented as a sort of advocate for women generally and a great artist of the “female experience” (whatever that is). Yet it’s hard to imagine, once you read her books, that MacLane would have much appreciated the broadness of this argument. From the beginning, after all, MacLane openly resisted the idea that she was like everyone else, of her time or any other:

I wonder as I write this Portrayal if there will be one person to read it and see a thing that is mingled with every word. It is something that you must feel, that must fascinate you, the like of which you have never before met with.

It is the unparalleled individuality of me.

About Sylvia Plath, Janet Malcolm once observed, in her dry but shattering way, that, “We all invent ourselves, but some of us are more persuaded than others by the fiction that we are interesting.” There are many who would say the same of MacLane. Passages like the one here elicit uncomfortable feelings. One begins to feel like a party guest trapped by someone who lives in a state of Platonic irony, always saying the exact opposite of what she means. Or alternately, of being back in a prison of adolescent worries, the ones that fade rather than disappear altogether. Reading MacLane I felt less convinced that MacLane found herself interesting than that she was anxious to convey her high degree of interestingness to her readers, at any cost.

***

A bit more history: the first person to become enchanted with MacLane was that slushpile reader Lucy Monroe. In her mid 30s and unmarried, Monroe lived with her sister, Harriet. Harriet was still in the process of becoming that Harriet Monroe, a leading figure in modernist poetry, a woman who would in another decade found Poetry magazine and publish the early work of Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. It was with this pair that MacLane had been invited to stay in Chicago, after the publication of the book in a big imposing mansion of a townhouse on Astor Street, the likes of which did not really exist in turn-of-the-century Butte.

For some reason unknown now, the Monroe sisters did not meet her at the station. Instead, a phalanx of reporters did. She immediately told them, “I hate reporters, and I hate newspapers.” In return one reporter felt moved to remark, in his article, that she “is not pretty, is commonplace in dress and appearance,” and this despite the fact that she has arrived in some kind of “sailor hat.” Still, “once she speaks, she is decidedly original and startling.”

Here MacLane was already honing the talent she’d display in the coming months for giving the perfect quote. In a pre-soundbite age she already knew how to draw blood in one direct sentence. She knew to call Chicago “boring,” telling the reporters who helped her right into a cab that the enterprise looked like a “kidnapping, but I am not afraid, if I am alone in a cab with three men.” She could be blithe and funny, telling those erstwhile kidnappers, “I don’t know, we are all out for the dough.” But her sharp style of conversation formed the spine of every article about her.

To these same reporters, Lucy Monroe was soon complaining that their focus on quotes was a distortion of the essence of MacLane. “She is not at all the belligerent spirit she appears to be in interviews under the fire of pointed questions, which she feels she has to answer or be criticised for not answering,” Monroe told the Tribune. “Nor is she the severe critic she appears to the public. The interviews do not carry the pleasing personality, and the infectious laugh that comes when one is not looking for it.”

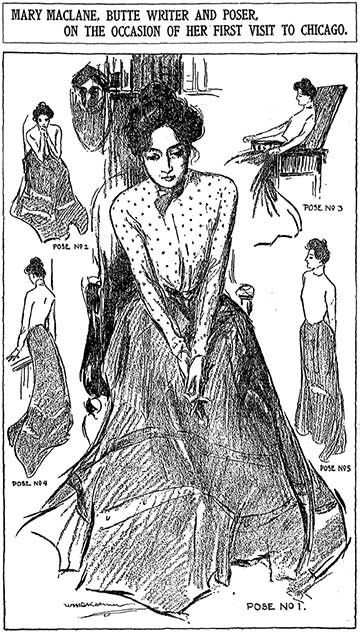

She was, in other words, posing. In fact, one of the first articles the Tribune ran about MacLane was accompanied by sketches of her adopting five different set poses. Each has a name: Meditation, Animation, Expectation, Illustration, Exaltation. The caption observes, “Her every attitude gives evidence of being well studied.” And yet: the pose called “Illustration” involves turning her back to the audience, the illustrating evidently being about showing something other than herself. “Exaltation” — standing tall, haughty look in eye — is defined as the attitude MacLane adopted when she was “inclined to defy the world and its opinion.”

They are all theatrics, all performance. That they are chosen and rehearsed and mediated and projected by the person doing them does not, necessarily, make them accurate representations of MacLane’s inner states of mind, merely what she wanted to project. And yet at the time, whenever reporters asked MacLane if her book was factually correct, if it told the truth, her answer was always the same. It was an “honest book.” To one, she said: “I could have written a book and made myself out a sweet, nice girl but I chose to tell the truth.”

***

Do we take MacLane’s word for it? Oughtn’t we to? In memoir, it’s sometimes said, the primary goal is emotional honesty. And in a way it seems the only person who can honestly (whoa) testify to their emotional truth would be the person herself, yes?

It’s always been a curious thing to me that many people consider “emotional honesty” a fixed and knowable quantity, when there are so many testimonies to “not knowing how I feel” about things. It goes back to Hamlet’s self-identified prison, the place where “there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.” And even dramatizing the thought process, which is arguably what stream-of-consciousness memoirs like MacLane’s do, is a certain kind of lie. Inner monologues are not inherently readable things. The readable things are narratives.

