Manhattan Real Estate Explained, In Just One Street

by Brendan O’Connor

Manhattan’s 14th Street is never a pleasant place to be, but there are few streets that one can comfortably walk from end to end on a hot, late summer afternoon whereupon the full blossoming of capital is more radiantly displayed. There is an idea of New York, and especially of Manhattan, as a place where the wealthy and the less wealthy (and even the not-at-all wealthy!) live in close proximity, even adjacent, to each other, and that this arrangement produces ambition in the latter to attain what the former has, and some amount of respect for the humanity of the latter in the former. This is not just incidental to life here, the thinking goes, but integral to it: Everyone, or almost everyone, suffers the city together.

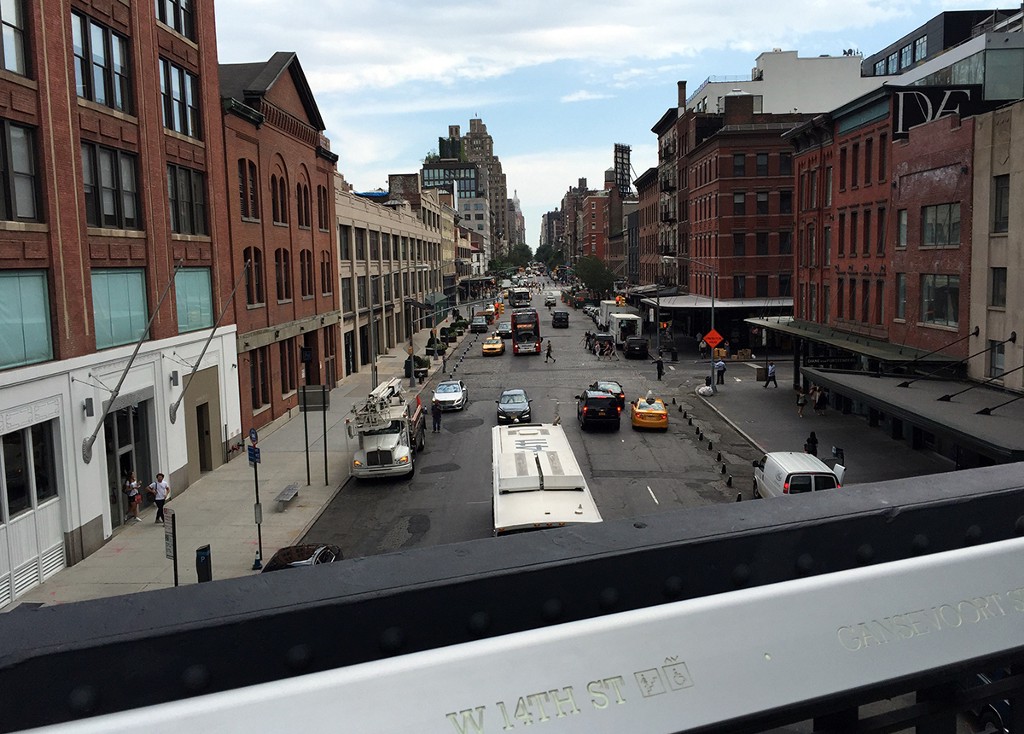

At least as far as most pedestrians are concerned, 14th Street’s westernmost terminus is the High Line, an elevated, linear park built on a disused, mile-and-a-half long section of the West Side Freight Line. There is a set of stairs up to the railroad track a few steps past an enormous Diane von Furstenberg store. Von Furstenberg, a high-end fashion designer, and her billionaire husband, Barry Diller, donated upwards of thirty-five million dollars towards the completion of the High Line. (Von Furstenberg and Diller have also pledged one hundred thirty million dollars to refurbish nearby Pier 54, in the Hudson River.)

The stretch of 14th Street between the High Line and 8th Avenue is heavily oriented towards retail, which is perhaps unsurprising, given that the High Line attracts at least five million visitors annually. (A smart investment on Von Furstenberg’s part, then!) But the High Line is a magnet for more than tourists’ money: According to a study conducted by the New York City Economic Development Corporation, before the park’s construction in 2003, the surrounding West Chelsea neighborhood — a mix of residential properties and light industrial businesses — were valued at eight percent below Manhattan’s overall median. In 2005, the city rezoned West Chelsea for luxury development, and, by 2011, residential property values appreciated beyond borough-wide values. “The park, which will eventually snake through more than twenty blocks, is destroying neighborhoods as it grows,” Jeremiah Moss wrote in the New York Times in 2012. “And it’s doing so by design. While the park began as a grass-roots endeavor — albeit a well-heeled one — it quickly became a tool for the Bloomberg administration’s creation of a new, upscale, corporatized stretch along the West Side.” Price per square foot for residential units within five minutes walking distance of the High Line more than doubled in less than a decade.

A random selection, from Streeteasy, of rental apartments in the High Line’s immediate area: a fourteen-thousand-dollar-a-month two-bedroom condo “on the cross road of Manhattan’s ultra stylish Meat Packing District, Chelsea and the West Village”; a thirty-three-hundred one-bedroom apartment with no broker fee; a twenty-seven-hundred-dollar-per-month one bedroom above Solstice Sunglasses. As one walks east along 14th Street, away from the High Line, out of the cobblestone and into the pavement, there are fewer high-end brands (DVF; Chanel; Fjallraven) and more shops whose wares seem more expensive than they should be, but not so expensive that you can’t not convince yourself that maybe they are somehow worth it: Kiehl’s, Patagonia, Levi’s. Also: Apple.

Eighth Avenue is the last stop on the L train, which rattles beneath 14th Street, intersecting with the A/C/E at Eighth Avenue, the F/M and 1/2/3 at Sixth Avenue, and the N/Q/R and 4/5/6 at Union Square. The Sixth Avenue subway station, which could really also be called the Seventh Avenue subway station, is matched only in its labyrinthine sprawl by the West Side Market just above. Between Eighth Avenue and Sixth Avenue is a hodgepodge of bars and bodegas; the Local 237 Teamsters union building sits across the street from a nail salon called “Yo Yo Spa.” Homeless folks sleep on the steps of the enormous Salvation Army executive headquarters. Rental apartments in the area are listed at essentially the same price range as a few blocks west: a three bedroom for twelve grand a month; a one bedroom for nearly thirty-eight hundred dollars; and a three-thousand-dollar one bedroom.

After Sixth Avenue, the buildings become taller and cleaner; there is more business attire. There are also students: Last year, construction was completed on the New School’s new University Center on Fifth Avenue, which, in the way of expanding college campuses, could have been terrible, but sort of isn’t, as these things go. (New York’s Justin Davidson praised the building for “balancing fresh needs with history” and retaining the New School’s “sensitive boldness.”) Still, the area does not feel like a campus, and caters more to its office workers. The average asking rent for Class A office space in the area reached eighty-three dollars per square foot this spring, the Villager reported in May. According to the Wall Street Journal, in 2011 the average asking rent in the immediate area was forty-six dollars per square foot. The rise has been driven largely by start-up and tech tenants like Yelp, which added ten-and-a-half thousand square feet to its Fifth Avenue headquarters last year. Also headquartered on Fifth Avenue is Compass, a “technology-driven real estate platform,” which last year began subletting office space (paying in the mid-sixties per square foot, the Real Deal reported).

Union Square is not 14th Street’s geographic center, but it is its center of gravity. On its worst days it is only slightly less chaotic than Times Square, thirty blocks north, but even then the chaos is more purposeful, or at least bounded: This is where the skaters and bikers are; this is where the street vendors selling African black soap are; this is where the Whole Foods shoppers skip past everyone else. In the mornings, the subway station below is a melee, but, as everyone knows where they are and where they need to be and how to get there, it is a navigable one. In the afternoons, there are often fewer people, but they are also less familiar with the space, and do not know how to get anywhere, disrupting the flow of bodies.

The blocks between Union Square and First Avenue are sort of a lost space — a friend once referred to the Third Avenue L station as “the most useless subway stop in New York.” (It and and the First Avenue station are the only two in Manhattan that do not intersect with a north-south subway line.) Here there are bars, hospitals, and more expensive apartments: fifty-five hundred for a two bedroom; five grand for a three bedroom; thirty-two fifty for a two bedroom. After First Avenue, there are three long blocks without a subway station, and then the street ends. To the north of these three blocks is the southern edge of Peter Cooper Village-Stuyvesant Town, an enormous planned community ushered into existence by Robert Moses, where, according to Streeteasy, the average asking rent for a one bedroom is more than thirty-five hundred dollars. To the south is Alphabet City, the easternmost section of the East Village, a now thoroughly-gentrified neighborhood — two new buildings, bizarrely, have been marketed under pop star’s names, The Robyn and The Adele — that is also home the city’s highest concentration of bars.)

This stretch of 14th Street, after the last subway station and before, at the edge of the East river, the Consolidated Edison power plant, is usually quiet. “It feels a little slow-paced — it almost feels like Brooklyn in a way,” one developer working in the area, Steve Ferguson told the Journal, in February. It does not, at all, but what’s more Brooklyn than plopping a big luxury development into a slow-paced neighborhood? Indeed, a huge swath of land — eight parcels! — between Avenues A and B were bought up and is being redeveloped into an enormous luxury mixed-use behemoth, EV Grieve reported in 2013. (This is what it’s going to look like, apparently.) Construction is due to be completed in January 2017.

Meanwhile, even further east, on the corner of Avenue D, at 644 East 14th Street, just across the street from Con Ed, the city’s electric heart, an empty lot awaits construction. A mixed-use building permit application was filed last year and approved in January: the development will total almost sixty-two thousand square feet, with nearly eight thousand, six hundred square feet of commercial space on the ground floor. Signage on the green walls around the lot indicates that building was supposed to have been completed this summer, but, peering through the holes in the walls, the ground does not seem to have yet been broken, even as posters advertise retailers like Theory, Coach, and Acne Studios. As it happens, Coach threw a party on the High Line earlier this summer — attended, naturally, by Diane von Furstenberg. And so now we have the promise of a New York that no longer festoons its capitalist mythologies with promises of social mobility but rather a place where rich people can sell things to each other, and sometimes to slightly less rich people, without having to worry about too much else at all.

Rendering of forthcoming 14th Street development by RFK