Malcolm (yes, back to her) once drew on a metaphor from Borges’ “The Aleph,” of being able to see everything on the planet from any angle, to describe the way narrative frustrates the truth: “How can one see all the ants on the planet when one is wearing the blinders of narrative?” This applies to more than insects, and even the post-modernists, the ones trying to represent the failures of narrative in stories themselves, still find themselves falling into the trap. The best ones are honest about that. David Foster Wallace himself once put it this way, in “Good Old Neon”: “What goes on inside is just too fast and huge and all interconnected for words to do more than barely sketch the outlines of at most one tiny little part of it at any given instant.”

My point is here is not that MacLane was dishonest, though. It is, instead, that we cannot possibly know what she was, and so predicating praise of her book on its “rawness” or “honesty” is to pretend that it is something other than a book, a pose, a performance, at best a half-truth about inner life. It gives her both too little and too much credit.

***

The critical reception to MacLane’s books was decidedly mixed. (It’s sometimes presented now as wholly negative, but it was more spiked than that, with some positive notices.) The most notable negative review came from a male critic in The New York Times who called it “ridiculous rot.” For her part, MacLane was always somewhat knowing about book reviews. As Kathryne Beth Tovo remarks in an unpublished dissertationon MacLane, MacLane actually wrote to her publisher that she wanted the book to get a negative review from a popular critical periodical like The Bookman, which would send it out “on a career of sorts.”

One part of the myth-making that surrounds MacLane’s career derailment is to remark that even H.L. Mencken mocked her. But his alleged denunciation, read now, is not so vehement. In the review, which appears in his collection Prejudices, he diagnosed her as “an absolutely typical American of the transition stage between Christian Endeavor and civilization,” caught between rigid religious laws and (his words) a “soaring soul.” Any self-dramatics, he pointed out, came from rigid Christian morals colliding with the ordinary acts of life, like kissing. While he was never much of a feminist himself, MacLane still somehow brought out a proto-women’s-libber in Mencken: “If it were not held universally in Butte that sex passion is the exclusive infirmity of the male, she would not blab out in meeting that — but here I get into forbidden waters and had better refer you to page 209.”

Here Mencken was writing about MacLane’s third book, I, Mary MacLane, published in 1917, which included some fulsome accounting of her adult sexual escapades. Apparently audiences did not find MacLane as captivating in her 30s. The public seemed uninterested in reports from the itinerant life of someone once-famous. In the time since the publication of My Friend Annabel Lee had garnered little critical response and fewer sales, MacLane had been floating back and forth between Massachusetts (where she could not persuade Radcliffe to admit her) and New York. Then for a long stretch following an illness from scarlet fever, she moved back in with her mother in Butte. She wrote newspaper pieces, but only intermittently. For most of the intervening time she was broke, borrowing money from friends like Lucy Monroe, harassing the publisher for back royalties.

Yet while I, Mary MacLane’s sales were bad, it still landed her a commission for a series of articles to the San Francisco Chronicle, and attracted enough renewed support that she got to make a movie, now lost to time, called The Men Who Loved Me. She wrote the screenplay and got to star in it. It was produced by a company that had once done the Chaplin films and now was in decline. In the end it opened to tepid reviews, and it’s not clear that MacLane ever saw any money from it.

From there things went bad to worst. First MacLane skipped out on a hotel bill in Chicago, which her friends later seem to have settled for her. Then she was charged with stealing her wardrobe from the set of The Men Who Loved Me. She began to lead an itinerant life in Chicago boarding houses. The Monroe sisters tried to keep an eye on her but it was of no use; MacLane, stubborn, stopped giving them her address. When she turned up dead in 1929, in one of those rooming houses, the cause was said to be tuberculosis, though the medical examiner listed it as “natural causes.” She had only been in regular contact with one friend, an African-American photographer who the press routinely mistook for her “maid,” who confirmed the tuberculosis.

Her death was widely announced in the press. In the classic MacLane pattern, every story told of her being forgotten in the lead paragraph below a headline that spelled out her name in enormous type. Even Publisher’s Weekly ran an obit.

***

Dying alone and unwanted in a cheap hotel is a particular kind of feminine nightmare. When I was going through the clippings for this piece I began to think, of course, of Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth. I often do, when I’m writing or thinking about what I’ve come to call the Weird Girls, the young women who, like MacLane, and the nature-obsessed diarist Opal Whiteley and the child novelist Barbara Newhall Follett, were different, and somehow concluded that their only option was to disappear. They fall right off the map.

It’s what Lily Bart says to Selden on her last visit to him that haunts me:

I have tried hard, and life is difficult, and I am a very useless person. I can hardly be said to have an independent existence. I was just a screw or a cog in the great machine I called life, and when I dropped out of it I found I was of no use anywhere else.

When Selden finds Lily dead, he finds her papers too, ordered bills and accounts, every debt paid. Which is how people found MacLane, in a way: the papers reported that her press clippings were strewn about her, though we’ll never know if that was a press embellishment designed to give the story a little bit of color.

As it happens, The House of Mirth was published in 1905, coming into the world just as things, after the first great success of Mary McLane, were beginning to come apart.

You might also enjoy: Becoming Joan Didion

Michelle Dean writes in a lot of places, now. Follow her on Twitter.